The popular event returns with a big day of music May 29 after a three-year hiatus.

- by Lisa Monti

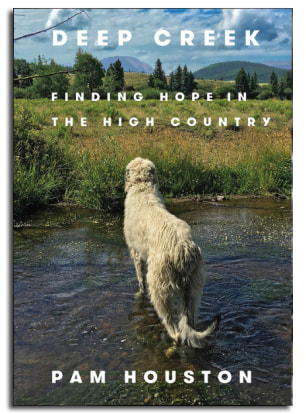

Cradled in the Colorado Rockies with a menagerie of animals, author Pam Houston comes to terms with her past and finds strength in her surroundings.

- story by Scott Naugle

Author Pam Houston will sign books and speak about her new memoir, Deep Creek, at Pass Books, 300 E. Scenic Drive, Pass Christian, on Thursday, Feb. 21, 6pm - 7pm. Click here for more details.

Houston recounts and contextualizes her struggles from a childhood of physical and mental abuse by both parents forward through decades of introspection, eventually locating a measure of peace and happiness in the present day. She sourced both therapy and solace from a large ranch in Northern Colorado, high in the Rocky Mountains, near the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

Many know Houston from the best-selling Cowboys Are My Weakness, her work as a columnist for Outdoor magazine, or the collections of short stories. She is currently the Director of Creative Writing at University of California, Davis and travels the world mentoring at writer’s workshops. Houston unearthed her uphill, rocky footpath to a mountainside respite after years of agonized wandering, “… and so my mother died, drunk and unhappy, and I found my way to this ranch, where I protect and am protected by animals, this place where nature controls how I spend my days and how I spend my life, this place where I can love every season.” The four-legged menagerie loved by Houston includes Icelandic sheep, dogs, mini-donks, horses, cats, and a short visit by an orphaned baby elk. Within all the moments of pure joy the animals inspire, there are also notes of sorrow. “In 2014 I lost Fenton Johnson the wolfhound,” she recounts. Houston was out of town leading a writer’s workshop when she received word of Fenton’s failing health. She returned home immediately by air, landing in a Denver snowstorm. “The weekend was everything all at once. It rained and snowed and blew and eventually howled, and I slept out on the dog porch with Fenton anyway, nose to nose with him for his last three nights.” The story of Fenton was an emotional one for me, striking close to home. I recently lost Snopes, a feisty, gnarling, grumbling, old, five-pound poodle, an ever present companion in charge of the house for the past ten years. When I received the call that Snopes was dying, I stood helplessly in chilly air on a concrete sidewalk corner outside of the office at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. I am consoled by the fact that he died in the arms of the only other person who loved him as much as I did. It was a Sunday mid-morning in Pass Christian several months ago and Pam Houston sat down beside me in a green upholstered armchair. She held her coffee in a white porcelain cup, silently, absorbing, watching the sunlight sparkling and bouncing off the undulating Gulf water. The previous evening, a whisper before midnight, I listened in awe as Pam stood in a parlor just up the street on Scenic Drive, ten or so others sprinkled around the room, reciting a long poem, one that she explained had moved her. I’ve forgotten the poem, but the passionate recitation mesmerized me. I was taken by someone so soulfully enthralled with emotion and ideas as conveyed through poetry. Now, she leaned toward me in the light-washed room and asked what I thought of Hunger. “It is one of my favorite novels,” I blurted. “Several years ago I read through all of Knut Hamsun’s work.” My response, judging by the expression on her face, initially appeared to puzzle her and then slowly changed to one of slightly bemused understanding. What kind of a person responds with an obscure Norwegian novelist’s work, a Nazi-sympathizer from the last century, when at that moment Roxane Gays’ Hunger: A Memoir of Body was at the top of the bestseller list? Houston gently corrected me. “In spite of the encroaching darkness, there’s nothing out here to be afraid of,” Houston recalls in Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country before a late day walk on her property. “Coyotes are not brave enough to attack a full grown woman and a 150-pound dog, even a whole pack of them. Mountain lions hunt at dusk and dawn, but in this country, there’s never been an attack on a human. A black bear won’t be hanging around on the riverbank, but even if he were, he’d hear us before we’d hear him and hightail it back into the forest.” There’s not much of anything, two-legged or four-legged, that Houston is afraid of any longer. Houston’s depth of insight and barebones honesty, her fluency and descriptive agility with the written word, brings Virginia Woolf to mind, ruminating in A Room of One’s Own: “The whole of the mind must lie wide open if we are to get the sense that the writer is communicating [her] experience with perfect fullness. The writer, once this experience is over, must lie back and let [her] mind celebrate its nuptials in darkness.”

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country is a memoir of strength, resilience, and love. It’s an affirmation of life, a “nuptial” unifying beauty with honesty, a Rocky Mountain transcript of Woolf’s ideal. I hope that Pam Houston permits herself a moment of celebration.

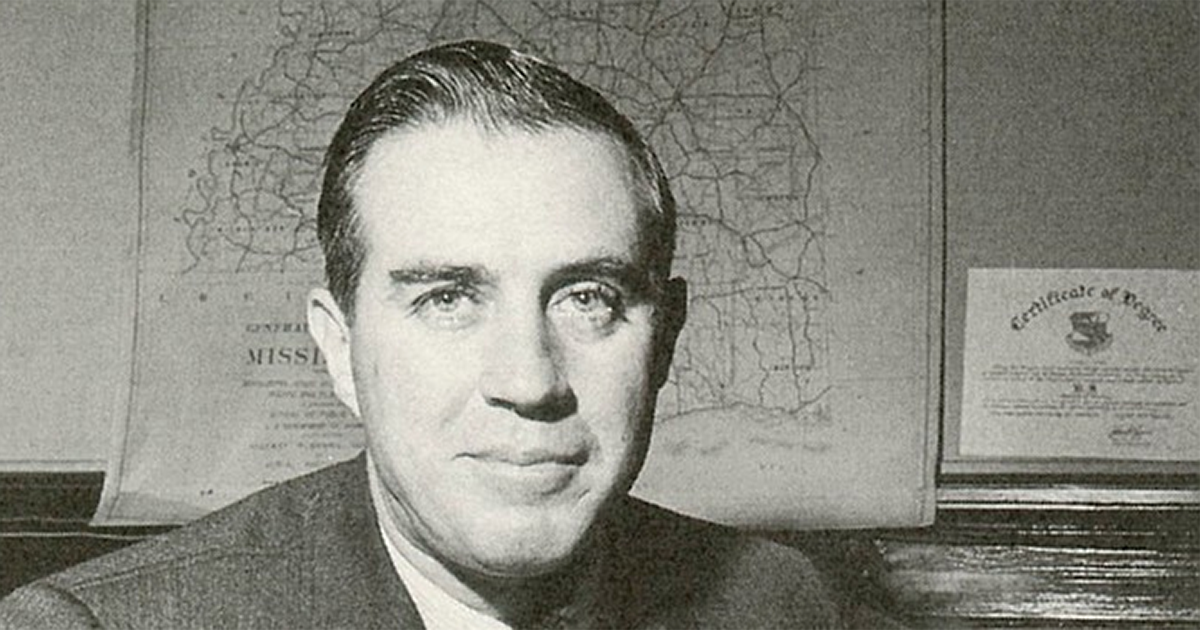

Rheta Grimsley Johnson believes she was privileged to know a few of the old-school, legendary reporters from 'way back when print ruled journalism. One of them was Mississippi's Bill Minor.

Editor's Note: There's a free showing at the documentary about Bill Minor Rheta refers to in this story on Thursday, April 12, 2018, at the Gulfport Westside Community Center, 4006 8th Street, Gulfport. There's a reception at 5pm and the screening starts at 6pm. It's sponsored by the Historical Society of Gulfport.

In George Wallace’s Montgomery, I grew up on Ray Jenkins’ liberal editorials, the “Ask Andy” science feature and the comics. Especially the comics. I must admit that Brenda Starr might have had more to do with my career choice than Huntley, Brinkley and Ray Jenkins combined.

Not to disparage today’s working press – enough unfounded criticism twiddled and Tweeted lately – but I miss the staccato rhythm of the old-fashioned newsroom and the disposition of old school reporters. They never expected to be liked, for one thing, which is probably why they sometimes were idolized. Two things happened recently to satisfy my nostalgic longings for solid, shoe leather journalism out of the Damon Runyon mists. One was the movie “The Post,” which celebrated the guts it took for The Washington Post to publish the Pentagon Papers. I went to the movie not expecting to like Tom Hanks as Ben Bradlee, though I like Tom Hanks. I simply didn’t think he could reach the gravitas bar that Jason Robards set so high in “All the President’s Men.” But Hanks did. He exhibited the sardonic wit and passion for truth that characterizes the best in the trade. If your mother says she loves you, check it out. The second surprise was local, a documentary screening in the Pass Christian library of “Bill Minor, Eyes on Mississippi; The most essential reporter the nation has never heard of.” The room was full. In the film the late, great reporter Bill Minor pretty much narrates his own story, drawn out by the questions of Ellen Ann Fentress, producer and director. Ellen Ann was hired by Bill when for several years he ran a liberal alternative weekly in Jackson, The Capitol Reporter. In all, Louisiana native Bill Minor wrote from Mississippi for 70 years, beginning with Theodore Bilbo’s funeral in 1947. His long career of civil rights reporting began then, writing for The Times Picayune until that New Orleans paper closed its Mississippi bureau. In his last decades, he wrote syndicated columns that did what they could to keep the state’s politicians accountable and honest. Throughout his long reporting career, Bill Minor made enemies, the right enemies, and was threatened and sued and maligned. Our paths crossed in the early 1980s in the Capitol Newsroom in Jackson. Minor was introduced to me as the dean of Mississippi journalists, a title he earned. He also was a really nice guy. As a reporter for Jackson’s struggling United Press International, I quickly learned that Bill was the man to see if you had a question about anything to do with the state’s byzantine politics. He had the key to the vault of institutional knowledge. And he didn’t mind sharing. I last saw Bill in Athens, Ga., at an annual gathering of old civil rights reporters given an ironic lofty title, the Popham Fellowship. It was named for John Popham, a celebrated New York Times reporter who traveled the South to the tune of 50,000 miles a year. His race reporting was the gold standard. I was there to write a column in 1999, the year Popham died. The decision had to be made whether to continue the yearly gathering. It was an emotional, inspirational scene. I’ll never forget the arrival of one of my professional heroes, Bill Emerson, formerly of Newsweek, holding his portable oxygen apparatus in one hand, his whiskey bottle in the other. I can’t remember how the vote went about future meetings, but I will remember till I die roaming the halls of the unremarkable chain hotel amongst the giants of our print trade, including Bill Minor, Claude Sitton, Joe Cumming and the aforementioned Ray Jenkins. The war stories were from the front line. The wit and stamina was legendary. An era was winding down, but not quietly. When Chet Huntley retired from The Huntley-Brinkley Report in 1970, the network gave him a horse because he was moving home to Montana. Huntley lived only four years after retiring. Bill Minor died last year at age 94, still reporting and writing until almost the end, when he became too ill. His last columns were among his best; there was a lot that needed saying. He never left Mississippi or abandoned his hope that race relations and hearts here could change. I am not alone in missing him.

Find out more about Rheta's books at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

Award-winning author Rheta Grimsley Johnson unpacks her holiday decorations and some thoughts about what's supposed to be "the happy time of year." Big Bonus: the recipe to Lera Johnson's Oatmeal Cookies.

Find out more about Rheta's books at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

Maybe we weren’t “laid off down at the factory,” as Merle wrote about, but not all years are created equal. Some simply suck.

That’s when it’s time to put one Size Nine in front of the other and carry on. If you think you’ve sensed a mood here, you have. I don’t mean to hate December/It’s meant to be the happy time of year… Sometimes by simply going through the motions you get caught up and carried along. So I trudged through the carpet of leaves to the storage room behind the car shed. In it are the Christmas boxes shoved haphazardly into hibernation in past years. Starting the intimidating task of unloading decorations didn’t make me merry, but it did make me thankful. I put “Blood Oranges” in my boom box and began. There is the music box my sister made in ceramics class back when there was such a thing as ceramics class – back before double-knit. Mr and Mrs. Claus dance before a mantel with stockings to the tinny music of “I Saw Mama Kissing Santa Claus.” On the ceramic calendar hanging by the ceramic fireplace the date is December 24, which is exactly when the handmade gift arrived in Jackson, Mississippi, the year I Iived in a South Jackson rental we called The Smurf House. My former husband and I shared the big house with several single men, and the Smurf theme seemed obvious and stuck. The two vintage plastic snowmen come tumbling from another box, top hats at jaunty angle. I remember the first Christmas Terry Martin spent across the road from me in his little red house. He gave me those retro Frosties. The warm feeling having him so close gave me was the real gift. How many people can say their closest neighbor is not just a geographical accident but someone in philosophical and political agreement about almost every fundamental thing? Not many. We are blue dots in an ocean of red. The red sled my niece Chelsey made from Popsicle sticks remains intact, despite my careless packing. So does the Plaster of Paris snowman with stick arms. A friend’s child sold me that treasure from his private fund-raiser. Children are not only clever but enterprising. By my sofa are a dozen or more of those home and garden magazines that make you want to burn down your own house and start over. I wonder where the people with thematic, color-coordinated trees and rooms stash their stick sleds and Plaster of Paris snowmen. Worse yet, how do healthy people justify not decorating at all? Next from the bubble wrap rubble comes the chalk Santa my father won for me at a Florida county fair. I was six. He was deft at pitching nickels. The games back then evidently weren’t rigged. And if the Santa is coming out, so must the snow globe my mother mailed at great expense when she heard my modest collection had frozen and burst. The event cured me of collecting, but Mother insisted I should have one globe at least. I find the straw animals my friend Edwin “Whiskey” Gray has given me over a dozen years. They are the ornaments that remind me of France, not unlike the ones sold at the flower market that surprises you when you emerge from the Metro. Chelsey once told me that anything I really love reminds me of France, and I guess that is true. Speaking of. I search for and find the three French hens painted on a red egg replete with the Eiffel Tower. Unpacking accomplished, I’ll next bake the late Lera Johnson’s oatmeal cookies, a recipe that makes enough to share with her two grown sons. Back when folks cooked with Crisco and I was young, hungry and skinny – not to mention terrified of what the future held -- there was one thing you could count on. Whenever I stuck my hand into my mother-in-law’s cream-colored cookie jar, I never once hit bottom. Lera Johnson’s Oatmeal Cookies 3 cups Quick Oats 1 cup brown sugar 1 cup white sugar 1 cup Crisco 1 cup nuts 2 eggs 1 and a half cups flour Cream sugar and Crisco; mix in eggs, oats, flour and pecans. Bake at 300 degrees until brown.

Across the Bridge - Oct/Nov 2017

Award-winning author Rheta Grimsley Johnson on how art has the power to transport and transform us - especially the work of Mississippi coast artist John McKellar.

Find out more about Rheta's books and read her latest syndicated columns at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's new gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

The man can write – I mean McKellar as well as Melville. You might say John is the Sybil of coast artists, with multiple personalities, defying categorization and having fun. I went to a recent “pop up” exhibition – I question that term; nothing as good as this “pops up” like a ring of mushrooms -- at the Ohr O'Keefe Museum of Art’s Creel House in Biloxi. Along with John and Kerr Grabowski of the Bay was Mary Hardy of Ocean Springs. The talent was thick enough to spread on French bread. The small cottage was so full of admiring art patrons that I had to spend a lot of time outside near the taco truck. It was exactly the kind of enthusiastic turnout that gives the coast its well-deserved reputation for artistic appreciation.

I think coast artists are a bit spoiled by such gung-ho receptions. Nobody sits alone in a gallery waiting to be noticed south of I-10. Up here, bumping on Tennessee, it’s often a different story.

I’ve spent the past year trying to start a shoestring gallery in Iuka, population 3,000. I’m making it up as I go along, and learning a lot about art and humanity. From my perspective, it would seem there are far more good but starving artists than patrons, at least in my particular neck of the woods. Almost every day, some eager artist without a place to show his or her work arrives with an excellent portfolio, often stored on a telephone. I don’t have the room or budget to accommodate all the deserving painters and photographers and potters who drop by. It is a shame, really, how much talent stays stacked up in remote studios instead of hanging on museum or gallery walls.

Just today I went with a friend to the library and had to turn on the exhibit room’s light to see some wonderful watercolors by a local artist. We were the only visitors.

I’ve puzzled much over the difference between communities that don’t just embrace but bear-hug the arts, compared to those towns that think a painting is a frill meant for rich folk. It is not. When I was a young girl, my mother bought the kind of art she could afford: two prints in cheap wooden frames of Asian street scenes. She didn’t pay money for the art, but swapped the Top Value stamps she collected at the Kwik-Chek grocery store in Pensacola, Fla. Now even at the Top Value redemption center there were more practical choices than art. Lamps, cookware, dishes. Mother, however, seemed hungry for something pretty to look at as she went about her housewifery day after day. She chose art. I can remember sitting on the floor beneath the two prints and making up stories to go along with the rather generic street scenes. In one, a beautiful woman was scurrying along, and I imagined where she might be headed. I never gave out of storylines, which sometimes overlapped with what I’d last seen on “Gunsmoke.” That’s what art does, in a way. It transports us to places we may never visit, inspires us to think about both foreign ports and home in a different light. It makes us yearn to be seaside, or in the mountains, or on top of a worn bedspread next to a yellow dog. It sometimes makes us laugh. John’s Cat Island is the South on my inner-compass, a destination hidden in my heart and head. Someone Who Mattered

Author Rheta Grimsley Johnson remembers a friend who understood the value of many things, especially silence.

All this happened after my second husband, Don, died in 2009. I could not suffer fools, who seemed all of a sudden to be everywhere. It was a regular fools’ convention, gathering outside my door.

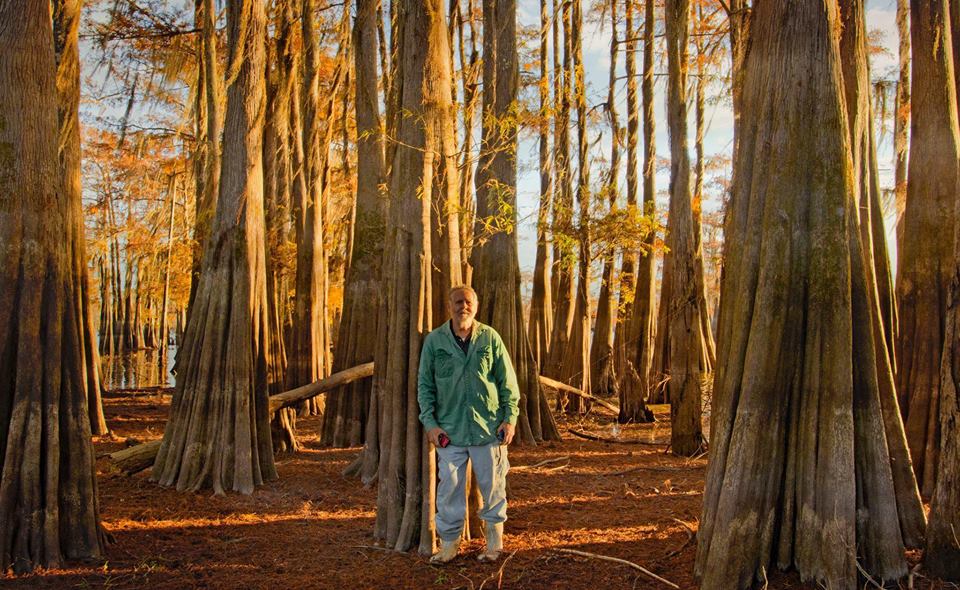

Many wanted to compare their own grief with mine, as if we were in a global grief competition. When my mother died, they’d begin, meaning well and telling best how to cope, irritating beyond belief. Or, someone might recall with misty eyes, when my husband died 30 years ago, I swore never to remarry and have not. Bully. They congregated on my porch and ate and drank and laughed, all in the name of keeping me company. I wanted desperately to be alone. They left me alone when I wanted company. Fools, fools, fools. Everyone had an opinion about honoring the dead. Some lobbied for marble, replete with dates, else The Almighty would not know the deceased was deceased. In-laws and friends wanted some of the ashes to feel more a part of the sorrow. I resisted. I wanted to scatter most of Don’s ashes by myself in the Atchafalaya Swamp. I thought it fitting. His happiest hours were in that swamp. By himself. Problem was, I had a plan but no boat. But I knew someone who did. I drove all day from North Mississippi to Henderson, La., straight to the home of a friend who did not irritate me. Not then, not ever. Greg Guirard was standing in his yard as if we’d had an appointment. I told him my mission. “I’ll take you to a pretty place,” he said. That was it.

Because he was a crawfisherman, his yard always was full of boats of every size and description. Motors hung from tree limbs like over-sized fruit. He backed my old red Ford to one of his boats on a trailer, and quickly – we were trying to beat sunset – we drove to the nearest landing.

The pretty place was Bayou Benoit. Greg had a houseboat bobbing there. He disappeared, not literally, but leaving me alone to the most private of tasks. I don’t remember that he said a word. No intrusive or sentimental claptrap worthy of Hallmark. No suggestions about moments of silence. No toasts. Certainly no prayers. Greg got us back to the landing and my truck before dark. When Greg died last month, I mourned again. This time I find myself on the irritating side of the grief equation. He was a man who meant so much to so many people that I want to grab strangers by the lapels and tell my Greg stories, to explain his worth again and again. Now I am the noise. What was there about his calm presence that inspired so many? He taught literature, wrote books, took countless swamp photos, fought environmental battles against oil companies with his fellow crawfishermen. He reclaimed sinker logs, made beautiful cypress furniture, planted oak and cypress trees, lived simply, honored his elders, had an amazing sense of humor and was one of the best-read men I’ve ever known. And he helped a widow scatter her husband’s ashes. But none of that exactly explains why he will be remembered when so many of us will not. It is tempting – and irritating – to make a dead Greg into a super hero. “Greg,” I once said to him while tagging along to check crawfish traps. “You are a beacon of contentment.” “I’m a beacon of Lexapro,” he retorted. He was the most guileless of heroes, the most modest of men. For my money, it was mainly this that made Greg Guirard unforgettable: He knew when to stop talking and listen. His deafness made him bend forward as if he wanted to hear everything you might utter. As if yours was the most important voice, not his. And now, I perhaps have sated your curiosity about a giant of a man. I will take a page from Greg and from here on remember him in silence. What Katy Did

Award-winning author Rheta Grimsley Johnson introduces a moving new book by noted journalist John Branston.

“Watch out for snakes!” I warned.

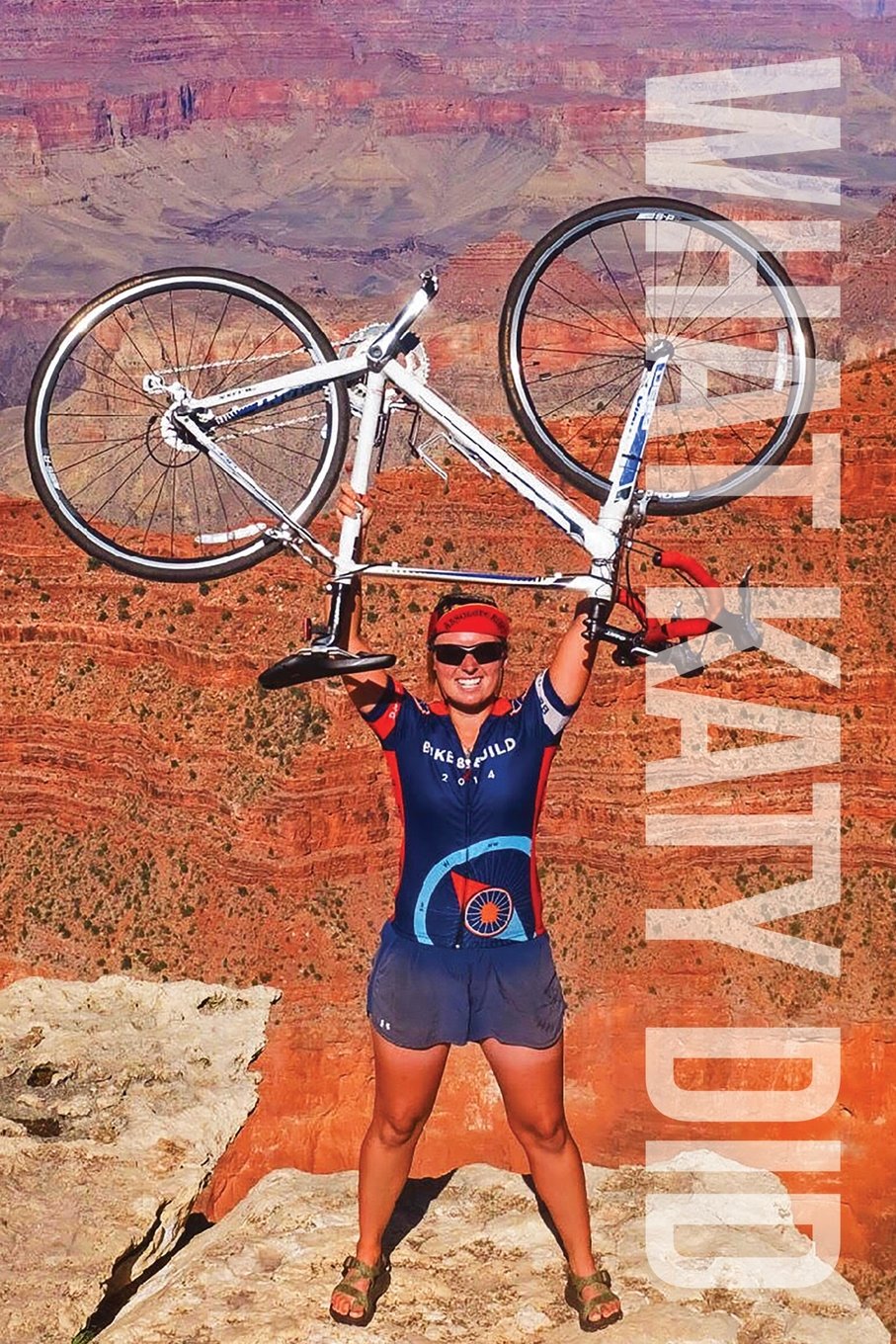

“Kaboom!” yelled the dam-destroyers. They were fearless. That’s where I’ll keep Katy Branston. In the hollow, in the branch, in the box of faded snapshots under the bed. For somewhere there is a photograph I took of her that dam-building day. She is standing with her father, mother and brother, on the side deck where I’d line them all up each annual visit. The Branstons, a handsome couple, had such beautiful children that you felt compelled to document their big eyes and pinch-able cheeks. I once tried to sell my publisher on a photograph of Katy’s brother Jack for a book cover. I am talking cute. In 2014 I received an email from Katy announcing she was leading a bike tour across America to raise money for something called “Bike and Build.” It was a fundraising scheme for affordable housing that involved pedaling nearly 4,000 miles in 75 days. Once again, I marveled at time’s swift passage. Little Katy was grown and gone, already graduated summa cum laude from North Carolina’s Elon College and living near her brother in Montana. For a while that year I was current. Katy blogged about the trip, and I saw a few photographs and read well-written accounts of her adventures. She made it safely with her 32 charges to the Pacific Ocean. Still fearless, I thought. But this past November when Katy’s father, John, called to tell me she had taken her own life, I refused to believe Katy was age 29; it simply could not be. She was the small girl in overalls. Now, because life is so damn tough, there’s a book you should read, as close to the bone as anything ever written. Titled What Katy Did, it also is what John did after his daughter died. He wrote, same as he’s done every day of his adult life. Katy had started writing a book and wanted to share it with friends and family when she turned 30, which should have been this month. John finished it for her.

John and Jenny Branston have been in my life since 1981, when John and I worked in a small bureau for United Press International in Jackson. No, we didn’t deliver packages in a brown truck as many assumed. UPI, not UPS. We were reporters -- young, driven, competitive. He was a Michigan Yankee. I was Deep South. But we were good friends.

We even took jobs with the Memphis newspaper the same day, sharing the ride up from Jackson for our respective interviews. We both eventually left that paper, but print journalism had its hooks in us. The Branstons named their firstborn, Jack, after Jack Burden, the reporter in All the King’s Men. John, an exceptionally fine writer, authored a well-received book, worked for Memphis magazine and, for years, the alternative city paper. I have seen the Branstons more lately than I have in decades. John had retired, was a bit restless, and he and Jenny visited us in the Pass. They fell in love with the place. It happens. Before we knew it, they bought a second home on Second Street previously owned by a lady named Gisela who grew up in Nazi Germany and survived Kristallnacht. The Branstons started giving the house the clever decorating touches that Jenny is famous for in Memphis. John rejoiced in doing some physical work for a change. Then they lost Katy, who never saw the new family home in the Pass. She never saw Cat Island in the distance, or up close, the siren sight that convinced her father to locate here. I knew for certain that John, living through the worst imaginable thing any parent could face, would write something. He would have to. It is how writers work through everything, joyful or bleak. Especially for reporters, it isn’t real until it appears on the page in short declarative sentences. “This is a short book that can be read in an hour or two,” John writes, “which is fine because that’s about all I have in the tank and Katy wouldn’t want us moping around. Katy believed in living true….” It may be short, but it is perhaps the most profoundly heart-breaking story of struggle I’ve ever read. Written by a seasoned journalist, it is full of evocative, but never maudlin, details that make Katy as real to me as she was that day in the branch. She taught herself to play the ukulele. She worked for Habitat for Humanity in Whitefish, Montana. She faced down a mountain lion. She missed her folks. Using his own words, Katy’s words, her friends’ countless tributes, John has managed to lasso his sorrow into what may be the single best profile I’ve ever read. “It is possible to have a life after horror and loss,” John concludes. “Gisela lived 77 years after escaping the Nazis. Walter Anderson was most productive after escaping from the state mental hospital. Pass Christian completely rebuilt itself after deadly hurricanes in 1969 and 2005. I have hopes.” He is following his daughter’s example. Living true. Chopsticks on an Old Upright

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson reflects on the pleasures of being impractical.

Find out more about Rheta's books and read her latest syndicated columns at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's new gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

My Girl Scout leader, not so much. I figured I got enough Bible stories in Sunday School and didn’t have the patience for a felt Zacchaeus up a felt sycamore tree.

I’ll have to admit, however, that the bad judgment tag stuck. I’ve been told by my father and two husbands that I make impractical decisions, first cousin to bad. I choose to think of myself as romantic. I made another such decision just the other day. Impractical, not bad. At least I hope. I bought a piano. I have no place to put it and couldn’t play it if it did play. Which it does not. Did I mention this was a tad impractical? For years I’ve wanted an old upright piano. My grandmother had one, could make even the most puritanical, blood-soaked hymn sound like a honky-tonk hit. The figurines she kept on top of the piano danced when she played, and the fat on her upper arms shook to the beat. After my grandmother died, my aunt sold that iconic upright to a stranger for $50. Better that than let family benefit. Soon enough I rented a furnished house in Monroeville, Ala., Harper Lee’s hometown. We were caretakers, actually, my former husband and I, settling in amongst the dry-rotting treasures in a rambling mansion in the woods. The cost we paid for baby-sitting such splendor was $200 a month. The house had an old upright piano. We didn’t have the money to get it tuned properly, but every party centered around the instrument. We were young. There were many parties. Always there was someone who could coax a tune from the yellowed ivories. I played at the level of “Chopsticks” and “Heart and Soul,” and my grandmother’s favorite stride piano song, “Redwing.” But planted in me during that brief period was the desire to sit down at a keyboard and become a Scott Joplin, or, better yet, Jerry Lee, a man who could take “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from audio doggerel to Grade-A groove. So when a friend took me to see an old house she’s buying in the Pass, I couldn’t help but notice the old piano sitting idle in the modified dogtrot. Next thing I knew, I was talking to its owner about what would happen to the treasure. “It can be yours,” he said. “For $1 and getting it out of here.” “You were over-charged,” my former husband said when I told him what I’d done. “They usually pay you to get it out of there.” I reminded him of the fun we’d had with the Monroeville upright, but evidently in his maturity he’s forgotten the delight he felt when I taught him the treble part of “Silver Bells.” I already had realized the impracticality of my purchase after calling Three Men and A Truck – more like 30 men with 15 trucks -- who all put the bottom line for moving a piano at about $400-plus. Turns out, it takes four men to move one safely, and this particular antique was extra heavy. I knew the piano needed work. Both the furniture and the innards were pretty crusty. So I decided to have the movers shove it into the garage, the only place I could think of big enough to accommodate a piano. “So you’ll need another $400 to move it out of the garage when you decide where you want it,” my current husband said. Husbands are always demanding you use the soft pedal. I decided to shoehorn my acquisition into the living room, which necessitated rearranging every piece of furniture in the small house. But it fit. A practical woman might be sorry about all of this by now. I’m not – practical or sorry. I still think once a piano expert is called in and works on the guts, and a furniture doctor spruces up the outside, and I learn to play something other than “Chopsticks” and “Heart and Soul” and the two recital pieces I remember, I’ll have the last laugh. Or I’ll sell the piano to another romantic soul for $1. Not a Sign of the Times

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson muses about authenticity, character and signage on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

But I guess that’s how towns stay pretty, fussing over the details. Only sometimes they miss the forest while pruning the bottle trees.

For me, in this age of insubstantial people and things, I find the Pass’ HOTEL sign refreshing, nostalgic. It harkens to the days when college football bowl games did not have long corporate sponsor names and pharmacies innocently blinked DRUGS. I once lived in a humble and ugly apartment complex just offthe interstate in Jackson. It was called Pine Hills Apartments. There were no pines, or hills, just cheap boxy apartments thrown up on a concrete pad. But I suppose few would have rented them if the owners had called it Ugly Sprawl Near Interstate Village. So I guess that’s also why I like the Hotel Whiskey’s approach. HOTEL. No brag, just fact. Written in red like Jesus’ words in the Bible. Easy to see. Not like a fast food joint in the rich part of town that has to disguise itself to be there.

Now when you get to the fine print, the HOTEL’s Whiskey part makes the place sound like a Willie Nelson song. I also like that. All a traveler’s needs encapsulated in the name and under one roof.

“Park your nags, boys, we’re staying at this here Hotel Whiskey.” Seaside towns have all gotten too prissy and pink for my tastes. Even the workaday Apalachicola in the Florida Panhandle has gone boutique. What happened to boats in every yard, and dives? One can only buy so many souvenir golf visors. Beer, on the other hand…. I’m much more put off by pretty little wooden signs swinging from a post and decorated with a pelican than I am HOTEL in red. Something perverse in me, I guess. The Pensacola of my youth may have influenced my taste in towns by the coast. I remember cinderblock homes near the bay, including my family’s, which was painted pink and convinced me we were rich. I can hear right now the cheap glass wind chimes hanging from my friend Margaret’s carport; they made a better sound than any of the expensive ones do now. There were eclectic neighborhoods that mixed demographics the way a blender mixes margaritas, with boats on trailers, or sometimes blocks, as de rigueur as the shell driveways. I’ve always described the Mississippi Gulf Coast as the last remaining authentic seaside place left in the South. When I drive along Railroad Avenue I get the feeling I’m back in the 1950s, with snow ball stands and bars with funny names and tire stores and beauty shops. It’s as if the Panhandle of old and New Orleans had a love child and we’re living in it. After Katrina there’s been the temptation to zone the seaside spontaneity out of communities. It’s good that condominiums were pretty much kept at bay, and historic properties intact, and I definitely believe in separating commercial and residential. But a little leeway for color and character comes with the territory, don’t you think? Take my opinion with a grain of sea salt. Remember I’m the girl that starts her diet with a steak and a sweet, washed down with good wine. Back To Nature With a New Generation

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson discovers a magical trail in the Pass.

Find out more about Rheta's books and read her latest syndicated columns at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's new gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

A Window of My Own

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson embarks on a new career as the owner of "Faraway Places," in Iuka, Mississippi.

Find out more about Rheta's books and read her latest syndicated columns at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's new gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

A Color Line in Far-off France

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson writes from Across the Big Pond this month in the technicolor world of France.

- story and photos by Rheta Grimsley Johnson From Civil War to Civil Rights

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson reflects on her childhood in Alabama and a trail that sheds light on the state's history.

The Chart and the Heart

A trip to the Sunflower River Blues Fest and the new Grammy museum in the Delta, drive home the point that "the heart is where it's at."

- story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson A Blur of Seasons and Satchels and Peach Cream

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson explores the acceleration of passing time, marked by speeding seasons.

Sprinkler Parties and Plastic HeadbandsThe sight of a sprinkler at work in the heat of a summer's day excites the inner kid of this award-winning columnist and author.

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson A.J. Liebling is a Friend of Mine

Award-winning columnist, playwright and author Rheta Grimsley Johnson finds migration is the most effective form of dieting when one lives on the coast of Mississippi.

Sweet Work If You Can Get It

Award-winning columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson takes readers along to Pie Day, an increasingly rare Louisiana Lenten custom, an event that seems tailor-made for adoption by the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Importing Bits of Paradise

A trip to Key West fills Rheta's notebook with some interesting observations - by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed