One of this country's most esteemed writers begins her first visit to Mississippi in Pass Christian, where she's met by many admirers of her work.

- story by Scott Naugle, photos by Ellis Anderson

As we spoke, in the distance behind her was the Pass Christian harbor and beyond that the expansiveness of the Gulf of Mexico, flat calm on the surface, mirror-like, an endless sea of possibilities. The breeze was warming, persistent.

Over her shoulder, several Sage bushes were in full bloom, flowering purple, deeply hued, and resilient to drought. To my eye, Oates was partially framed in purple, the color of magic and mystery. Virginia Woolf famously preferred to write with purple ink. Oates speaks carefully, fully considering each word. She’s pleasant and gracious. Her eyebrows slightly arch and the corners of her mouth move upward almost imperceptibly in response to a humorous aside. Small and lithe, Oates’ agility belies her eighty plus years. Her most recent collection of short fiction, “Beautiful Days: Stories,” was published in April to a chorus of positive reviews. In the second story in the collection, “Big Burnt,” two lovers are in peril, both physically and psychologically. After a day picnic on an uninhabited island, they are overcome in a ferocious thunderstorm while returning to the mainland in a small rented watercraft. “Directly overhead were flashes of lightning, vertical, terrifying, so close that the deafening thunder claps came almost instantaneously and she could not keep from whimpering aloud.”

Pass Christian Books has a limited number of signed copies of Oates' new books, Beautiful Days and Night Gaunts.

Much more than a story about a perilous boat trip, “Big Burnt” explores the mid-life desperation of a man and woman who have made compromises over the years and now question their choices.

If there is a recurring theme within “Beautiful Days: Stories,” it is the desperation of the human condition. When asked, Oates replied that the stories depict “psychological or domestic realism.” Through staging or setting in these stories, Oates reveals to the reader unvoiced nuances using physical details, step by step, creating interior spaces for the characters. As a story progresses, the carefully drawn details begin to suggest the psychological condition of a character. The details of the narrative, the pitch, the motions, all carry meaning within the story. “Ever more desperately she was bailing water. Like a frenzied automaton, bailing water…If she gave up she would crouch beside the man with shut eyes, pressing her hands over her ears, catatonic in terror,” continues the drama in “Big Burnt.” Earlier in the narrative, Oates described this character, Lisbeth Mueller,as, “Married too young, children at too young an age, two divorces, men who exploited her trusting nature, career missteps, misjudgments – how swiftly the years had gone.” Later in the story, the desperation of bailing water in a slowly sinking boat underscores with physical detail the perceived futility that Lisbeth has reached in her personal life, a life that may submerge and pull her under, “catatonic in terror.” Oates, among many other strengths, is a master of the subtext, seeding the reader’s imagination through micro-detailing of the physical environs.

It’s Saturday evening and Oates is preparing to read at the bookstore and coffeehouse in Pass Christian. While the expectation was that she may read from one of her two books released within the past few months, “Beautiful Days: Stories” or “Night Gaunts,” she instead reached for my copy of “Blonde,” published in 1999, a fictionalized re-imagining of the life of Marilyn Monroe.

Oates held the book delicately, carefully, as the work of art it is. Embarrassingly, my name was visibly on a blue sticker on the spine so as not to misplace the book among the hundred or more she signed that evening. With emotion and passion, she read, channeling Norma Jean Baker, the birth name of Monroe. As Oates held the book, attendees had a glimpse of a younger Oates on the rear dust jacket. Her deep, dark, sagacious eyes were unaged from the time of the photo, still searching, bright. Time appears to have not sullied her at all, the chin still firm and determined. Behind her, the Pass Christian Harbor and the area near shore where an experienced fisherman had drown several months ago, carried under by currents he did not anticipate.

There were many questions from the attendees. Afterward, she would remark to me that “all of the questions were intelligent.” Oates appeared to enjoy the interplay and dialogue with the admirers. She leaned toward them when responding.

From my vantage point beside her, en masse, as an organic unified body, the standing audience responded by leaning in to her with affection, respect, and gratitude for the work Oates has gifted them over the years. “I write from the heart, not the head,” Oates responded to a final question, unblinking, with the delicate lilt of a warming smile.

Editor's note: Fans of this column will note the absence of Carole McKellar, the avid reader and Bay resident who originated Bay Reads in the fall of 2014. She's relocated to Jackson. Although we miss Carole and husband/artist John McKellar greatly, we wish them well! We also wish to congratulate Jackson for its extreme good fortune.

However, we're proud to announce that Scott Naugle has taken the helm of the Bay Reads column. Scott is owner of Pass Christian Books, which sponsors this column and hosts many noteworthy literary events on the coast. He's also a seasoned writer, whose work has appeared in regional publications through the years. We're most excited to have him take on a greater role in the Shoofly Magazine!

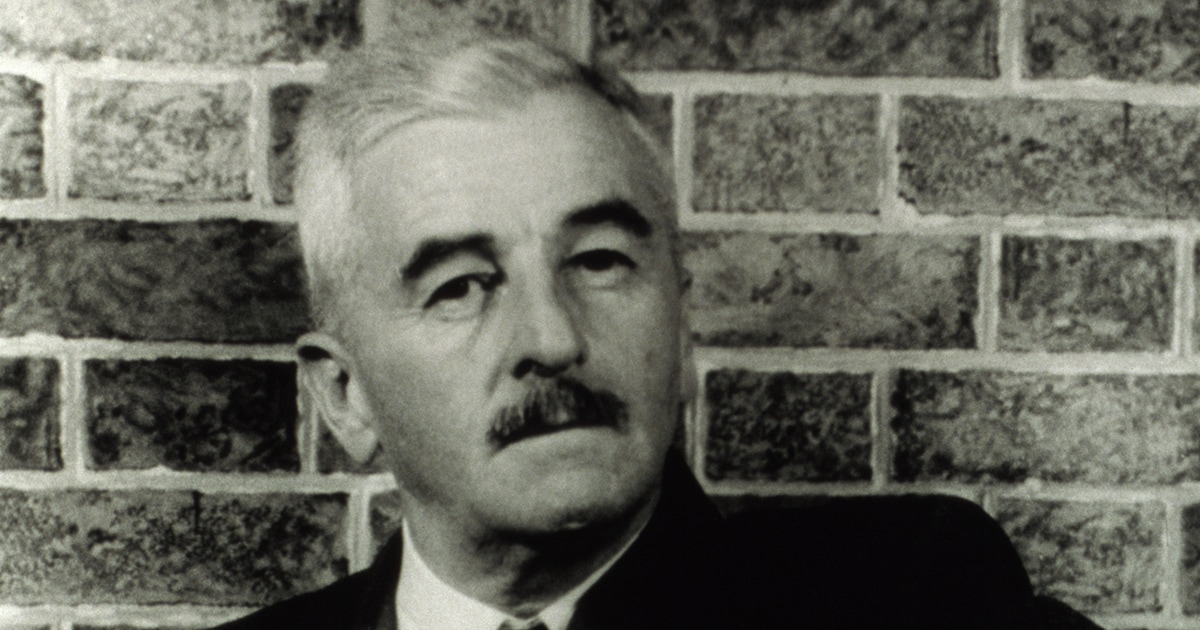

Writer Joyce Carol Oates, author of more than sixty books and one of the most esteemed living American writers, will be visiting the Mississippi coast in July, signing her two newest publications at Pass Books.

- by Carole McKellar

Born in 1938, Oates published her first book in 1962. She taught creative writing at Princeton University from 1978 until she retired in 2014. Oates has won awards for her writing, including the National Book Award for “them” in 1969, two O. Henry Awards, and the National Humanities Medal. Her novels and story collections were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize five times.

Beautiful Days, published this year, consists of eleven stories. All of the stories previously appeared in respected periodicals but never appeared together. The subject matter is diverse including stories of extramarital affairs and suicide alongside fantasy. “Les Beaux Jours” is about a vulnerable girl desperate for the love of her absent father. She is drawn into a Balthus painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The subject imagines herself a prisoner inside the painting and writes a letter to her father begging him to rescue her from the cruelties imposed by the Master. In “Undocumented Alien” a Nigerian student is saved from deportation by participating in a classified research project. A chip implanted in his brain adversely affects his cognitive function and drives him to madness. This chilling story describes a young man fighting to maintain his humanity. Although the eleven stories are disturbing and generally dark in tone, I liked this collection. Oates is a skilled and imaginative writer. Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense is on my nightstand, and I look forward to reading the six creepy tales within. The first story, “The Woman in the Window,” is a reimagining of Edward Hopper’s painting, ’11 A.M., 1926,’ which features a woman sitting in an apartment window naked except for high heels. That painting is on the front cover of “Beautiful Days.” At eighty years old, Joyce Carol Oates continues to earn the respect of readers and writers alike. She avoids celebrity and has cultivated a reputation for hard work and professionalism. Oates is regularly discussed as a strong contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature. I look forward to meeting Ms. Oates at Pass Books and consider it an honor for the coast to have such a literary icon visit.

Shoofly Magazine book columnist Carole McKellar checks out spellbinding new works by contemporary authors based on myths spun thousands of years ago.

I first turned to Edith Hamilton’s “Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes,” published in 1942. Hamilton’s retelling of stories from Greek, Roman, and Norse mythology is still used as an introductory text in high school and college. The sheer number of gods and goddesses outlined by Hamilton is overwhelming, but many names are embedded in our language: Zeus, Neptune, Aphrodite, and Atlas.

Greek mythology has provided inspiration to poets and artists from ancient times to the present day. Dating to the 8th century BC, Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey” are the oldest Greek writings available. Plato is probably the most famous Greek writer. His dialogues include the “Republic” and “Symposium.” Sophocles wrote 123 plays including “Oedipus the King” and “Antigone.” Only seven of Sophocles’ plays survived intact. The list of ancient Greek writers includes Aristophenes, Euripides, and Herodotus. Roman writers were heavily influenced by Greek literature. “Metamorphoses” by the Roman poet Ovid contains much of what we know about Greco-Roman mythology. Ovid’s writings influenced the works of Milton, Shakespeare, and Chaucer. Virgil, author of “The Aeneid,” is probably the most famous Roman poet.

Consideration of mythology is timely because of the recent popularity of books and movies about mythic heroes. Movies range from “Hercules,” a Disney animated film, to “The Hunger Games” trilogy from best-selling books by Suzanne Collins. “Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief” was based on the first novel in a Young Adult series by Rick Riordan.

My personal favorite is the movie “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” by Ethan and Joel Coen. This satire is based on Homer’s poem “The Odyssey.”. The film is set in Depression era Mississippi and tells of three convicts who undertake an epic journey to retrieve a treasure. The central character is Ulysses, the Latin variant of the name Odysseus, the hero of the epic poem. In addition to the Young Adult books, the list of books inspired by mythology is long and diverse. “American Gods” by Neil Gaiman weaves ancient myths into modern culture and was made into a television series. Margaret Atwood, famous Canadian author of “The Handmaid’s Tale,” wrote “The Penelopiad: The Myth of Penelope & Odysseus.” Madeline Miller, a Latin and Greek scholar, wrote “The Song of Achilles,” a novel about the Trojan War, and the newly published “Circe” about the goddess of magic and sorcery. Nashville writer Ann Patchett wrote about “Circe”: “An epic spanning thousands of years that’s also a keep-you-up-all-night page turner.” It’s currently on my nightstand, and I can’t wait to read it.

Mythical references abound in our culture. We’re all familiar with Nike footwear, named for the Greek goddess of victory, and the Apollo Theater, which gets its name from the Greek god of music.

Mardi Gras is filled with mythic names. Nereids, Muses, Hermes, Iris, Comus, Endymion are only a few named for Greek and Roman gods. Perhaps no Mardi Gras krewe is more aptly named than Bacchus, the god of wine and revelry. Other well known allusions to Greek and Roman mythology include:

It is a Herculean task to reduce Greek and Roman mythology to a few paragraphs, but even a cursory look points out its value to Western civilization.

A moving new novel by award-winning writer Minrose Gwin centers around the tragic Tupelo tornado of 1936. The Shoofly Magazine's book columnist Carole McKellar interviews the author and reviews the book.

Minrose Gwin will be at Pass Christian Books on Thursday, March 22 at 5:30 pm. She will talk about Promise and sign books. I hope to see you there, but, if you can’t attend, call the bookstore and have a copy signed for later pick up.

Although the characters are fictional, Gwin uses her intimate knowledge of Tupelo landmarks to provide readers with a vivid picture of the setting. Some places like the Lyric Theater and Reed’s department store remain in business today as they were in 1936. The Lyric Theater served as a makeshift hospital in the aftermath of the tornado.

The central characters are Dovey Grand’homme, an African-American laundress, her granddaughter, Dreama, and Jo McNabb, a white girl of sixteen. The McNabbs are a prominent Tupelo family, and Dovey does their laundry. She hates the family because Jo’s brother raped Dreama without punishment or legal consequences. Dreama became pregnant as a result of the rape and gave birth to a son named Promise. The characters in Promise are fully developed and complex. They display all too human emotions including guilt, hatred, and pride. I particularly liked Dovey who showed strength and resilience against a life of hardship. Jo and Dovey’s family are bound together by the horrific rape and their struggles after the storm. The events depicted take place between Palm Sunday, April 5, 1936 and the following Friday. The story is told alternately from the point of view of Dovey and Jo. After the storm, Dovey searched frantically for her family in the segregated makeshift facilities. She is eventually reunited with Dreama and her husband, Virgil, but they have to keep searching for Promise.

Jo’s story involves searching for her baby brother, Tommy. Jo's mother was seriously injured in the tornado and her father was not around. The two missing babies are at the heart of the story.

The depiction of destruction is drawn from actual photographs of Tupelo in the aftermath of the tornado. Gwin’s novel artfully creates an atmosphere and landscape that puts the reader on the broken streets with the characters and shares their suffering and despair. Her depth of research takes us to a lost time and culture. Minrose Gwin has a good ear for Southern phrasing and idiom. In that respect, she reminds me of Eudora Welty. I smiled when I read the phrase, “Katy bar the door” because my mother used that expression often when trouble was expected. I remember reading The Queen of Palmyra,* Gwin’s first novel, and thinking how true and familiar the characters felt to me. That book was also set in the Tupelo area. Minrose Gwin has been a writer all of her adult life. She began as a journalist, but found her calling as a teacher of English and creative writing at the college level. She most recently taught at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In addition to the two novels, she has written a memoir about her mother titled Wishing for Snow. In addition, Gwin wrote Remembering Medgar Evers about the slain civil rights leader who was murdered in 1963 outside his home in Jackson. I had the opportunity to ask Ms. Gwin a few questions which she kindly answered by email.

How long did it take you to write Promise? There must have been a lot of research that went into the story.

Promise really chose me. I was in the revision stages of another novel, when I learned that the stories I'd heard all my life about the tornado weren't complete--that the casualty figures weren't complete because members of the African-American community of Tupelo hadn't been included. This angered me and spurred me to write the novel, which I hope excavates the deeper devastation of racial injustice. Counting research, it took about 18 months. Since I grew up in this town, the landscape was the easy part. It was the fastest book I've ever written. Both The Queen of Palmyra and Promise deal with racism and its history in our state. You also wrote Remembering Medgar Evers. What influences led you to write about race in this way? Yes, race is a topic I've dealt with in my scholarly work as well as my fiction and memoir, from the very beginning. I am interested in history and how history shapes us, but my books, unfortunately, are as much about the present as they are about the past. I am white, but I was fortunate to have an African-American babysitter named Eva Lee Miller and to stay with her for extended periods in her home. During my formative years, I got to know her friends and family, their struggles, from inside her home, and I got the benefit of her considerable wisdom and saw the incredible power of her resistance to the racism that embedded the culture, and of course still does. We were in close touch until her death. She was and is a major influence in my life and writing. Did you hesitate to write in the voice of Dovey given the political climate today? By that I mean criticism of men writing in the voice of women or whites writing as African-Americans. I don't use the first person voice for black characters in The Queen of Palmyra or Promise. In the first book, the narrator is a white woman recalling the summer she was almost eleven, and in the second, there's an omniscient narrator relating the story from the alternative points of view of Dovey, the African-American great-grandmother, and Jo, the white girl. So we get the voices of the black characters through a filter. To my knowledge, no one has objected to that in my fiction. In writing both of these novels, I was trying to directly confront the social justice issues that remain with us today. I read about your memoir, Wishing for Snow, about your mother, a poet. Do you write poetry? Who are your favorite poets? There was a period in my life I wrote poems and a few were published. I've been told that my prose is poetic so there must be some link there. My favorite poets? Among contemporary poets, my favorites are Joy Harjo and Natasha Trethewey. I've always loved Keats, Stevens, and Dunne. How has your career as a journalist influenced your writing? My few years as a journalist were pivotal in so many ways. They acquainted me with tragedy. They taught me to get the words down on paper (now computer screen), even if they weren't perfect. Journalism taught me to check my facts. I like fiction that's grounded in facts--the Tupelo tornado in 1936, for instance, in the case of Promise. I like to get details right, like what blooms when and where, like historical detail. Journalism taught me to observe the world closely. Do you write every day? Writing every day is especially important when I'm writing a first draft because you have a certain momentum you have to keep up, a certain drive. What writers influenced you? I love Mississippi writers! I'm a Faulkner scholar, so he's been a big influence, also Welty, especially the visual in her work. I love her photography too. There's a photo she took of a laundress back in the 1930s that made me start shaping the character of Dovey in Promise. I've read all of Toni Morrison's work, and taught most of it, so she's been an important influence too. *Bay St. Louis residents will be interested to know that a portion of The Queen of Palmyra was written in the Webb School owned by Ellis Anderson and Larry Jaubert. Gwin was working in New Orleans at the time and used Webb School as a writing getaway.

Limited on time, but love a good read? Shoofly Magazine book reviewer Carole McKellar lists her favorite 2017 books - and gives "best of" lists from the New York Times, Publisher's Weekly and the Boston Globe.

— Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders was my favorite book this year. Saunders is famous for his stories, but his first novel won the Man Booker Prize. This novel takes place in the graveyard housing Abraham Lincoln’s beloved eleven year old son, Willie. Souls trapped in purgatory, called the bardo in Tibet, view Lincoln visiting his young son and find hope for their own salvation. Funny, dark, and totally original, this book will always have a place on my shelf of favorites.

— News of the World by Paulette Jiles describes the journey of a hardened veteran of multiple wars and a child captured and raised by a Kiowa tribe. The child remembers nothing of her life wearing dresses or speaking English. The love and trust that develops between them during their arduous trek across the lawless post-Civil War West brought tears to my eyes. — Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout is set in the small Illinois town that was the hometown of Lucy Barton, whom we first met in Strout’s previous book, My Name is Lucy Barton. Strout is one of my favorite writers, and this novel doesn’t disappoint.

— Moonglow by Michael Chabon is a fictionalized account of the life of Chabon’s grandfather, an adventurous scientist, engineer, and entrepreneur. The story unfolds as the old man relates his life story during the weeks prior to his death.

— Persuasion by Jane Austen was published 200 years ago in 1817. As with other Austen novels, there are worthy heroines who prevail over greed and vanity. None of Austen’s novels are quick reads, but they are certainly worth the effort. — Swing Time by Zadie Smith traces the friendship of two girls growing up in public housing in London from childhood into middle age. They meet in a dance class and bond over the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Dance and music play a large role in this book.

— Upstream by Mary Oliver is a collection of essays that explores the reliance on nature in her creative process. Anyone who loves Oliver’s poems will enjoy these essays. In the first essay, Oliver writes, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

— Miss Jane by Brad Watson is a fictional account of an ancestor of Watson’s who grew up in rural Mississippi with a handicap that made an ordinary life impossible for her. Jane lived to an old age without bitterness or complaint. Her attitude in overcoming her handicaps was inspirational. — Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng starts with the death of a teenage girl. Lydia is the favorite child of Chinese parents who expect her to achieve what they were unable to. This book reads like a mystery while telling how loving families can completely misunderstand each other. — The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben and The Genius of Birds by Jennifer Ackerman will change how you look at the natural world. According to Wohlleben, trees in the forest are social beings who nurture each other and communicate danger through secretion of scent or sound vibrations. I risk boring my friends with information from The Genius of Birds, and force my husband, John, to listen while I read stories of navigation, nest building and feats of intelligence. These two books are remarkable.

The New York Times Best Books of 2017

Fiction

Publisher’s Weekly Top 10 Books

Fiction

Nonfiction

The Boston Globe’s Best Fiction of 2017

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer Blameless by Claudio Magris, translated from the Italian by Anne Milano Appel The Burning Girl by Claire Messud The City Always Wins by Omar Robert Hamilton Cockfosters by Helen Simpson The End of Eddy by Édouard Louis, translated from the French by Michael Lucey Exit West by Mohsin Hamid Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell Frontier by Can Xue, translated from the Chinese by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie House of Names by Colm Toibin Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders The Lonely Hearts Hotel by Heather O’Neill The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy My Cat Yugoslavia by Pajtim Statovci, translated from the Finnish by David Hackston Pachinko by Min Jin Lee The Power by Naomi Alderman Savage Theories by Pola Oloixarac, translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

2018 is shaping up to be another great reading year.

A Case for Reading Fiction

Want to fight the onset of dementia? Pick up a good novel. Science also shows that reading literary fiction increases empathy and enhances the ability to see another perspective.

- by Carole McKellar

The most interesting research I’ve read is the work of psychologists Emanuele Castana and David Kidd published in the magazine “Science” in 2013. The researchers gave participants different reading assignments: excerpts from popular fiction, literary fiction, and nonfiction.

Popular fiction included mysteries, romances, and adventures. Literary fiction is difficult to define, but the test administrators chose works by award winning or canonical writers. After reading the texts, the subjects were given a test which judged their ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others. In other words, would the participants demonstrate a greater capacity for empathy. The results indicated that the nonfiction and popular fiction readers did not score high on measures of empathy. The readers of literary fiction have a far greater ability to relate to the lives of others. According to researchers, readers of literary fiction must infer the feelings and thoughts of characters. That is, they must engage “Theory of Mind processes.” The authors define Theory of Mind as “the human capacity to comprehend that other people hold beliefs and desires and that these may differ from one's own beliefs and desires.” Popular fiction portrays predictable characters and situations which only reenforce the reader’s expectations. These results might surprise those who assume that nonfiction is the genre that would best promote understanding. The Common Core State Standards Initiative, a controversial education initiative in wide use throughout the United States, details what K-12 students should know in language arts and mathematics at the end of each grade. Common Core curriculum guides emphasize nonfiction and downplays the importance of fiction.

It is concerning to me that parents and educators consider fiction to be less important to a child’s literacy than nonfiction. The stories most meaningful to me as a child were all make-believe. Reading fiction helps children understand what others are thinking and feeling. Such understanding could better prepare children for the complex world we live in today.

This topic reminds me of a wonderful novel I read recently titled “Exit West” by Moshin Hamid. It tells the story of two young people, Saeed and Nadia, in an unnamed country torn apart by civil war. They are forced to flee their homeland, and they eventually make their way to the United States. The remarkable thing about this book is the way the author expresses the tragedy of exile and dislocation from family. It’s a heart-wrenching story of loss which gave me a deeper understanding of the plight of refugees. “The Underground Railroad” by Colson Whitehead comes to mind as well. It tells the story of Cora, a young runaway slave, who escapes on a railroad that runs through underground tunnels. The depiction of her journey is harrowing and kept me engaged. “The Underground Railroad” won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Both novels feature magical elements. In “Exit West,” people pass through doors to find themselves in another country. “The Underground Railroad” asks readers to accept the idea that trains ran through tunnels built in the South. Such plot devices did not diminish the strong depiction of complex characters in difficult situations. Their stories were different from my own life, and they challenged me to understand their experiences. The case for reading fiction is strong. Reduced stress, greater empathy, increased vocabulary, and more creativity are good reasons to pick up a novel and dive in. In the words of American novelist, Joyce Carol Oates: “Reading is the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another’s skin, another’s voice, another’s soul.” A Darker Sort of Vision

There's Utopia and Dystopia - the perfect world versus one that's gone very, very wrong. Book columnist Carole McKellar looks the literature that has us cringing, but keeps us coming back for more.

Published in 1726, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels combines utopian and dystopian elements. Lemuel Gulliver traveled to countries with simplistic utopian qualities but others places he visited had dystopian aspects. His encounter with savage societies like the Yahoos sours Gulliver on human nature, and he changes from an optimist to a misanthrope by book’s end. This book was a favorite read during my college years with its satirical study of the good and bad elements of society.

Studying the timeline of dystopian fiction is useful in order to understand its popularity today. A guide to the history of dystopian fiction was posted by Patrick Brown on Goodreads in 2012. From the 1930s through the 1960s, dystopian literature was inspired by World War II, fascism, and communism. Controlling governments, loss of freedom, and the possibility of mass destruction were the inspiration for these classics: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932) It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (1935) 1984 by George Orwell (1949) Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1950) Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1952) On the Beach by Nevil Shute (1957) A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962) The second wave of dystopian fiction was concerned with identity politics and its anxiety about the human body. Novels from this period include: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985) V is for Vendetta by Alan Moore & David Lloyd (1988) The Children of Men by P.D. James (1992) Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005) Young Adult dystopian novels feature strong central characters in extreme circumstances. The phenomenal success of The Hunger Games trilogy spawned a multitude of novels that showcase a young hero or heroine successfully fighting against authoritarianism. Teens may worry that they face a dark, chaotic world with perpetual wars and ecological disasters. Dystopian fiction provides young people with exemplars of bravery who rise above adversity. Examples of the genre, which are often written as series, are: The Hunger Games (2008) by Suzanne Collins Divergent by Veronica Roth (2011) The Giver by Lois Lowry (1994) Uglies by Scott Westerfeld (2005) The Maze Runner by James Dashner (2009) The Unwind Dystology by Neal Shusterman (2009) Other dystopian literature that I recommend for good writing and compelling stories include: The Lorax by Dr. Seuss (1971): This “children’s book” features a warning of the effects of environmental degradation. The Road by Cormac McCarthy (2006): Awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize, this book tells the story of a man and his son’s journey after surviving an unspecified catastrophe destroys almost all life on earth. Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014): After a pandemic kills most of the world’s population, a troupe of traveling actors makes their way across the Great Lakes in search of survivors. American War, a debut novel by Omar El Akkad (2017): This chilling book takes place in 2075 and presents a second civil war in an America facing environmental destruction and societal collapse. Stories of disaster and misery may not appeal to every reader, but there are reasons for their popularity. Many are well written with intricate plots and admirable characters. Through them we see aspects of our own society, but the elements are more extreme. It’s interesting to imagine how we would react were we placed in similar circumstances. There is anxiety in today’s society and a concern for our future. Stories of dystopian societies make readers aware that average people can be heroic and find solutions to problems.

The TED talk below is only five minutes and gives an interesting overview of dystopia.

Fathers in Literature

Book columnist Carole McKellar takes a look at some of the best and the worst fathers in modern literature - and in real life, with Every Father's Daughter, edited by Pass Christian author Margaret McMullan

The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar was picked by The New York Times as one of the five best nonfiction books of 2016. It tells the true story of Matar’s father, who was kidnapped by Quaddafi’s forces and thrown into a secret prison in Libya. His family never saw him again, and the book tells of a son’s search for the truth of his father’s death and the tragic lives of Libyan refugees in a well-written story of familial love.

In The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti (from Parnassus Book First Editions Club) the father is a career criminal who tries to provide his daughter with a normal life. The story moves back and forth over time and weaves the story of the twelve times Samuel was shot during his life with his intense love for his dead wife and child. This book reads like a thriller, and I loved it.

Other admirable fathers in fiction:

Some less than admirable fictional fathers are:

Real-life fathers, both good and bad, are eloquently portrayed in Every Father’s Daughter: Twenty-four Women Writers Remember Their Fathers selected and presented by Pass Christian author, Margaret McMullan. I enjoyed essays by some of my favorite writers, including Alice Munro, Lee Smith, and Jane Smiley, but I equally enjoyed stories by writers unknown to me. Melora Wolff’s essay brought strong memories of my father when it began:

Maybe we remembered hugging the fathers when we were little girls and they were like trees, and we balanced on the tops of their shoes; maybe we remembered lifting out arms above our heads and waiting for our fathers to lift us up as if we were little ballerinas, into the air where we spun and squealed. The forward by Margaret McMullan is worth the price of the book. She wrote about her relationship with her father and their love of books: “When we talked about a book, we were always talking about important things.” If you are fortunate to have a living father, please enjoy one of those hugs described above. If, like me, you no longer have a father in your life, buy Every Father’s Daughter and read all day on June 18. Or, you could watch To Kill a Mockingbird and enjoy Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch, who exemplifies the best of fatherhood. For fathers who read this article, Happy Father’s Day. Jobs Writers Do

J.D. Salinger was the activities director on a cruise ship? William Faulkner as a bridge playing postmaster? Book columnist Carole McKellar takes a look at the day jobs of some of the world's finest writers.

Several well-known writers held full-time jobs in fields related to literature. Toni Morrison remained an editor at Random House and taught university literature classes while her novels were winning prizes and legions of readers. Virginia Woolf and her husband, Leonard, created and ran Hogarth Press, which is now an imprint of Random House.

Jorge Luis Borges, Argentine writer, and Philip Larkin, poet, were librarians. T.S. Eliot, one of the twentieth century’s major poets, taught school, worked at Lloyd’s Bank, and later joined a publishing company responsible for publishing English poets like W.H. Auden and Ted Hughes. Frank McCourt, famous for writing Angela’s Ashes, taught high school English in New York.

There is a tradition of physician writers dating back to antiquity. In mythology, Apollo was the god of both poetry and medicine. Perhaps the doctor’s role as observer allows a unique perspective of the human condition.

I became interested in the idea of doctors who are also authors after reading When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. A gifted neurosurgery resident, Kalanithi developed lung cancer at the age of 36 and died while writing the book. His gifts as a writer make the book shine as he details his life and impending death. He earned a master’s degree in English literature from Stanford University before following his love of science into medicine. Kalanithi’s life plan was to practice medicine while young, and to follow that with a second career as a writer. This book is beautiful and haunting, and I recommend it highly. Abraham Vergese, M.D., wrote the foreword to When Breath Becomes Air. Vergese stated that Paul Kalanithi’s “prose was unforgettable. Out of his pen he was spinning gold.” That is remarkable praise from any reviewer, but it carries extra weight coming from Vergese, the author of one of my favorite books, Cutting for Stone. Published in 2009, Cutting for Stone chronicles the lives of conjoined twins born in Ethiopia to an Indian mother who dies in childbirth. Vergese is an Indian physician born in Ethiopia, and his novel features much about the political climate and medical practices of the country.

More published authors who were trained as healers include:

In addition to long-term careers, it is interesting to learn about early jobs authors held and to imagine the effect of those jobs on subsequent writing. Agatha Christie worked in an apothecary, which provided knowledge of pharmaceuticals she later used in her mystery stories.

George Orwell was an Indian Imperial Police Officer until he contracted dengue fever and was sent back to England to recover. J.D. Salinger was the activities director on a luxury Caribbean cruise ship. John Steinbeck was a tour guide and manufacturer of mannequins. Kurt Vonnegut opened a Saab car dealership. After graduating from college with a degree in English, Stephen King couldn’t find a teaching job so he became a high school janitor. He said the movie Carrie was inspired during his time cleaning girls’ locker rooms. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, worked as a janitor in a mental hospital and tested LSD for a government-sponsored study. William Faulkner was a mailman (click here to read his spectacular letter of resignation), and Harper Lee worked for a while as an airline reservation clerk. The writers mentioned here achieved success through hard work and perseverance. Offering advice to those who aspire to become writers, Stephen King said, “If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.” Novelist Jack London wrote, “You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” I am an enthusiastic reader, and I try to write something every day. I enjoy looking at my old journals, filled with snippets of poems or observations about the day-to-day. I hope you take inspiration from these fine writers and don’t let your day job keep you from writing. Every Day a Poem

During National Poetry Month, take a news break and immerse yourself in the power of poems. You may not want the month to end.

- by Carole McKellar

Looking through an old notebook recently, I found the following excerpt from a speech delivered at Amherst College on October 26, 1963 by President John F. Kennedy for the groundbreaking ceremony of the Robert Frost Library. He was assassinated 27 days later. I was again struck by his eloquence on the power of poetry.

When power leads men toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses. For art establishes the basic human truth which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment. Knowledge of poetic forms is helpful but not essential to enjoy poetry. Poems frequently contain metaphors, similes, and personification. Remember those terms from freshman English? The Poetry Foundation (www.poetryfoundation.org) features a glossary of poetic terms with example poems.

Rhythm brings poems closer to song than other literary forms, which explains why some poems are best read aloud. Often the rhythm of a poem is arranged in a particular meter. In English, poetry often uses rhyme, but this is by no means universal. Rhythm and rhyme patterns make it difficult to translate from one language to another.

Poetry is no less an art because of its brevity. In fact, I would argue the opposite. As Henry David Thoreau wrote in a letter to a friend about the length of a story, “Not that the story need be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.” Poets’ skill in saying the most with few words is exemplified by the following verse from Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”: V. I do not know which to prefer, The beauty of inflections Or the beauty of innuendoes, The blackbird whistling Or just after.

The poet Andrew Motion, poet laureate of the United Kingdom from 1999 to 2009, said in Johns Hopkins Magazine that he wants to write poems that “look like a glass of water but turn out to be gin.”

Derek Walcott, a Nobel Prize winning poet, died on March 17, 2017 at the age of 87. I read about his death while writing this article. He was born on the island of St. Lucia, and he divided his time between the United States and his Caribbean home. His poetry is known for its musicality and visual imagery. His obituary in the New York Times included this excerpt of the poem “Islands” from the collection In a Green Night that exemplifies these traits in his poetry: I seek As climate seeks its style Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight, Cold as the curled wave, ordinary As a tumbler of island water. The Academy of American Poets, creator of National Poetry Month, lists 30 ways to celebrate the event on their website. Three of their suggested items on my to-do list are: 1) buy a book of poetry at my local independent bookstore, 2) memorize a poem, and 3) read a poem every day of the month. One of my favorite events is National Poem in Your Pocket Day on April 27, 2017. Simply carry copies of your favorite poems and share them with family, friends, or strangers. The Thrill of a Good Mystery

Shoofly book columnist Carole McKellar gives us a look at the different sub-genres of mystery novels and shares some of her all-time nail-biting favorites.

From the beginning, the mystery has taken many forms. Its various subgenres include:

Amateur Investigator

These stories feature a protagonist who is not a professional investigator or law enforcement officer. One recent favorite is “The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie” featuring a precocious 11-year-old girl, Flavia de Luce, who solves crimes in the sleepy English village of Bishop’s Lacey. In 1923, Dorothy L. Sayers intorduced Lord Peter Wimsey, an aristocrat who, with the help of his butler, Bunter, solves crimes in 20’s-era London. In the 1920s, Agatha Christie wrote the first of her 66 mysteries. Her most famous protagonists were the detective, Hercule Poirot, and Miss Marple. Cozy Cozy mysteries are essentially bloodless and neat. The victim won’t be missed and the solution is generally determined using emotional or logical reasoning. The cozy mystery usually takes place in a small town or village. Private detective Mysteries featuring private detectives are arguably the largest subgenre of mystery fiction. In addition to my early interest in Sherlock Holmes, I was a big Nero Wolfe fan. Nero Wolfe, created by Rex Stout, was a brilliant, eccentric detective who had a sidekick, Archie Goodwin, as his chronicler in much the same way that Dr. Watson wrote the adventures of Sherlock Holmes. In the 1930’s, Dashiell Hammett wrote ‘hard-boiled’ detective fiction. Among his well-known characters are Sam Spade from “The Maltese Falcon” and Nick and Nora Charles from “The Thin Man,” both of which became classic films. In the late 1930s, Raymond Chandler introduced his private detective, Philip Marlowe. Ross Macdonald, the pseudonym of Kenneth Millar, is credited with new levels of literary sophistication in his series featuring the detective Lew Archer. Other popular writers of detective fiction include Robert B. Parker, who wrote 40 novels about the private investigator, Spenser. John D. MacDonald created the much read Travis McGee series of mysteries and sold an estimated 70 million books in his career. In the 1970s, female private detectives gained popularity. Marcia Muller, Sara Peretsky, and Sue Grafton created tough, brainy females who don’t shy away from violence in a quest for the truth. Many of the private detective novels are part of a series. Sue Grafton, for example, is the author of the “alphabet series” featuring private investigator Kinsey Milhone. The 24th novel, “X,” was released in 2015.

Police Procedurals

Police crime novels are a subgenre of detective fiction that depicts the solving of crimes by the police. Some masters of the form and the detectives they created are Michael Connelly (Harry Bosch) , Jeffrey Deaver, (Lincoln Rhyme), John Sandford (Lucas Davenport), and James Patterson (Alex Cross), and Walter Mosley (Easy Rawlins). My favorite police series of mysteries was written by John Dunning and featured a Denver cop named Cliff Janeway. Dunning owned the Old Algonquin Bookstore in Denver, which specialized in rare books. Detective Janeway is an avid collector of rare first editions and the five books in the series are filled with information about the book trade. Legal Thrillers Lawyers are the major characters in this subgenre of crime fiction. John Grisham is arguably the most famous practitioner of the group. His breakout novel, “The Firm,” sold more than seven million copies. Linda Fairstein was a real-life District Attorney specializing in the prosecution of sex crimes, and her series, featuring the prosecutor Alexandra Cooper, concerns crimes against women. Medical Thrillers Authors with a medical background write most medical mysteries. Tess Gerritsen, retired physician, started out writing romantic thrillers, but gained prominence writing thrillers based on her medical experience. Patricia Cornwell worked as a technical writer for the Chief Medical Examiner of Virginia, which inspired Dr. Kay Scarpetta. Cornwell’s crime novels have sold more than 100 million copies. Spy novels Spy thrillers emerged in the early 20th century, inspired by rivalries between global powers and the emergence of modern intelligence agencies. The two World Wars, the Cold War, and the development of global terror networks provide the background for spy novels. The most famous fictional spy is the glamorous secret agent, James Bond, created by Ian Fleming. My personal favorite writer of the genre is John Le Carre, a former British spy. Le Carre creates anti-heroic protagonists who struggle with ethical issues and aren’t as one-dimensional as Bond.

Noir

Noir is a genre of crime fiction “characterized by cynicism, fatalism, and moral ambiguity.” Two varieties that have gained popularity are “Tartan Noir” and “Nordic Noir. Val McDermid is a Scottish crime writer, best known for a series of suspense novels featuring Dr. Tony Hill. Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy featuring Lisbeth Salander propelled Scandinavian crime fiction into a worldwide phenomenon. Peter Hoeg wrote the atmospheric novel, “Smilla’s Sense of Snow,” that is my personal favorite of the genre. Historical Set in a particular time period, historical mysteries are usually well researched. Ellis Peters wrote mysteries involving a Benedictine monk, Brother Cadfael, which are set in 12th century Britain. Umberto Eco wrote “The Name of the Rose” about a murder that took place in an Italian monastery in the 14th century. Elizabeth Peters, an Egyptologist, wrote a series of mysteries set in Egypt featuring Amelia Peabody, an Egyptologist and amateur crime solver. Romantic Suspense Not a favorite of mine, there are a few romance mysteries that I enjoyed. “Rebecca” by Daphne Du Maurier, a novel which has never gone out of print since its publication in 1938, is moody and unforgettable.“Possession” by A.S. Byatt, a 1990 Booker Prize winner, switches between the present and the Victorian era. The novel features two academics in pursuit of the true story of two Victorian poets believed to be in a love relationship. The academics fall for each other and echo the perceived relationship they are researching. Psychological Psychological thrillers emphasize the psychological states of the characters. “Gone Girl” by Gillian Flynn was a huge bestseller at its publication in 2012. “The Girl On the Train” by Paula Hawkins has sold more than 15 million copies in the U.S. alone. Perhaps the most terrifying psychological thriller was “The Silence of the Lambs” by Tomas Harris, published in 1988.

Narrowing the field of mystery fiction for reader recommendations is a difficult task. I’ve left out so many worthy authors and novels. Two websites for information about mystery fiction are www.stopyourekillingme.com and bestmysterybooks.com. “Stop, You’re Killing Me,” lists over 4,900 authors including winners of prestigious awards such as the Edgar Award, named for Edgar Allen Poe. The Mystery Writers of America gives the Edgar awards annually to honor the best in mystery fiction. A reader could not go wrong reading Edgar award-winning fiction.

My friend, Jane Lee, is an excellent source of mystery titles for me. Jane compiled a list she calls “A Dozen Mystery Classics” that I’d like to share it with you. 1. “The Maltese Falcon” by Dashiell Hammett 2. “The Big Sleep” by Raymond Chandler 3. “The Chill” by Ross MacDonald 4. “An Unsuitable Job for a Woman” by P.D. James 5. “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” by John LeCarre 6. “A Place of Execution” by Val McDermid 7. “The Silence of the Lambs” by Thomas Harris 8. “The Thief of Time” by Tony Hillerman 9. “Briarpatch” by Ross Thomas 10. “ Black Cherry Blues” by James Lee Burke 11. “The Judas Goat” by Robert B. Parker 12. “Strangers on a Train” by Patricia Highsmith Mysteries earn more than $730 million a year and are popular throughout the world. The basic appeal of mystery fiction is the ingenious resolution of a problem. The fact that the problem usually involves murder doesn’t deter the reader. We are content to observe the criminal at work as long as the wrongdoer is punished. The problem solver is smarter and tougher, and the solution of the puzzle usually appeals to our sense of right and wrong. In an uncertain world, the sense of order displayed in mystery and crime stories is satisfying to the reader. Best Books of 2016

Local book aficionado Carole McKellar polls other avid readers in the Bay to compile a "best of" list to help you find books you'll enjoy reading - and gifting - in the year ahead.

Some titles I read in 2016 were critically acclaimed, but others I enjoyed were not. Some were current while others were quite old. I read Emma by Jane Austen for the first time to celebrate its 200th anniversary.

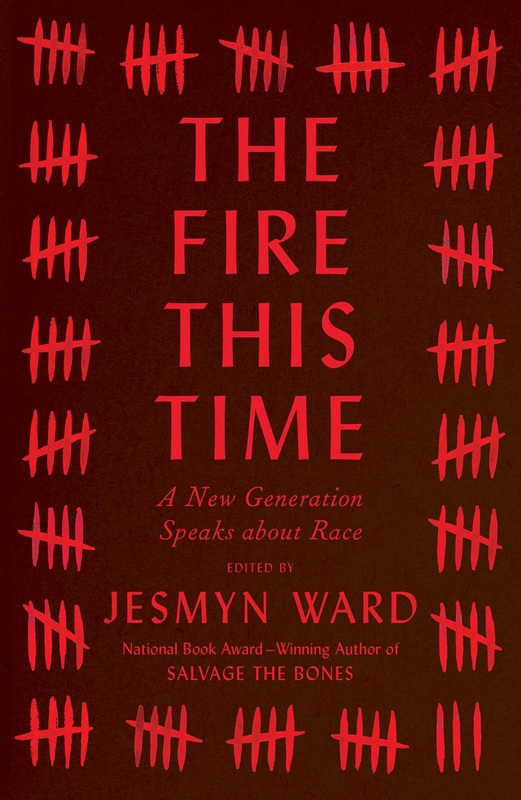

I belong to Parnassus Books First Edition Club. Parnassus is a Nashville independent bookstore owned by author Ann Patchett and Karen Hayes. Each month they select an outstanding book signed by a visiting author and mail it to their subscribers. I’ve participated for the past few years, but this was an exceptionally good year for membership. I’ll designate the books that I received from Parnassus. I keep a journal of all the books I read, and as I look back over the list I am struck by what a banner year this was for African American writers. Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates continues to be a best seller after winning the National Book Award for nonfiction in 2015. The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (Parnassus First Edition) won this year’s award for fiction. I loved the Whitehead book as well as these titles by other African Americans writers I read this year: The Mothers by Brit Bennett (Parnassus First Edition). This is her first novel, and it is remarkable. It tells the story of two friends from the point of view of the church “mothers.” The girls share the sadness that comes from being motherless. There are secrets and betrayals, but this is not a melodramatic book. It stayed with me long after I finished it. Another Brooklyn by Jacqueline Woodson (Parnassus First Edition). I loved Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming, a memoir in verse for young readers, and this book, written for adults, is a lovely read. Again, it’s about childhood friendships and the difficulty of sustaining them into adulthood. I had the pleasure of meeting Ms. Woodson at the Mississippi Book Festival in August. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi. Another debut novel by a young woman who was born in Ghana and raised in Huntsville, Alabama. Homegoing tells the story of two half-sisters, one sold into slavery while the other remained in Africa. The Fire This Time, edited by Jessmyn Ward. Ward and young African American writers provided essays, poems, and memoirs offering their perspective on race in 21st-century America. The book is an homage to The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin, which I read for the first time although it was first published in 1963. I wrote about these books in my October 2016 Shoofly column.

Other favorite books I read this past year are:

When Women Were Birds by Terry Tempest Williams. This is a beautiful, poetic memoir that I wrote about in November 2016. My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout (Parnassus First Edition). I love every book she writes, and this book is a worth successor to Olive Ketteridge and The Burgess Boys. My Brilliant Friend and The Story of a New Name by Elena Ferrante. These are the first two of the four Neapolitan novels. These books tell the story of two friends from Naples starting as children in the ’50s and tracing their lives to the present day in late middle age. I look forward to reading the remaining two novels in 2017. Free Men by Katy Simpson Smith (Parnassus First Edition). Smith is a young woman from Jackson, Mississippi, and she writes historical novels using the most beautiful prose. I read her first book, The Story of Land and Sea twice. Lila by Marilynne Robinson (Parnassus First Edition). This is the third book in a series that includes Gilead and Home, but you don’t have to read the other two to enjoy this heartbreaking story of love and redemption. H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald. It’s hard to say what I liked so much about an odd but appealing young woman who tells of training a hawk. It’s much more than a bird book, however, as Macdonald grieves the loss of her father, who taught her to view the world with wonder. A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles (Parnassus First Edition). The gentleman in question is a Russian nobleman who is sentenced to life within the Metropole Hotel for the crime of being an aristocrat. Count Rostov makes a life in confinement and thrives due to his intellect, curiosity, and kindness. This book was so convincing that I did research to find out if the count was real. Hold Still by Sally Mann. Subtitled A Memoir with Photographs, this book tells of the remarkable life and career of Mann. Commonwealth by Ann Patchett. I read this book in one day because I couldn’t put it down. It tells the story of two broken marriages and the damage done to the children. Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson. Stevenson is the founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative whose works won “reversals, relief or release for over 115 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row.” I wish everyone would read this book. Stevenson’s fascinating TED talk is available online. Imagine Me Gone by Adam Haslett (Parnassus First Edition). This novel describes the struggles of a family dealing with mental illness. The Dream Life of Astronauts: Stories by Patrick Ryan (Parnassus First Edition). These stories are all set around Cape Canaveral, but they are about much more than outer space. A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara. This hefty book tells a tragic story, but it was so good. I read it on a trip and felt travel time breeze by.

I asked my Bay Book Group to list some of their favorite books of the year. Here are some picks of the members who responded:

Allison Anderson, BSL Architect Allison loved the following books and gave them 5 stars: Before I Fall by Noah Hawley Swing Time by Zadie Smith Heroes of the Frontier by Dave Eggers The Sunlight Pilgrims by Jenni Fagan Jonathan Unleashed by Meg Rosoff Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry A Burglar’s Guide to the City by Geoff Manaugh Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders by Julianna Baggott The Girls by Emma Cline A Manual for Cleaning Women by Lucia Berlin The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks Cindy Williams, Bay High School Librarian Honeydew by Edith Pearlman. The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge (Young Adult novel) Jenny Bell, AdLib Communications owner Stitches by Anne Lamott. Although the book came out in 2013, Jenny wrote, “I reread it this year and found it very timely, at least for me.” Ann Weaver, NOAA Coastal Services Center Facilitator/Trainer When Women Were Birds by Terry Tempest Williams (who reminds me that one person can make a difference) A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit (reminds me of the importance of being alone outside) Dita McCarthy, Attorney Euphoria by Lily King. Said Dita, “I was pleased to learn more about an anthropologist character based on Margaret Mead. I particularly enjoyed the way it offered a look back at a school of anthropological thought that was considered progressive and groundbreaking at the time, and now, from our perspective, seems quaint. I also liked the way the author treated the inherent problems with such anthropological studies of remote tribes. By inserting themselves into the tribes, both out of a thirst for knowledge and also greed and desire for fame, they are indeed affecting the tribe.”

The New York Times 10 Best Book of 2016 Fiction

The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan The North Water by Ian McGuire The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith War and Turpentine by Stefan Hertmans, translated by David McKay Nonfiction At the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right by Jane Mayer Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond In the Darkroom by Susan Faludi The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar The Washington Post 10 Best Books of 2016 Fiction Commonwealth by Ann Patchett Swing Time by Zadie Smith The Trespasser by Tana French The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead News of the World by Paulette Jiles Nonfiction Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain’s Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War by Ben Macintyre Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets by Svetlana Alexievich, translated by Bela Shayevich

I look forward to 2017, which promises to be another good year for readers. I have a stack of books on my nightstand that includes Moonglow by Michael Chabon, LaRose by Louise Erdrich, The Trespasser by Tana French, and The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen.

George Saunders’s first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, will be released in February, and I can’t wait. Swing Time by Zadie Smith and News of the World by Paulette Jiles are on my list of must-reads. I hope some of the books mentioned above spark your interest and lead you to the bookstore or library. David Sedaris

One of the country's most beloved humorists keeps fans entertained with honest observations and an irreverent wit.

- story by Carole McKellar

Ira Glass discovered Sedaris in a Chicago club reading from his diaries. Glass asked him to appear on his local radio program, “The Wild Room.” Sedaris read “The Santaland Diaries,” which came from his experiences as an elf at Macy’s department store during Christmas. Listeners loved the story and it led to frequent appearances on NPR as well as a book deal. Sedaris credits Glass for his early success, and he is a frequent contributor to Glass’s popular NPR show, “This American Life.”

David’s first book, “Barrel Fever,” was published in 1994, and since then he has written a total of eight books of stories and essays. They usually have farfetched names such as “Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim” and “Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls.” In addition to books, Sedaris is featured in numerous periodicals. The New Yorker has published more than forty of his essays.

My favorite Sedaris book is “Me Talk Pretty One Day,” published in 2000. The first story tells of the period in elementary school when David saw a speech therapist. To avoid his lisp, he consulted a pocket thesaurus for synonyms of all common words containing the “s” sound. The word “yes” became “correct” or “affirmative.” Plurals and possessives posed problems, but he got around it by referring to “dogs” as “a dog or two” and “Jane’s book” as “the book belonging to Jane.” I enjoyed that story because I’m a retired public school speech language pathologist.

“Me Talk Pretty One Day” gets its title from his attempts to learn the French language while living in Paris with his partner Hugh. Initially, David typed French words that he committed to memory on index cards such as "exorcism," "death penalty," and "witch doctor." Later, he enrolled in a French immersion class. He reported that conversations in French with classmates sounded much like, “That be common for I, also, but be more strong, you. Much work and someday you talk pretty. People start love you soon. Maybe tomorrow, okay.” After years in France, David and Hugh moved to West Sussex, England, where they still live. As with David’s family, Hugh is featured in many essays where he is usually portrayed as the reasonable partner on David’s zany misadventures. Sedaris recently wrote a story about his obsession with his Fitbit. He roamed the English countryside picking up garbage and chalking up steps. He wrote, “I look back on the days I averaged only 30,000 steps, and think, Honestly, how lazy can you get?” Sedaris has an irreverent sense of humor and some stories may offend the faint of heart. Referring to his family, he said, “We were not hugging people. In terms of emotional comfort it was our belief that no amount of physical contact could match the healing powers of a well made cocktail.”

"When Women Were Birds"

An environmentalist writes a moving - and best-selling memoir based on her life growing up in Utah. Shoofly book columnist Carole McKellar shares elements that have made this book a favorite in her library.

Williams’ mother was a private person who often said, “I don’t like people knowing my thoughts.” Throughout the book, Terry speculates on the mystery of the blank books:

“My Mother’s Journals are an act of defiance. My Mother’s Journals are an act of aggression. My Mother’s Journals are an act of modesty.

Terry began writing as a child, confirming from an early age that she “experienced each encounter of my life twice: once in the world, and once again on the page.” Unlike her mother, she states, “I cannot think without a pen in hand. If I don’t write it down, it doesn’t exist.”

In fifty-four short chapters, Terry explores of the experiences that shaped her life. She learned a love of nature from her parents and her paternal grandmother, who was an inveterate bird watcher. She gave Terry her first field guide to birds at the age of five. Williams writes, “It is the first book I remember taking to bed. Beneath my covers, I held a flashlight in one hand and the field guide in the other. I studied each painted bird carefully and took them into my dreams.” While working at a bookstore in Salt Lake City, Williams met Brooke, to whom she has been married for more than forty years. She admired his book selections which included Peterson’s “Field Guide to Western Birds.” Of her marriage, Terry wrote, “We have never stopped loving all things wild and unruly, including each other.” In one particularly amusing chapter, Williams described her first adult job as a biology teacher at the conservative Carden School in Salt Lake City. The headmistress insisted that Terry never use the word “biology” with her students because it “denotes sexual reproduction, and we will have none of that here.” When asked if she was an environmentalist, Terry replied that she indeed was. The headmaster leaned toward her and asked, “Did you know that the Devil is an environmentalist?”

In addition to championing conservation of public land, Williams is an advocate for women’s health issues. Nine members of the Tempest family have had breast cancer including her mother and grandmother. Williams believes that exposure to radiation from the Nevada Test Site between 1951 and 1962 is the reason so many members of her family have been affected by cancer.

In describing the power of poetry in her life, Terry credits a speech pathologist with helping her overcome a speech impediment. “I did not find my voice—my voice found me through the compassion of a teacher who understood how poetry transforms us through the elegance and lyricism of language.” Wangari Maathai, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, was another mentor to Terry. The Green Belt Movement founded by Maathai empowered women in Kenya to plant forty-three million trees in response to the environmental crisis of deforestation. Working alongside Maathai and the women in Kenya inspired Williams to start a similar movement in Utah. After hearing of Maathai’s death, Terry sighted a ruby-throated hummingbird hovering nearby. “This was Wangari’s favorite bird, the one who put out a forest fire, one beak full of water at a time.” This story was told by Maathai to illustrate how small actions can change the world.

Terry Tempest Williams’ writing is both poetic and wise. She is a marvelous story teller. I’ve read this book twice in the past year and given it to friends. She has shown me that there are many ways to experience and react to the world, and the choice is ours.

“How shall I live? I want to feel both the beauty and the pain of the age we are living in. I want to survive my life without becoming numb. I want to speak and comprehend words of wounding without having these words become the landscape where I dwell. I want to possess a light touch that can elevate darkness to the realm of stars.” Picador, AN and imprint of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, published this edition. The book itself is visually and tactually beautiful. I went to the Picador Press website, www.picador.com, to find out more about the books they publish. The site contains a book blog which recently featured “beautiful and unique book covers.” I recommend all book lovers explore their book selections and this book blog. The Fire This TimeAn in-depth look at "The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race," edited by acclaimed coast author, Jesmyn Ward. - by Carole McKellar

For this is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men

The following are a few of the 18 contributors to “The Fire This Time”:

Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, wrote “The Warmth of Other Suns,” which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. Subtitled “The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration,” this beautifully written book earned a place of honor on my bookshelves. Wilkerson wrote a short, powerful essay titled “Where Do We Go From Here?” which culminates with, “We must keep our faith even as we work to make our country live up to its creed. And we must know deep in our bones and in our hearts that if the ancestors could survive the Middle Passage, we can survive anything.” Natasha Trethewey, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and former U.S. Poet Laureate, has deep roots in the Gulf Coast that feature in many of her poems, including the one she submitted to the collection titled “Theories of Time and Space." Click here to watch the video of Trethewey reading the poem. Edwidge Danticat, a Haitian-American writer and author of the haunting novel, “Claire of the Sea Light,” has written fiction and nonfiction for both children and adults. Mother-daughter relationships, a recurring theme of Danticat’s prose, featured in the final essay in this collection, “Message to My Daughters.” She tells her daughters, “Please know that there will be times when some people might be hostile or even violent to you for reasons that have nothing to do with your beauty, your humor, or your grace, but only your race and the color of your skin. Please don’t let this restrict your freedom, break your spirit, or kill your joy.” To escape the wrath of his stepfather at home, Garnette Cadogan started walking the streets of his native Jamaica. Those streets could be violent, but nothing prepared him for walking through the streets as a black man in America. In New Orleans, where he attended college, and later in New York he learned not to wear certain clothes, stop suddenly, stand on the corner, or run. In his essay on walking, “Black and Blue,” he talks about his awareness that his actions may provoke alarm simply because he is a man of color. In addition to the introduction, Jesmyn Ward wrote an essay titled “Cracking the Code.” She recalls ordering genetic testing kits for her father, her mother, and herself. Her father was 51 percent Native American, and her mother was 55 percent European. Jesmyn was 40 percent European, 32 percent sub-Saharan African, 25 percent Native American, and 1 percent North African. She “understands the world through the prism of being a black American,” but she pays homage to other aspects of her heritage, such as a love of French films, “Doctor Who,” and the poetry of Pablo Neruda. Her essay was humorous, but it left me questioning perceptions of race. I’ve written about the writers whose works I’ve read and admired in the past, but some of the contributors were new to me. While at the Mississippi Book Festival on August 20, I attended a panel moderated by Ms. Ward featuring Kiese Laymon, Honorée Jeffers, Garnette Cadogan, and Kima Jones. At the time, I was reading “Long Division” by Mr. Laymon, and found it laugh-out-loud funny. His essay, “Da Art of Storytellin’, A Prequel,” is a loving tribute to his grandmother, but his humor is amply evident. I found all the essays in “The Fire This Time” well written and thought provoking. These are indeed a group of talented young writers, and I look forward to reading their future work. I think James Baldwin would be honored that his book inspired this collection. He said, “You write in order to change the world. ... If you alter, even by a millimeter, the way people look at reality, then you can change it.” Race is an uncomfortable topic for many people to discuss openly, but America must reconcile its violent past if it is to change the future. In a recent New York Times/CBS News poll, 69 percent of Americans said race relations are generally bad. That’s unacceptable if we want our nation to fulfill its promise. Some other books written by African American writers that I have enjoyed recently: “Another Brooklyn” by Jacqueline Woodson (Harper Collins, 192 pp.) “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates (Spiegel & Grau, 176 pp.) “Homegoing” by Yaa Gyasi (Knopf, 320 pp.) (Gyasi was born in Ghana and grew up in Alabama) “The Underground Railroad” by Colson Whitehead (Doubleday, 320 pp.) “Voyage of the Sable Venus and Other Poems” by Robin Coste Lewis (Knopf, 160 pp.) (2015 National Book Award winner; her family is from New Orleans) “The Fishermen” by Chigozie Obioma (Back Bay Books, 304 pp.) (Born in Nigeria, Obioma teaches creative writing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln) Finally, from “Salt” by Nayyiral Waheed (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 258 pp.) (I love these poems): even the small poems mean something. They are often whales in the bodies of tiny fish. The Mississippi Book Festival

This second annual literary festival in Jackson featured several prominent coast writers and drew thousands of readers from across the region.

- story by Carole McKellar, photography by Ellis Anderson

The inaugural event in 2015 had an estimated economic impact of $325,000, thanks to approximately 3,700 attendees — and event organizers had been expecting only about a thousand visitors. When I went last year, I couldn’t get into several events due to overcrowding. This year was even bigger and better, but thanks to expanded venues and strategic planning, I found seats for the panels and interviews that most interested me.

This year’s festival featured more than 200 authors, several of them from the coast. Jesmyn Ward and Margaret McMullan, both Pass Christian residents, moderated panels featuring well-known writers. Author, playwright, and Shoofly contributor Rheta Grimsley Johnson participated in two events, one of which was the closing feature, the Mississippi Experience. That panel’s moderator was Festival board member Scott Naugle, owner of Pass Books and a Shoofly sponsor. All authors attending the festival signed their books in a special tent on the lawn of the capitol. Lemuria Books, one of the state’s premier bookstores, set up a large tent nearby to sell featured works.

Curious George attended to celebrate his 75th birthday and entertain young book lovers. The kickoff event of the festival, held in the sanctuary of Galloway Methodist Church, was an interview with Kate DiCamillo, noted author of young adult fiction. The auditorium was filled with Jackson public school children, each of whom received a copy of Ms. DiCamillo’s book, “Because of Winn-Dixie.”

Jacqueline Woodson, recently named the Young People’s Poet Laureate by the Poetry Foundation, was interviewed in an afternoon session by poet Honoree Jeffers. Listening to them talk felt like eavesdropping on a conversation between two friends. Even Ms. Woodson’s conversation is poetic. I loved “Brown Girl Dreaming,” and just finished reading “Another Brooklyn.” Afterward, I overcame my natural reluctance and introduced myself to Ms. Woodson as a fan. Thankfully, she was warm and friendly. In addition to being poet laureate, Ms. Woodson won the National Book Award in 2014 for “Brown Girl Dreaming,” a memoir in verse. That book contains some of the most beautiful poems I’ve ever read, and their aggregate as an autobiography is an astounding work.

Jesmyn Ward, winner of the 2011 National Book Award for “Salvage the Bones,” moderated a panel discussion with four contributors to “The Fire This Time,” a collection of essays that Ward edited and which pays tribute to James Baldwin’s 1963 book of the same name. The newer volume focuses on issues of race in present day America as realized by some important young voices.

A panel that included Rheta Grimsley Johnson gathered to discuss memoir writing. Rheta read one of my favorite anecdotes from her latest book about her down-the-road neighbor in Iuka, Mississippi. Her fellow panelists were as amusing, and the room was filled with laughter the entire session. For a review of Rheta’s latest book, “The Dogs Buried Over the Bridge: A Memoir in Dog Years,” check the Bay Reads archives for March, 2016. C-Span 2 aired most sessions live on Book TV, and I’m told the sessions will be available for viewing in October on the Festival website, www.msbookfestival.com. I urge you to join me next year for Mississippi’s “Literary Lawn Party”! An Exemplary School Librarian

An interview with coast school librarian Cindy Williams reveals a woman who loves her job - and eager to share some of her favorite authors and books.

- by Carole McKellar

The Bay-Waveland School District is fortunate to have Cindy Williams as the Bay High School librarian. Cindy graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in banking and finance before discovering that she could choose a career based upon her love of reading. She earned a master’s degree in Library and Information Science from the University of Southern Mississippi. After college, Cindy became the librarian at Pineville Elementary in Pass Christian for two years followed by 15 years at Coast Episcopal School.

Cindy Williams (right) with author Deborah Wiles Cindy Williams (right) with author Deborah Wiles

While at Coast Episcopal, Cindy initiated an ‘Author’s Fair’, an ‘Illustrator’s Fair’, and a ‘Harry Potter Breakfast’, among other literary celebrations. Her co-worker, Kat Fitzpatrick, remembered that Cindy was "a genius for getting volunteers and making the work seem fun." Cindy joined the faculty at Bay High two years ago and accepted the new challenge of using her enthusiasm and innovation to motivate older students.

During her first year at BHS, Cindy started a Bay High Book Club, which boasts 30 members. According to Cindy, club membership is casual, and students are free to decide which books they would like to read and discuss. Cindy initially envisioned a book list generated by the students, but found that they wanted her suggestions. In typical fashion, Cindy employed all of her book review tools—Booklist, Hornbook,book awards, blogs, etc—to make sure she chose books that had the best chance of engaging the students. The list reads like a Who’s Who of the best YA authors:

“Every Day” by David Levithan

“Young Elites” by Marie Lu “Paper Towns” by John Green “Where I Want to Be” by Adele Griffin “1984” by George Orwell “Unwind” by Neal Shusterman “Unbroken” (Young Adult Adaptation) by Laura Hillenbrand “We Were Liars” by E. Lockhart “Shipbreaker” by Paulo Bacigalupi “Midwinter Blood” by Marcus Sedgwick “Code Name Verity” by Elizabeth Wein

For the past 2 years, Cindy has focused on increasing circulation and student interest in the library. The library is open before and after school, as well as during lunch, and students can come there at any time during the school day with teacher permission. Students can check out books, study, conduct research, or use the computers. The book club helped make students comfortable coming to the library for socialization as well.