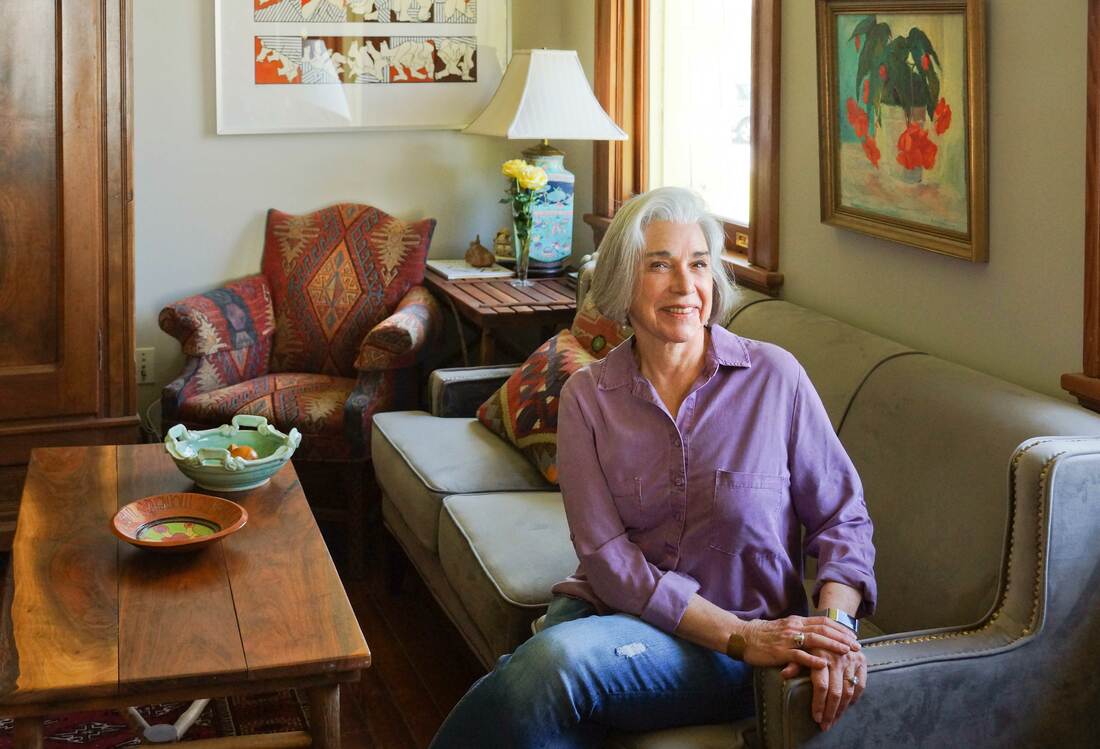

One of the most distinctive houses in Bay St. Louis has been renovated by and serves as home to a lifelong artist.

- story and photographs by Ellis Anderson

Both her sisters and one son (local attorney and Shoofly Magazine history writer,Edward Gibson) are long-time residents of the Bay. A second son lives in New Orleans. Eventually, the pull of family and the relaxed lifestyle had the life-long Jackson resident shopping for a permanent coast home.

Kit and sister Marilyn Mestayer often walked miles together through the Bay’s historic district – the conversation and their scenic routes made the exercise fun. Their path sometimes led down Washington Street where the two always admired the wood and stone cottage near the beach.

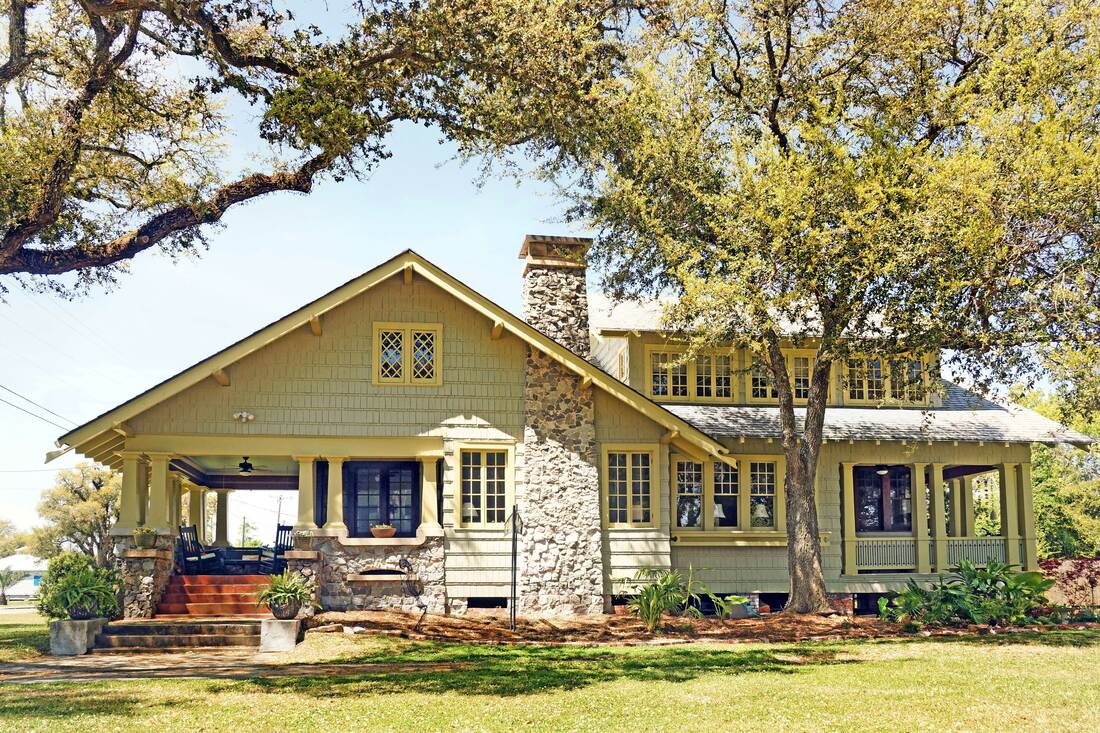

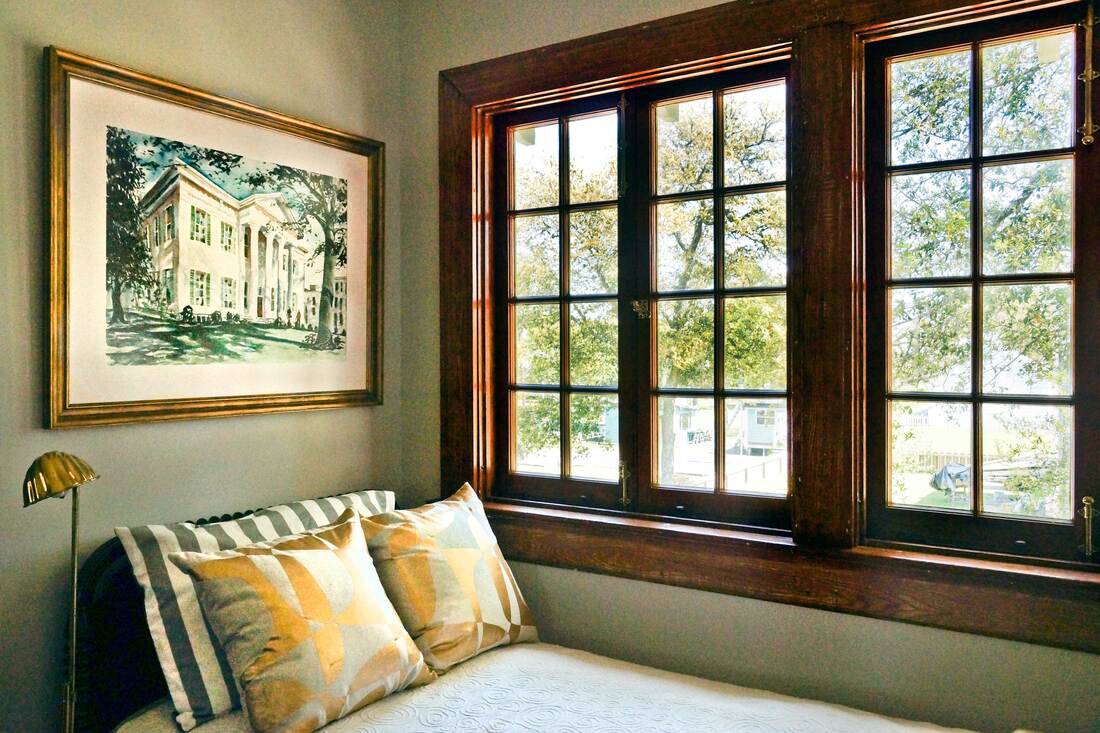

The design itself is a standout on the coast. While Craftsman homes (mostly built from the 1890s through the 1930s) aren’t that unusual – few were constructed using stone, a material that had to be imported from hillier regions. The stout porch columns over the stone foundation give the building a sense of permanence. Indeed, the house, built in 1909, was one of only two on the block to survive Hurricane Katrina. Yet, the home’s many windows provide a lovely counter-balance, welcoming both light and air. One day in 2016, Marilyn called Kit who was visiting in the Bay and excitedly shared the news that 119 Washington was going on the market. Both knew it would sell within hours because of its unusual design. Their prediction was correct. By the end of that day, Kit had a contract to buy it, despite the fact that it needed major renovation.

There were the obvious issues. For instance, kitchen ceiling had collapsed, although it appeared that the sinker-cypress cabinets had survived. An inspection revealed more problems – including the fact that none of the sinks were hooked up to the city’s sewage system. Although there were no active termites, a lot of older termite damage would need to be addressed. But to Kit, the cottage’s charms far outweighed its problems. It’d been built as part of a family compound for the Edwards, owners of a local lumber mill. The larger house next door was constructed for the father, the Craftsman cottage for his son. The family milled all the lumber for both houses, presumably hand-picking the best wood available. Heart pine from now extinct old-growth forests went into the main body of the cottage. For siding, they used cedar shingles.

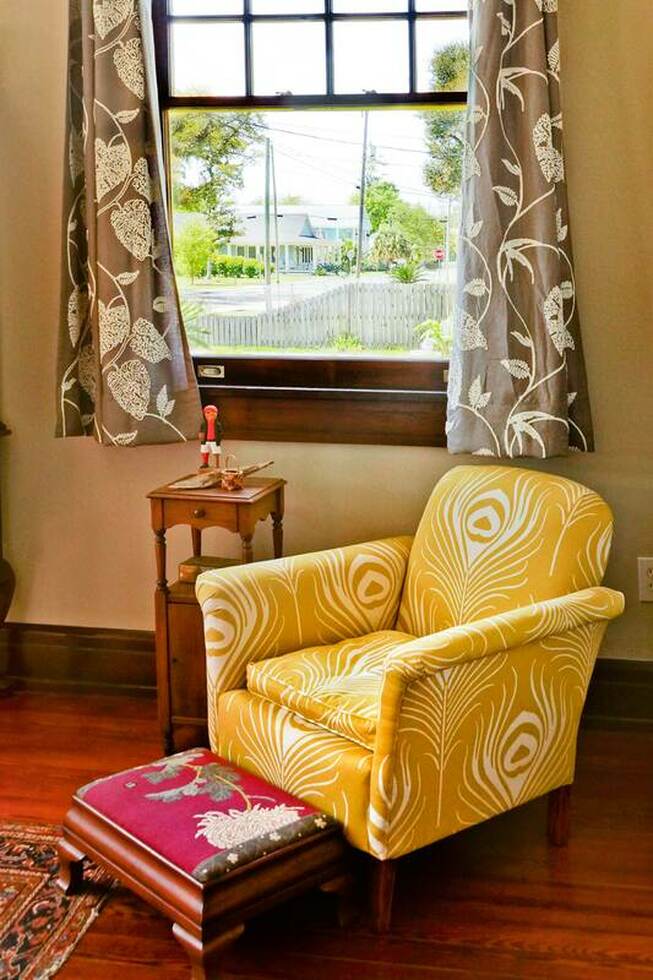

Inside, most of the original woodwork trim – and there’s lots of it – has been left natural. Except in one room. Kit explains that although the dark woodwork trim, windows, cabinetry and doors in the house grace the rooms with an understated elegance, it also darkens the interior spaces – despite the many windows. The dining room at the heart of the house, visible even as one enters the front door, contained ceiling and wall trim in addition, making it something of a “black hole” at the heart of the house. Kit had considered painting all the wood in the house to lighten the ponderous feeling, but first consulted with local interior designer, Al Lawson, of Lawson Studio. Al pointed out that painting only the millwork in the dining room would achieve the effect she was looking for. Kit followed his advice. “It made all the difference,” she says. “Al made a follower out of me.”

Extensive repairs had to be made on the exterior before painting – which required the use of tall bucket trucks to replace some of the eaves.

She tackled the restoration of interior woodwork herself, without striving for absolute perfection in the upper story. “We sort of did the woodwork there the French way – letting it sparkle as it is,” Kit explains, smiling. “It’d be a shame to come into an old house like this and try to make everything perfect. I like that it’s flawed – just like me.” DownstairsUpstairs

Kit had planned to move into the house while the work was being completed. But one day while she was painting upstairs, water started pouring through the ceiling. It turned out that the old HVAC system couldn’t handle the load. She counted herself fortunate that she’d been on site or she would have been dealing with another collapsed ceiling. Two new HVAC systems had to be installed, along with additional insulation.

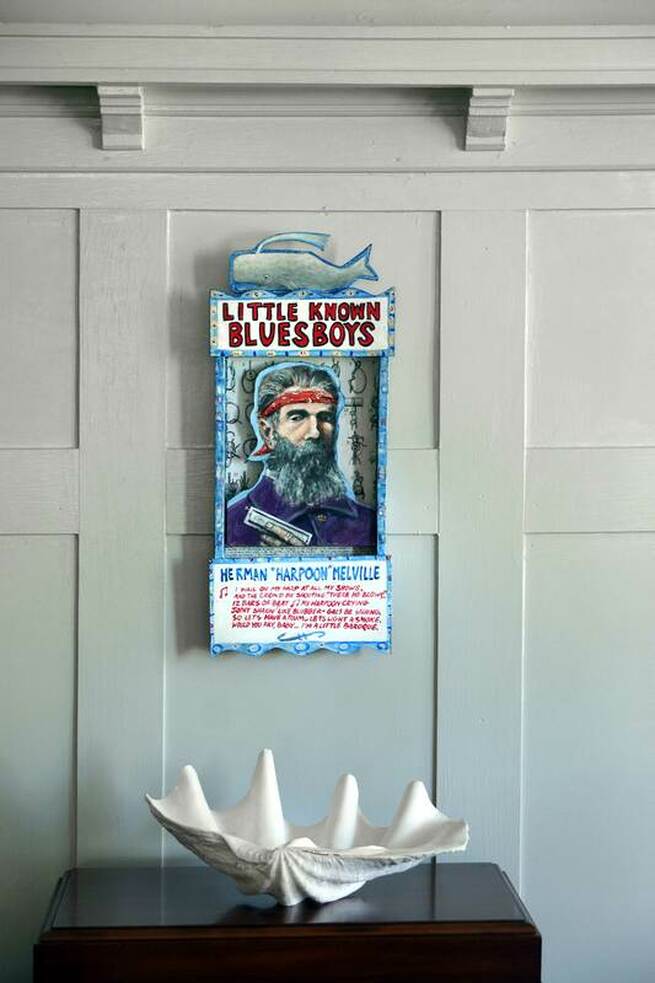

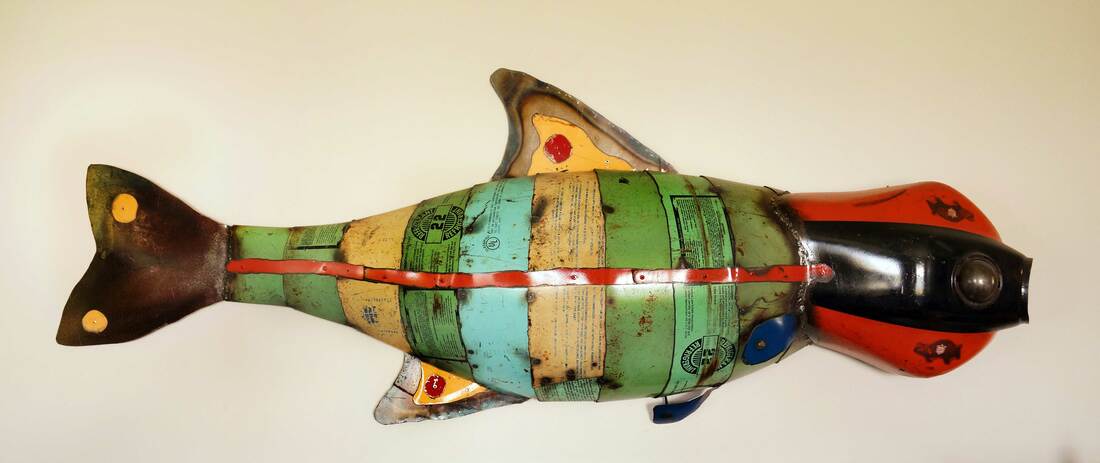

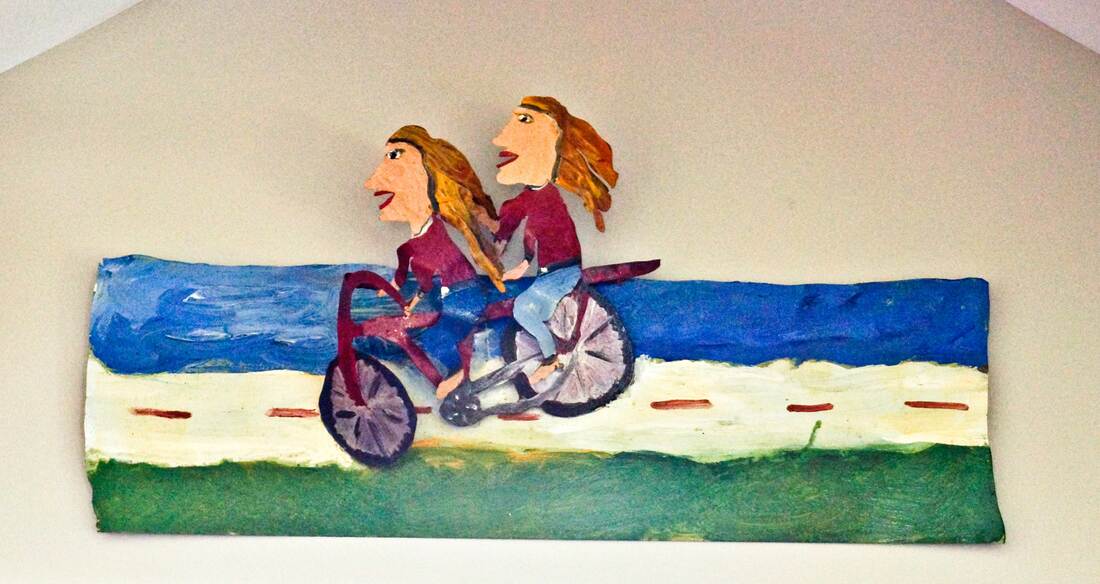

In addition to the dining room make-over, the entire 2300 square foot interior was repainted as well. “You might notice everything is grey,” Kit points out. “It doesn’t compete with the woodwork, which is the jewel of this house. It also makes a wonderful backdrop, letting the artwork come forward. And this house just calls for art.” Kit has answered that call. She began her art collection when she was twenty and hadn’t stopped for the last fifty years. While the collection ranges from traditional Choctaw basketry to contemporary paintings, she says the pieces have one trait in common. “Imagination,” she says. “Creativity. There's freedom of expression, even in the folk art pieces.” Much of her own work is on display as well – glass sculpture, photography, painting and pottery. Even mosaics. The showstopper in the kitchen is a stove backsplash Kit created from shells and dish shards she collected on the beach after Katrina. As a young girl growing up in Jackson, Kit wanted to be an artist from the time she was 13 (“Maybe I just liked making messes,” she jokes). She took art lessons from a “magical” teacher named Elsie Mangum, who introduced her eager student to painting and drawing. Later, while attending Milsaps, Kit worked as an assistant to the renown Mississippi artist, Carl Wolfe. She immersed herself in art, focusing on watercolors, fabric design and pottery. During summers, she studied at Memphis Art Academy. Kit also attended Mississippi University for Women before graduating from Ole Miss as an art educator with minors in history and English. Later in life, starting in the early 200os, she began studying art glass, twice attending The Studio of the fabled Corning Museum of Glass in New York state, where she studied with internationally recognized Donna Milliron. While there, Kit became part of a new “Garage Movement,” which advocated use of techniques and equipment that would allow glass artists to make a working studio in a garage.

While Kit kept her artistic flame alive, her first career-track jobs involved promotion and marketing for state parks. That led her to eventually becoming director of the state craftsmen guild, where she helped raise seven and a half million dollars for a permanent crafts center in the state. Serious illness led her to resign the position. When her health allowed, she returned to the post and oversaw the construction and completion of what’s become a state showpiece in Ridgeland.

She also worked for the state’s Wildlife and Fisheries agency, where she was one of four people to write a program that helped people with developmental challenges to have outdoor experiences. The team was recognized with a prestigious Governor’s Award. She calls that “the most fun job I’ve ever had in my life.” Kit has also served as state director for the Mustard Seed Foundation and later, as president and CEO for the Mississippi Make-A-Wish Foundation. To celebrate her retirement several years ago, she climbed Mount Whitney. The timing was coincidental. Climbers must win a lottery to receive a permit to climb the mountain. Kit had put her name in eight years before. Over a two-week time-period, Kit and a friend hiked two shorter ascents first to acclimate themselves to the mountain’s 14,000+ ft. elevation. She laughs about being a Mississippi flat-lander where “the highest place in the state is Duck Hill, which is 200 feet above sea-level.” Now the main restoration of the Craftsman cottage is complete, Kit’s finally enjoying a more relaxed coast life – spending time with her grandchildren and playing bridge. She’d like to return to her glass work and painting – on canvases this time instead of walls. But she sees the house as a continuing artistic project. “I’m still working on it,” she says. “I’ll always be working on it, I guess. I see it as a creative opportunity.” Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed