Bay St. Louis Beachfront Festival

Pat Murphy reveals the history of the Bay's popular Beachfront festival, which ran from 1980 to the early 90s.

St. Mary Cemetery

Walk through one of the loveliest resting places in Hancock County with Becky Orfila, who introduces some town residents who are long passed from this earth.

- by Rebecca Orfila

With evidence remaining of storms, winds, and time, this peaceful graveyard is the resting place for approximately 2,000 individuals. The cemetery is owned and managed by Our Lady of the Gulf Church in Bay St. Louis. A simple walk through this cemetery brings one closer to the resting places of many families from Hancock County.

Several graves predate the 1872 dedication date. Blanche Teresa Scull died in 1852. The 15-year-old was the daughter of Hewes Charles Scull and his wife, Louisiana Philipana Scull (they were cousins) of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Blanche was attending St. Joseph’s Open School when she died. She is buried in St. Mary Cemetery, in the northeast corner of the Sisters of St. Joseph plot. (Plot: N10-26: see how to find the gravesite by number at the end of this article). Nicolas Caron/Carron was buried in St. Mary in 1859. Nicolas was married to Ursule Justine Saucier, the daughter Phillipe Pierre Saucier, Sr. In the 1850 U.S. Census, it was reported that Caron had properties valued at $9,000, making him a member of the top five wealthiest men in Shieldsboro (N09-01). The first burials following the cemetery dedication in 1872 by Father Henry LeDuc — with the blessings of Bishop Richard Oliver Gerow, Diocese of Natchez — were for Sisters Estelle Astier (1872), St. Peter Elder (1874), Ellienna Alloid (1878), and Louise Felicity Robinson (1880). These initial interments established a dedicated plot for the Sisters of St. Joseph (N10-03). In the Bishop’s report, “Catholicism in Mississippi,” published in 1939, the Bishop refers to St. Mary Cemetery in several places.

The death and burials of the Very Reverend Florimon J. Blanc and the Very Reverend Aloise van Waeberghe are recorded in Bishop Gerow’s report. The Bishop’s statement identifies that Blanc and van Waeberghe were interred in a vault at “Calvary,” which was an underground vault and aboveground monument located at the intersection of the east/west trending cemetery road and the first right-side roadway.

One undated historical plat map has survived and a circular area is identified in handwritten script as Calvary. The circumference of Calvary measured 36 feet in circumference or 23 ft in diameter. No aboveground evidence of the Calvary remains and it is unknown whether an underground vault and burials exist. It is likely that the Calvary was destroyed by one of the major storms in the area. A familiar name in Bay St. Louis, Clement Robert Bontemp, was interred at St. Mary in 1918 following his death from battle wounds received at Chateau-Thierry, France (N02-15). His military grave record shows he was born Nov. 6, 1893, Bay St. Louis, MS and served in the sixth regiment of the U. S. Marines during World War II. The American Legion Post 139 in Bay St. Louis was founded in 1923 and named after Bontemp. The Italian Society Mausoleum has one of the largest funerary structures in St. Mary Cemetery. The Society vault is Italianate in style and marks a section dedicated to the entombments and interments of society members.

A member of the engineering and maintenance crew of the Delta Steamship Line ship, the SS Del Sud, Funston Mauffray died on April 27, 1959 (S07-23d). The ship was only 11 days out of port at the time of his death. Two weeks later, Mauffray was buried at sea (South Pacific). Mauffray was 39 at the time of his death and was a 1921 graduate of St. Stanislaus.

Jerry Costollo was a brakeman on a train of 18 loaded cars near Birmingham when the locomotive engineer failed to stop and ran into another train on the rail, killing Costollo, the engineer, and a train mechanic. The story of the railroad accident was telegraphed and published in the May 18, 1891 issue of the New York Herald. A worn memorial stone dedicated to Costollo is placed near the graves of Mary and Hanora Costollo (N08-15). A grave maker on the north side of the cemetery captures the eye in the vivid sunlight. An elegant white marble headstone marks the grave of Arsene Bontemp Estapa (N02-02). Though stained with green moss and dirt, what is unique about this headstone is the brightness of the marble and the depth of the engraving. Her place of birth is inscribed in graceful print and in the musical voice of the French language — “ne a la Baie S. Louis" (from Bay St. Louis). She died on October 10, 1875, in Hancock County, Mississippi. It goes without saying that there is an otherworldly nature to cemeteries. Whether it is based on our religious beliefs or our distance from decades or centuries of local life, the more we learn about cemeteries, the more they contribute to our understanding of the history of humans. Information regarding burials and purchasing plots in St. Mary’s should be directed to the Our Lady of the Gulf rectory at 228-467-6509. How to find a grave in St. Mary Cemetery

The Hancock County Historical Society surveyed and recorded St. Mary Cemetery, which is divided into a North and South sections, beginning with Necaise Street.

To find a gravesite, start on the main road through the cemetery and walk westward counting row numbers, beginning with #1. Based on the location data provided above, find the proper row. For example, Funston Mauffray is buried in S07-23d. To get to his grave, walk seven rows west then turn south. Counting gravesites southward, Mauffray will be buried in the twenty-third gravesite, along with other family members. Information regarding burials and purchasing plots in St. Mary’s should be directed to the Our Lady of the Gulf rectory at 228-467-6509. My Cedar Point Home

Pat Murphy's recollections of old Bay St. Louis take us across Highway 90 and to Dunbar Pier, the old Bay Waveland Yacht Club and down Felicity Street, where his childhood home once stood.

A House With a Diary - 526 Citizen Street

When they purchased their historic home in 2014, Chris and Patricia Cheek didn't realize that it came complete with its own journal, started 65 years before - one that contained a few surprises.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson Valena Cecilia McArthur Jones

A church and two schools bear her name: Valena C. Jones. Her life wasn't a long one, but she left a lasting legacy.

- by Rebecca Orfila

Following her matriculation, Jones was named principal of the Bay St. Louis Negro School where she taught until 1897 when she accepted a position in New Orleans at McDonough School #24. During the McDonough teaching period, 1897 to 1901, Jones was voted the most popular black teacher in the city. When she married Rev. Robert Elijah Jones of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1901, her career as an educator ended. Married women were not allowed to teach in public schools at that time.

After her marriage, Valena helped her husband edit and publish the Southwestern Christian Advocate, a periodical of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Three years following her death in 1917, Rev. Robert E. Jones, Valena’s husband, was elected Bishop of the New Orleans Area (central Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas). Three centers of education and spirituality were named in her honor since her death: Valena C. Jones School in New Orleans and Bay St. Louis, and the Valena C. Jones United Methodist Church on Sycamore Street in Bay St. Louis.

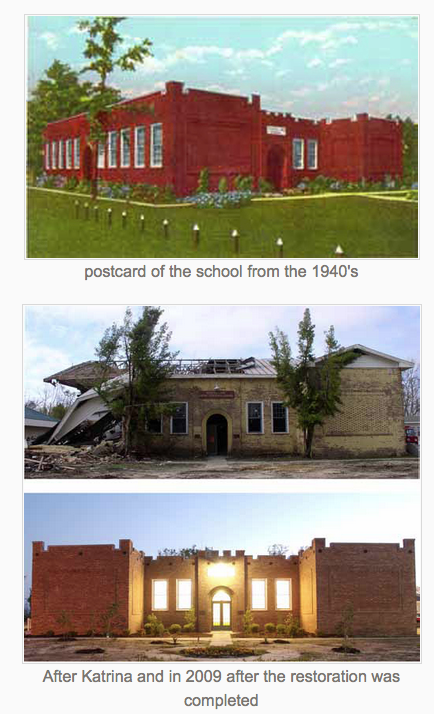

Beginning in 1910, a citizens group in New Orleans 7th Ward saw the need in their community for a neighborhood school. Between fundraisers like dinners and dances, the group was able to purchase four acres for the construction of a small school. The first school was destroyed by weather events in 1916 and was replaced by a new structure built in 1918 near the intersection of Annette Street and North Miro Street.

The 1918 school was the first structure named in honor of Valena Jones. Due to its growing enrollment, the small school was replaced in 1929 with an impressive brick, three-story structure. According to the Chicago World issue of November 2, 1929, the school was “named after Mrs. Valena MacArthur Jones, formerly a teacher in the public school system in recognition of her outstanding ability as a teacher and for her uplifting influences among the people of her race.” Back in Bay St. Louis, St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church provided religious education to the black population and was originally located on Washington Street in Bay St. Louis. The first structure was replaced in 1922 with a larger church. Built in 1880 to provide religious education and support for blacks in the area, growing attendance levels required the construction of a larger church in 1922.

The influence of Valena McArthur Jones did not stop at the conclusion of her life or with the construction of the buildings that carry her name. In an oral history conducted by the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, Alonzo Merdis Daniels recollected excitement as a youngster for attending school “with the other fellows in our community.”

Daniels waited impatiently until he turned six to attend Valena C. Jones Public School in Bay St. Louis. Daniels attended from first through tenth grades, the highest level attainable at the school. Following Jones School, he attended St. Rose and completed his high school graduation with the class of 1931. While reminiscing, he praised his English teacher, Grace Claudia Jones Minor, one of Valena Jones’ daughters. Mrs. Jones died in New Orleans in 1917. She was interred in Greenwood Cemetery. The grave is unmarked but can be found in Plot 515, Pine Cedar Aloe, Daughters of Louisiana, Gravesite 5. If anyone has more information about Valena C. Jones and would like to add to the historical record of her life, please contact us at publisher@bslshoofly.com. Waveland's Ground Zero Museum Under New Director

A place that honors the survivors and volunteers who experienced the wrath and the aftermath of the most destructive hurricane in American history.

- story and photos by Ana Balka

If one did not take a close look at these, one might assume they were a post-Katrina gesture from a quilting society somewhere, but no: these are all the work of master quilting artist Solveig Wells, who had homes in Canada and Bay St. Louis and who completed these all from salvaged fabrics over 16 months in 2006-’07. Wells’ husband David donated the exquisite collection to the museum following Solveig’s death in 2013.

Museum volunteer and Waveland resident Carol Kerr says that in the weeks since the museum’s reopening visitors have reacted positively and sometimes emotionally to the museum’s collection of photos, art, and artifacts, which paint a distinctive portrait of Waveland before, during, and after Katrina.

Carol showed me the auditorium, where local students in Waveland’s M.A.P. (Music, Arts & Practicality, a non-profit enrichment program providing free theater and choir experiences for area students) summer theater camp have been rehearsing “The Lion King” for presentation on the auditorium stage July 16-17.

This is a facet ofnew director Kathy Pinn’s long-range vision for the Ground Zero Museum building as a gathering place: a place that builds community, as well as being a center for learning about the storm, about Waveland history, and about what makes Waveland such a special place. Pinn has long fostered community in Waveland. A former president of both the Coleman Avenue Coalition and the Waveland Community Coalition (and incidentally a M.A.P. co-founder), Pinn and her husband Ron are moving back to Waveland after five years in Illinois specifically to get back to the home they love, and for Kathy to assume her role as museum director. Pinn says that the dozens of museum visitors in its first month have included residents of 15 other states, some who had never been to the area, some post-Katrina volunteers. For locals, touring the museum can be cathartic. “Seeing the waterline, seeing the pictures on the wall, then the H.C. Porter exhibit, it’s very moving,” Pinn says. “Backyards and Beyond” is a multimedia exhibit by artist H.C. Porter and collaborators Karole Sessums and Gretchen Haien. Porter and Sessums photographed and recorded hundreds of Mississippians in the year following Katrina, creating a nationally touring exhibit that features Porter’s mixed media paintings and accompanying audio in which the portraits’ subjects express the reality of displacement and loss through their own stories.

Ground Zero’s Porter exhibit, sponsored by Mississippi Power, contains eight of the paintings, with audio guides. The floor is covered in photo-printed tiles that together comprise a life-sized portrait of the slabbed remains of a Waveland home.

The room feels chapel-like, bringing human shape to the unspeakable. I can see how it might uncover long-buried emotions in those who survived the storm.

“All of that is sometimes a little overwhelming,” Pinn says, “But then we go into the Waveland room.”

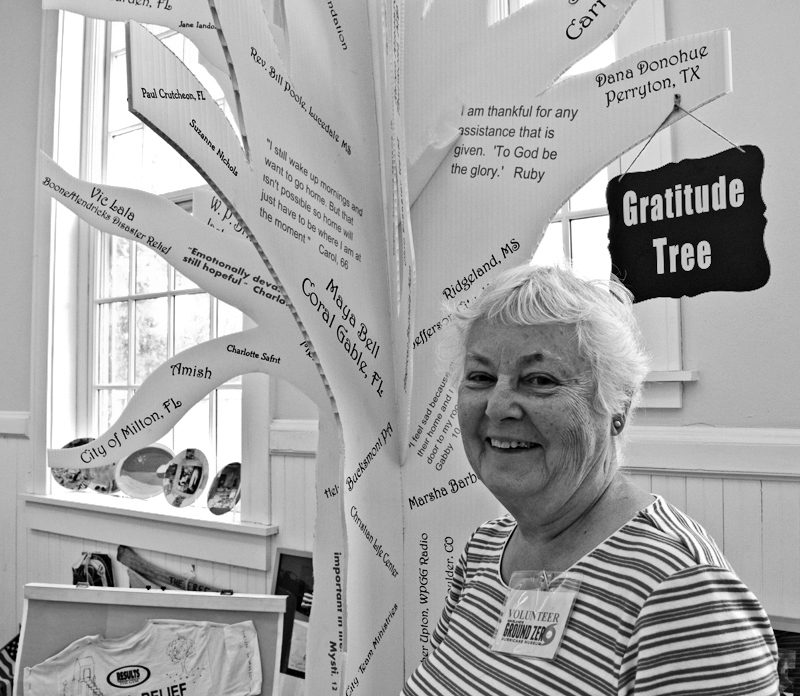

Many displays in the Waveland Room represent steps toward healing. There are binders with hundreds of handwritten, individual “Storm Stories” by survivors that visitors can thumb through, and throughout the room there are photo collages, quilts, signed shirts, and other outpourings of love from well-wishers and volunteers around the country. A large cardboard “Gratitude Tree” stands covered in names and quotes. I photograph volunteer Carol next to her own words about home being wherever she is, because she cannot go home. In a corner, an assemblage by mixed media artist Lori Gordon depicts the clothes that hung from trees after the storm.

The room also contains historical artifacts: one wall is festooned with hand-painted versions of Boy Scout merit badges from the days Scouts held meetings in that very room in the ’50s, as well as photos of students, teachers, and sports teams from Waveland Grammar School days in the ’30s and ’40s. A glass case contains memorabilia from hurricane Camille.

A somewhat surreal herd of carousel animal figures gallop, hop, and swim at the back of the room, but that is part of the museum’s evolving nature. The Port Townsend (Washington) Carousel Association donated the Carousel of the Olympic Sea, an original by Bill Dentzel of the Denztel family of carousel makers, to Waveland after Katrina. Its size prohibits assembly in the museum building, so while the carousel has a permanent home at the museum, its location has yet to be defined.

Pinn knows that visitors will come away from the museum experience with a positive awareness of all that Waveland is and has achieved: “I’d like people to understand that part of it: It happened, we got through it, and now look at us.”

Hancock County Historical Society: Volunteer Driven

A crackerjack group of volunteers keeps the energy humming at one of the most respected historical societies in the country.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Rebecca Orfila and Ellis Anderson

The HCHS volunteer cohort consists of individuals with a love for history or a desire to give back to their community. Gifted with various talents and interests, each volunteer is invited to work in their area of interest or, with the assistance of the volunteer staff, match their skills with new or unfinished projects. With a smile, Charles Gray, the Executive Director of HCHS, confirmed that volunteers are provided a wide berth on their volunteerism and schedule: “Whatever works for you, works for us.”

Volunteers can serve in many ways at HCHS. Several professional and avocational historians contribute quality articles to the monthly newsletter, The Historian of Hancock County. During a post-luncheon chat with a few of the volunteers, James Keating spoke of being inspired by Eddie Coleman (the editor of The Historian) to pursue his interest in the economic history of this area. Keating, a New Orleans native and retired physician, has been published in The Historian several times, most recently in the April 2016 issue with his article “The Turpentine Industry in Hancock County.” Other well-known contributors to The Historian include Coleman, Scott Bagley, and Russell Guerin. According to Coleman, submissions for The Historian are invited. If you are interested in submitting an article, contact the Society via the address or number listed below.  Scott Bagley Scott Bagley

Historical societies gather, organize, and share information with researchers, genealogists, visitors, and other interested parties by making paper or digital documents available to the public. HCHS maintains documents and indexes of local cemetery records, for example. These resources — and much more — are available to the general public at the Lobrano House in downtown Bay St. Louis and on the Society’s ever-expanding website, where the cache of digitized records available for research increases every day.

Through the efforts of volunteer researchers, writers, computer aficionados, organizers, and “boots on the ground” folks, the Society continues to add to their collection. Many local and New Orleans families have donated records and images, which are scanned for archival and research purposes. Personal materials, including private letters, tell stories and even provide details on confidential matters. According to Gray and Coleman, the Society does not censor when asked for information. No matter what the contents of a letter, album, or image, any donation will be made available to the public. “We don’t want any secrets,” Gray said. The amount and accessibility of resources at the Hancock County Historical Society has raised the bar for other county and city societies to provide research materials and educational events to the interested public. As noted by Gray, “Our ultimate goal is to consign all the written documents on Hancock County history that we can gather into a database that will provide instant access to information being sought.”

“We all learned a great deal from Katrina,” recalled Coleman. The hurricane was a major impetus for increased focus on digitizing.

Over the years, HCHS has received and cataloged thousands of primary (original papers, images, and maps) and secondary (books, annuals, and reproduced images) resources. Cataloguing documents takes a great deal of time. A collection of photographic negatives from Anthony Scafidi, a prolific Bay St. Louis photographer of the late 1940s through the early ’60s, for example, took multiple volunteers an entire year to clean, scan, and print for conservation purposes. Marianne Pluim, volunteer webmaster and computer pro, shared her thoughts on digitizing materials for public access and archival protection. According to Ms. Pluim, having access to cemetery, marriage, divorce, and land records online has made it possible for researchers at a distance to find key elements to their genealogical or historical research. Also, between 125 and 150 people actually visit the HCHS each month for research purposes, and having the digitized materials helps to make research time less lengthy. It also secures these important resources in case of natural disaster. Volunteer Beth Weidlich, like Marianne, is interested in saving a large quantity of materials for posterity. A regular Tuesday volunteer, Beth is deep into a project to scan materials located in the vertical files for uploading. Ana Balka works alongside Weidlich on the resources archive project, and recognizes the importance of history to county residents, but also to newcomers to the area. A transplant herself, Ana sees opportunities to expand our understanding of history in Hancock County by researching for example, the economic ebb and flow of businesses before and after catastrophic weather events, or for deepening our understanding of African American history in the county.

Dot Larroux Kersanac, another volunteer, is working on her own project. She is crusading to gain a Magnolia Marker for Cedar Point, where her family has had a presence for many years. A former teacher and respiratory therapist, her work-in-progress began in October 2015.

The Historical Society is concerned with more than paper documents. The Society and the Bay-Waveland Garden Club work together to register Hancock County’s oldest live oak trees, with volunteer Shawn Prychitko at the helm of those efforts. Read in-depth stories from the Cleaver about live oak registration here and here. Jim Thriffiley, 1st Vice President, is in charge of scheduling the monthly speakers. When asked what qualities a speaker should have, Thriffiley responded, “Warm, receptive, and clever.” Eddie Coleman said that people from many countries and states have contacted the Historical Society for assistance in research or genealogy. Between in-person visitors, telephone calls, and email inquiries, the daily workings and research fill the day for volunteers. The HCHS Board of Directors are all volunteers: Board President is Marco Giardino; Jim Thriffiley is 1st Vice President; Jackie Allain 2nd Vice President; Lana Noonan, Secretary; Georgie Morton, Treasurer. Scott Bagley, Publicity Chairman; John Gibson, Historian; and Ames Kergosien, Member-at-Large. This year on October 31st, the Society will hold its 23rd annual cemetery tour in Cedar Rest Cemetery. According to Gray, the event needs many volunteers every year to be successful: 10-12 to portray historical figures buried in the cemetery, another 10-12 to serve as guides, and several to welcome visitors to the Lobrano house, where guests are invited after the tour. As noted on the Society website, “All talents are welcome. No experience required.” Come join in the fun and help preserve Hancock County history. For more information on volunteering, possible submissions to the newsletter, or research, contact HCHS at 228-467-4090 or hancockcountyhis@bellsouth.net. Epilogue: Life As I Have Known It

Pat Murphy's book-in-progress is no longer a book in progress. In this final installment, he takes the long view back over his own life and some of the people he has known and loved.

Ellsworth's Legacy

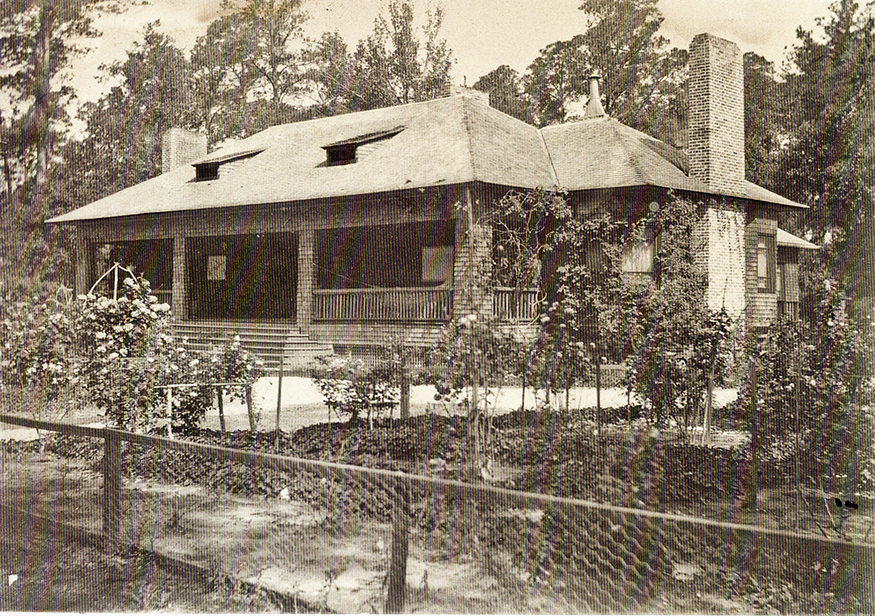

A cherished family home is snatched from the verge of destruction and restored to pay homage to former owner Ellsworth Collins - Bay St. Louis artist, woodworker and musician.

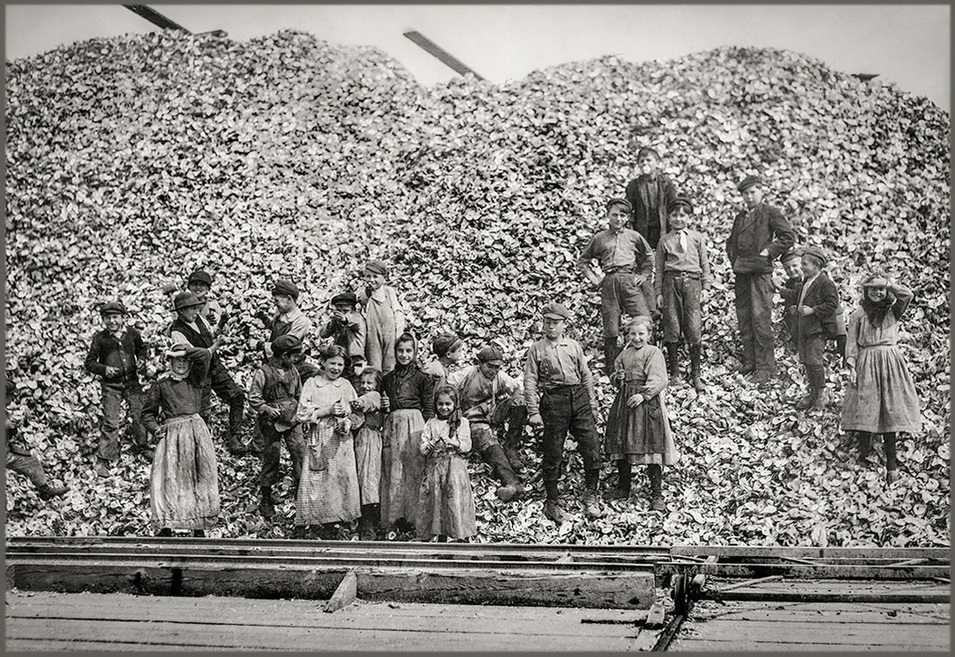

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson Lost Childhoods

A restored collection of historic images by legendary documentary photographer Lewis Hine tells the poignant story of children who worked in the Mississippi coast seafood industry.

- story by Ellis Anderson, photos by Lewis Hine and Joe Tomasovsky

But Sadie is better off than some of the other children Hine has photographed. She is wearing shoes. They’re battered, but they provide some protection from the acid of the shrimp that eats holes in leather soles. Some of her young friends work with bare feet.

The images recall an era when profit was the unabashed king of the country. Compassion for one’s fellow man was the province of church ladies, not serious businessmen. Attempts to establish regulations to protect workers’ lives were scorned by wealthy tycoons. Burdensome bureaucracy and government meddling, they called reform measures. How can we provide jobs if we’re hamstrung by regulations? Some of the cheapest sources of labor were children. No matter the industry or its location in the country, profit margins soared by paying desperate adults starvation wages. They went up even further if the family’s children worked as well. Children were paid a fraction of the pittance the adults earned. They were nimble, too, their small fingers able to perform often-dangerous tasks that adults could not.  Lewis Hine Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine was a teacher so moved by the plight of child workers that he left his job and went to work for the National Child Labor Committee, a private, nonprofit organization founded in 1904. According to the book “Kids At Work” by Russell Freedman, Hine became an investigative photographer in 1908, concocting ruses to get onto jobsites with his camera. It was dangerous work, and he risked beatings and worse to tell the visual story of childhoods lost to greed:

“If people could see for themselves the abuses and injustice of child labor, surely they would demand laws to end those evils. His pictures of sooty-faced boys in coal mines and small girls tending giant machines revealed a shocking reality that most Americans had never seen before.”

Joe Tomasovsky, a retired photography teacher who lives Bay St. Louis, restored digital files of Hine’s original work, which can be found in the Library of Congress. The library contains over 7000 images of children at work that Hine shot during his career.

Joe, who grew up in Gulfport, had taught Hine’s work to his Florida photography students for years before his retirement, but only recently discovered that Hine had taken pictures on the Mississippi coast. He felt the images needed a wider audience and began the restoration project as part of his work with the Mississippi Gulf Coast Museum of Historical Photography (MOHP). According to Joe, the digital files in the Library of Congress are scans of contact prints made from Hine’s original glass 5-by-7-inch negatives. He sifted through the thousands of available images Hine took in his travels to find ones relevant to the Gulf Coast and the seafood industry.

While the quality of the images has suffered from age, poor processing, and repeated duplications, Joe spent hours meticulously restoring each one of the digital files to more accurately reflect the original quality. He then printed the files in large sizes (up to 24 by 38 inches) onto archival canvas, allowing the images to be viewed without a barrier of glass.

“These people that Hine photographed in this series were mostly immigrants,” says Joe. “They were known by the derogatory term ‘shrimp pickers.’ They dressed differently and they couldn’t speak English, but they had an incredible work ethic and earned a lot of respect. Many of their descendants are still here on the coast today.

“Hine believed he could use photography as a political tool to bring about change for these people. He was part of what’s now known as the Progressive Movement.” The George Washington University website defines those early Progressives as “people who believed that the problems society faced (poverty, violence, greed, racism, class warfare) could best be addressed by providing good education, a safe environment, and an efficient workplace… They concentrated on exposing the evils of corporate greed, combating fear of immigrants, and urging Americans to think hard about what democracy meant.” Lewis Hine lived long enough to see his work have a major impact. In 1938, Franklin Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act into law, a federal mandate that prohibited children under 16 from working in manufacturing and mining. Hine died in 1940, before the law was strengthened in 1949 to include other types of jobs. But child labor is still a major issue worldwide today (including in the United States) so the work of Hine continues to be relevant, generations later.

Joe explains how Hine’s final years were spent as a pauper, cut off from financial support for his work by the powerful figures he’d exposed through his photography.

“But no one could diminish the power of his work. This exhibit is a tribute to what one man was able to accomplish using the lens of his camera.” The Bay St. Louis Library plans to host part of the Hine exhibit sometime later in 2016, focusing on images from Bay St. Louis and Pass Christian. Keep on eye on our Upcoming Events page; details will be posted there as soon as they’re available. Grandpa George Stevenson

In this fascinating chapter of Pat Murphy's book-in-progress, he writes about his grandfather, Bay St. Louis citizen and businessman, George Stevenson.

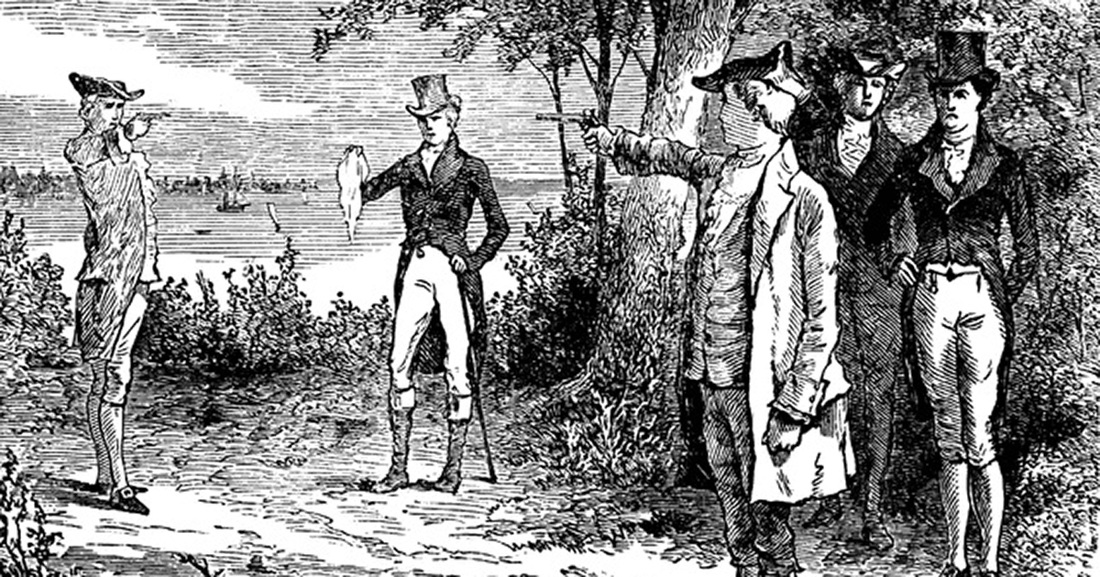

A Matter of Honor in Bay St. Louis

Bay St. Louis in the 1800s was popular as a place for dueling, in addition to relaxing. This fascinating piece details a few of these life-and-death dramas that took place on our coast.

- story by Rebecca Orfila

Soldinie's Grocery - The Center of the Neighborhood

S&B's Bar & Grill on Sears Avenue is located in the original home of Soldinie's Grocery. Grandson Rick reminisces about growing up in an establishment that was the neighborhood's beating heart.

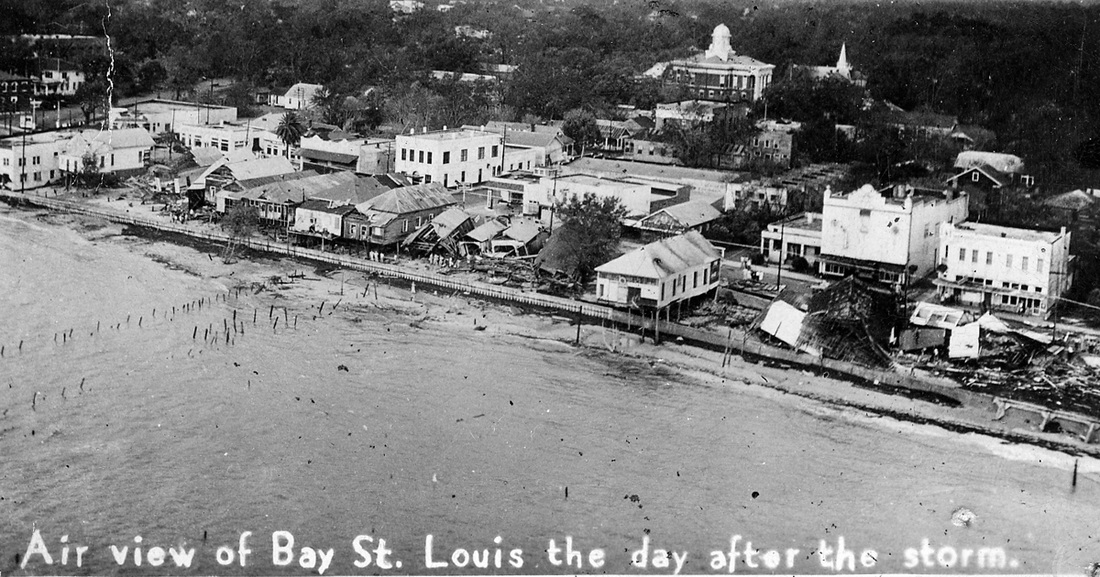

- by Becky Orfila The Hurricanes in My Life

In this chapter of Pat Murphy's book-in-progress, he looks back at the storms that have altered the lives - and the history - of the town.

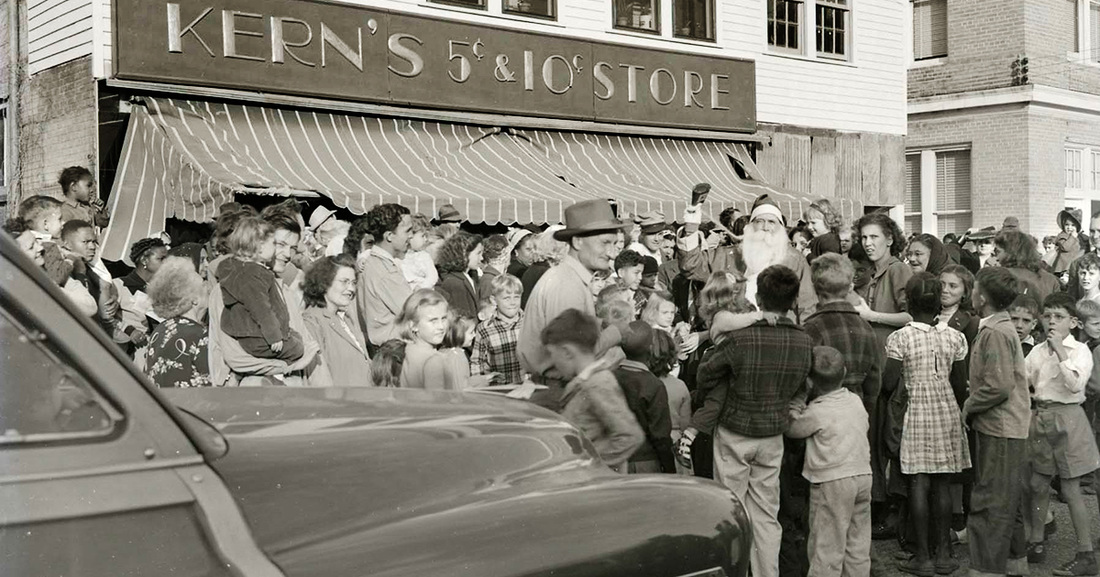

Drug Stores, Praline Shops, Piers and Beaches, Funeral Homes, and Ice House

In this chapter of Pat Murphy's book-in-progress, he leads us around the Bay St. Louis of the past, visiting soda shops, piers and even funeral parlors!

Eve McDonald

Nine decades spent determined to leave the world a better place than she found it shows in the wisdom and the smile of this Bay St. Louis icon.

- story by Pat Saik The Monti Model Museum

An unremarkable office building in Waveland contains an extraordinary collection of more than 4,000 models of planes, ships and cars. Walk in, but be aware your jaw could hit the floor.

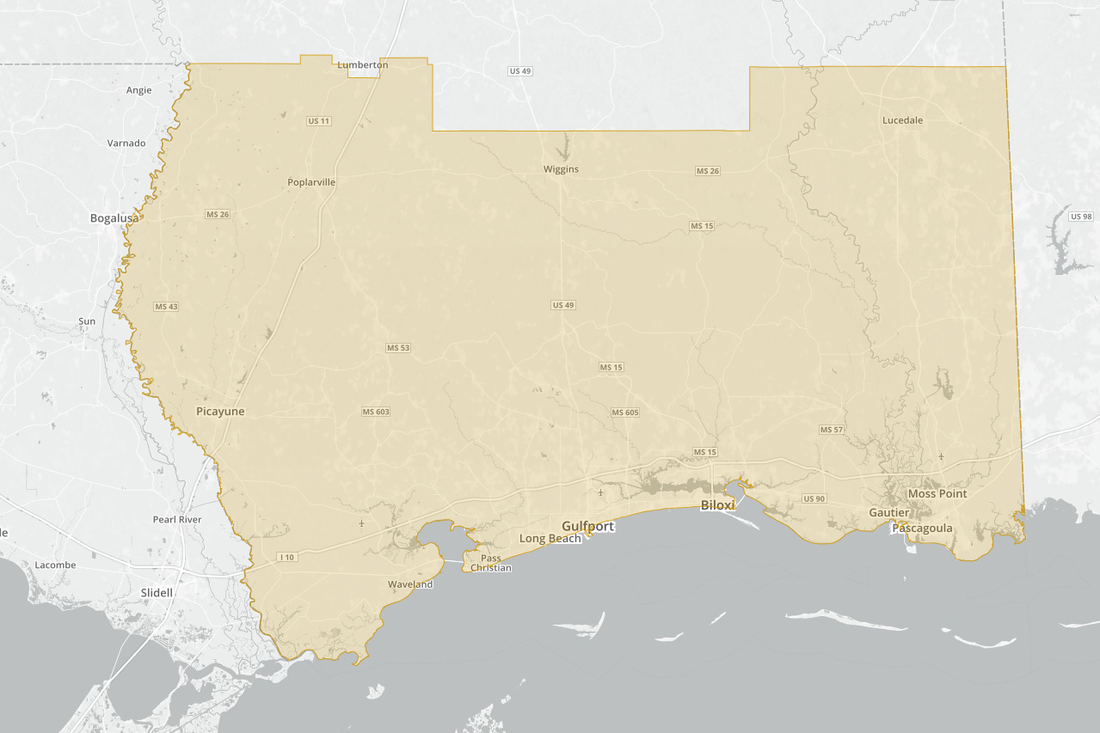

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson The Gulf Coast National Heritage Area

One of the most prestigious designations in the country honoring culture and natural resources recognizes the treasures of the Mississippi Coast. Find out more about the program and how it can help us shine!

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Rebecca Orfila and Ellis Anderson

The Bon Silene Rose The Bon Silene Rose

Heritage areas are congressionally designated regions that connect natural, cultural, and historic resources in order to recognize the diverse nature of our nearby heritage. Currently, 49 Heritage Areas have been established within the national program. Per the National Park Service (NPS), these nationally identified heritage areas are “lived-in landscapes” and not governed by the NPS. Instead, the heritage areas team up with the home communities to focus on local interests and needs.

Local management of the Mississippi Gulf Coast Heritage Area is the job of Department of Marine Resources’ Deputy Director of Coastal Restoration and Resiliency, Rhonda Price and her staff. Price works to facilitate the necessary partnerships of communities, governmental agencies, non-profit organizations, and individuals who value our region's rich cultural diversity, history, traditions, and natural beauty. Among her list of projects for 2016, Price described taking the Bon Silene project a step further with plans to bring back the Bon Silene roses to the property. The property took its name from the carmine-pink flowers that were originally planted on the grounds. In 2015, grants totaling $200,000 were awarded by the Mississippi Gulf Coast Heritage Area to help support diverse initiatives. All of the grant awards will be matched with local or state funding and donated services.

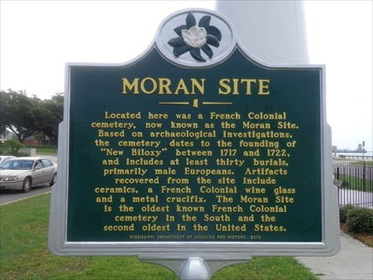

Following Hurricane Camille, foundation repairs of Joe Moran’s art studio in Biloxi uncovered twelve skeletons that were originally identified as Native American. Moran protected the skeletons in situ and went on about his studio work. Hurricane Katrina ultimately destroyed the structure, which allowed for additional excavation and study of the site. This examination resulted in the identification of 20 additional burials. Following osteological study, the remains were identified as French Colonial settlers. The Moran site is now recognized as the second oldest cemetery of French Colonial settlers in the United States.

The remains of the settlers were reburied on site in Biloxi. The reinterment ceremony included a Rite of Committal conducted by Bishop Roger Morin. Also participating were Knights of Columbus from local churches as well as members of the 1699 Society in period garb from Ocean Springs. As with the planned landscaping at Bon Silene, Rhonda Price and her team are finalizing plans for a memorial garden at the burial site of the settlers. Design of the gardens will include evergreens styled in the parterre fashion. Additionally, a life-size sculpture of a weeping angel will be included to honor the colonists and their suffering. Whether for restoration, preservation, access projects, signage, or educational programs, the Department of Marine Resources’ Mississippi Gulf Coast Heritage Area team encourages leaders of our area resources to apply for annual grants. For additional information, click here. Note: The Bon Silene Restoration and Preservation Project was the Recipient of a 2014 Heritage Award for Preservation Education and the Trustees Award for Exemplary Restoration of a Mississippi Landmark. Christmas in Downtown Bay St. Louis Pat Murphy recalls Christmases past and youthful hijinks in this installment of his book-in-progress about historic Bay St. Louis. The Jourdan River School

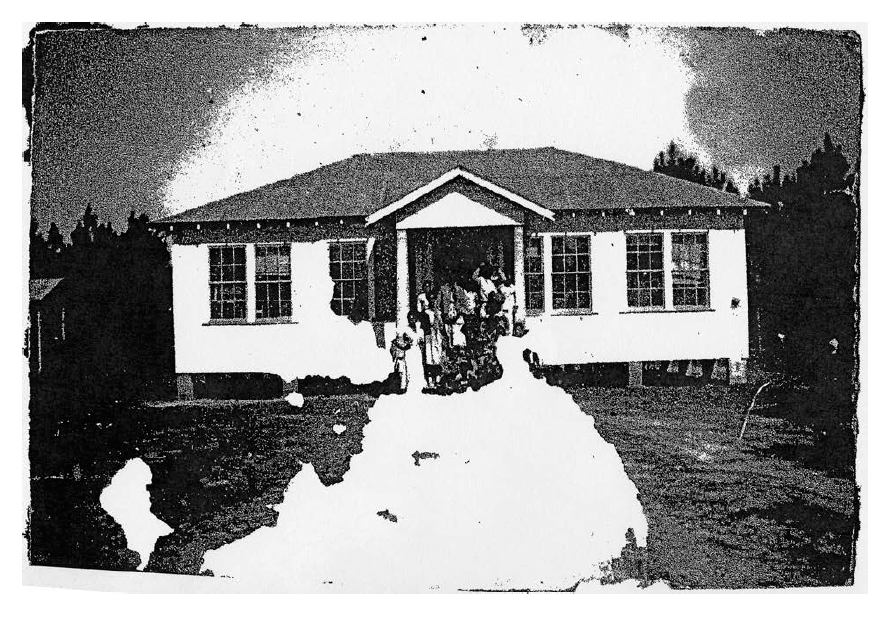

A forgotten Hancock County historic treasure has a chance at a new beginning, thanks to a dynamic young leader and the Mississippi Heritage Trust's "Most Endangered" program.

- by Rebecca Orfila, photos courtesy MHT

On October 22, 2015, the Jourdan River School was added to the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s 2015 Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites in Mississippi, a program that serves to identify and champion the protection and restoration of important historical sites. In a recent press release, the Mississippi Heritage Trust (MHT) reported, “The Jourdan River School is one of few remaining African American schools in south Mississippi.”

As noted by MHT Executive Director Lolly Barnes, “The goal of the ‘10 Most Endangered Historic Places in Mississippi’ program is to raise awareness about the many threats facing our rich architectural heritage. By educating the public about the history of the Jourdan River School, we hope to find the resources to save this special place.” Danin Benoit (operationwakeup@hotmail.com), a representative of Community Wakeup and Men and Women of God Ministry, the nominators of the school to the Most Endangered list, explained that school alumni Earllean Thompson Washington contacted him to advocate saving the old structure. The next step for the Jourdan River School is fundraising.

Community Wakeup and the Men and Women of God Ministry groups intend to raise funds to facilitate the renewal of the Jourdan River School, in addition to potential grant opportunities. Supporters hope to meet with school alumni in February of 2016 to hear their stories of the old school in the trees.

Backed by the enthusiasm of former students, Ruby V. Patterson and Velma Frederick, plus several local groups and individuals, Benoit hopes the school will be brought “back to light” and serve as a community center for the Kiln area. Scenes from the Most Endangered Event on October 22nd

|

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed