"Money before coin, jewelry before gems, art before canvas": This delightful new book by environmental writer Cynthia Barnett explores the fascinating world of seashells.

-by John S. Sledge

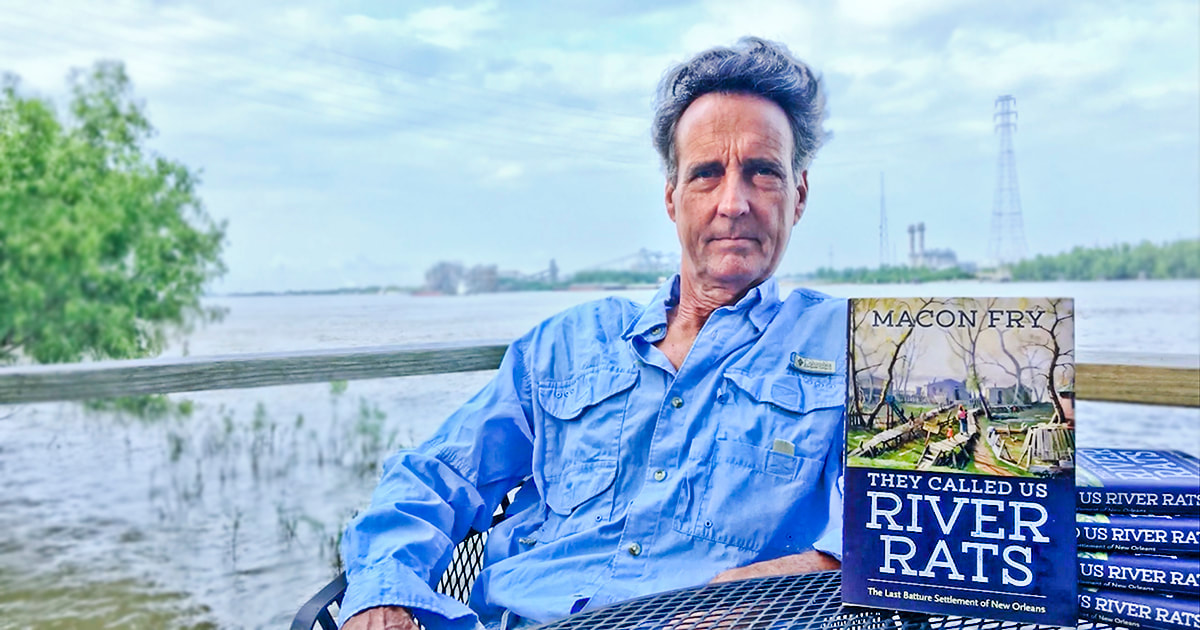

A fascinating new book by long-time resident Macon Fry explores life along the last batture community in New Orleans.

- by John Sledge - photos courtesy Macon Fry, Betsy Shepherd and University Press of Mississippi

Three coast artists are among those being honored at the upcoming MIAL Awards Weekend being held in Pass Christian.

- by Scott Naugle

Shown above are the 2020 recipients of awards: Top Row (L to R): Minrose Gwin, Fiction; Margaret McMullan, Nonfiction; Bark (Tim and Susan Lee), Music Composition (Contemporary); C. T. Salazar, Poetry; Steve Rouse, Music Composition (Classical); Second Row (L to R): Ann J. Abadie, Noel Polk Lifetime Achievement; Will Jacks, Photography; Lemuria Bookstore, Citation of Merit; Stacey Johnson, Visual Arts; Angie Thomas, Youth Literature. Margaret McMullan and Stacey Johnson are both coast residents.

Food, culture and memories are woven together into this extraordinary cookbook, revealing the heart of chef Melissa Martin.

- Story by Scott Naugle

Like any other beloved collection, a collection of books should be displayed and admired, and room design should celebrate it.

- Story by Scott Naugle

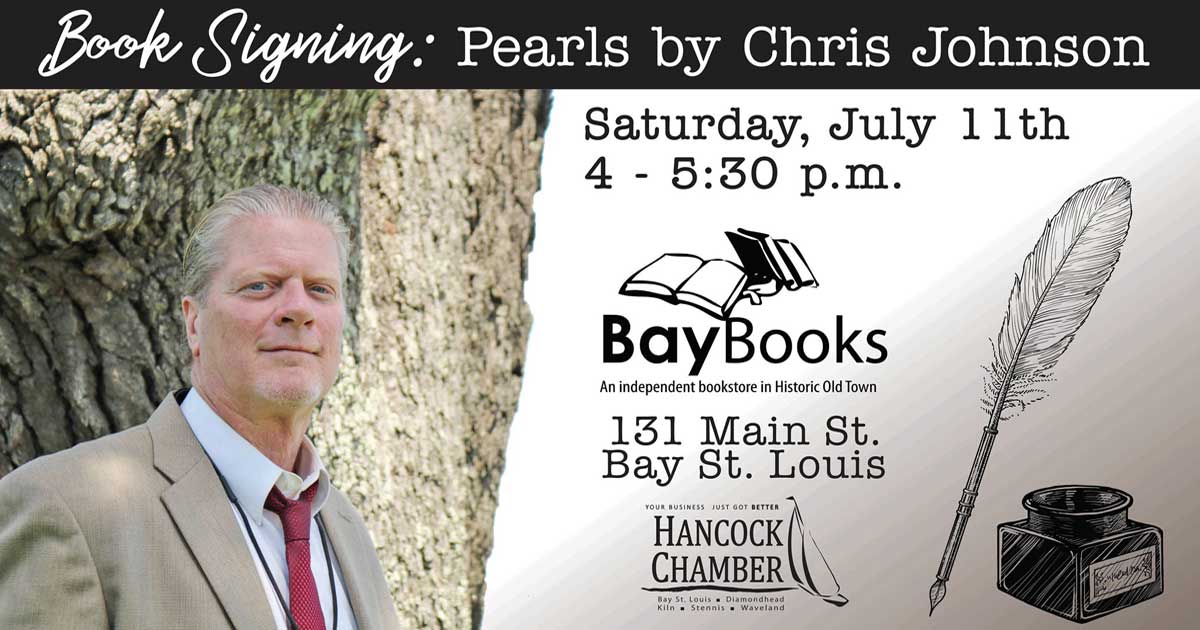

Local attorney Chris Johnson takes the reader on a suspenseful journey in his latest novel, set in Bay St. Louis.

- Story by Anne Pitre

Like the wind, passion can be soothing and persuasive - or relentless and destructive.

- Story by James Inabinet

Some people recall what they were doing when milestone events took place. This author can recall his surroundings when reading memorable books.

- Story by Scott Naugle

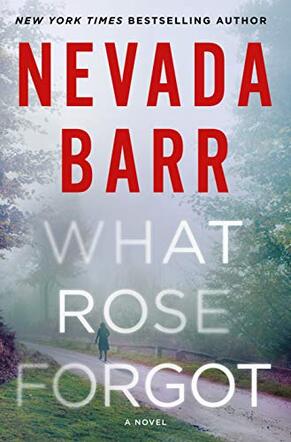

Fasten your seat belts: this new mystery by best-selling author Nevada Barr proves to be a thrilling page-turner.

- by Scott Naugle

Nevada Barr was born in Yerington, Nevada and attended college at the University of California, Irvine. Her degree was in drama and she pursued a career in performance post-graduation.

After a career change, Barr became a park ranger, first assigned to the Natchez Trace Parkway in Mississippi. She created her best-selling Anna Pigeon mystery series based on her experiences working in a national park. In addition to the Anna Pigeon series of novels, Barr also published the novel Bittersweet, set in the early days of the Western frontier and the nonfiction Seeking Enlightenment… Hat by Hat: A Skeptic’s Guide to Religion.

Rose is heavily drugged, and after a bout of pneumonia when the drugs temporarily wear off, she questions why she has been placed in the facility. She foils the effort to begin the drug therapy again and escapes the facility.

Why and how she was committed to Longwood is at the heart of the What Rose Forgot.

Barr’s training in performance and movement is evident in the novel. Rose barely slithers through a partially opened window to escape a man bent on killing her, “Flattening her body against the slope of the roof, she inches away from the porch. The asphalt shingles sandpaper the skin on her cheek and palms. Her feet scuffle in the uncleaned gutter.”

Every small movement and resultant sensation are detailed much like a practiced performer perfects her stage-craft, aware of how movement matters to the audience. And how refreshing it is to have a mature heroine, in other words, a vibrant, intelligent, active character, Rose Dennis, pushing seventy years of age. After escaping from Longwood the first time, “Night air, warm and soft, sinks into her, a balm for a sore body and a troubled mind… Fresh real air is sustenance for the spirit, filled with life-affirming qualities scientists will never discovering windowless laboratories.” Rose is a sexagenarian excited and optimistic to be alive. Grabbing the knife from an attacker, Rose severs his finger. She crawls through shrubbery and undergrowth to hide in a child’s playhouse overnight. Rose re-enters Longwood in costume and subdues a night nurse twice her size. And she cogently and logically thinks through the chain of events and the whiff of a few clues, to figure out who and why this was done to her. Age did not diminish Rose Dennis. Barr creates an extremely believable older female hero who becomes the heart and soul of What Rose Forgot. I read What Rose Forgot in one sitting. I had to. Nothing else mattered to me until Rose Dennis thwarted the bad guys and solved the mystery.

In "The Accidentals," author Minrose Gwin has crafted a classic and moving novel - and it's set here on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

- by Scott Naugle

Meet Minrose Gwin on Sunday, August 18, 2019, at Pass Books (300 East Scenic Drive), in Pass Christian. She'll be reading and signing "Accidentals" from 5pm - 6pm.

Gwin’s nonfiction work includes "Wishing for Snow," a memoir, and "Remembering Medgar Evers: Writing the Long Civil Rights Movement."

Most recently, she was a professor at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "The Accidentals" begins in 1957. Olivia McAlister is an anxious mother of two daughters, June and Grace, married to the dependable Holly, a bookkeeper for the local paper mill company. Holly drives a Nash Rambler and is meticulous in trimming the hedges of their neat, comfortable house. Impacted by and wistful for the energy and vibe of her youth in New Orleans, Olivia cannot find her footing among the routines and housewives of a rural Mississippi community. She’s standoffish, a loner, pining for the intellectual and artistic stimulation of a larger city and the invigorating broader cause she served while working at the Higgins boat factory during World War II. Through bird-watching and opera, Olivia attempts to find purpose and connection. She is an accidental, “a bird found outside its normal geographic range, migration route, or season: vagrant,” explains the "Merriam-Webster Dictionary." With a richly developed interior life, artistic, self-aware, walking through days under a deep and exhausting disquietude, Olivia McAlister joins Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and Evan Connell’s Mrs. Bridge. Intelligent, internally reflective, and articulate female characters in literature are a rarity, particularly through which an author sets the tone of a novel or barometer through which other characters or society are judged. In the opening paragraphs of "Mrs. Dalloway," “… feeling as she did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen; looking at the flowers…” And from the opening of "Mrs. Bridge," “…Now and then while growing up the idea came to her that she could get along very nicely without a husband.” Both are strong independent women challenging the status quo and searching for intellectual fulfillment outside a society dominated by men and commerce. We are introduced to Olivia McAlister in the opening paragraphs of "The Accidentals" as she projects her concerns and desires, “Listen hard now and you can tell what they are saying. This morning the cardinal. Sweetheart, sweetheart, sweetheart, sweet. Then, two houses down, a mockingbird. Redemption, redemption, redemption…Cheer, cheer, cheer. I’m all ears little wren.” Birds represent flight - an escape - while chirping coded messages to the restless Olivia McAlister, plotting her next action that will, through a series of mishaps, lead an escape flight that will be aborted. After Olivia’s death, her daughters and Holly are boomeranged through a series of emotions and actions that further reverberate into the lives of others with tragic consequences – abortions, wrongful incarceration, cancer, mental illness, physical deformity. I must admit that the plot twists in "The Accidentals" were so unexpected, and shocking, that I stopped short in my reading and gasped more than once. Gwin can plot a story like few other writers. She exposes the randomness and elegiac incongruity of Southern life at the twilight of the twentieth century. Like an unrestrained and irrepressible Faulkner spinning through generations of malevolence and wickedness in "Absalom, Absalom!", Gwin’s characters cannot escape their past, the poor judgments of their relations, and pure bad luck. Unlike her fellow Mississippian William Faulkner, Gwin writes with a balance and steadiness, spinning a completely believable story, more grounded in day-to-day life than we may care to acknowledge. “What I know is that there are always stories behind the stories people tell,” muses June, “They are stacked like crackers in a box behind the ones they do tell.” There’s hope and love in "The Accidentals" among and within the missteps, and this, I believe, is one of the reasons I believe it succeeds as an enduring work of fiction. Gwin does not attempt to unearth plausible causes, scrapping through circumstances or family attics for reasons to present the reader as to why something happened. Rather, she understands that art, particularly literature, is where one word or one inferring principle is enough. Gwin gives us a story to contemplate, softly imprisoning the reader in her beautiful and subtle language, as we read late into the early morning hours. Good gosh, Minrose Gwin. "The Accidentals" – a tour de force on so many levels.

"The Accidentals"

By Minrose Gwin HarperCollins ISBN: 9780062471758 Trade Paperback $16.99

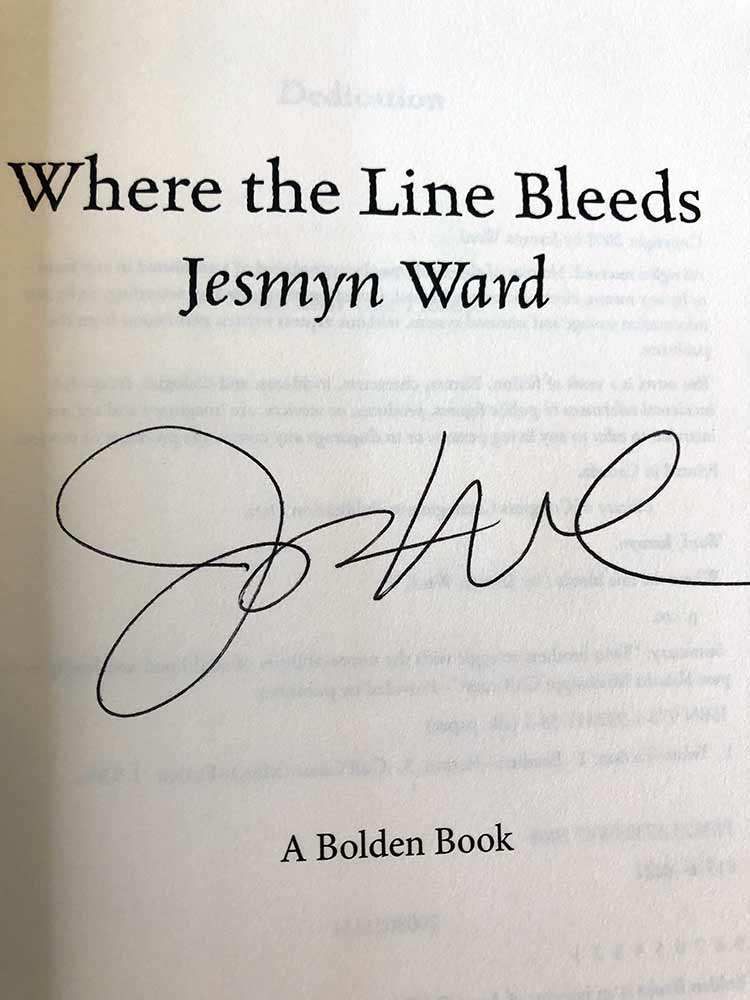

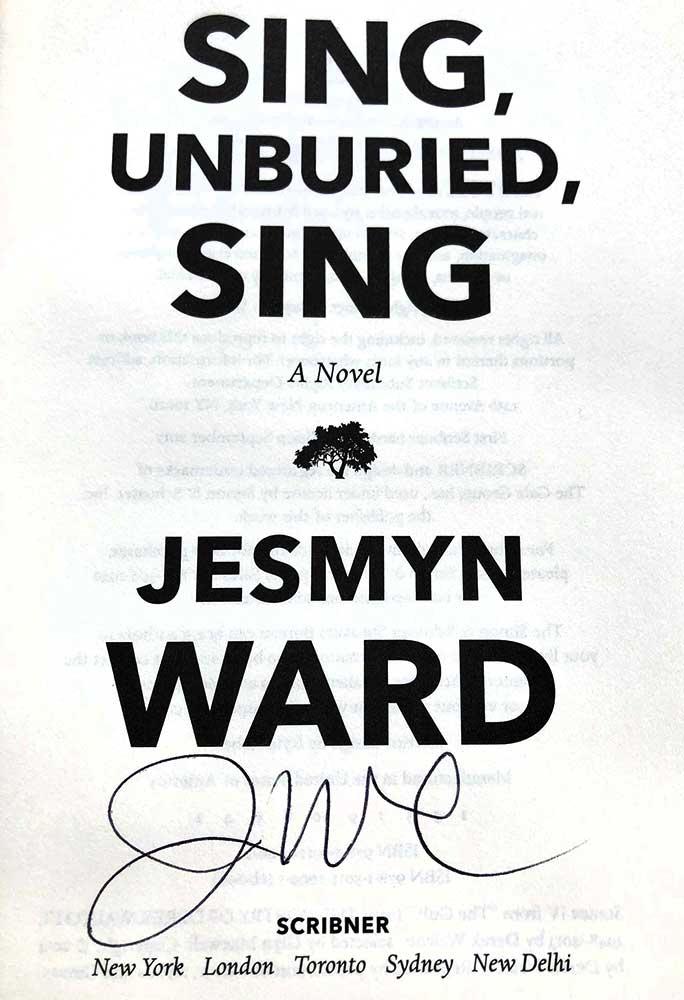

Over a lifetime, an author's signature may change, or evolve. But a book signing is still an intimate experience between the writer and an appreciative reader.

- Story and photos by Scott Naugle (unless noted)

For many, an author’s signature on a book is both a momentarily intimate personalization as well as an opportunity to briefly connect with a favorite writer. A signature signifies that for at least a moment the writer held your copy in his or her hands, underscoring and reaffirming, perhaps, the connection and impact that the work itself left with the reader.

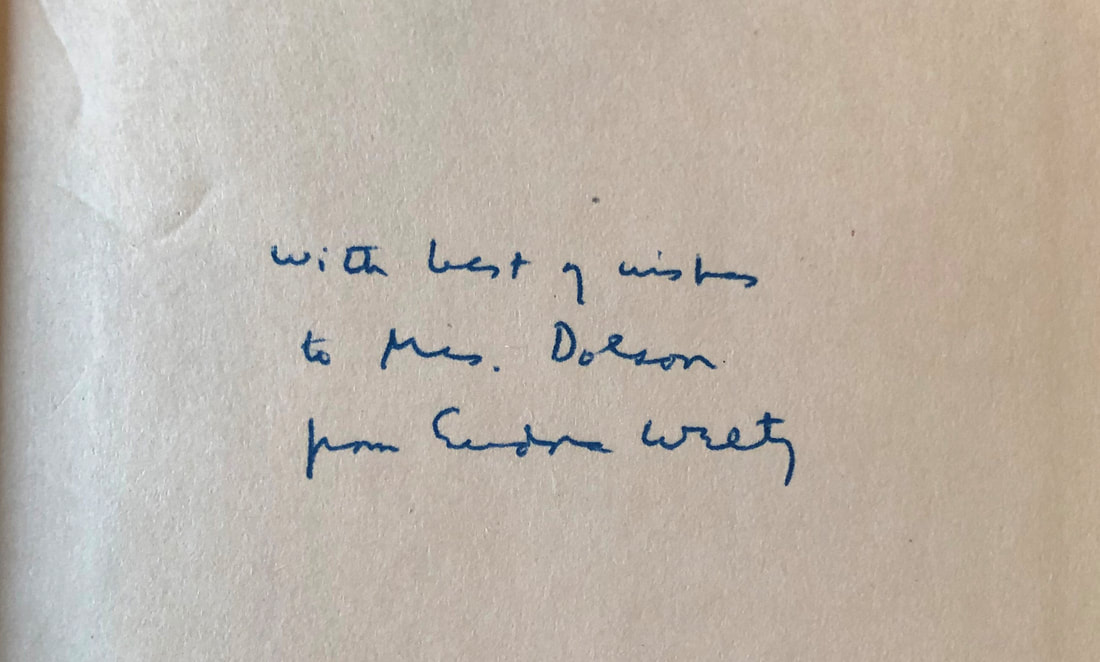

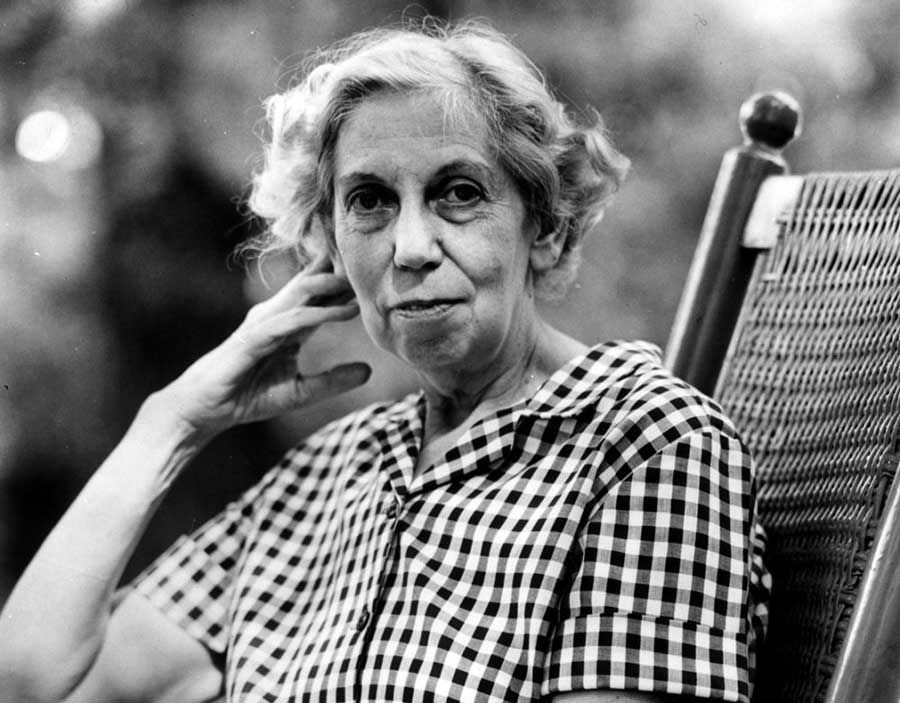

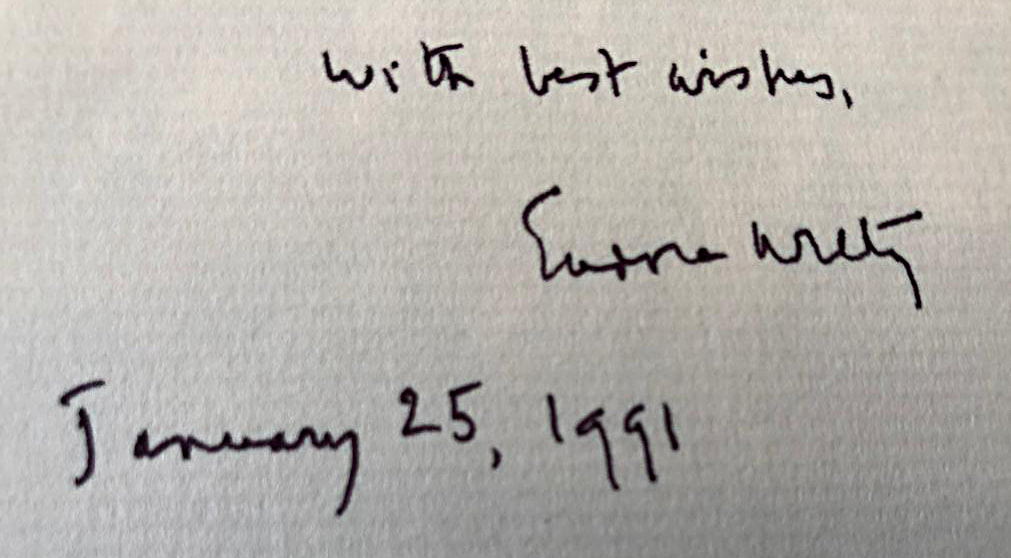

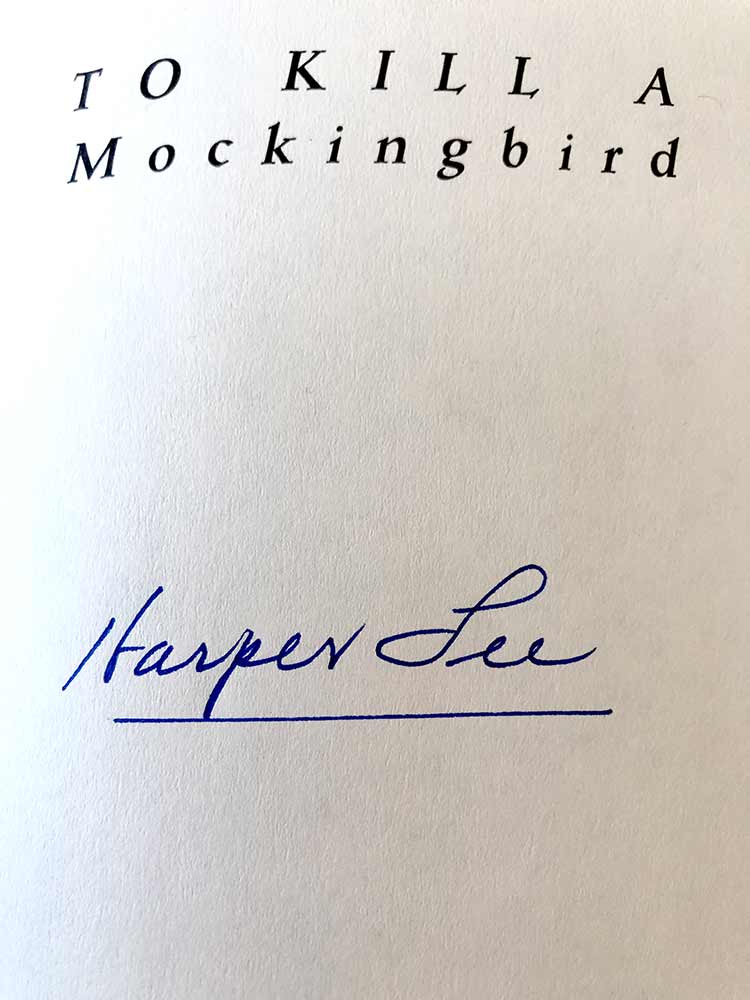

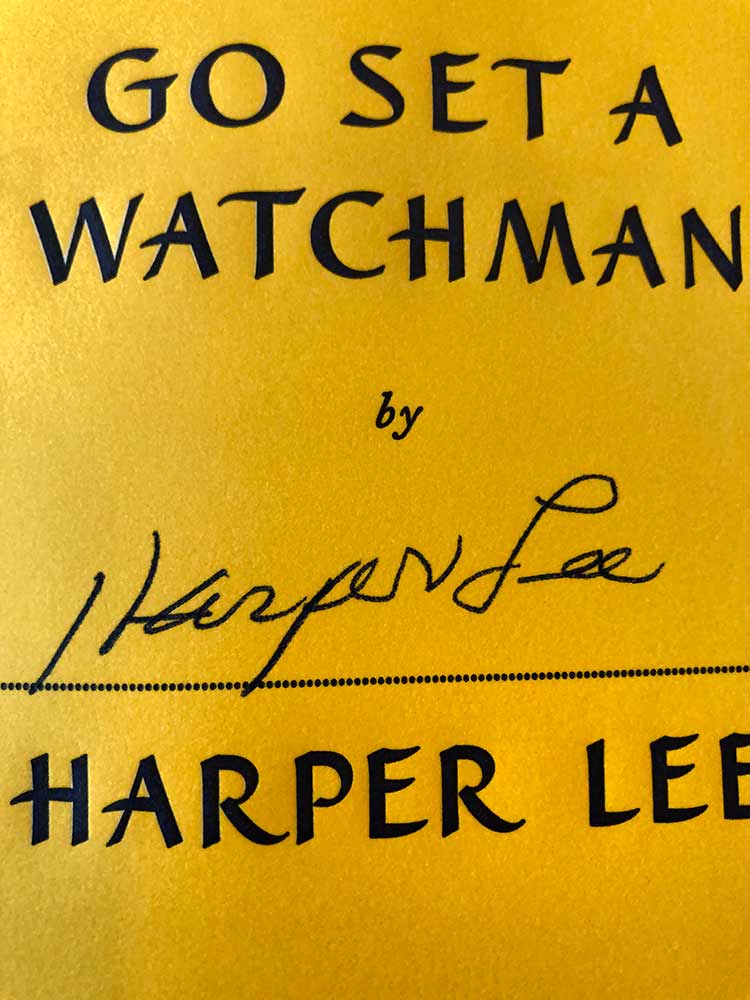

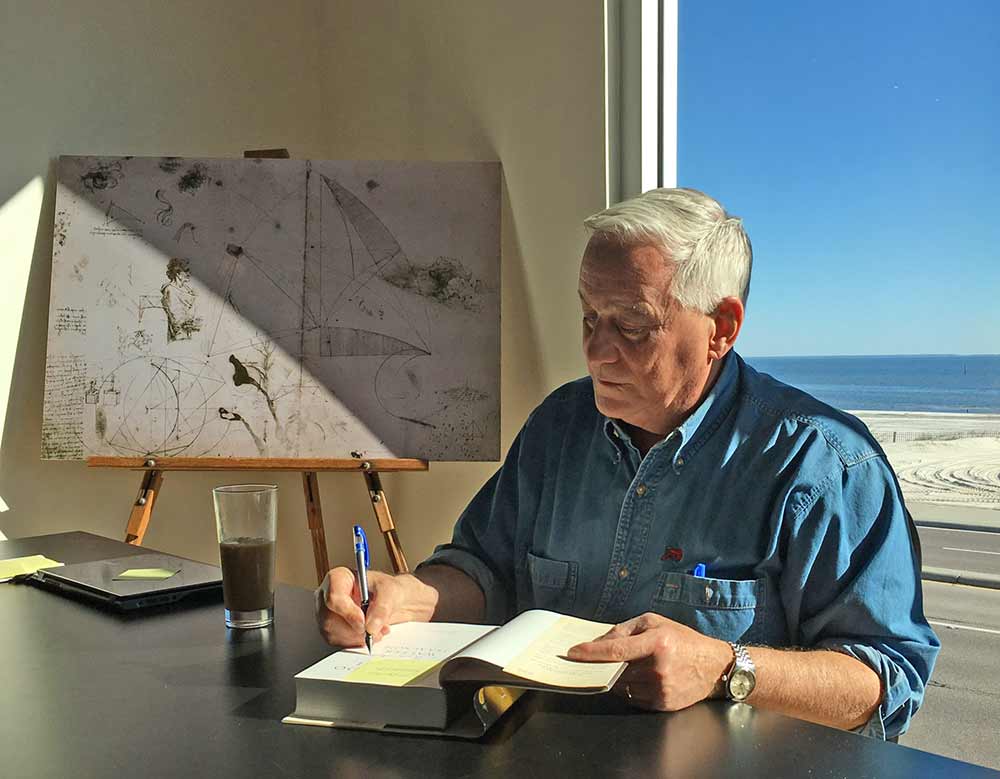

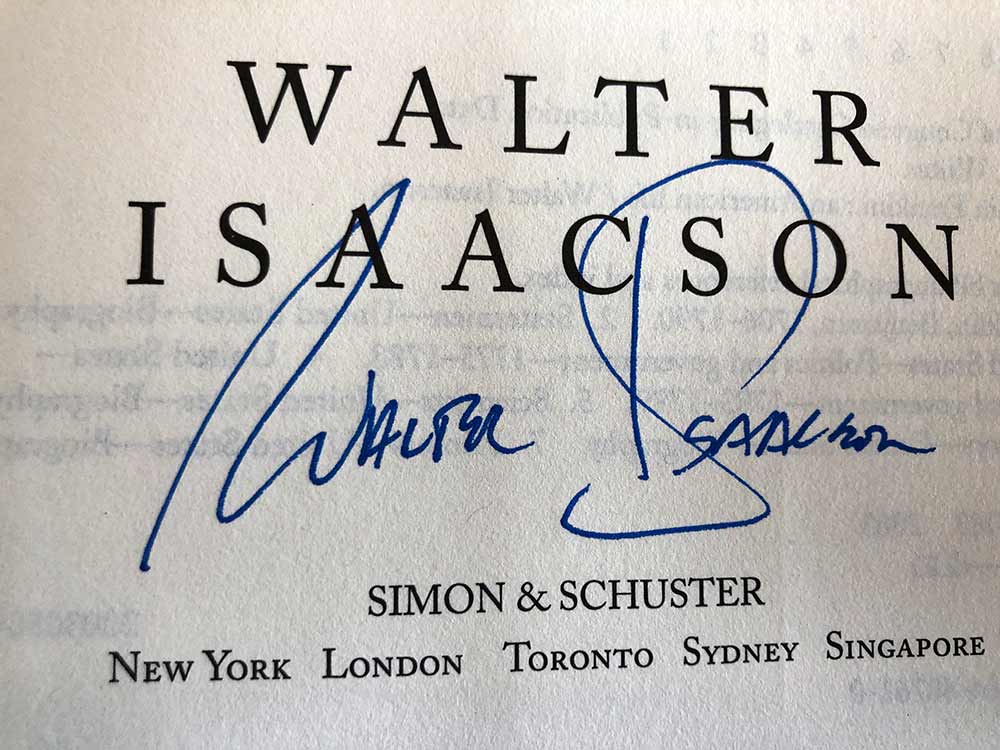

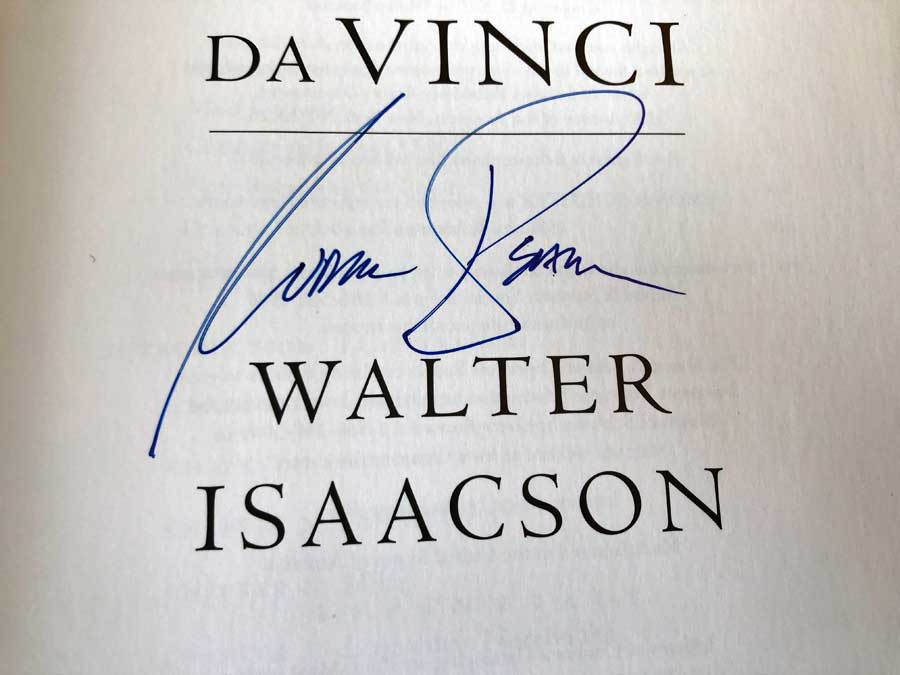

With an effective work of fiction or nonfiction, a bond forms between the reader and writer during the many quiet hours of reading. Often, a reader, if the prose is elegant and insightful, will connect emotionally, enhancing the perception of a personal connection with the author. A signature is a physical manifestation of this intellectual bond. A successful author may sign thousands of books over the span of a career, sometimes hundreds within the span of an hour or two at a well-attended book-signing event. Would a writer, and who would blame him or her, grow weary of the repetitiveness of signing, eventually cutting corners with less precision, not crossing the “t” nor closing the loop of the “o”? I looked first to Eudora Welty to analyze two of her signatures, one done early in her career and the second at the very end. Eudora Welty was born in 1909 and lived most of her life quietly in Jackson. In 1941, her first work of fiction, "A Curtain of Green," was published. Welty won the Pulitzer Prize for "The Optimist’s Daughter" in 1973. She died in her Jackson home near Belhaven College in 2001. In August of 1949, Eudora Welty signed a copy of her recently published short story collection, "The Golden Apples." Her signature is small, taking up very little space on the free front endpaper of the book. It is 4 inches long and 1.5 inches high. The letters are rounded, not sharp, and the full signature is somewhat illegible. Advancing to 1991, Welty signed a copy of "Photographs," a 1989 collection of her black and white photos from the 1930’s taken during her employment by the federally funded Works Progress Administration. Undoubtedly, she had signed thousands of her books from the time of "The Golden Apples." The signature again measures 4 by 1.5 inches. The letters remain loosely connected, flowing as if part of an undulating wave. She crosses the “t” in Welty differently than before. From "To Kill A Mockingbird," Harper Lee’s 1960 tale of race and class in the mid-twentieth century Deep South, the author’s signature is straight, neat, and underscored with a dash. Each letter is clear, nearly perfect in execution. Just prior to her death in 2016, HarperCollins published Lee’s second novel, "Go Set A Watchman." She signed very few copies of either of her books. Lee’s signature in Watchman is exceedingly scarce. Health took its toll on her autograph, not repetitiveness, since she rarely signed her books or appeared in public. By 2015 when Watchman was published, she had suffered a stroke and resided in an assisted living facility in Monroeville, Alabama. It is painful to look at Lee’s later signature when compared against an earlier version forty years prior. It is a scrawl, jagged and uneven. Slow and deliberate, determined, I assume, to push through and finish, it is an act of will on Lee’s part to sign her name. Still, it is lovely, when one thinks of all she has survived. “I’m still here, damnit,” it announces. I detect little difference in best-selling author Walter Isaacson’s 2003 signature between "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life" and his 2017 "Leonardo Da Vinci." He is a studious, accurate, and gentlemanly scholar and it is reflected in his graceful and elegant signature. But, back to Jesmyn’s original question: had her signature changed over the years? I believe it has. In 2008, "Where the Line Bleeds" was published by Agate Publishing in a trade paperback format. The initial print run was small and Jesmyn, a first-time author, was relatively unknown. Her signature is rolling, free, fresh, unbounded, gushing across the page. After dozens of national and international honors, including two National Book Awards, seemingly endless book tours, and several thousand autographs, Jesmyn’s signature on her 2017 novel, "Sing, Unburied, Sing" is somewhat shorter in length. It is a bit more bold, sure-footed, proud, resting on the page, I feel, as a literary placeholder in American Letters. It is in motion as if it wants to run off the page into the liminal space where Jesmyn sources her creativity. I’ve watched hundreds of authors sign their work. My sense is that each is proud that a reader cared enough to ask for a personalization of his or her novel or non-fiction work. The author is in the moment with the reader taking pride in signing. Art, including literature, is about connecting us through an imaginative work. A signature brings it into the tangible moment, fleetingly, yet ironically, eternally.

In the writer's open letter to the author of this compelling book, he explains why he cannot review it.

- story by Scott Naugle, photos by Patrick O'Connor

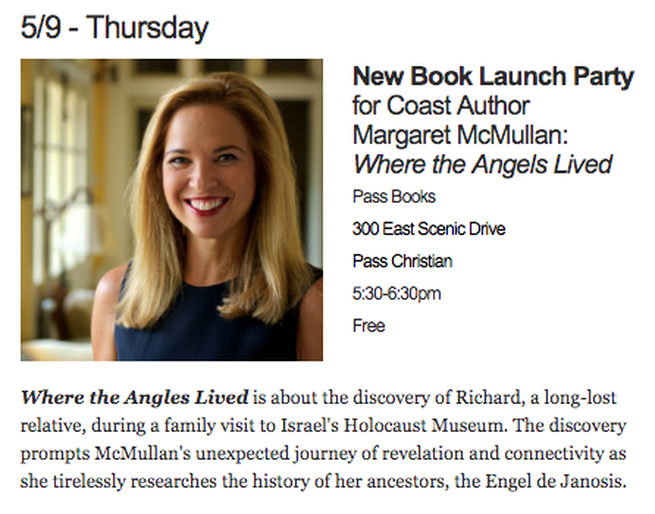

Dearest Margaret,

It was almost fifteen years ago that I first reviewed and wrote about one of your books, “How I Found the Strong,” for a literary magazine. Your family’s history, on your father’s side, was the impetus for the young adult novel. While we were friends at the time, we’ve become closer. I consider your family an extended family – your mother Madeleine, husband Pat, and your son James, whom I still can’t believe the years have passed so quickly that he is graduating from college next weekend. You’ve hung up on me during phone conversations and slapped a cellphone out of my hand when I was texting and driving (you were right to do this, even underscoring it with adult language). For these reasons, I struggled with whether I would have the professional distance to review and discuss “Where the Angels Lived”. How could I pass judgement on the intensely personal and compelling work of a close friend? Transparency is always the correct approach, so if I am asked to review your most recent work, I’ll be transparent about our long friendship. I wanted you to know this. Your love for your family, past and present, and their histories appear to be a consistent motivation for your intellectual work. “How I Found the Strong” was inspired by a long-lost manuscript, “The Life and Times of Frank Russell.” Frank Russell was the great-uncle of your grandmother on the McMullan side and dictated his remembrances of life in Smith County, Mississippi. As you recollected in the novel’s afterword, “the part of Frank’s story that interested me the most, however, was what he did not talk about.” A historical detective, you used the facts at hand and created the story of the young fictionalized Frank Russell into an award-winning novel. A few years later, in 2008, you visited the Holocaust Museum and learned of a relative you had never heard of – “Richárd.” The museum archivist looked at you and declared, “Look at me, you are the first to ask about him. Do you understand? No one has ever asked about this man, your relative, Richárd. No one ever printed out his name. You are responsible now. You must remember him in order to honor him.” As the curious and impassioned intellectual I know you to be, you had no choice but to learn more about Richárd Engel de Jánosi. Like the nonfiction manuscript of Frank Russell that you spun into a beautiful novel, you were presented again with a previously unknown, and hidden, piece of your family’s history. The story of Richárd Engel de Jánosi is so incredible, though, that a nonfiction exhumation of your family’s story through research is the appropriate platform. Life is stranger, and far more brutal, than fiction. But against what may be the safe or prudent thing to do, in a Hungary that remains deeply anti-Semitic, you traveled to ask questions about a Jewish uncle that you never knew existed nor was ever acknowledged in any way. You met resistance, both official and subtle. As I turned the pages of the advance copy of “Where the Angels Lived” that you were kind enough to give me a few months ago, I feared for your safety. As you recollect in “Where the Angels Lived”, “Never heard of him,” your mother snaps when you ask about Richard. “You must have it wrong. I don’t have time for this.” Madeleine McMullan hangs up.

Richárd was the son of your great-grandfather, Adolf, as your research in Hungary revealed. Adolf created a vast business empire of land-holdings, lumber, and coal by his mid-thirties. He started without a penny and succeeded despite the anti-Jewish legislation in Hungary. He had to pay “tolerance taxes.” You speculate, “Maybe he was granted immunity as a Jew because he took such good care of his mostly Catholic workers. He built them homes, schools, bathhouses, and churches. He paid for their teachers and priests.”

All of this began to fall apart in the years leading up to 1944. And while many members of the Engel de Jánosi family sent their money to Swiss bank accounts, converted to Catholicism, changed their names, or took the opportunity to leave the country early, Richárd, strong and quietly defiant, resisted. One of the most beautiful passages in your book is when you use your considerable talents as a novelist to bring Richárd to life for us from the few facts about him: “He looks to be the kind of relative I would have loved – tall, distant, cool. The quiet type, pensive and precise. I would have tried to make him laugh… He looks so sure of himself, even a little defiant, stubborn. Maybe too proud. Maybe he believed too much in his own decency, maybe that’s what got him killed.” What you later learn is that your mother, at the age of ten in April 1939, was spirited from Hofzeile, the family estate, at night with her mother, your grandmother, Carlette. “My mother wore a dark blue coat several sizes too big so that she could grow in to it. My mother had the red measles, which had spread into her eyes. [My grandmother] told my mother not to look back, to never look back.”

Later, as the train was stopped at the border crossing, “the German fear of germs” prevented the officers who boarded the train from entering the cabin where your mother suffered. “Carlette slid the papers under the door… They kept their gloves on… held the documents at the corners” and quickly stamped them.

Learning all of this was too much for you. Against your grandmother’s advice to your mother eighty years ago, you had looked back. “Sitting there in the pew carved of Moravian oak, I start to shake. I curse every last Hungarian who deported or murdered my family. See, Look at me. My mother got out and she had me and I had a son. You didn’t end us.” Richárd, as you learned, stayed and administered the family businesses until he was met at his front door “by a black car with swastikas on the doors.” He was loaded onto a cattle car and taken to the concentration camp in Mauthausen. Your mother never discussed the Hungarian side of the family, instead selectively acknowledging the French lineage of her mother’s side. You found and communicated with the only other living member of the Engel de Jánosi family of your mother’s generation, Anna Stein. Recovering from your father’s death and healing from a new hip, your mother was willing to return to Europe in 2013. As your mother and Anna meet, you reflect that “Keeping secrets kept them alive, but that’s also how they lost contact with their families… They both know how to suffer and they both know how to worry… It’s the living they sometimes have trouble with.” After the visit with Anna Stein, you boarded a bus with your mother and she begins to cry, “Her weeping becomes guttural, the same sound she made the day my father died. Her slight shoulders shake and she puts her head into the crook of my arm. She is crying for everything and everyone – her dead husband, her father, her mother, her lost family and country. She is crying for herself and for all those in her family she knew and never knew.” And this Margaret, my dear friend, is what I have to tell you in this long letter – I won’t be able to review “Where the Angels Lived” if asked. It’s too close. It’s emotional – and yet, in the end filled with hope and love and leaves me with a sense of a future for humanity because of what you did. I cannot add words or commentary to something so beautifully lived and written. With much love, -Scott

“Where the Angels Lived: One Family’s Story of Exile, Loss, and Return”

By Margaret McMullan Calypso Editions ISBN: 9781944593087 $19.95

Books may be ordered (and shipped, if requested) here.

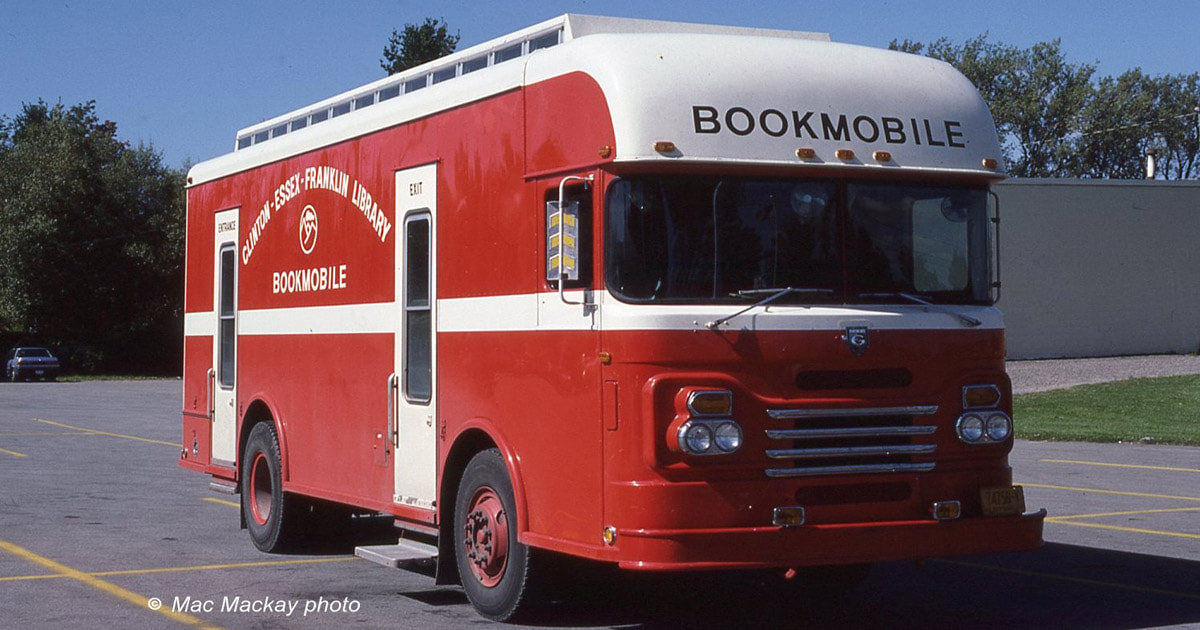

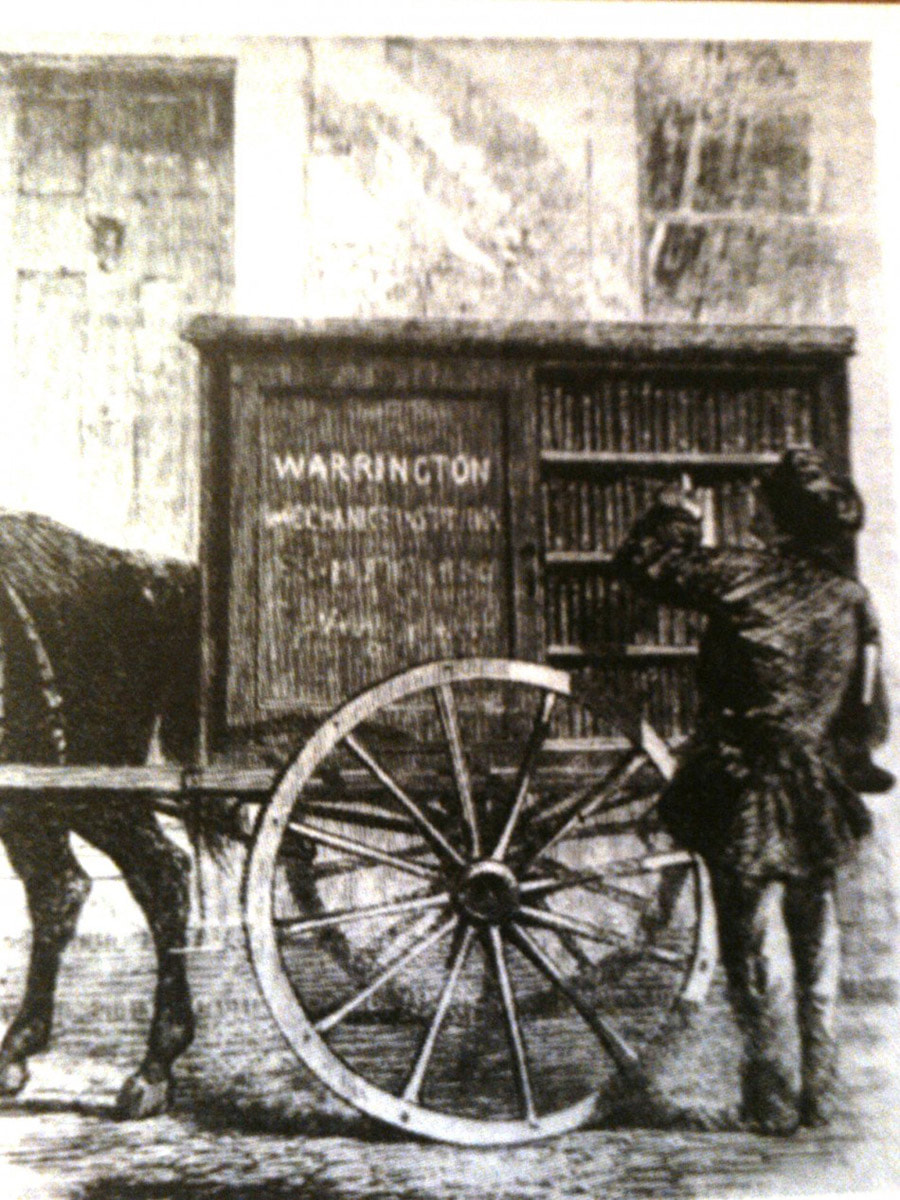

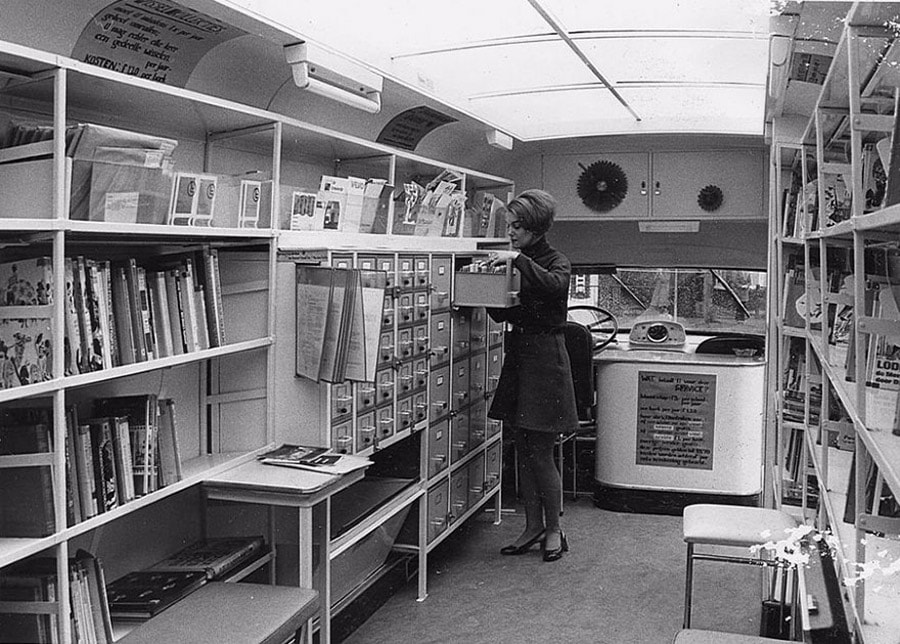

These four wheels transported books to readers - and readers to untold adventures.

- story by Scott Naugle

Davidsville remains a small community in western Pennsylvania. It was founded in the 1830s, German stock, dairy farmers, and a dry town, not by law, but because it was considered prudent to avoid spirits. The Lutheran church at the top of the hill at the eastern bend on Main Street recently celebrated its dodransbicentennial (175 years). My relatives from the early eighteenth century are buried in its cemetery.

Main Street, logically, is the main thoroughfare. In the winter after a heavy snowfall, it had just the right slope to serve as our sled-riding racetrack. After it was plowed, scraped clean and salted, we moved to the cemetery to ride our sleds in the deeper and fluffier snow. Too young to know it then, but this was only the first in a lifetime of blasphemous acts on my part. A bookmobile is a vehicle, often a truck, and nowadays possibly a tractor trailer, designed for use as a library. Books are transported to readers, often in rural or underserved areas, encouraging reading, engagement with ideas, and literacy. The first bookmobile, or horse-drawn book cart, dates to 1839. It was a frontier traveling library in the western United States, established by the publishing house of Harper & Brothers, known in the present day as HarperCollins, one of the world’s largest publishers. Like so many childhood memories recalled through a hagiographic lens, I assumed that the Somerset County Bookmobile was a thing of the distant past. Fortunately, I checked. The big red creaky behemoth, dually tires on the rear, has been replaced with a long bright heavy-duty truck, green, blue, and bright, with large lettering shouting BOOKMOBILE. Literature still rolls among the Appalachian Mountains of Southwestern Pennsylvania. Among the many pleasant memories of childhood, those connected to reading and books are most vivid. I easily recall the two steps up through the tall bi-fold doors into the bookmobile as big ones for a young lanky boy. Once inside, it was a paper cocoon of hardback books, shelved spines out, with the identifying Dewey Decimal number easily visible taped on the lower outside edge. There was order in this little bus, comfort, tidiness, with a small card catalog as a guide. All questions and conversations were whispered to the librarian/truck driver. She had a small desk attached to an interior half-wall behind the driver’s seat. I’ll call her Mrs. Blough, because that was likely her name if it wasn’t Mrs. Kautz. No more than four books were to be checked out for two weeks. As a matter of pride, I imagined, Mrs. Blough always had her date stamp prepared to two weeks in the future and a moist ink pad at the ready. She precisely stamped the due date on the glued card in the back of the book and underscored it by chiming, “this book is due back on August 4th, 1968. There are fines if it is late.” Over the summers I read through Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, The Hardy Boy Mysteries, and the crime-solving of Encyclopedia Brown. By my preteen years, I discovered Thomas Paine and The Age of Reason, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus from this faded red bookmobile. Bram Stoker’s Dracula could only be properly read late on a hot summer night. Stoker’s writing style oozes succulent prose deepening the darkness of midnight reading under a small bedside lamp while building suspense, horror, and trepidation for the appearance of the dark, flowing cape of the titular, fanged vampire. Four books a week was a tad light for me even at nine years old. I was able to read eight a week once I convinced Mrs. Blough that I was also checking out books for my mother. To legitimize the additional four books, I wrote them on a notecard before entering the bookmobile. I pulled out the list after obtaining the first four books I wanted and then pretended the books listed on the notecard were for my mother. Honestly, I never felt that I was fooling Mrs. Blough. My mother was unknowingly the best-read adult in Davidsville. Serendipitously, the bookmobile always parked in front of Main Street Bakery. A stack of books, chocolate milk, and a warm cinnamon-sprinkled donut and I was content. Would life ever be better than this? When the scheduled two hours had passed, Mrs. Blough would secure the rear and side doors, then climb behind the large steering wheel. Sitting stiffly upright, hair tightly pulled up into a peppery gray bun, she would depress the clutch and crank the engine. While grinding the engine into first gear, Mrs. Blough, librarian and truck driver, steered our bookmobile onto Main, popping the clutch as she headed north over curvy, hilly roads to the afternoon stop in Stoystown.

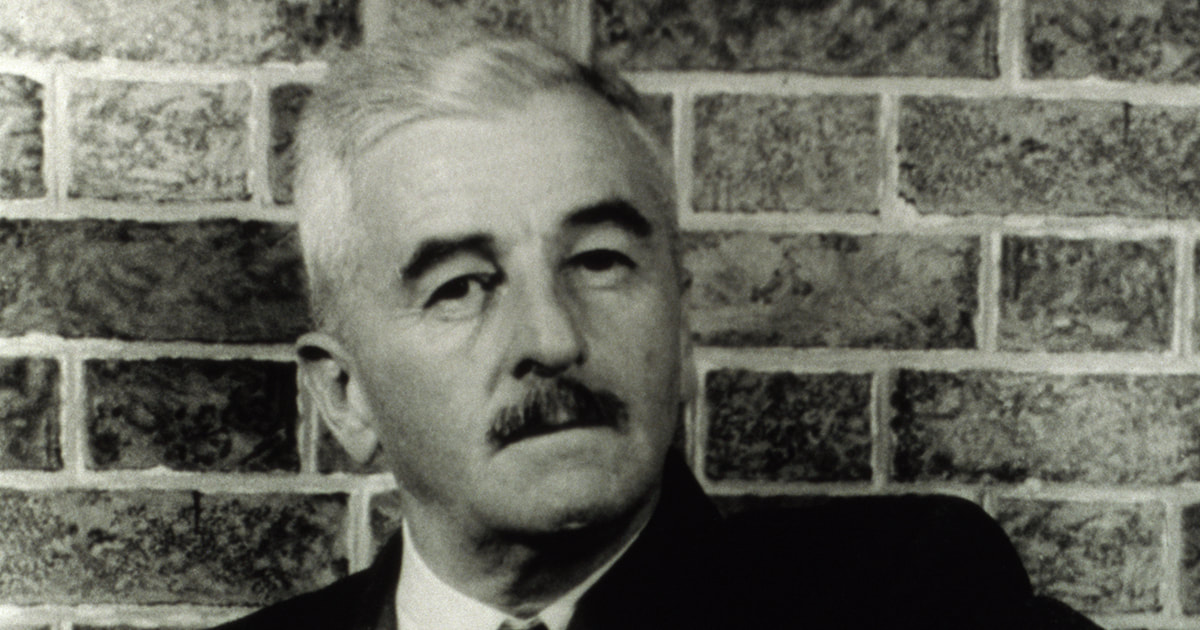

As a professor, writer Scott Naugle taught more than literary criticism; he allowed his students to read for the sheer joy of the written word - even Faulkner.

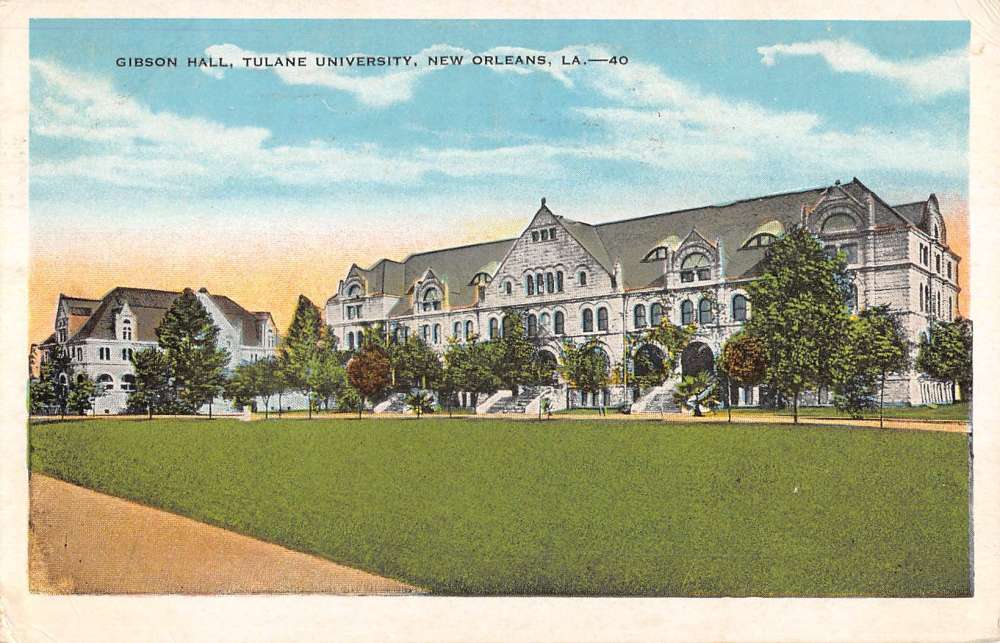

Through a clerical oversight, I’m sure, my “Reading the Modern South” class was scheduled in Gibson Hall. Gibson Hall faces St. Charles Avenue overlooking Audubon Park.

The oldest structure on campus, it was built in 1894 in the Richardsonian Romanesque style. Thousands of massive chiseled stones create an impressive façade exuding intellectual gravitas. The office of the university president and his staff occupy the lower floors of the building. The students arrived on time for the first class. Several carried clean, crisp notebooks while the remainder snapped open laptops. There was an almost equal number of men and women, nine in total, all either juniors or seniors, anxious survivors of the undergraduate milieu. We bantered a bit, I believed it important that they be relaxed with me, and then I handed around the course outline. Streetcars slid by outside the large windows, the clattering barely audible. Here is what I wrote in the syllabus and read aloud that evening: I commit to work with you in developing a set of critical analysis skills as you read literature. These skills include close reading, methods to critically analyze the text, comfort with literary vocabulary and terms, identification of historical and cultural issues, and several tools to interpret texts. You are encouraged to speak your mind in class and to write beautifully and convincingly in support of your thoughts. On that hot, humid night in early June as I discussed the course novels and supporting material we would read and write about, there was an audible group groan when I mentioned the inclusion of William Faulkner’s Light in August. Silence. And then I asked why. “We’ve read Faulkner in another class and the professor couldn’t explain the novel, but acted as if he could, and talked a lot. It was torture. No more Faulkner, please.” All shook their heads in agreement looking directly at me to gauge my response wondering, I assume, if they had crossed a line.

***

I experienced a flashback at that moment to two years earlier when I was a graduate student in a class on literary theory. We read Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, a beautiful and haunting novel if left unmolested by forced interpretations through various lenses of theoretical conjecture.

Literary theory attempts to offer avenues to understand a work of fiction through culture, historical forces, or the functioning of the psyche, among other approaches. Specific types of criticism include New Criticism, Structuralism, Deconstruction, Feminist Theory, and Marxism, among a salad of many others. The professor, let’s call him Dr. Wheezy, coached us each week to view Bronte’s work through a specific type of theory. It was Feminist Theory one week and then Cultural Materialism the next. Rather than enrich the reading of the novel, it became a series of weekly calisthenics in reductivism, marginalizing a beautiful work of literature into a constricted cardboard box. As an example, a weekly assigned reading was Terry Eagleton’s Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontes. The novelist Francine Prose, in Reading Like a Writer, recalls her experience in a graduate seminar as a student, “That was when literary academia split into warring camps of deconstructionists, Marxists, and so forth, all battling for the right to tell students that they were reading ‘texts’ in which ideas and politics trumped what the writer had actually written.” I vowed at that moment, should I ever be fortunate to teach, that I would work with students to read with delight, insight, and to marvel in the beauty of the written word.

***

In contemplating the syllabus for the course, my desire was to show different ideas and cultures within what is mistakenly perceived as a stagnant, singularly-minded South. We studied Thomas Hal Phillips’ The Bitterweed Path, about gay love in the mid-twentieth century rural South. Phillips was a closeted Mississippian and Republican political operative.

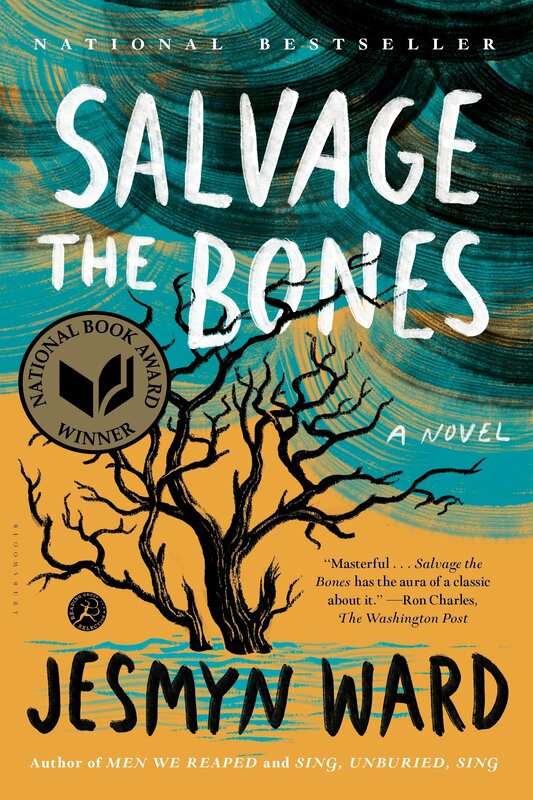

Uncle Tom’s Children by Richard Wright was included as a window into the hatred of the last century and the different, yet still as vigorous, forms it takes today. Shirley Ann Grau’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Keepers of the House was a springboard for discussion about our changing values and the hypocrisy of racism. To bring the readings into the present day, we read the marvelous Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning Salvage the Bones. I don’t know how and even if it is possible to measure success, but several students voluntarily wrote their end of semester research papers on Light in August.

Cradled in the Colorado Rockies with a menagerie of animals, author Pam Houston comes to terms with her past and finds strength in her surroundings.

- story by Scott Naugle

Author Pam Houston will sign books and speak about her new memoir, Deep Creek, at Pass Books, 300 E. Scenic Drive, Pass Christian, on Thursday, Feb. 21, 6pm - 7pm. Click here for more details.

Houston recounts and contextualizes her struggles from a childhood of physical and mental abuse by both parents forward through decades of introspection, eventually locating a measure of peace and happiness in the present day. She sourced both therapy and solace from a large ranch in Northern Colorado, high in the Rocky Mountains, near the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

Many know Houston from the best-selling Cowboys Are My Weakness, her work as a columnist for Outdoor magazine, or the collections of short stories. She is currently the Director of Creative Writing at University of California, Davis and travels the world mentoring at writer’s workshops. Houston unearthed her uphill, rocky footpath to a mountainside respite after years of agonized wandering, “… and so my mother died, drunk and unhappy, and I found my way to this ranch, where I protect and am protected by animals, this place where nature controls how I spend my days and how I spend my life, this place where I can love every season.” The four-legged menagerie loved by Houston includes Icelandic sheep, dogs, mini-donks, horses, cats, and a short visit by an orphaned baby elk. Within all the moments of pure joy the animals inspire, there are also notes of sorrow. “In 2014 I lost Fenton Johnson the wolfhound,” she recounts. Houston was out of town leading a writer’s workshop when she received word of Fenton’s failing health. She returned home immediately by air, landing in a Denver snowstorm. “The weekend was everything all at once. It rained and snowed and blew and eventually howled, and I slept out on the dog porch with Fenton anyway, nose to nose with him for his last three nights.” The story of Fenton was an emotional one for me, striking close to home. I recently lost Snopes, a feisty, gnarling, grumbling, old, five-pound poodle, an ever present companion in charge of the house for the past ten years. When I received the call that Snopes was dying, I stood helplessly in chilly air on a concrete sidewalk corner outside of the office at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. I am consoled by the fact that he died in the arms of the only other person who loved him as much as I did. It was a Sunday mid-morning in Pass Christian several months ago and Pam Houston sat down beside me in a green upholstered armchair. She held her coffee in a white porcelain cup, silently, absorbing, watching the sunlight sparkling and bouncing off the undulating Gulf water. The previous evening, a whisper before midnight, I listened in awe as Pam stood in a parlor just up the street on Scenic Drive, ten or so others sprinkled around the room, reciting a long poem, one that she explained had moved her. I’ve forgotten the poem, but the passionate recitation mesmerized me. I was taken by someone so soulfully enthralled with emotion and ideas as conveyed through poetry. Now, she leaned toward me in the light-washed room and asked what I thought of Hunger. “It is one of my favorite novels,” I blurted. “Several years ago I read through all of Knut Hamsun’s work.” My response, judging by the expression on her face, initially appeared to puzzle her and then slowly changed to one of slightly bemused understanding. What kind of a person responds with an obscure Norwegian novelist’s work, a Nazi-sympathizer from the last century, when at that moment Roxane Gays’ Hunger: A Memoir of Body was at the top of the bestseller list? Houston gently corrected me. “In spite of the encroaching darkness, there’s nothing out here to be afraid of,” Houston recalls in Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country before a late day walk on her property. “Coyotes are not brave enough to attack a full grown woman and a 150-pound dog, even a whole pack of them. Mountain lions hunt at dusk and dawn, but in this country, there’s never been an attack on a human. A black bear won’t be hanging around on the riverbank, but even if he were, he’d hear us before we’d hear him and hightail it back into the forest.” There’s not much of anything, two-legged or four-legged, that Houston is afraid of any longer. Houston’s depth of insight and barebones honesty, her fluency and descriptive agility with the written word, brings Virginia Woolf to mind, ruminating in A Room of One’s Own: “The whole of the mind must lie wide open if we are to get the sense that the writer is communicating [her] experience with perfect fullness. The writer, once this experience is over, must lie back and let [her] mind celebrate its nuptials in darkness.”

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country is a memoir of strength, resilience, and love. It’s an affirmation of life, a “nuptial” unifying beauty with honesty, a Rocky Mountain transcript of Woolf’s ideal. I hope that Pam Houston permits herself a moment of celebration.

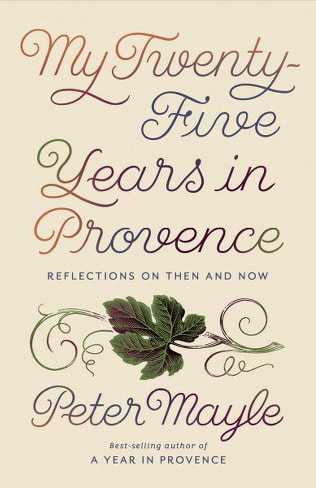

A new book by Peter Mayle - My Twenty-Five Years in Provence - has the power to transport a book lover back to the banks of the Seine decades before.

- story by Scott Naugle

I can tell you where I bought almost every book I own, but few purchases were as memorable as the one from a bouquiniste over the River Seine in Paris, France.

In My Twenty-Five Years in Provence: Reflections on Then and Now, Peter Mayle transported me across several decades and more than a thousand miles to my Junior year in college studying International Economics at the University of Nice in the South of France.

Readers were first introduced to Peter Mayle twenty-five years ago through his best-selling A Year in Provence. The book chronicled his first year of living in Luberon, in Southern France, after a successful career in Great Britain as an advertising executive.

Then and now, Mayle’s descriptive and convivial prose is a leisurely stroll through Provence:

“Where else does the sun shine for three hundred days a year? Where else do you find the truly authentic rosé, sometimes fruity, sometimes dry, a taste of summer in the glass? Where else is goat cheese an art form?” After a week of classroom and studies in Nice, my weekends were free to explore Southern France, and occasionally, to trek a bit farther. A Eurail Pass was not only an overnight train ticket to Paris, Barcelona, or Rome, but also an inexpensive sleeping berth for a frugal college student (at least one who preferred to save his money for buying books).

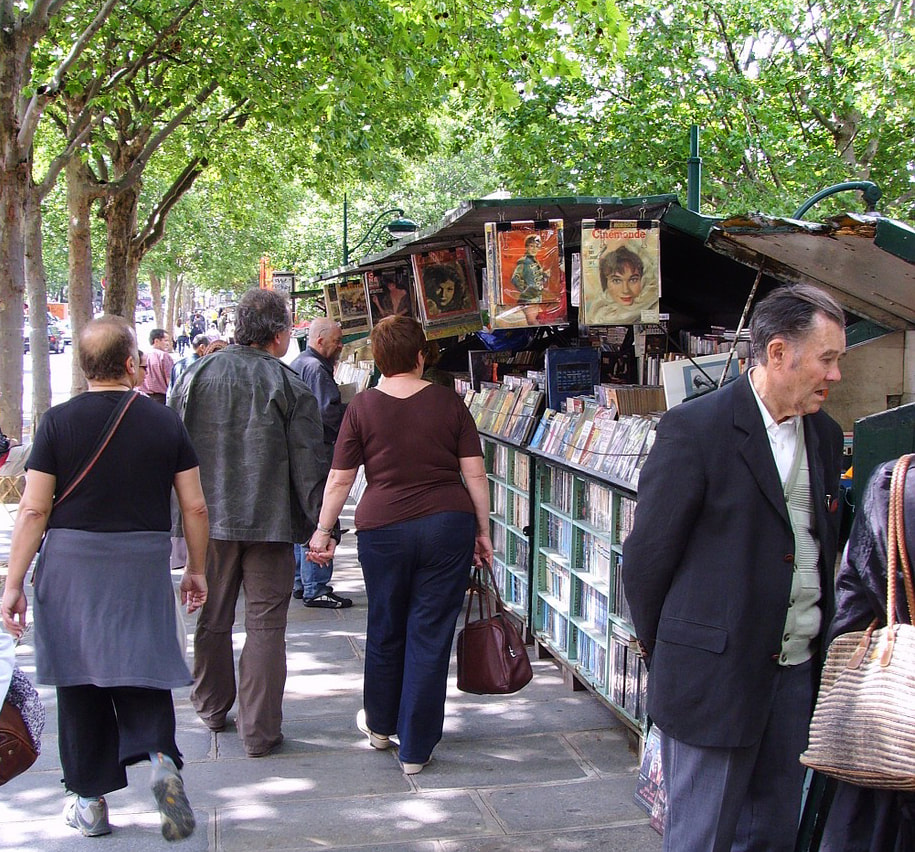

I found a youth hostel to drop my bags on the Ile de la Cité, an island in the middle of the River Seine in Paris and began walking in the early Saturday morning daybreak. It was then that I discovered the bouquinistes on Le Pont Neuf, opening their charming small stalls, fussily preparing for a day of hawking their wares. Le Pont Neuf is a bridge dating to the sixteenth-century connecting the island to both the Left and Right banks of Paris.

A bouquiniste is a bookseller working from a small green permanent stall, either along the banks of the Seine River in Paris or from one of the bridges crossing it. Their storied history as booksellers dates to the sixteenth-century. In the evening, the stall is closed and locked. A recent count listed over 200 bouquinistes collectively offering almost 300,000 books.

The smell of freshly baked pastries, gesticulating Frenchmen excitedly attempting to draw passersby's to their stalls, the imperceptibly flowing Seine below, dark and mysterious, and in the distance the gargoyles perching, patient as if waiting for a call to mission, on the flying buttresses of Notre Dame Cathedral, as I was overwhelmed, blissfully catatonic for several minutes, deciding which heightened sense to explore. Eventually, I walked to a stall and negotiated a price for a volume of Moliere’s plays.

It must have been the appeal of the book itself, gold embossed title and edition, on the white hardback cover, a small 1925 printing about the size of a moderate slice of dacquoise, that prompted my purchase. I still have the volume of Moliere’s plays.

Thank you, Peter Mayle, for carrying me back to France and reminding me that “to see a ten-acre field of lavender in full bloom is to see one of the great sights of summer. And if nature isn’t enough, there are dozens of centuries-old villages, often built on hilltops, that are rarely without their artistic admirers…”

I finish writing this on a deck in Pass Christian overlooking the Gulf of Mexico; again, the gentle pulsing of water, animated conversation in the background, and dozens of shelves of books behind me. How else would one want to create a treasured book memory?

Pack your bags AND your books. Writer/bookstore owner Scott Naugle doesn’t leave home with them.

Writing in The Unpunished Vice: A Lifetime of Reading, Edmund White shares a similar sentiment, “If I watch television, at the end of two hours I feel cheated and undernourished (although I’m always being told of splendid new TV dramas I haven’t discovered yet); at the end of two hours of reading, my mind is racing and my spirit is renewed. If the book is good…” Edmund White is a novelist, biographer and essayist. His fiction includes The Beautiful Room is Empty, The Farewell Symphony, and Fanny: A Fiction. He has penned biographies of Marcel Proust and Jean Genet. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1940 and resides in New York City. Employing his remarkable and voluminous memory, White recounts his reading and the impact of the works on his life and world view as he matured from teenager to septuagenarian.

White recalls his first reading of William Faulkner, and credits him with “expand[ing] his concept of the novel” as an art form while also performing as social commentary. He checks Faulkner though on his “verbal, seemingly drunken absurdities” as demonstrated by this phrase, among others, from Absalom, Absalom, “That aptitude and eagerness of the Anglo-Saxon for complete mystical acceptance of immolated sticks and stones.”

I packed The Unpunished Vice for a recent flight to Washington, D.C., connecting through Atlanta. Traveling with books requires planning. I spend far more time fussing over what I want to take along to read than I do with tossing a few clean shirts and socks in a Samsonite. My luggage invariably holds two or three books, more if the trip is longer, and one or two in my backpack that I carry on the plane.

Non-fiction is a more convenient read while traveling, preferably a book of essays such as White’s. Literary fiction necessitates longer periods of uninterrupted thought. A fifteen or twenty page essay is ideal for the short hop from Gulfport to Atlanta.

Once, I made the error of packing five books, including two hardbacks, in my suitcase. I was pulled out of the airport security line by a TSA agent after “suspicious objects” were detected in my suitcase that I just placed on the conveyor belt to move through the scanning machine.

“I need you to remove all the books that are in your suitcase,” bellowed the brusque TSA agent. His sallow skin matched the worn brown of his stretched polyester pants as he attempted to impart an air of authority by a wider than natural stance while crossing his arms.

“Why?” I asked. “You may have hollowed out the insides of the books and placed prohibited or dangerous substances in them. It’s not normal to have that many books in a bag.” Advanced age teaches me to hold my tongue, but not my thoughts. “Oh, ok," I said while thinking, Yes, the books do contain dangerous things. They are called ideas. When no incendiary chemicals were found in the books, with a wary eye, the deflated TSA agent waved me through. I don’t fare well either at times in the seat mate lottery. On a more recent flight, while reading The Unpunished Vice, ensconced in words and intriguing thoughts, Flem Carbuncle (I don’t know if that was his name, but it fits) sat beside me, overfilling the narrow seat.

“What's that there you're reading? A book?”

“Yes,” I said curtly. “My grandmother was from up north there in Tennessee and she wrote a little book once before she died,” he blathered, oblivious to the fact I was not fully listening. “Oh, that’s interesting.” “The little book was about the pixies and faeries that she believed visited her at night in her sleep and gave her advice when she was upset or worried.” Contrary to the title of White’s book. I felt I was being punished for my vice of reading. Aloft, the clouds thousands of feet below, after the stewards and stewardesses have docked the beverage cart and my overhead reading light is the one beacon in an otherwise dark cabin on a red eye flight, I think of this passage from a letter written by Virginia Woolf to a friend, “Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.”

When writer/bookstore owner Scott Naugle begins to pack his library, he finds he's not the only book-lover to be transported by the task.

- by Scott Naugle

When the writing, fiction or nonfiction, connects with me at the deepest intellectual and emotional levels, often decades ago, so too does memory include the physical surroundings, the room, the chair, the palpable sense of reading that specific book.

A book is not read in a vacuum, but rather it is a sticky, intellectual syllabic immersion into the limbic region of the brain, where memory is stored, dense and nuanced with smell, touch, sight, and sounds.

In Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions, Alberto Manguel notes a similar cognitive connection: “The books most valuable to me were private association copies, such as one of the earliest books I read, a 1930’s edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Many years later, memories of my childhood drifted back whenever I turned the yellowed pages.”

In the year 2000, Manguel and his partner purchased a medieval presbytery in the Poitou-Charentes region of France, renovating it into a personal library and home. In 2016, he was named director of the National Library in his native Argentina, necessitating the crating and moving of his extensive collection.

A few months ago, at an age when I should be downsizing rather than upsizing, we purchased a home, originally constructed in 1885, meticulously renovated to its original state, heart pine floors, beadboard ceilings, and white porcelain doorknobs, with, of course, the necessary 21st century upgrades including oversized bathrooms and a gas stove top (I’m staying away from the contraption) with enough jets to launch a small aircraft. Manguel writes elegantly and passionately about packing and shipping 35,000 books overseas. I only moved 5,000 books less than two miles down East Second Street in Pass Christian. I’m a minnow to his white whale.

To carefully box for the short journey, I pulled a four-volume set of Edgar Allan Poe from the shelf. It was already old and loose in its binding when I purchased it for a few dollars at a flea market over forty years ago.

“There are few persons who have not, at some period in their lives, amused themselves in retracing the steps by which particular conclusions of their own minds have been attained,” wrote Poe in The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Rereading it in the present, I was transported back to Somerset County, Pennsylvania, on a snowy January evening. Pushing midnight, I was sitting upright in bed on top of the tan and blood red striped bedspread in my bedroom, the fingers of the frigid winter air creeping in through the loose wooden window frame, rattling it when the snowy wind whooshed against it. The room was illuminated by the single bulb in my gooseneck reading lamp, casting menacing shadows on the far wall, as I turned the pages. Downstairs, the late local television news was droning on, the imperceptible words of the stern newscaster like a distant wailing. Again Poe, “Madmen are of some nation, and their language, however incoherent in its words, has always the coherence of syllabifaction.”

A few weeks ago, during our humid August, I packed several books by and about Toni Morrison. In The Bluest Eye, I had marked this passage, “Each night, without fail, she prayed for blue eyes. Fervently, for a year she had prayed. Although somewhat discouraged, she was not without hope”

I was transported to my study in Jackson, Mississippi, first reading this novel twenty-five years ago, sitting in a green leather recliner, the white Berber carpet contrasting sharply with the blue walls. Beignet, my small black poodle, was sleeping against me. It was a Sunday afternoon and I just finished several hours of working in the yard. The sun beamed through the double window at an angle with the effect that one half of my study was brightly lit while the other half remained in dusky blackness. It was as if a solid impenetrable line separated the two parts of the room into opposing worlds. Morrison’s use of language, the subtext, and how subtext overwrites a facile and simple interpretation of a story, captivated me. It was as if I was learning to read again for the first time. As Morrison explains in a series of essays, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, I would discover years later, “In other words, I began to rely on my knowledge of how books get written, how language arrives; my sense of how and why writers abandon or take on certain aspects of their project… of a kind of willful critical blindness.” From The Bluest Eye: “Outside, the March wind blew into the rip in her dress. She held her head down against the cold. But she could not hold it low enough to avoid seeing the snowflakes falling and dying on the pavement.” Every reading of this passage then and now is weighted with my guilt at not doing enough to destroy the unfairness thriving in our world.

I’m in the present, late October, relaxing for the first time in the upstairs library, early evening, in our new home. The two poodles, Gonzo and Snopes, are asleep. Glancing around the room, my eye snags every few seconds on a title, memories of how the book made me feel in a time and place of the past, how each informs my sense of self.

Jorge Luis Borges’ Collected Fictions rests behind me on a high shelf. From his short story The Library of Babel: “When it was announced that the Library contained all books, the first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure.”

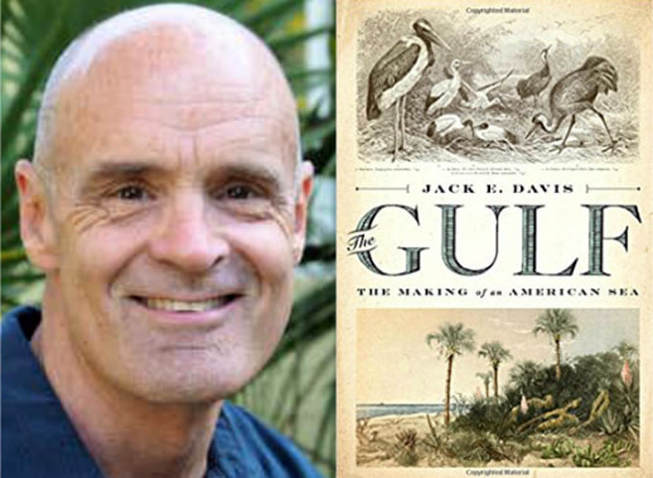

A sweeping new narrative explores the Gulf of Mexico, taking readers from its exotic pre-history to its precarious present.

- story by Scott Naugle

Davis continues with a foreboding close to the paragraph, “The doomed megafauna struggled for survival against a common implacable predator – humans with spears and shell clubs – and against a changing climate. Lost causes both, as it turned out.”

Between his opening comments on the plate tectonics forming the Gulf of Mexico and the present day, Davis tells a rip-roaring, relevant, concise, beautifully written history of the gulf. He is a polymath covering every aspect from early twentieth-century visits by the painter Winslow Homer and poet Wallace Stevens; Spanish, French, and English exploration; the dawn of commercial fishing; the advent of tourism; and the BP oil spill.

Jack Davis spent a lifetime preparing to write this monumental work. He recalls his childhood romping on the beaches and marshes along the coast of the Florida panhandle, studying the birds while listening to the melodious rhythm of the surf. He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of South Florida and a doctorate from Brandeis University. Davis currently teaches environmental history and sustainability studies at the University of Florida.

Davis was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for History for The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.

While the research is meticulous and expansive ranging from social history to wildlife and the coastal flora, it is the narrative, the people and story of the gulf, bringing this history to life like a multi-layered novel. “Among the most scintillating of sights were fish in schools as long as freight trains, running with the invisible gulf tide” was the scenery encountered by Winslow Homer in 1904, as he traveled with “rod and reel … and paints and brushes” as described by Davis. A century later, Joseph Boudreaux, earning a meager living as a commercial fisherman, lamented over the effects of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, erosion caused by commercialization and inland effluents, and the unnatural effects of levees and dams, “that’s when the erosion’s going.”

Davis explicates, “If you were a fisher, every day was a day not unlike the heron that fished the marsh - a quest to make the quota for sustenance.” The gulf, over-used and exploited, has exceeded its quota, depleted and polluted. We are modern-day versions of our ancestors with “spears and shell clubs,” employing instead rigs, nets, and chemicals against the gulf.

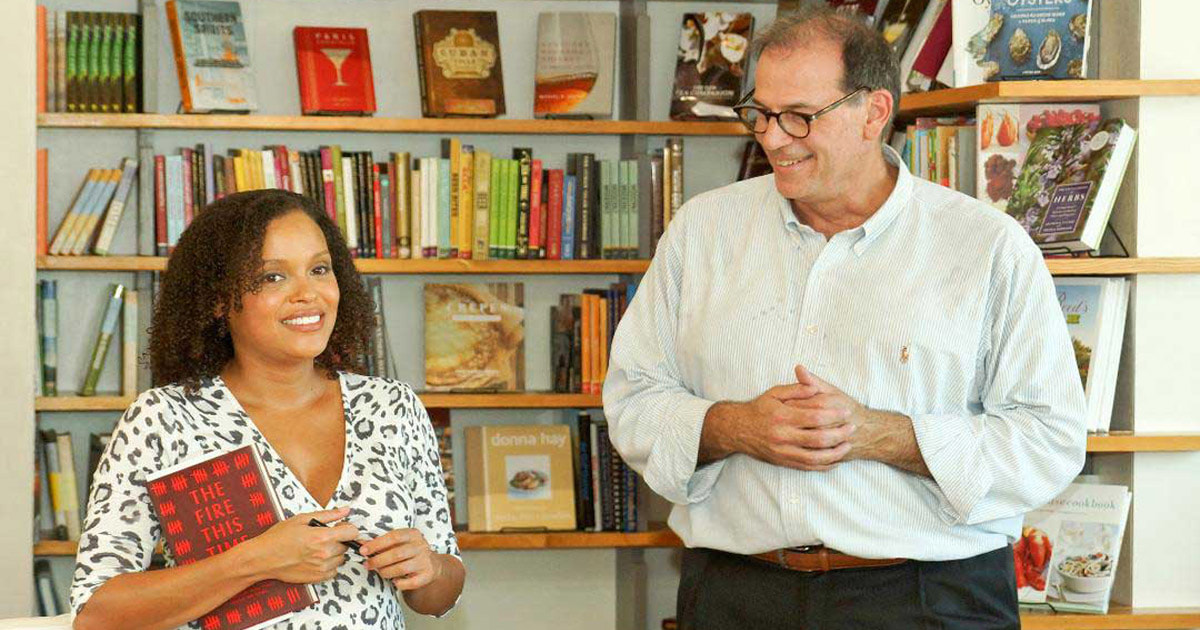

The Gulf is the 2018 selection for One Book One Pass, a community reading initiative where everyone reads the same book and has the opportunity to hear the author speak. In 2016, the first year for the program, Erik Larson spoke about the best-selling “Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania.” Last year, National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward discussed “The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race,” a collection of essays edited by Ward.

For Larson and Ward, the community turnout was both overwhelming and enthusiastic. The Randolph Center in Pass Christian was stacked to standing room capacity to hear each author speak and answer questions about their work.

The date for this year’s presentation by Jack Davis is Wednesday, October 17th 7:00 PM at the Randolph Center, 315 Clark Avenue in Pass Christian. It promises to be another informative and fascinating evening.

While dealing with a serious illness, writer Scott Naugle finds his path to recovery leads down a garden path.

Mid-March, I pushed the wheelbarrow, gripping it as my makeshift walker, slowly and falteringly struggling toward the botanical patient. A few weeks out of my second surgery within two months, withered and lame, I was intent on defying the surgeon’s orders to remain in bed.

From my earliest memory, gardening has always been therapy, my green recovery room, where I locate a peaceful respite, sweating the tension away with the swing of a scythe, lopping back the Hedera covering and obscuring the earth as well as ensnarling my disposition. Eschewing traditional physical therapy, I was determined to regain strength under the warming sun surrounded by azaleas, caladiums, and elephant ears. Gardening is an experience appreciated by many whether digging in the dirt, planning the plantings, or exchanging notes about foliage follies. In “Onward and Upward in the Garden,” a collection of Katherine White’s garden columns for “The New Yorker” magazine, husband E.B. White, author of the children’s classics “Charlotte’s Web” and “Stuart Little,” wrote of his wife’s respect for the hard labor of planting and weeding: “She refused to dress down to a garden: she moved in elegantly and walked among her flowers as she walked among her friends – nicely dressed, perfectly poised. If when she arrived back indoors the Ferragamos were encased in mud, she kicked them off.”

Katherine White’s essays both criticize and applaud seed catalogs. She notes that the horticulturists and hybridizers who assemble the annual seed catalogs are “individualistic – as any Faulkner or Hemingway, and they can be just as frustrating and rewarding.”

White highlights Atlee Burpee and Joseph Harris for what the seedsmen are doing to zinnias in their catalogs. She aims a critical thorn at Burpee for “devot[ing] its inside front cover to full-color pictures of its Giant Hybrid Zinnias, which look exactly like great, shaggy chrysanthemums. Now, I like chrysanthemums, but why should zinnias be made to look like them?” White is in a snit and having none of this genetic tinkering. I imagine she may have removed a Ferragamo and tossed it across the room. Duck, E.B. I lowered myself to the ground at garden’s edge close enough to the Hydrangea so that I could clip and debulk the detritus with a surgeon’s precision, preserving anything green showing signs of healthy regrowth. The coarse cool sandy soil gently scraping against my knees, after weeks of starched white sheets and bleached hospital gowns, sent a rush of warming bliss through my body. I was in touch with the earth again. In the collected letters between two gardening friends, “Two Gardeners: A Friendship in Letters,” Katherine White and Elizabeth Lawrence share their lives, illnesses and births, within letters framed by the latest bulb discovery or the best positioning for a cyclamen in the sun. An inquiry from one correspondent to the other may begin with, “My next question is to ask whether you happen to know the title of any recent books on flower arrangement?”

Lawrence and White are a smidge high-minded for me, graciously formal and exacting, while writing to the other on gardening. I’ve never been able to pronounce the botanically accurate names of plants that both toss about effortlessly – Cluisiana, Marjolettii, acuminata, and Oxalis bowiei. Either my tongue is too heavy or I have a mental block in verbalizing words that sound foreign for something simple and natural, a tulip bulb, or I possibly cannot conceptualize of the odd alignment of consonants and vowels.

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei is my cancer. I cannot pronounce it either. Henry Mitchell, writing in “One Man’s Garden,” approaches the garden with much of the same jovial, yet no nonsense approach as I, “If tender folk go to pieces for fear a plant may be hurt (even before it is hurt, and it usually isn’t) then how do they cope with the death of dog or person? We are not born to a bonbon-type life, you know.”

Mitchell was the longtime garden columnist for “The Washington Post.” His humorous articles focus on planting and growing in small spaces, the two hundred and three hundred square feet patches serving as beds, behind Capitol Hill and Georgetown brownstones.

On my hands and knees, moving slowly and gingerly, I aerate the soil surrounding the Hydrangea. The wooden handle of the small hoe is worn smooth from years of gripping, weeding, rejuvenating with it. I lay on a heavy dose of fertilizer while feeling the healing sun for the first time in months. For a moment, it is silent and still. There’s no gulf breeze. I know to my core that if the Hydrangea can recover, then so too will I. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed