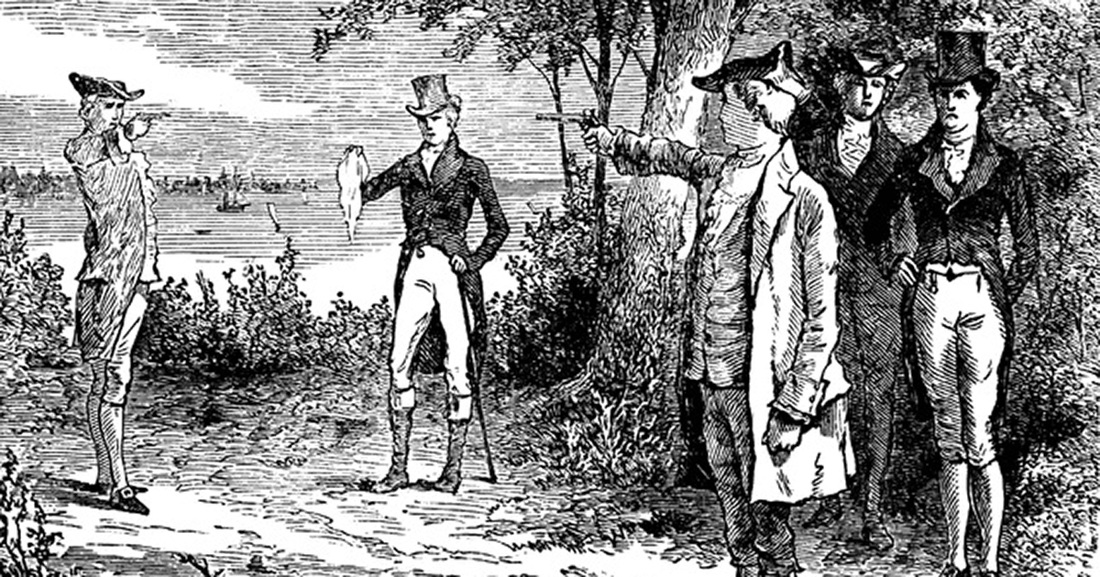

A Matter of Honor in Bay St. Louis

Bay St. Louis in the 1800s was popular as a place for dueling, in addition to relaxing. This fascinating piece details a few of these life-and-death dramas that took place on our coast.

- story by Rebecca Orfila

Before leaving the courthouse, Mrs. Bienvenue verbally accosted Mr. Phillips for what she felt was a defiance of her importance in society. Mr. Bienvenue intervened. Angry at the vocal attack from the lady, Phillips “knocked him down” and Bienvenue set to meet the former’s disrespect on the dueling grounds. As described by a Macon, Georgia, newspaper writer (Y. M. C.), “It is terrible to have a foolish, fashionable, fast wife.” The “fashionable” wife was mistress of her own fortune.

Seconds and physicians were selected and news reporters were informed of the coming engagement of honor. At the strike of the noon hour on April 4th, forty paces were taken and shots fired from double barrel shotguns. Bienvenue took the fatal shot and died immediately. Phillips was unhurt. Prompt coverage by the newsmen present allowed the matter to be reported the very next day in the local and regional papers. Bienvenue was mourned by his family and friends and buried in St. Louis #1 cemetery in New Orleans. Laws regarding duels were addressed during the French and Spanish control of our area. According to Hémard (2014), Bienville forbade dueling in 1725, three years following the founding of New Orleans. The law was rarely enforced since dueling was considered to be a respectable defense of one’s honor. By 1855, the law grew teeth and conflicts moved from the dueling oaks of New Orleans to environs in Hancock and Harrison counties of Mississippi. Mississippi’s laws concerning dueling are first mentioned in the 1832 state constitution where dueling was defined as the fight itself, the individuals involved, and their supporters. Dueling by “any rifle, shotgun, sword, sword-cane, pistol, dirk, bowie-knife, dirk-knife, or any other deadly weapon” was strictly forbidden. Seconds and physicians would be fined a sizeable sum and be imprisoned for three months. If a duelist was killed, the offending man would be arrested and tried on grounds of murder. As romantic as it might seem, the white sand beaches and mossy oak trees of Hancock County were not the preferred choice for combat. The sands, the duelists’ seconds warned, could give way underfoot at the height of the action and provide the opposition with important leverage. Instead, duels took place near the train stations on the plains west of town. These minimally wooded areas of spare grass and small trees provided an unencumbered terrain for a steady shot.

An unusually large number of duels originating in New Orleans involved newspapermen. One well-known conflict was the 1873 duel involving retired judge William H. Cooley and R. Barnwell Rhett, Jr., the editor of the Picayune. Rhett had faulted the Judge in print over a case that ended negatively for the newspaper. Cooley responded with a statement that implied that the Picayune editors were politically motivated.

The duel took place near Montgomery Station. Cooley was a portly man with an infected foot. In constant pain, Cooley was physically unprepared for the challenge of the duel before him. At 10:30 am, the men took their places, paced approximately 40 yards. According to one report, after the first shots were delivered, the exhausted but unhurt Cooley sat down in a nearby chair. The seconds demanded a second volley, and with that Judge Cooley collapsed onto the ground and died from a shot to the heart. His body was transported back to New Orleans in the baggage car of the returning train. Not all of the Bay St. Louis duels ended in death. The duel between Wallace Wood and J. A. Bachemin took place under cloudy skies, a northeast to northwest wind and the threat of light rain on April 18, 1874. Per the “Star of Pascagoula,” the fight had been a long while coming. The two men publicly derided one another in speech and “spicy cards” denouncing one another’s character and morals. The two parties got off at Toulme Station. At a distance of 12 paces, Bachemin and Wood took aim at each other with dueling pistols and fired. Bachemin was wounded, but Wood survived unscathed. Peace was secured. The matter settled and Bachemin’s wound determined as nonfatal, the parties enthusiastically discussed and secured lunch, which was shared on the field of battle. The pleasantries of dining together faded when all involved were arrested on their way back to New Orleans. The arrest for violation of Mississippi’s dueling law was made by a local sheriff at Montgomery Station. Public duels in and around Bay St. Louis faded over time. The rigorous efforts of county lawmen made it difficult for the tradition to continue. Common dueling grounds were taken over by homes and streets. For others, threats to an individual’s honor were replaced by lawsuits, or social and political maneuvering. Many more duels took place in the Bay St. Louis and Waveland area than noted here. For additional information, visit the Hancock County Historical Society for research materials. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed