What is reality if not perception? Is our perception of something the reality, or does it differ from person to person? Dr. Inabinet takes us on a journey between reality and imagination.

- by James Inabinet

This is the final written installment of a larger project focusing on art within place. As the culmination of this project, several local artists were asked to create art from nature and exhibit their pieces at the Magnolia Bayou Art Project, taking place at 100 Men Hall on March 23, 2024.

- by James Inabinet

In this age of man-made barriers to keep nature out of our lives, what if we tried listening to the needs of the land and its creatures?

- by James Inabinet, Ph. D.

Hancock County’s naturalist philosopher considers whether the built environment can have a life of its own.

- by James Inabinet, PhD.

If one could find “itness” in a forest and in a field, could one find it in the heart of the French Quarter in New Orleans?

- by James Inabinet

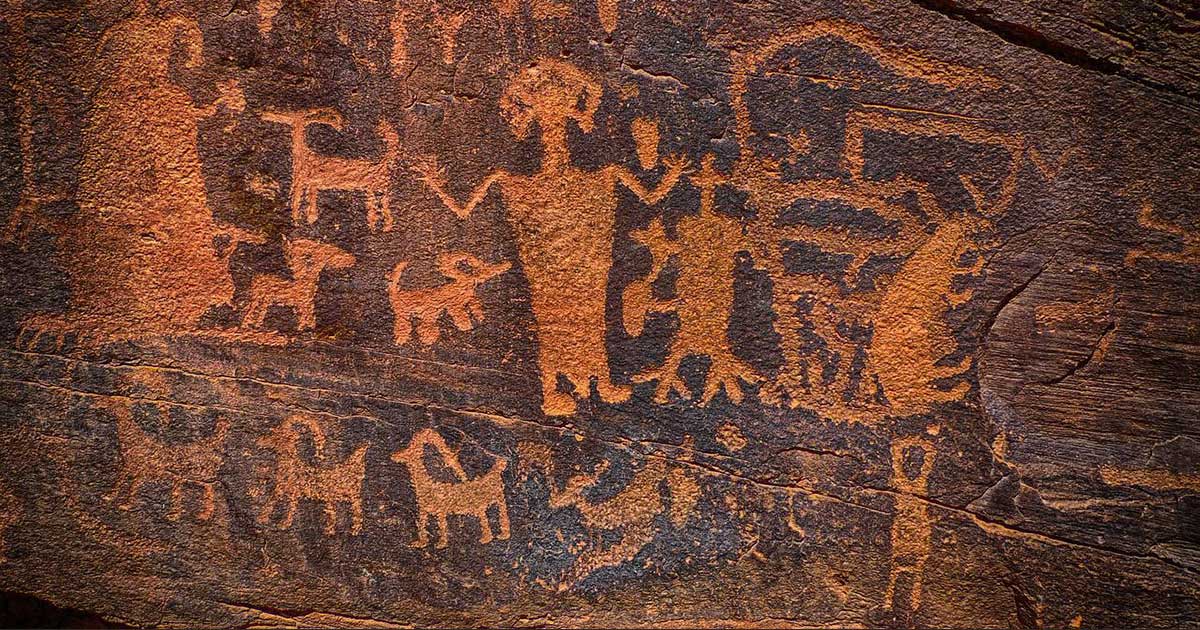

Hancock County’s naturalist and philosopher takes a look at the different stages of the creative process, from experience to expression.

- by James Inabinet

Local naturalist and philosopher James Inabinet explores the inspiration nature’s glories bring to our everyday lives and to our art.

by James Inabinet, PhD.

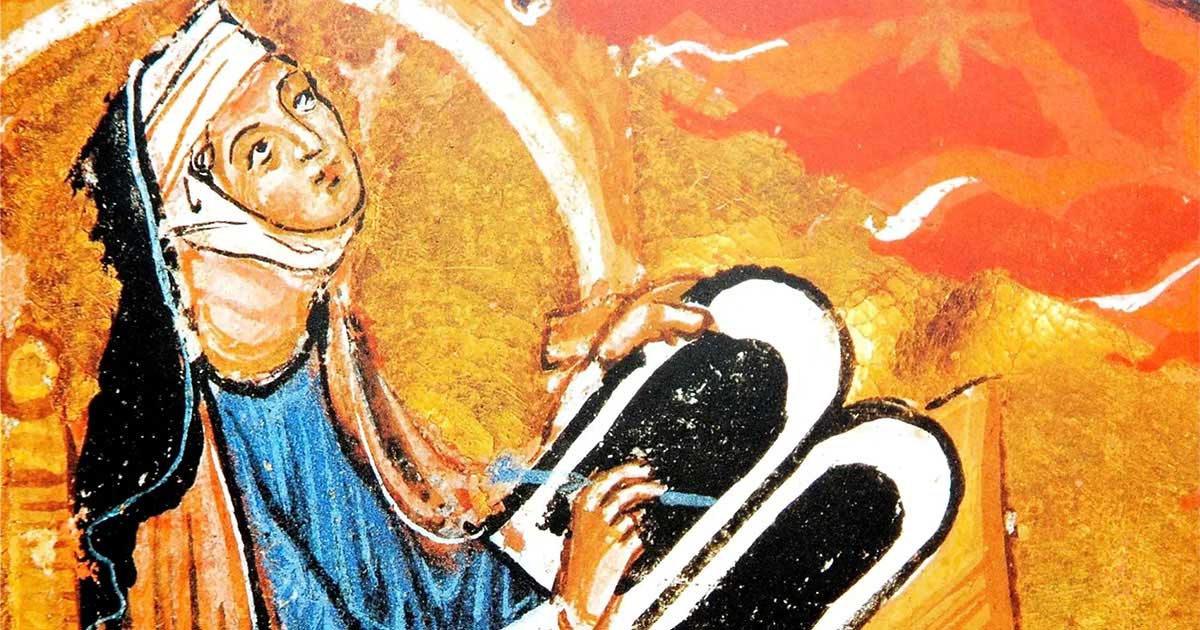

Inspired by the writings of an extraordinary 12th century abbess, Hildegard Von Bingen, our local philosopher and naturalist celebrates the spring season.

- by James Inabinet, PhD

The author takes the time to study his world in a way few of us do – slowly, deliberately, one vignette at a time. Today he considers goldenrod, both as part of something greater and as a world unto itself.

- by James Inabinet

The author contemplates the meaning of the year gone by in a unique way that allows his mind to open to the new year’s possibilities.

- by James Inabinet

We tend to think of the world as made up of two separate spheres – man-made and natural. But is that reality, or merely our perception? Our own Hancock County philosopher weighs in.

– by James Inabinet

Is the forest in a constant state of change? Or is it resolutely unchanging? The author looks at both sides of the debate, with the help from all his senses and guidance from several Greek philosophers.

- by James Inabinet

Humans today do not have a place in wild nature. To re-establish that connection takes purposeful observation and the will to wait. That place will become evident - in time.

by James Inabinet

The author attempts to connect to his identity as an organism in the universe by viewing the world through the eyes of other creatures.

- Story by James Inabinet

Three days fasting in the woods helps the author reckon with a difficult year and find his authentic self.

- Story by James Inabinet

Our own Hancock County philosopher and naturalist looks back on a youthful epiphany that changed the course of his life.

- Story by James Inabinet, PhD

Exploring unmanaged natural areas rather than the groomed trails of "nature centers" requires the explorer to pay attention to his surroundings.

-story and photos by James Inabinet

By establishing an emotional connection, the land and the home can – and perhaps should – become not just a location, but a member of the family.

- Story by James Inabinet

Like the wind, passion can be soothing and persuasive - or relentless and destructive.

- Story by James Inabinet |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed