The author takes time to study the quietness of the forest and the unique qualities of its inhabitants.

- story by James Inabinet, PhD

Winged blue jays were doing bird-things: eating muscadine berries, building nests in early spring, picking aphids off of stems, and singing songs. Wiggling earthworms were doing earthworm things: tunneling just below the surface of the ground, eating leaves, feeding armadillos, squirming when encountering ants or sunlight.

Hopping frogs were doing frog things: sitting on lily pads, hunting insects, swimming, calling for a mate, and feeding snakes. Crawling fence lizards were doing lizard things: running over the ground, hunting, slipping tongues in and out of their mouths, performing push-ups to show off blue underbellies, feeding birds, digging under leaf mats, and remaining motionless when the shadow of a bird passes over.

Rooted red maples were doing maple things: limbs reaching toward the sun, growing tall in moist bottomlands, flowering and seeding in mid-winter, and feeding squirrels. The initial goal of the investigations was simply to make careful and detailed observations of anything that captured my interest. In the goldenrod field, for instance, I sought the unique character of goldenrod so as to understand its process of becoming, to understand how it became what it is. Not a form frozen in time, goldenrod grows and becomes, changing every day. Through detailed observations I noted how goldenrod expressed itself: basal rosette of fuzzy green leaves, long straight stems, robust yellow fall flowers. In the beginning, all goldenrods looked the same. Over time, the more I looked, the more I began to notice variations. I noticed that goldenrods in the field were usually small in stature, but large in flower while those in the forest tended to be large in stature and small in flower. Further investigations revealed individual differences. No two goldenrods were alike. I was eventually able to detect particulars for each one, a unique and individual character–though detecting that individual character was often difficult. After many forays watching animals, I noticed that after an organism’s needs were met, she would often sit idly, perhaps resting in a protected nook. A coyote near the bayou with a rabbit once panted under the low-lying limbs of wax myrtles. A frog-fed copperhead curled up on the creek bank in the shade of titi limbs. Satiated towhees sat on limbs, either singing or resting quietly. A finch left a bush half-full of berries and never returned - unless she slipped in and out without my noticing. It seemed that nearly all of the organisms I chose for careful study rested when not hunting or hiding or escaping. With no dire call to incessantly hunt and store food, enough seemed to be enough. In these ways and myriad others, I noticed that the characteristics of each organism amalgamated into a unique expression. Deathcaps of the forest floor displayed a unique sense of fungusness unlike that of puffballs. The squirrels of the canopy displayed a unique sense of squirrelness, an identity unexpressed by any other organism. Water oaks displayed a sense of oakness unique to their kind, an expression that I became so familiar with that I could eventually distinguish water oaks from others by gazing at twilight silhouettes from far away. I called each organism’s manner of being its identity. Each organism in the forest possessed a unique identity, unique as species, unique as individuals. The primary inclination of each individual seemed to be to express its unique identity as individual in its forest home. I longed to find out what humanness must be like in my forest home. I longed to find out my identity, to find out what Jamesness must be like if it were to be fully realized.

Our Hancock County philosopher observes the natural world around him acting in harmony and wonders where humans fit in.

- Story by James Inabinet, PhD

Minutes passed. My eyes remained closed as I felt a simple joy at being here, now. My wandering mind soon fell onto why it felt so good and it occurred to me (as it has before) that it might be the interlacing harmony of it all.

A palpable harmony, a felt one, I have quite often found myself to be ensconced here in my forest home within a panoply of seamless fits, a place where everything seemed “just so.” Homes and niches interpenetrate and overlap homes and niches–and I am a part of it! I have surmised that every constituent being, by simply following their desires to be, by just being and doing according to true natures, contributes to and creates this harmony.

Oak trees are being oak. Driven by a desire to be oak (no more-no less) they surge with hormones and produce flowers that become acorns, food for squirrels, birds, and weevils–and budding oak trees.

Weevils are being weevil. Driven by a similar desire, they drill into acorns where eggs are laid that hatch into acorn-eating weevil grubs. Shiny green tiger beetles, driven by a desire to be and do tiger beetle, are running about–fast–on the forest floor to catch and eat small insects, notably acorn weevils. Lizards are there too, among the beetles, prompted by desire to just be lizard. Some are flashing blue underbellies while others flash ruddy neck extensions, even as tiny flying moths are snatched up and devoured. Bees, driven by a desire to be bee, can be heard buzzing about (a totally bee behavior), checking-in on coreopsis flowers over there, wild plum flowers over here, and huckleberry flowers over there. Sitting on a mat of leaves, I leaned against a water oak to gaze. A barely visible dogwood bloomed through intervening foliage. I listened to the gentle breeze in the canopy and scanned. A low-flying pine warbler, lured by desire to be warbler, flitted from limb to limb. She was singing a distinctive “warbling cheep” while jerking her head about rapidly, side-to-side, up-then down, jerky–nothing smooth about it. To the west about a hundred feet away a male swallowtail, driven by desire, perhaps by the proximal scent of a potential mate, flew haphazardly but quickly from left to right and out of sight, two hundred feet in a matter of seconds.

In the face of a desire to be and the apparent harmony within my forest home, I wondered about humans. I wondered about human-in-harmony, about what it might be like for a human being to live in harmony with the forest in the same way an oak or a warbler or a fence lizard lives in harmony.

What would that be like? What would it feel like for a human in service to a potential “human niche” to perform a “human function” that creates it? Ecologically, an organism performing its function in an ecosystem is performing its niche. Niche is kind of like a “job” in the ecosystem, both the place and the functioning, inseparably, together, including associates, i.e., oaks and weevils and squirrels and warblers. Squirrels perform a squirrel function by gathering acorns, ripping pine cones apart, running along limbs, hiding from the cooper’s hawk behind a pine trunk. By performing these functions, a squirrel niche is performed. How does the squirrel know what to do? She follows instinct for sure, but what is that like? I surmise that niching behaviors are prompted by a desire to be and become, whatever kind of organism is in question. Squirrels, driven by the instinctual desire to BE squirrel, perform niching behaviors and squirrel niches spontaneously spring into being. This brings us back to humans and niche. In a forest ecosystem, what might a human function be? Along the lines of squirrel function and niche, this must be a performance of human function that brings about a human niche. How would a human know what to do? Is it just instinct? In its performance, would human niching harmonize with the functioning of other beings of a forest like squirrel functioning does? What would such a human niche look like, be like? More importantly perhaps, what would it feel like? These questions haunt me.

“Our first teachers are our feet, our hands, and our eyes. To substitute books for all these is but to teach us to use the reason of others." Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Story by James Inabinet, PhD

Somehow, though, we are comfortable with these conflicting views. Trouble begins, I think, when we privilege what we think and know from books or screens at the expense of experience. Ordinary third-graders are now expected to learn about trees by reading about them or by gazing at photographs in a book or computer. Effectively removed from actual trees, these students come to know them devoid of sensual experience, without ever looking closely, without feeling the difference in texture between magnolia and beautyberry leaves, without smelling the difference between crushed bayberry and red bay leaves, without smelling the root beer scent of sassafras roots. Inside sterile rooms these students sit with their books, bored to death, engaged not in their own reason, but in Rousseau’s “reason of others.” In many ways the whole of modern culture has given over experience in favor of thinking. We have learned more from books about how trees grow and make leaves and feed squirrels and birds and bugs than we know about the tree in our front yard – if we even have one anymore [it might fall on my house in a storm].

Oh, but the living green world that I see outside my forest home is more vivid than any words can convey. I wonder how much we have given up sitting in classrooms, looking at books, staring at screens? Nature beckons me; it calls me home, to the direct experience of moving suns. The natural world is directly experienced with a body first – feet, hands and eyes – the initial basis for any knowledge. I am sitting here at the edge of the forest looking at a red bay, its lance-shaped leaves deformed by galls; crossing branches hold a squirrel nest; a bevy of pines loom behind it. No book can tell me this, no screen can convey the whole of it; the smell of the leaves – try to describe that. In these ways and myriad others, a body first comes to know a tree tacitly. Tacit means silent, without recourse to words or why or how. Tacit knowing is like typing. If we think, we can no longer do it. We experience the world first with our bodies: feet, hands, and eyes. The very act of living in a body necessitates experience — that’s what it’s there for! In this way, my body is more a means for communion with the world than a boundary that separates.

So, what does the world of hands, feet, and eyes actually tell me? From far above I might experience the earth as kind of flat. Were I to gaze down like a soaring eagle, I might see brown and green earth, blue Gulf. I might see a bay-side city-scape dotted with houses, painted-on like a pointillist might put onto canvas. This flat circle earth is a mandala world of rich color-in-motion. The winds of the four directions nourish me as I soar at its center. The morning sun on this stationary earth rises everyday without fail, arcs steadily overhead, and finally sets late in the afternoon. This moving sun is our experience, based on the inner workings of a life-world that’s actually lived. The very concept of motion, of rest, of time, of space, is derived from Earth, is relative to Earth. I can watch the dome of the sky on any night turn around Polaris until the light of the sun obliterates the view. I can feel its movement as Orion descends below the horizon and Cassiopeia moves upward into view. Experience is the birthplace of meaning. A nameless aborigine said: “Whatever one sees is a reflection of oneself.” What kind of reflection does a disembodied mind see? What meaning is derived? Is that what we want… or does it leave us hungry? He continues, “this is not taught in schools; this is what the cuckoo taught me on the cliffs of Cornwall.”

In this series, local naturalist and Zen explorer, James Inabinet, experiments with ways to consider the world from another living creature's perspective - and discovers a new way of seeing.

- by James Inabinet, PhD

Keen far-sightedness might be another. From an elevated perch, the hawk detects subtle movements in the field that betokens the presence of tiny beings, like the vibrations of a blade of grass– not rhythmic, wind-produced vibrations but the unique, irregular movements of grass blades that could only result from a moving living being.

Other gifts might be sharp, strong gripping claws that can grab a mouse or snake off the ground on the fly. These and other potentialities are brought into the world and made manifest when hawks simply go about hawking, by hawk-doing.

All hawks do not manifest these potentialities identically. Each individual hawk possesses a unique potentiality to manifest hawk gifts. One hawk may possess more patience and decide to perch longer than another – and get a meal because of it. Another hawk may be able to see better than another or have sharper or stronger claws. All hawks exhibit hawkness equally, but each according to individual potentialities.

I tried to imagine what I would see from the hawk perch. Viewing the field from that distance, I might see it more in its wholeness than a mouse does. The mouse is so close that all she sees is field parts, her nose touching everything she sees.

The distant hawk cannot see in this way; he might see the bird and not wings, claws, or beak, or the mouse and not legs, ears, or eyes, or the field itself and not goldenrods, fleabanes, or bluestems. Seeing in a hawk way, effectively removed from individual plants, I would not know them. As I sit, I can easily imagine myself soaring above the land looking down, but the imagery seems ephemeral, not so easy to produce and even harder to hold onto.

After a minute my mind begins to wander with thoughts of home. I sit with closed-eyes in silent meditation for a few minutes, thinking of nothing, and try to return to the soaring above.

As I wonder what I see, I try to feel it as much as see it. I become increasingly immersed in the process; more complex images form; the imagery becomes easier to produce and hold. As I lose the sense of myself, I begin to imagine tree tops, pines, oaks, and magnolias, as splotches of color, mostly varied hues of green, but tinged with brown, red, and yellow here and there – it’s fall after all. Panning around, I can see the snaking creek, mostly obscured by trees, but splotches of dirty white tell of sandy embankments along its edge. Sunlight catches on ripples reflecting brightly in the shape of asterisks [!]. The image is so real that I mentally blink under the intensity of the light. After a while of sitting in this way, I am abruptly pulled from the reverie of soaring by the laugh of a pileated woodpecker just out of sight off to the southwest. It took a second or so to get my bearings. I remain fascinated for a moment by the flashing images of reflected sunlight on creek ripples. I begin to consider, again, what the hawk might see, flying high above the land over the goldenrod field. Of course, he sees the whole field. Panning farther back and away, higher and higher, what does he see? He sees La Terre! ... but not in any normal way. Seeing trees from high above is an unusual way for humans to see trees. To make sense of the mishmash splotches of color, the participant must think. Seeing wholes requires imagination. The participant imagines how color splotches are related to each other, how they connect to produce a recognizable form of order: “tree-top-wholes.” To imaginatively step back further is to go beyond color splotches and consider how trees and bushes are related, how they are connected to become forest wholes, swamp wholes, meadow wholes. The preoccupation of hawk-knowing is not things but relationships. As the soaring hawk ascends higher and higher above La Terre, he sees more and more of the surrounding land. Horizons crop the view in all directions to make a mandala: the Mandala of Hawk-Knowing. As the hawk soars ever higher, this circle of seeing expands to include much of the Dedeaux community. From higher still, the mandala expands to eventually include the entire Gulf Coast, the entire southeast, and ultimately the entire globe as horizons extend in all directions.

A local naturalist and zen explorer experiments with ways to consider the world from another living creature's perspective - and discovers a new way of seeing.

- by James Inabinet, PhD, illustrations by Margaret Inabinet

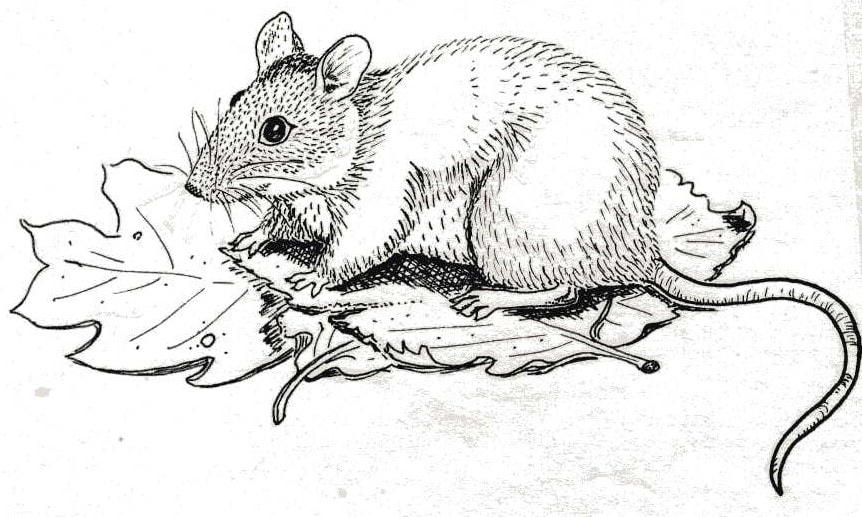

Mouse-seeing is an innocent way of seeing that begins with an empty mind, a “beginner’s mind,” one open to anything as Zen master Suzuki describes: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.”

To begin mouse-seeing, thinking is suspended through meditation or prayer. A quieted mind allows the “seer” to become more mindful of what’s happening right now, right here. With an empty mind one becomes like a hollow bone, ready to be filled with possibility. Several years ago, I ritually began my first journey into mouse-seeing in the goldenrod field. After sitting in meditation for a while, I dropped down and put my nose close to the ground like a mouse to see the field up close the way she would. I could see thickets of grass and goldenrod stems. With lowered head, I crawled for a while seeking mouse roads below the grass and goldenrod “canopy” and experience being in mouse habitat as I moved mouse-like through the field. After a half hour or so, I became bored and noticed that I had been thinking about home and work. I meditated and began again. Soon I stumbled onto what appeared to be a tiny trail. I slid onto my belly to look closer and discovered a mouse trail, a round hole through grass “trunks.” Opening back into the grass, the trail disappeared in shadow. Perhaps a tiny nest was back in there but I would never know. To get close enough to gaze at it would certainly destroy it.

I turned away and crawled towards the early sun. It struck me that humans are upright strangers that blithely walk through woods and fields as hawks, seeing from afar, from on high. We rarely see a mouse or even her signs and yet mice are legion, numbering in the thousands in this place alone. There on mouse roads they run, doing the doings of mice everyday unnoticed until someone gets down on her belly and looks with mouse eyes. Only then can mice and their way of being truly begin to exist for us.

As infants, we once possessed unmitigated body-knowing, as innocent as a mouse on her mouse-road – I only have to remember how to do it. Maybe I can return somehow to an infant’s sense of wonder, alert and curious – like a mouse. Intimate with her world, she sees clearly only what is right in front of her feeling, smelling nose. I moved closer to the stems of the grasses and goldenrods; I touched them with my face, feeling their roughness. Nose to the ground, I smelled the dark, damp earth where it was exposed. I listened closely while simultaneously smelling, feeling, looking. The mouse way is a doing way.

Energetically, I moved through the field, stopping only for brief moments. I alternately blurred my vision and then focused. In blurring, movement can be detected, vital in a mouse world that includes hawk shadows and snakes. With blurred images, one feels more than sees. Blurring interdicts thinking.

With closed eyes I laid down and focused on feelings. A surprisingly rough grass stem was touching my face. I tried to move into that feeling of roughness–without thinking. Moving my face to the side, I felt the mat of dry grass that covered the bare earth, again focusing on feelings. Moving forward a few inches I felt a grass stem on my forehead, focusing on feelings even as an image appeared, an image of what that grass might look like. I continued in this way for about an hour and had moved only about six feet. At the end of this experiment into mouse-seeing, I knew that particular feelings had arisen in me about the nature of the beings of the field, but I could not clearly recall them. It occurred to me that by purposefully suspending thinking, these feelings could not easily become thought and/or words. Something, though, was felt, something known, but I could not say exactly what it was. Even so, my relationship with this place deepened.

Crossing paths - and then following - a snake hunting dinner in the woods sparks a contemplation on how humans can relate to other beings in our world.

- by James Inabinet, PhD

The immovables joined in; scale insects covered moist, succulent stems: goldenrod, asters, Joe-Pye weed. Spittlebugs ensconced below; basal leaves pushed back revealed frothy hide-outs. Cocoons were packed snugly inside rolled-up leaves or dangled under them.

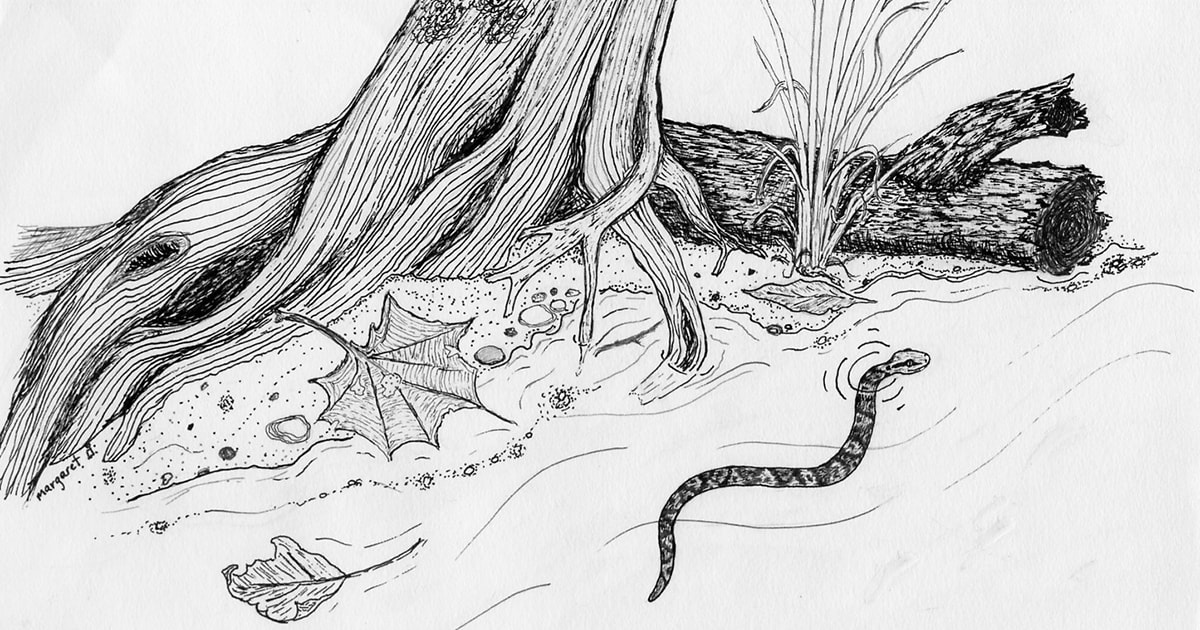

A golden silk spider web blocked the way, a micrathena orb-web right behind it, a spiny-orb weaver web next - signs of late summer. Contorting my body, I went under them. I made my way down the bluff overlooking the creek. Barefoot, I sloshed downstream on the sandy bottom; water just covered my ankles. The roar of cicadas drowned out the rippling water as I approached the confluence of bayou and creek through a tunnel of overhanging limbs and branches. A clearing signaled my approach to the bayou ahead. Movement along the bank next to the trunk of a smilax covered gallberry at the water’s edge revealed a slithering water moccasin. The poisonous snake wended his way into the bayou, hugging the edge. I followed – at a distance. Excited, I watched him slither, weaving back and forth, and then suddenly stop. Motionless except for a wagging tail, he steadied himself, apparently watching something. He remained this way for a long time, several minutes (!), and then struck blindingly fast. A frog jumped to safety, disappearing near the edge while the snake frantically searched. After a minute or so the snake resumed his journey downstream. It occurred to me that this must be the dance of a snake. I followed him, wondering what it might be like to be a snake and slither in the water in this way.

Later, I thought about: “What is it Like to be a Bat?” an essay by the cognitive scientist Thomas Nagel who famously wondered about the consciousness of creatures like bats, forms of consciousness very different from that of humans.

He surmised that there must be “something it is like” to be that organism. In order to determine “what it’s like” to be another being, humans use human points of view by imagining the other to have experiences that are similar to their own. Bats experience the world through sonar, a mode of experience profoundly unlike anything in human experience. Nagel found no reason to believe that batness is like anything “we can experience or imagine.” Concluding his thought experiment, he declared that there is simply no way to know what it is like to be a bat. I presume that knowing what it’s like to be a snake to be no different. Should I forget about the snake? This question cuts to the core of my research of the past 25 years, which is to come to know a forest ecosystem and its inhabitants deeply, even mystically, like a forest monk. The goal: to become a functioning human component within in an ecosystem, a functioning part of its wholeness - to fit in - like our snake or a bat or even a tree for that matter.

If Mr. Nagel remains distant from nature, sitting in his ivory tower armchair watching bats circle a streetlight through a window, he will never know batness and will conclude that no one else can. He could never experience a forest in the way I am seeking.

Because consciousness is subjective, all about me, the experience I have of another being, even a human one, remains difficult to describe. How can someone get to know “what it’s like” for another being? To know “what it’s like” there must be elements of experience where the one is like that of the other. There must be elements of experience we both hold in common. This is what empathy is – feeling the experience of the other. I tear up when you cry because I feel it. Nagel seems to reduce experience to thinking; indeed, he seems to elevate thinking to the order of actual experience wherein what passes for knowledge arises from thinking alone. To look at experience this way is to impose a purely “mental” form of consciousness onto humanity, leaving only a shell of experience. “Thinking” about bats becomes the only way to know about batness at all. You don’t even have to go outside and watch them. Of course, experience itself is always richer than thinking and speaking about it. Thinking about my love, for example, is one thing, but getting a hug from her is so much better. I propose that there are other valid, more experiential, ways of knowing than Nagel’s mental knowing. I propose that “body-knowing” is one of those ways. We have all felt parts of our bodies tightening up or relaxing in the face of profound experience, like the feeling of dread in a place that feels “off.” With body-knowing we know something even though we cannot say what we know - and no amount of thinking can help us to tell. Another way of knowing that I propose is what I call “heart knowing.” It’s a profoundly feeling-oriented, emotional, and empathetic way of knowing, not unlike feeling love for a partner. I have found that you can actually look at and dwell-within another being - even a non-human being - in this manner. If there is any way for humans to experience snakeness, it would seem to require one or both of these other ways of knowing. I am paraphrasing the philosopher Bruno Snell when I add that perhaps a human might never be able to experience a snake or a bat in a “human” way if she did not first experience herself - a human being[!] - in a “snake” or “bat” way. For experience to rise to that level requires more than just thinking about snakes or bats. Following Snell’s ambitious challenge, I have become determined to try a more embodied path to the experience of snakeness and see where that may lead. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed