Common Ground

A small shrine to Our Lady of the Woods has become a touchstone for two girls' schools - together spanning more than a century and a half.

- story by Ellis Anderson

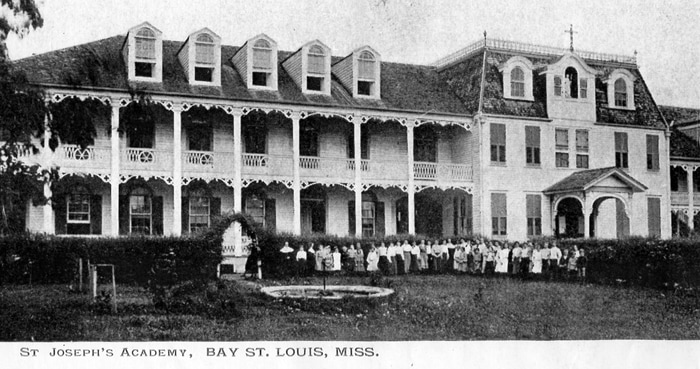

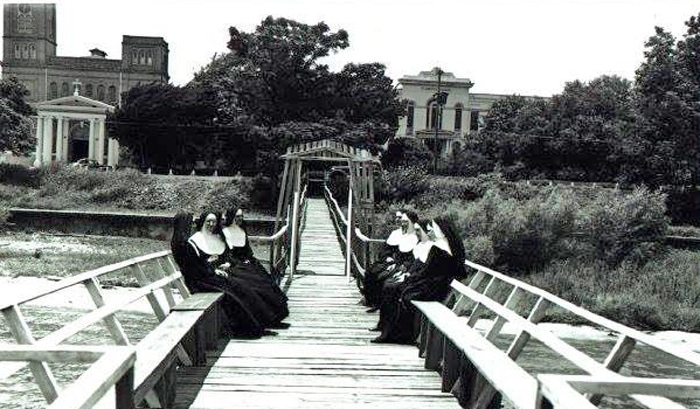

The grotto was built in the 1860s on the grounds of St. Joseph’s Academy, a parochial girls’ school that was just a few years old at the time. St. Joseph’s was started by three hardy French nuns who made the journey across the Atlantic for just that purpose. Classes filled immediately.

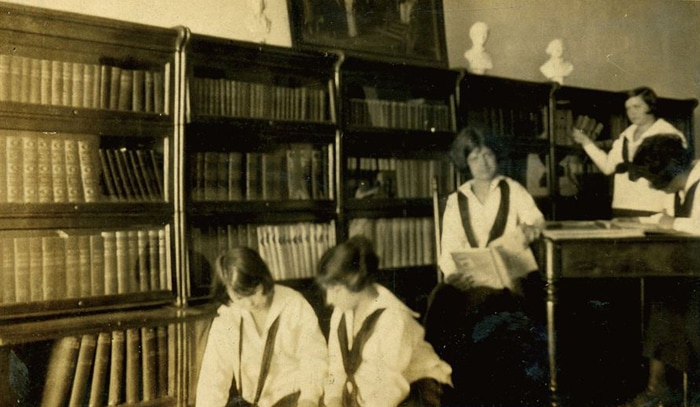

According to an excellent article on the Hancock County Historical Society’s website, the presence of the nuns heartened Father Buteux, the pastor of Our Lady of the Gulf Catholic Church. He wrote about their arrival with great enthusiasm in his 1855 diary. Bay St. Louis then was a primitive village. Living conditions would have been Spartan, even by standards of the day, without conveniences like electricity or running water. Yellow fever and other diseases were always a threat. Yet three more nuns arrived the following year. By the 1860s, when the shrine was built, the school began to offer boarding facilities. Board, tuition and washing (of clothes, presumably, not students), cost parents $220 annually in 1867. The grotto was built after a perilous trip Father Buteux made, sailing from France back to the States. Caught in a violent storm that sheered the mast from the schooner, the priest promised to build a memorial to the Blessed Mother if she would spare the ship and its passengers. In those early days of the city, the shrine was set deep in the surrounding woods. St. Joseph’s Academy continued to grow through the years, gaining a national reputation for scholastic excellence. Unfortunately, an enormous fire ravaged much of the town and destroyed the school and the church in 1907.

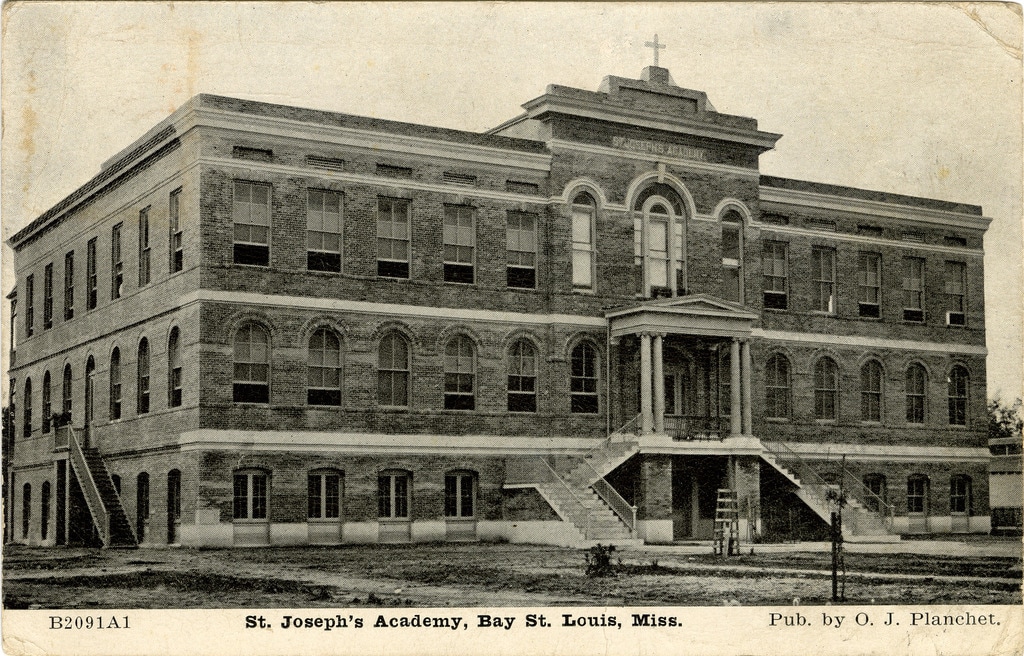

The plucky nuns rallied with wholesale community support and found funding to build a new school. They and their students moved into an elegant new three-story building in 1908. In 1924 a companion two-story brick building was constructed. Referred to as the gymnasium, it was used for music and other classes as well.

The ultimate demise of St. Joseph’s came from a scarcity of teaching nuns rather than a diminishing student body. The front building that had been built in 1907 was torn down after the school was closed in 1967. According to one graduate, it was an act that came as a shock to the town’s residents and the alumni who cherished the architectural treasure. The gymnasium was destroyed by another fire a few years later. Hurricane Camille in 1969 scoured the grounds. The Our Lady of the Woods shrine was all that remained. A campus that had been one of the prides of the coast no longer existed. And local parents who wanted a parochial education for their daughters had to look elsewhere.

Then, in the aftermath of Camille, a local attorney with four daughters kick-started a drive to establish a new girls’ school at the site of the former. The late Michael D. Haas teamed with the pastor of OLG, the late Msgr. Gregory J. Johnson and Brother Lee Barker, who was principal of St. Stanislaus College prep school at the time.

Haas’s wife, Myrt, calls herself the original naysayer of the project. When the idea was first discussed, she found it difficult to believe such a grand dream could be brought to fruition. But her enthusiasm quickly caught fire. She remembers that the concept had instant “wholesale community support.” Many obstacles had to be surmounted. For instance, the group discovered the new school couldn’t receive accreditation without a science lab, a library, or language courses – things that seemed out of reach with their limited funds. But Father Lee offered to share the facilities at St. Stanislaus, an unprecedented move. Co-educational programming between the all-boys school and the female students at St. Joseph’s had never before been considered. “Our girls learned a lot from the experience,” says Myrt, laughing. “For one, they learned to put on lipstick before they went over to the St. Stanislaus campus.” Myrt says that the main reason the school succeeded was the good attitude of the early students. In those early days, they didn’t have the resources that the public schools did. For example, there was no cafeteria, considered a school basic. “I give the students credit for sticking with it and making it work,” Myrt says. “Those girls made it happen as much as the parents and teachers.”

Current OLA principal Darnell Cuevas, who’s been at the school’s helm for two years, says that the school’s enrollment is nearly up to pre-Katrina levels now, with more than 250 students. The students are excelling academically as well. In 2017, 38 graduates scored in the top tier on standardized college entrance tests and were awarded nearly $5 million in scholarships.

The Our Lady of the Woods grotto has become a historical and spiritual tie between the two academies. It’s a favorite place for group photographs of students, teachers and St. Joseph’s graduates, who reunite often. In May of this year, more than 40 students and teachers from the final class of 1967 gathered for their 50th reunion. The grotto was a favorite meditative spot for Cuevas, even before she began as principal, and she’s eager to see that her younger charges learn the history of the shrine. Both Myrt and Cuevas speak fondly of the legendary caretaker of the shrine, Sister Albertine, who kept the grotto tidy and with a candle burning at its base around the clock, throughout the year, for decades. Myrt tells the tale of wartime sacrifice that kept Sister Albertine from performing her duties. “During World War II, enemy submarines were patrolling the waters of the gulf,” says Myrt. “We had blackouts every night. Lights had to be turned off in houses and buildings. Even cars couldn’t drive the coast roads with headlights.” “The Coast Guard came to St. Joseph’s, saying that they could see the candle at the foot of the shrine more three miles out in the gulf. Sister Albertine had to stop lighting the candle. But just for the time being.” Citizen Scientists

From tracking Monarch butterflies, to counting birds, to monitoring water quality, volunteers of all ages are helping make a difference through the Citizen Science program coordinated by the Pascagoula River Audubon Center.

At the end of the story, you'll find info about the Hancock County October bird count and learn how you can help! - story by Lisa Monti

The Pascagoula River Audubon Center connects people to nature through its citizen scientist program, headed by Erin Parker. The center offers monthly training on different topics at no cost involved except the $8 admission to the center for non members.

You don’t need a scientific background, just an interest in our coastal resources and creatures that share it with us. “We do the training for you,” said Parker. The most time you’ll spend is three hours per month.

Like bird watching? Sign up for the National Audubon Society's Christmas Bird Count, the longest-running citizen science project that started in 1900, or monitor the birds on our front beaches during migration seasons.

If you’re interested in the water quality where you live, volunteer to help scientists keep tabs on our waterways. There are two in Hancock County that are monitored monthly: Magnolia Bayou near the Yacht Club and Watts Bayou. The testing sessions take about an hour to complete.

“Anyone can be a citizen scientist, from a kid to a senior. They are able to contribute regardless of experience,” Parker said. “The equipment is pretty minimal and the protocol is pretty straight forward.”

Volunteers learn first hand about the natural world and get the satisfaction of knowing they are contributing data so we can get a much fuller picture of what’s going on in the world. Find more information about the center and the volunteer opportunities at http://pascagoulariver.audubon.org or email Parker at [email protected].

Audubon Coastal Bird Survey-

Hancock County Fall 2016 Schedule Washington Street Pier, Bay St. Louis-Hancock, Audubon Coastal Bird Survey Site Description: This site has a sandy beach shoreline, ending at Washington Street Pier, which has rocky jetties on either side. Reddish egrets, ruddy turnstones, and a variety of plovers and sandpipers are common on the mudflats directly adjacent to the jetty. The opposite side of the road has mature live oaks and suburban yards which attracts common suburban passerine species such as mockingbirds, crows, and blue jays. Meeting location: Washington Street Pier and Boat Launch. There is ample parking available near the pavilion. ACBS Site Coordinator: Judy Reeves, [email protected] (Note: Contact ACBS Site Coordinator to participate and verify schedule) Schedule: Tuesday, October 18, 2016 7:00 AM--8:30 AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 7:00 AM--8:30 AM Ladner Pier, Waveland, MS-Hancock, Audubon Coastal Bird Survey Site Description: This site has sandy beach on either side of a large pier, with rocky jetties on either side. Reddish egrets, Ruddy turnstones, and a variety of plovers and sandpipers are common on the mudflats directly adjacent to the jetty. The opposite side of the road has mature live oaks and suburban yards which attracts common suburban passerine species such as mockingbirds, crows, and blue jays. Meeting location: Ladner Pier (parking area) 125 N Beach Blvd, Waveland, MS 39576 ACBS Site Coordinator: Barbara Bowen (602) 319-0538 or [email protected], (Note: Contact ACBS Site Coordinator to participate and verify schedule) Schedule: Friday, October 14, 2016 7:00 AM-8:30 AM Bayou Caddy, Bay St. Louis, MS-Hancock, Audubon Coastal Bird Survey Site Description: This site has a sandy shoreline, and many artificial pilings, jetties, and structures. On the other side of the quiet street, you can often see a variety of blackbirds on the power lines. There is also a marsh system across the street, where bald eagles and a variety of herons and egrets are often seen. The sandy shoreline generally has large groups of small shorebirds foraging on the tide line. The artificial structures have gulls, pelicans, and terns. Meeting location: Silver Slipper Casino (parking lot), 5000 S Beach Blvd, Bay St. Louis, MS 39520. Ample parking is available. ACBS Site Coordinator: Ned Boyajian, [email protected] (Note: Contact ACBS Site Coordinator to participate and verify schedule) Schedule: Monday, October 17, 2016 7:00 AM 8:00 AM Buccaneer Beach, Waveland, MS-Hancock, Audubon Coastal Bird Survey Site Description: This site mostly consists of a seawall, with limited areas of sandy shoreline. Many jetties and artificial structures exist, where pelicans, eagles, ospreys, terns, and gulls perch. The shorebirds are condensed onto the small patches of sandy shoreline. The opposite side of the road has many perching birds of all varieties on mature vegetation. Some sections have productive marsh habitats, so marsh birds such as herons, egrets, sparrows, and wrens are common. Meeting location: Corner of Forest Street and South Beach Blvd, Bay St. Louis, MS 39520. Limited parking available on the shoulder of the road. ACBS Site Coordinator: Ned Boyajian, [email protected], (Note: Contact ACBS Site Coordinator to participate and verify schedule) Schedule: Monday, October 17, 2016 9:00 AM 10:00 AM *To sign up online to become Audubon Volunteer, please visit us at https://app.betterimpact.com/PublicOrganization/fb88f60d-ae22-4234-a99a-51c2607450d9/1

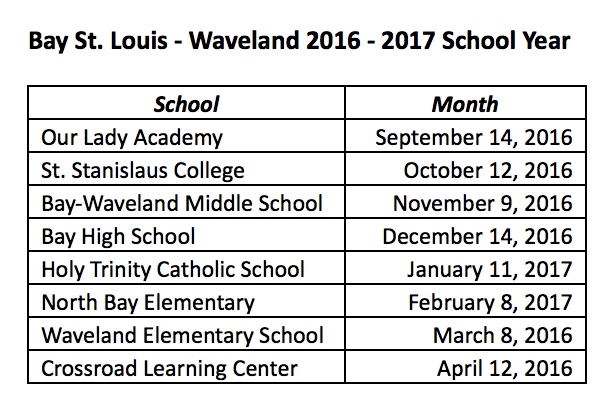

This month, the Bay St. Louis Rotary announces its 2016/2017 teacher recognition schedule, 94 OLA Students Make Top Scores and Bay High Makes an "A."

During the meeting the principal is asked give a brief overview of the nominated teacher and why they were chosen. If the teacher desires to, they may share any additional information with the club. Each teacher is given a certificate and a gift card to one of the local restaurants as a small token of appreciation. Rotary’s motto is “Service above self” and the teachers of the community uphold that motto.

Bay St. Louis Rotary Club's School Recognition Schedule for 2016/2017OLA Recognizes 94 Students Scoring in 90th Percentile or Above

|

| Say congrats to Rotary Teacher of the Year, Tarah Herbert, and the graduating classes in Hancock County - Hancock High, Bay High, St. Stanislaus and Our Lady Academy! | Honor Roll |

Bay High's Herbert Named Rotary Club of Bay St. Louis' Teacher of the Year

A Bay High teacher for the past five years, Herbert received her degree from USM in 2011. Since then, she has consistently achieved certification in computer graphics programs to stay current with quickly evolving technologies and to pass that knowledge on to her students.

Herbert teaches Digital Media Technology and Graphic Design courses, including overseeing the Tiger News Team. Herbert has developed the team to be an almost completely student-run club, where students write, film, produce and present news stories daily for the school. The team has recently begun expanding their reach into the community, helping document and promote non-profit events, including Rotary's Chili Cook-off fundraiser. In addition, Herbert sponsors various school clubs at Bay High and stays active and involved in campus life. This May 2016 Shoofly Arts Alive story details some of her work.

Rotary selects a Teacher of the Month from a local school based on their commitment to excellence in education and dedication to engaging students and encouraging high performance. From the monthly honorees, the Rotary Club selects one Teacher of the Year to honor each spring.

271 Hancock High Graduates Soar

Besides college scholarships, Hancock students were honored with many academic, leadership and community awards as well. Hancock High acknowledged students chosen for the prestigious Hall of Fame. Students were recognized for academic achievements such as Mississippi Scholars, Honors and Highest Honors as well as the Valedictorian and Salutatorian.

70% of the senior class received scholarships and 85% received awards. These accomplishments were honored on Night of the Scholars on April 28, and Senior Awards night, May 16 and culminated in the Graduation Ceremony on May 20.

Hancock High School also continued their tradition of a senior parade in their cap and gowns at each of the elementary schools on May 6. The long celebrated tradition of Senior Assembly was held on May 13 with the community gathering to celebrate the seniors and then the junior class moving to take their place as the seniors departed the assembly.

For some of the Hawks of the Class of 2016 the journey to college will be close as they continue their education at our own community college - Pearl River (PRCC). Others will stay in Mississippi attending Belhaven, Millsaps, Mississippi College, Mississippi State, University of Mississippi, University of Southern Mississippi, William Carey and others. Still others fly further from the “nest” attending Brown, Harvard, University of Melbourne, Vanderbilt and others. Three of the Class of 2016 graduates have chosen to serve our country - the community and our nation are grateful.

Parents, family, friends, faculty and staff of Hancock County School District celebrate the accomplishments of each of these students as they venture out. Each prepared for what their future holds.

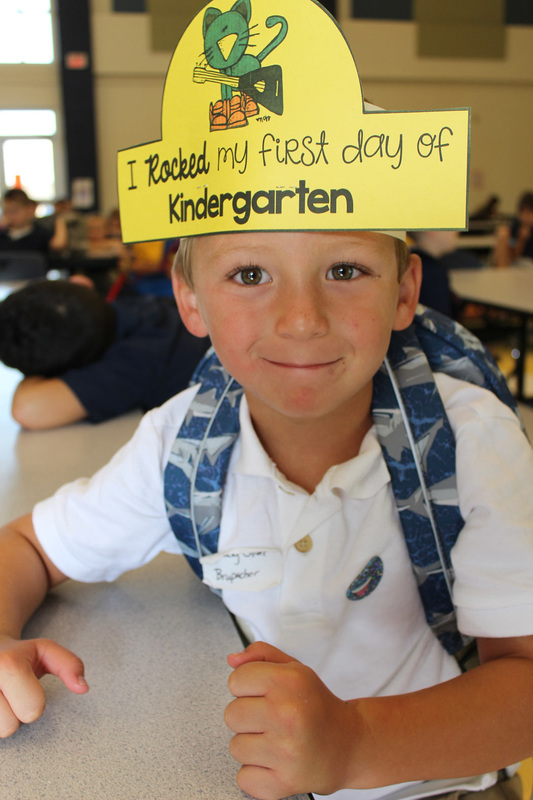

Superintendent Alan Dedeaux shared, “I am grateful to the faculty and staff in Hancock County School District for preparing these students to go forth and be successful. From the moment they join us in kindergarten until they cross that stage – we are getting them ready to achieve great things!”

Hancock High School, principal, Tara Ladner, added, “I am so very proud of every student – I cannot imagine how proud their amazing parents must be. I am grateful to be a part of this community.”

111 Bay High Seniors Earn $10 Million+ in Scholarships

“The Bay High School class of 2016 has a personality, work ethic, determination, poise, sense of humor and sense of self that any person would adore,” said Principal Dr. Amy Coyne. “I have thoroughly enjoyed being a part of their journey through high school and cannot wait to see what each of their futures hold.”

The class overall earned $10,051,216, topping by $1.6 million last year's school record of $8.4 million. To emphasize the increase, Dr. Coyne, Principal of Bay High, pointed out that in 2009, total scholarship numbers were under $1 million dollars.

Leading the graduates were the two top academic students - Bay High 2016 valedictorian Zachary Marlow, with a 105.17 GPA; and salutatorian Juliana Cook, with a 101.71 GPA.

Marlow is the son of Kari and Major Reese Marlow. At Bay High, he was active in the Air Force JROTC, Interact Club, Spanish Club, Bowling and National Honor Society, where he served as Vice President. He will attend the University of South Alabama in the fall with both a Presidential and Air Force ROTC scholarship. Marlow plans to major in math and pursue a military career. Marlow's estimated four-year awards totaled $459,500.

Cook is the daughter of Lisa and Thomas Cook. At Bay High, she was involved in National Honor Society, Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD), Spanish Club, Book Club and Fellowship of Christian Athletes. She is an active member of the Church of the Good Shepherd. Cook will attend Mississippi College, where she has received the Presidential Scholarship with Distinction and a Salutatorian scholarship. She will be pursuing an education major. Cook's estimated four-year awards totaled $389,700.

Mikayla Ott, daughter of Sharon and Michael Ott, is ranked third in the class and will attend Spring Hill College on academic scholarship to pursue a degree in studio art.

Iris Mann, daughter of Anne and Baxter Mann of Bay St. Louis, is ranked fourth in the class and will attend the University of Mississippi on a academic scholarship, studying foreign language and English as a double major.

Dr. Rebecca Ladner, Superintendent, stated “The accomplishments of the class of 2016 have left a mark on the Bay St. Louis -Waveland School District, and I wish the all the graduates a bright future.”

58 St. Stanislaus Grads Earn $6.6 Million+ In Scholarships

Members of the Saint Stanislaus Class of 2016 received awards for outstanding academic achievement during the school’s 2016 Senior Recognition Ceremony, held on May 22nd, in the Saint Stanislaus College Café. The annual event recognizes seniors who have merited special awards and achievements. Members of the Class of 2016 whose fathers, grandfathers, great great-grandfathers, and older brothers were also Saint Stanislaus graduates were recognized with Family Legacy Certificates.

Approximately 83% of this year’s senior class has thus far earned college scholarship totaling in excess of $6.6 million dollars. Seniors were accepted into 77 colleges and universities and they will use $1,916,306 of the awarded scholarships. Of the $1,916,306 being used, $1,215,317 of the accepted scholarships is merit based and $700,989 is athletic scholarships.

Saint Stanislaus is proud to recognize Mitchell Faust Walk as the Valedictorian of the Class of 2016 and Thomas Pasquale Reeder, Michael Joseph Sandoz, and Matthew Albert Saucier the 2016 Salutatorians. Mitchell, Thomas, Michael, and Matthew were formally recognized during commencement exercises on Saturday, May 28, at Our Lady of the Gulf Catholic Church in Bay St. Louis. Mitchell graduated with a 4.61 cumulative weighted grade point average and Thomas, Michael, and Matthew graduated with a 4.60 cumulative weighted grade point average.

Valedictorian

Mitchell Faust Walk

Mitchell, son of Mary Kay and Wesley Walk of Diamondhead, MS, was named a 2016 National Merit Finalist. He also earned the recognition as Saint Stanislaus’ 2016 STAR Student by achieving the highest ACT score, 36, of this year’s senior class.

Mitchell has achieved either Alpha or President’s Honor Roll every semester since the seventh grade. He is a member of the Brother Peter Basso Chapter of the National Honor Society, Mu Alpha Theta, Student Ministry Team, and is Vice-President of the Saint Stanislaus Student Council. Mitchell will attend the University of Texas.

Salutatorian

Thomas Pasquale Reeder

Thomas, son of Cindy and Patrick Reeder of Kiln, MS, has achieved either Alpha or President’s Honor Roll every semester since the seventh grade. He is a member of the Brother Peter Basso Chapter of the National Honor Society, Mu Alpha Theta, Student Ministry Team, Student Council, and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Thomas was a participant in the Hancock Youth Leadership Academy as both an 8th grader and a junior. He is a former retreat participant and retreat leader for the Saint Stanislaus Kairos retreat held at the St. Augustine Retreat Center. Thomas will attend the United States Naval Academy and play football for the Midshipmen.

Michael Joseph Sandoz

Michael, son of Mena and Rodney Sandoz of Long Beach, MS, has achieved President’s Honor Roll every semester since the seventh grade. He is a member of the Brother Peter Basso Chapter of the National Honor Society, Student Ministry Team, and was the Senior Class Representative of the Saint Stanislaus Student Council. Michael was also a member of the Saint Stanislaus SCUBA and Robotics clubs. He has twice made the Saint Stanislaus sponsored service trip to the Navajo Reservation in Klagetoh, Arizona. Michael will attend the University of Southern Mississippi.

Matthew Albert Saucier

Matthew, son of Georgia and Robert Saucier of Diamondhead, MS, has achieved either Alpha or President’s Honor Roll every semester since the seventh grade. He is a member of the Brother Peter Basso Chapter of the National Honor Society, Mu Alpha Theta, Student Ministry Team, Youth Legislature, and Fellowship of Christian Athletes. During the summer of 2015, Matthew was invited to participate in the first Student Assembly of the United States Province of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart held on the Saint Stanislaus campus. Matthew helped create the Saint Stanislaus Service Hour Team (SH0UT) his senior year. This group encouraged students to take on more service opportunities in the local area.

Matthew will attend the University of Mississippi.

Our Lady Academy Graduates Head For Higher Education

This year’s class of thirty-one graduating seniors has received offers of over $2.1 million in scholarships. The graduating class will be attending ten different universities. Class members are majoring in architecture, bioengineering, business, communications, education, pathology, science, and speech.

Valedictorian Quinn Cottone is the daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Joseph L. Cottone, Jr. of Pass Christian. Quinn is a member of Holy Family Parish. During her time at Our Lady Academy, Quinn has been a member of Junior National Honor Society, National Honor Society, OLA Ambassadors, National Spanish Honor Society, and Mu Alpha Theta. Quinn was named as the STAR (Student-Teacher-Achieving-Recognition) Student for the 2015-2016 school year. She was honored with the STAR recognition by achieving the highest ACT score in her class, a 31. Academically Quinn has earned Principal’s Honor Roll for all 8 semesters of her high school career. She has received recognition for Academic Achievement in Science, Math, History and English.

Quinn plans to attend Louisiana State University in the fall, where she received the Louisiana State University Academic Scholars Nonresident Award. She will major in Biological Engineering and plans to attend medical school. Quinn received the Principal’s Cup award during the graduation ceremony.

Diana Baroudi graduated with the distinction of Class Salutatorian. Diana is the daughter of Dr. Bassam Baroudi and Mrs. Kinana Baroudi of Gulfport. During her time at Our Lady Academy, Diana was an active member of several clubs and organizations, including the OLA basketball team, YMCA Junior Youth Legislature, OLA Student Council, OLA Ambassadors, and Students against Destructive Decisions. In addition, she has been a member of the National Honor Society, National Spanish Honor Society, and Mu Alpha Theta Mathematics Honor Society.

Diana will attend Auburn University in the fall, where she will major in biological science to pursue a career in medicine.

OLA's Ritten Tapped for Leadership Academy

| Laura Grace Ritten , a rising senior at Our Lady Academy, has been accepted into the Leadership Academy at Mercy College in New York. The week-long academy is held at the Westchester campus on the Hudson River and students visit the Manhattan campus near Times Square. Students learn leadership lessons from leaders at top global companies and participate in team-building activities. In addition, students visit Fortune 500 companies. Past visits include Goldman Sachs, Young & Rubicam, Bloomberg, PWC, and MTV, among others. Last year, over 1500 candidate applications were reviewed from over 20 states to select 150 students. Students are selected based on their GPA, and their demonstrated leadership and public speaking skills. |

Bay High Seniors Receive Time Capsule Packets from Elementary Teacher

Some of these students were under the guidance of the dynamic duo of Ms. Craft and her long-time assistant Elizabeth Cowles from kindergarten through 3rd grade.

The seniors were thrilled to receive the packets, as Craft had promised they would when they graduated. Emotions from laughter to tears flowed from the students as they unveiled their treasures. Artwork they had created, photos from classroom parties, letters they had written to themselves about their goals and dreams were discovered. There were even letters from parents, grandparents and other family members, some who have since passed away or are unable to express their pride and love due to illness or mental decline.

It's a tradition that Craft and Cowles began before Hurricane Katrina, taking care to preserve memories for their students. Safely stored in plastic tubs and left in the classroom, Craft says that she was relieved to find the packets had survived the storm. Despite the school being destroyed by flood and wind, Craft's classroom was one of the only ones that still had most of its contents remaining. “I cried as my family and I carried the boxes to my vehicle,” said Craft. “I knew that it was going to matter to someone. Since then I have become more and more persistent in collecting items for my students from family members. And since then I have also become much more protective of them. I now keep them at home.”

“I'd read an article very early in my teaching career about a teacher who'd done this and knew instantly that I was going to do the same for my students. I wanted my students to feel it all come full circle when they graduated by receiving the memory packets,” Craft added.

Fraiser Earns Scholarship from local Attorney Brehm Bell

The Brehm Bell Future Lawyers Scholarship is a $1000 one-time award. Fraiser will attend Millsaps University in the fall and is the daughter of Carole Sullivan and Jim Fraiser.

In her submitted essay, Fraiser said, “I want my life and career to be of advocacy, and as a lawyer I would be in a unique position to help individuals or groups of people who face social, economic, and political injustices. As a civil rights lawyer I would strive to gain a deeper understanding of systematic oppression and the way others experience the world differently than myself.”

A practicing attorney in downtown Bay St. Louis since 1995, Bell focuses his practice on personal injury cases and helping people who are overwhelmed or frustrated with the legal process. “Our legal system and insurance processes are hard for people to navigate sometimes,” said Bell. “We need bright, compassionate minds to enter the field of law to continue helping people have a voice. Miss Fraiser is that type of student and I'm glad to play a part in her future.”

Bay-Waveland School District to Provide Free Meals for Youth

All children in the community up to 18 years old will have access to free breakfast (8-9 AM) and lunch (11-12:30 PM) Monday-Friday. There's no fee or registration required and participants do not have to be residents of the area or students within the school district providing meals.

Bay-Waveland Middle School is located at 600 Pine Street in Bay St. Louis. For more information, please contact BWSD Office of Child Nutrition at 228-467-0405.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender. For a complete non-discrimination statement in multiple languages, please go to: http://www.fns.usda.gov/fns-nondiscrimination-statement

|

Rotary Teacher of the Month - April

Mrs. Audrey Mayer

Our Lady Academy Seventh, Tenth, and Eleventh Grade Religion Educational Background: Mount Carmel Academy, New Orleans (All Girls’ Catholic High School) and Loyola University, New Orleans, Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communications, Minor in History, and Diocese of Biloxi New Wine Catechist Certification (Three-Year program to certify as Parish/School Religious Coordination and Teacher) |

Honor Roll

|

|

Educational Shout-outs this month: Bay High Cheer earns second place in national competition, Bay St. Louis Rotary Teacher of the Month Dan Munger, BH senior tapped as semifinalist for prestigious national scholarship, HMS Junior Beta rolls at state convention, new basketball coach at St. Stanislaus, Bay High students place second in regional academic competition and K-registration for Hancock and St. Stanislaus video goes viral!

|

Honor Roll

|

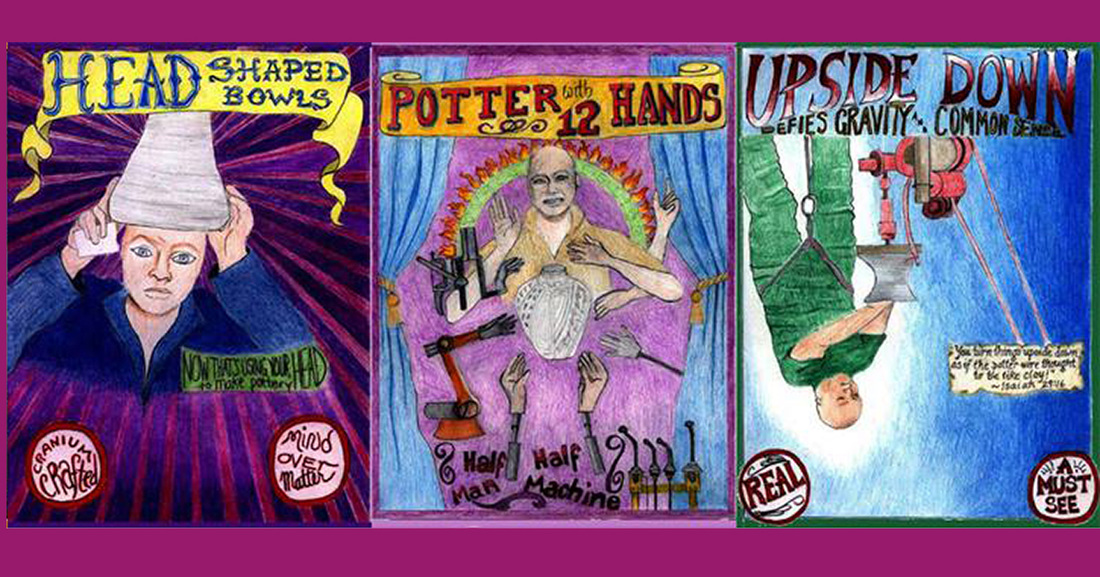

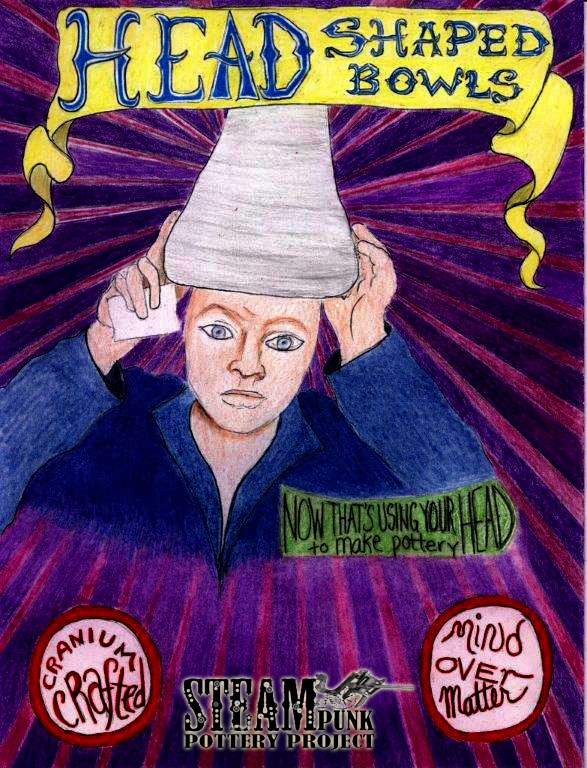

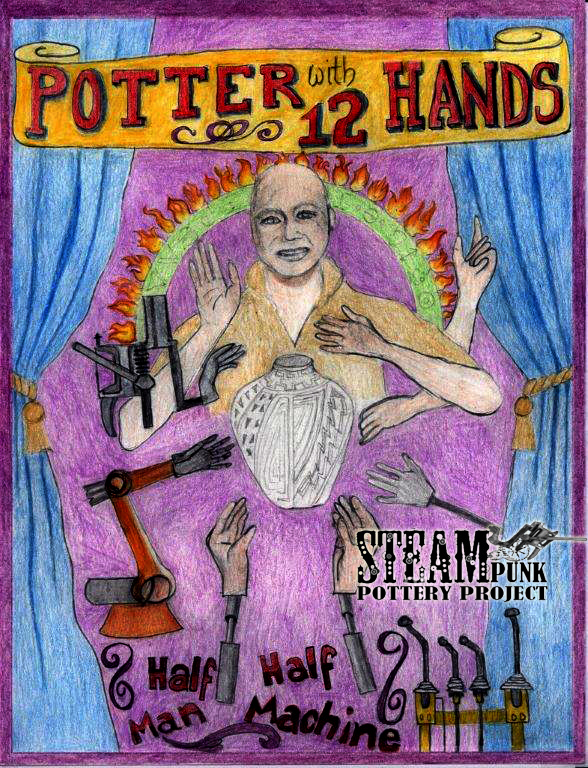

STEAMPunk Pottery Project

- story by Karen Fineran, photos by Robert Mosley

|

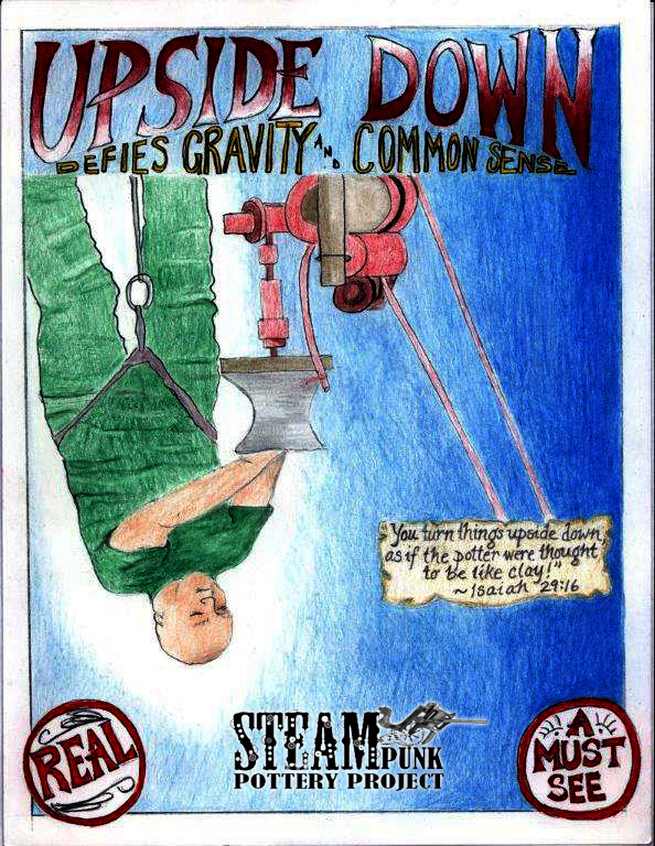

“You turn things upside down! Shall the potter be regarded as the clay, that the thing made should say of its maker, “He did not make me”; or the thing formed say of him who formed it, ‘He has no understanding’?”

— Biblical verse (Isaiah 29:16) written across a large sign on Barney’s extreme pottery-making contraption, “Agile Argile”

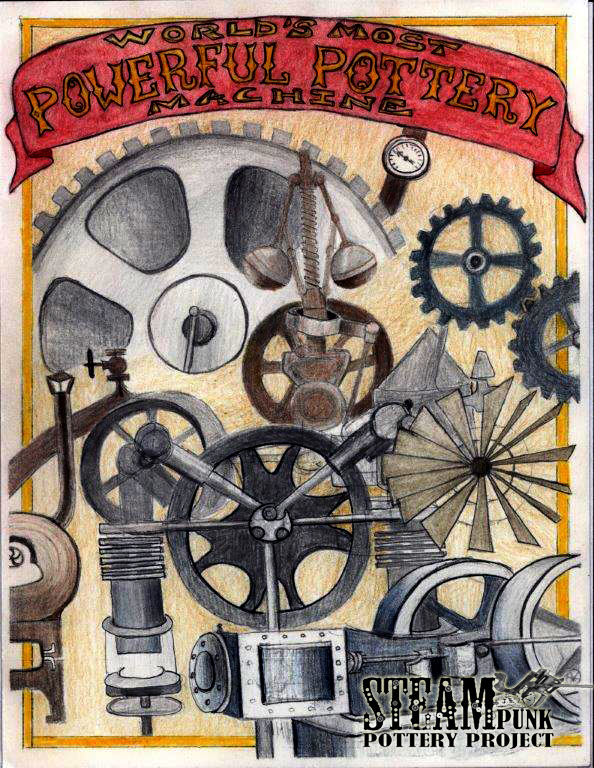

Whether at the helm of his bizarre-looking pottery machine, dangling upside down over an inverted pottery wheel, or forming clay pieces using his bare (and very bald) head, Steve Barney has taken pottery to a whole other level.

|

Arts Alive

|

The program is designed to integrate the STEAMPunk genre, the "Maker" culture and the experience of making pottery. The combination of elements will be applied to a unique new educational curriculum.

On January 30th, from 10am to 6pm on the grounds of the Ohr, Barney will perform a "sneak preview" of the project, informally demonstrating his radically innovative pottery-making machine and techniques.

Then on March 5th, Barney will be the host and the headliner at OOMA's kick-off event to introduce the new curriculum. It's scheduled to coincide with "Coast Com" (AKA Comic Com on the Gulf Coast) and the Mississippi Museums Association's annual meeting, being held this year at OOMA. The March event will feature George Ohr-like circus sideshow performances.

With an electrical engineering degree from Tufts and a lifelong interest in industrial design, Barney spent 15 years as an instructional design consultant in Boston and created interactive computer simulations for clients like museums and educators. But Barney had also been throwing clay pottery on the wheel since he was a child growing up in Buffalo, New York. Creating and teaching ceramic art were always an important part of his life, and he itched to bring his artistic interests and his passion for engineering together.

Barney initially visited New Orleans several times for Jazz Fests; when he made exploratory forays into the surrounding areas, he fell in love with the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Shortly after Hurricane Katrina, Barney bought and renovated several cottages in Old Town Bay St. Louis, throwing himself into the creative process of restoring historic homes. Within a couple of years Old Town became home.

Barney’s fascination with industrial machinery had taken a steampunk turn in the late 1990s. Steampunk as a movement incorporates a Victorian industrial aesthetic: think H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, or Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” with a modern sensibility.

While Barney had long felt influenced by the post-apocalyptic “Mad Max” movie series and William Gibson’s cyberpunk novels, his “eyes and mind were blown” when in 1997 he started attending the annual Burning Man art festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert. There he got carried away by the outrageously high tech/low tech contraptions, art cars, sculptures, and performance art on display and before long was exploring the diesel punk world of machine-design innovation and folk engineering, fashioning original contraptions out of old flywheels and belt pulleys.

Barney can use Agile Argile upside down, using reverse gravitational forces to throw an upside down pot by affixing a lump of clay upon its 19th-century cast-iron drill press, which then pulls itself down from its base by gravity.

Upside-down pottery throwing is not particularly novel, Barney explains. Many potters over the years have bolted wheels to the ceiling in their studios and “pulled down” surreally tall structures that are not possible to create on a standard potter’s wheel. Barney chose to further explore the process by inverting his body so his hand-and-body orientation to the wheel and spinning clay could be maintained while he was throwing.

Thus, Barney dons a climbing harness supported by an electric winch, working upside down with a remote control for as long as he can stand it before the dizzying rushing of blood to his brain impels him to re-right himself. When he first started climbing into the harness about 15 months ago, he could only hang for about 45 seconds before blackness oozed across his vision. Now he hangs for about 2 ½ minutes at a time.

Another striking visual feature of Agile Argile is a series of fixed and mounted mannequin hands attached to multi-axis pivoting arms to mimic the potter’s hands performing particular tasks. Functioning simultaneously, they conjure a demented Wizard of Oz or the multi-armed Hindu deity Shiva.

Barney's relationship with the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art began when he first visited OOMA a couple of years ago and learned about the fantastical works and vaudeville persona of the self-proclaimed “Mad Potter of Biloxi” George Ohr. Ohr was a master of carnivalesque self-promotion, and his pottery shop was an established coast tourist attraction where fascinated visitors could watch the Mad Potter give entertaining performances as they purchased mementos of their trip.

Ohr’s eccentric persona and flair resonated with Barney. “As I walked around the Ohr museum and grounds, I felt like I had come home," Barney said. Weeks after that visit, Barney dreamed of Ohr himself directing him to carry out Ohr's artistic vision using a steampunk premise. “This concept really belongs at the Ohr Museum,” Barney says. “It’s the right idea at the right place and the right time.”

Barney plans to take his machine to schools, museums, and festivals across the state and pique children’s interest in pottery, as well as inspire passion for learning about engineering, machinery, robotics, and other sciences.

“The steampunk concept really brought it all together for me. I thought, if I could teach pottery as a creative and cognitive process, and incorporate my passion for engineering, then I could gift to the children so many things that I’ve learned over the years. I feel like my ideas have the potential to touch thousands of kids nationwide.”

Barney sometimes appears in Bay St. Louis at Second Saturday and other local events, often in front of the Ugly Pirate bar. For more information about the SteamPunk Pottery Project, email Barney at [email protected].

Power Up and Sharpen Your Technology Skills

|

Bay-Waveland Habitat for Humanity has joined Hancock County Chamber of Commerce in its alliance with Pearl River Community College (PRCC) and Mississippi State University (MSU) Extension Service to provide area small businesses and homeowners with resources to improve their paths to success.

This fall, the Chamber worked in partnership with PRCC and MSU to hold technology workshops for small business owners in the PRCC Waveland Training Center. |

Talk of the Town

|

“Partnerships work,” said Tish Williams, executive director of the Hancock Chamber of Commerce. “When we work together to achieve community goals, we can make sure that our residents and businesses have the resources they need to connect, grow their customer base and enhance their skills.” Through these sessions, Williams says these partners want to empower people to achieve at their highest levels.

December’s workshops — which are free to attend — focus not only on technology like Excel basics and Microsoft PowerPoint, but include sessions on women’s empowerment, with speakers like Dorothy Wilson, publisher of Gulf Coast Woman magazine and co-founder of SUCCESS Women’s Conference. Upcoming workshop topics the group has considered for 2016 include a seminar on writing wills, and another on how to locate affordable homeowner’s insurance.

“We will find out what is important to homeowners and business owners and custom design these seminars to meet their needs,” said Williams.

For seminar registration, contact Brenda Wells at 601-403-1379 or [email protected]. To participate, you must know your email address, social media logins, Apple ID and passwords. Attendance is limited to the first 12 to register. Habitat for Humanity will provide computers to use during the session. You may register for one or all of the seminars offered. Seminars take place at the Bay-Waveland Habitat for Humanity / Hancock Chamber Training Center, 103 Central Avenue, Bay St. Louis.

For further business resources contact the Hancock County Chamber of Commerce at 228-467-9048 or [email protected].

December Habitat for Humanity / Hancock County Chamber Technology Seminars

9:00am-12:00noon: Excel 1 – Learn the basics of Excel, a spreadsheet program frequently used in today’s workplace or to keep track of your personal finances. John Giesemann, Mississippi State University Extension Service.

1:00pm-4:00pm: Microsoft Word – This session is designed to familiarize you with terminology, screen components and the most commonly used functions offered by Microsoft Word. Emphasis will be placed on proper document formatting techniques and file naming and file management. John Giesemann, Mississippi State University Extension Service.

4:30pm-5:30pm: Women Empowerment – Learn from some of the most successful business leaders in the region on how you can reach your potential to achieve your personal, financial and career goals. Presented by Angelyn Treutel Zeringue, South Group Gulf Coast Insurance and Chairman, Women’s Leadership Roundtable of the Hancock Chamber of Commerce.

Angelyn Treutel Zeringue, CPA, PWCAM, is a Trusted Choice independent insurance agent and President of SouthGroup Insurance Gulf Coast and AST Solutions, Inc. in Bay St. Louis. She has served on numerous community and corporate boards and has chaired the National Insurance - Agents Council for Technology. Treutel-Zeringue is a prolific public speaker on technology, insurance and business issues, includingn Internet Marketing, Workflow Efficiency, and Finance and Insurance. She has been honored as OneCoast Top Community Leader, Hancock County Citizen of the Year, National Top Women in Insurance, and America’s Elite Women in Insurance.

Dorothy Wilson

Dorothy Wilson

9 a.m. to 12 noon: Excel 2. It is not enough to know various features of Excel. A user needs to know how to use Excel productively. This includes knowing important keyboard shortcuts, mouse shortcuts, work-arounds, Excel customizations, and how to make everything look slick.

1-4 p.m.: Microsoft PowerPoint. Find out how to use this popular presentation software. It is one of the most useful, accessible, and popular ways to create and present visual aids to an audience.

4:30-5:30 p.m.: Women’s Empowerment. Some of the most successful business leaders in the region talk about how to reach your potential and achieve personal, financial, and career goals.

Leading this session will be Gulf Coast Woman magazine publisher and editor Dorothy Wilson. Gulf Coast Woman magazine, the voice of women on the Coast, aims to engage and inform South Mississippi’s women. Wilson also owns DWilson & Associates, a creative circle of editors, web designers, social media consultants, photographer and designers providing services to businesses and organizations.

9:00am-10:00am: Google Basics – What is Google and why do I need it? Andy Collins, Mississippi State University Extension Service.

10:30am-12:00noon: Facebook Basics – Join us to learn about the settings and insights on your Facebook Page. We will demonstrate different features to help you manage your Facebook page better. You must have access to a Facebook Page and have a minimum of 40 likes on the page you are accessing. Andy Collins, Mississippi State University Extension Service.

1:00pm-2:00pm: Internet & Social Media Safety to Protect Teenagers (for parents) - When it comes to online safety, social media has its own unique set of problems for teenagers. Find out how you can be involved in your teens’ use of social media. Find out how you can protect your children. Ryan Giles, AGJ Systems & Networks.

3:30pm-4:30pm: Avoid Banking Fraud - You will also learn how Cyber criminals compromise accounts and complete fraudulent transactions in many different ways through online banking fraud. Find out how you can protect your assets.

Hancock Education Makes the Honor Roll

|

Like the proud parents of an honor student on graduation day, supporters of quality education in Hancock County have a lot to feel good about. Our public and private school students, teachers and administrators are high achievers in not only academics but the arts and athletics as well.

Despite being underfunded by the state in recent years, local educators have worked wonders with what they had (and just imagine what they could have done with their fair shake of funding from the state!). Take a look at these well rounded accomplishments: |

Talk of the Town

|

Bay -Waveland School District

- Bay High School, which ranked 13th out of 249 high schools in Mississippi for statewide testing scores, has the highest graduation rate on the Mississippi Coast and the third highest rate in the state. And for the last three years, it's also had the lowest drop-out rates in the three coastal counties.

- The school won the Bronze Award among Best High Schools in America for four years, according to US News & World Report. The 2014 graduation class of 135 were awarded $5.5 million in scholarships. In 2015, 114 graduates pulled in an astonishing $8,374,566 in scholarship offers, setting a new record at the school and topping last year's record by nearly $3 million.

- Forty-five percent of students go on the attend two-year community college and 35 percent attend four-year universities.

- Scholarship carries over into athletics at Bay High, where all varsity team members have a 3.0 or higher grade point average. Recent honors include award winning efforts by the dance team, basketball and soccer teams, cheerleading squad and tennis team which keep crowding the school’s trophy cases.

Hancock School District

- The Hancock County School District’s testing scores ranked second out of 249 high schools and the high school was a top performer for three years in a row.

- Hancock’s graduation rate was in the top 5 for the Coast and the top 15 percent of all districts in the state. The 2015 graduates earned $6.1 million in scholarships. Among 2015 graduates, 48 received highest honors for 4.0 and greater grades; 36 students earned honors for 3.5-3.99 averages.

- More than half of the county’s high school grades enrolled in two-year community college and 36 percent opted for four-year universities.

- Outside the classroom, Hancock High students earned honors for band, dance, art, basketball, Junior ROTC, football, volleyball, fast pitch softball, bowling, golf, track, tennis, cross country and swimming.

St. Stanislaus and Our Lady Academy

- Accolades go to the county’s private schools as well. At the all-boys St. Stanislaus, approximately 90 percent of 2015 senior class earned college scholarships totaling more than $10.5 million. SSC seniors were accepted into 84 colleges and universities.

- Our Lady Academy is a parochial school, the only all-girls Catholic high school in the state. The class of 2015 had an average 25.7 ACT scores - higher than state and national averages. OLA’s 34 graduates in the class of 2015 earned more than $2,685,000 in scholarships, averaging $79,000 per graduate.

A Never-Failing Spring - Our Public Libraries

- story by Carole McKellar

|

“A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.” - Andrew Carnegie

Our public library lies at the heart of what makes Bay St. Louis a desirable place to call home. Studies find that people like to live near libraries and frequently decide to move to communities with strong public systems. Libraries are considered essential to the needs of an educated and literate population. Thankfully, we have an excellent library system in Hancock County. Public access to books has a long tradition, possibly dating from Roman scrolls made available to patrons of the baths. Circulating libraries were established in the 18th century, but they charged a subscription fee for their services. Private subscription libraries controlled membership and thrived as exclusive clubs. Peterborough, New Hampshire founded the world’s first tax-supported public library in 1833. Philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie provided money to start libraries throughout the United States. Carnegie built 1,689 free public libraries between 1883 and 1929. Eleven of those were built in Mississippi. The first Gulfport library was funded by Carnegie in 1916. The Carnegie Foundation also funded the libraries at Millsaps College and the University of Mississippi. My husband remembers going to the Carnegie Library in Clarksdale, Mississippi. That library, built in 1911, is still operating in the same building today. According to current government statistics, there are 9,207 public libraries in the United States serving 97% of the population. |

Bay Reads

|

During difficult economic times library budgets often decrease, though their role becomes more important. During recessions, libraries prove their worth to the community by offering job information, preparing resumes, and assisting online job applications.

There are many reasons why libraries matter. Let’s start with books. Most people can’t afford to buy or don’t have room for all the books they want to read. Our library has a large selection of books, DVDs, audio books, and e-books for loan. There are periodicals and reference books. If you are not sure where to find what you need, friendly, helpful staff members are readily available.

Computers are available to residents, and Internet access is free. Classes that improve digital literacy and use of online research tools are provided. The goal of the library is to provide lifelong learning for all members of the community by offering a wide range of programs for all ages.

All of our library branches have charming and engaging children’s sections that make early literacy a pleasurable experience. Story time is provided weekly at each branch for children from birth to age five. The programs include storytelling, crafts, and music.

The website, www.hancocklibraries.info/, is comprehensive. You can reserve books using their online catalog, or find the schedules for activities and events, such as Matinee in the Bay or the latest Authors & Characters event.

Meeting and conference rooms are available for community use. The rooms accommodate activities as varied as voting, movies, lectures, book sales, and a variety of classes.

“There is not such a cradle of democracy upon the earth as the Free Public Library, this republic of letters, where neither rank, office, nor wealth receives the slightest consideration.” - Andrew Carnegie

Read Me a Story

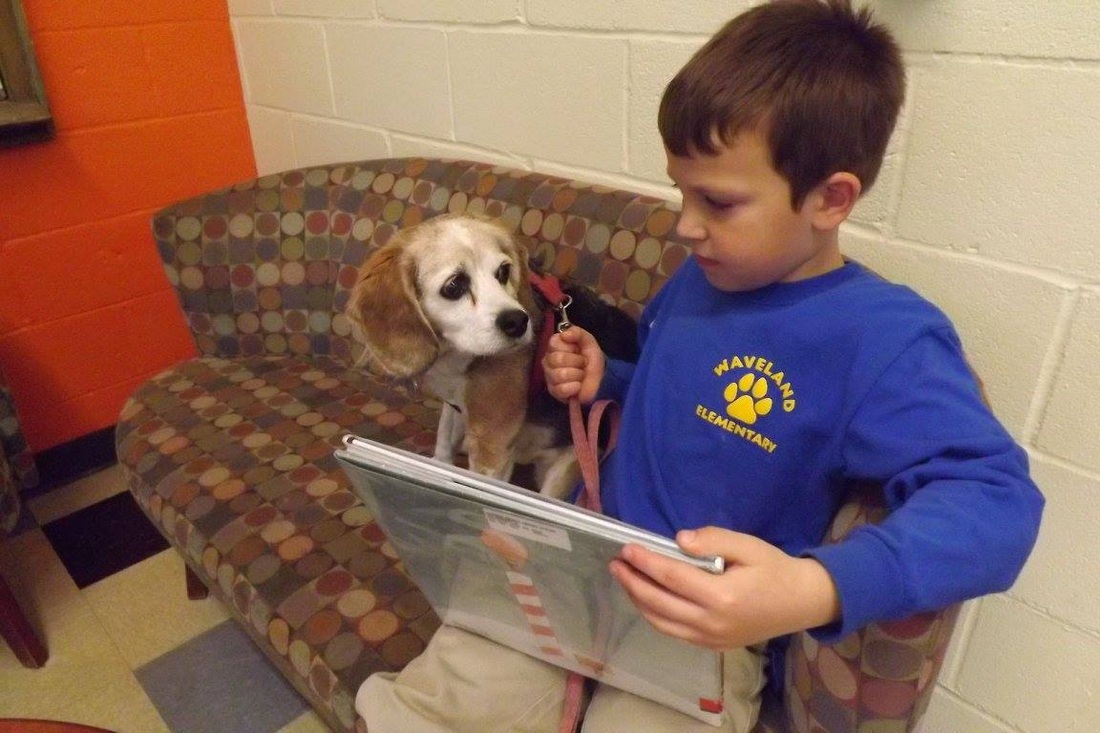

This month - Daisy Mae takes part in a reading program at the Boys and Girls Club.

|

I love being a service dog and a journalist. I get to do so many things and I am always so impressed that one good thing so often leads to another. Let me explain. During the Mississippi Week for the Animals two years ago I went to the Pearlington Library during story hour. I love meeting the children and a neat thing about going to the library or to the Boys and Girls Club is that I always get to hear a good story. This story hour was no exception.

We gathered around a short table with little chairs. I like the little tables and chairs because I can see better, otherwise all I see is knees and feet. So we settled in. The story selected was "Two Bobbies: A Story of Hurricane Katrina, Friendship, and Survival" by Kirby Larson and Mary Nethery and illustrated by Jean Cassels. |

Puppy Dog Tales

|

The wind and the rains came and there was no rescue in sight. Bobbi and Bob Cat had eaten all their food and drunk all the water that was left. After days Bobbi finally broke her chain and went in search of family, food and water. No luck. They were on the street for four months until they were rescued and taken to the Best Friends Animal Society shelter that has been set up in Celebration Station. That’s all of the story you get. To find out what happens you will have to get the book and ask your children to read it to you.

Micky Evans, founder of Friends and her beloved Catahoula, Isobel, went to schools and anywhere there were children to teach them how to be good stewards to their pets. One day while she was in her store (before the storm) a woman and her son came by and the boy recognized Micky and Isobel from a presentation she had given. When Micky asked him what he had learned he said, “spay and neuta your pets”. Kids are like sponges and they absorb as much as we can give them.

We started out reading at the library and then last year started at the Boys and Girls Club here in Hancock County as a joint project with the Hancock County Library. Club Director, Shannel Smith (Cleaver Good Neighbor, February 2015) was eager to help the students improve their reading skills and the parents were presented the idea at a parents meeting and like the idea. So what we do on the first and third Wednesdays is show up with dogs and we get read to. We educate a little but the real focus is to increase reading skills. It is so much fun for me to have the kids remember who I am and to be so eager to read to me.

Right now we have me and my brother Robbie and our beagle friend Rosie. We are adding another therapy dog for next time so that means we can read with 12 children at a time – 3 for each dog. The kids select a book and take turns reading aloud. If one stumbles on a word the others help out. What excites me the most is the improvement we see every time we come.

Start early with your children and have them read to you, their siblings and any pets in the home. If they don’t know the words – the picture can tell the story. Soon they will be getting books out and demanding that you listen to them read. Natalie pointed out one interesting point. When the kids come to read, they recognize us and we recognize them.

“They are getting affirmation,” Natalie told me. She said that they feel that “I am doing a good job – this dog is sitting next to me and listening." “When they start school and they don’t have a good foundation," Natalie said, “Studies show the kids cannot catch up.” Something that seems so simple as reading out loud is really quite profound.

So that is the program and what do I want you to do? Have your children read to you and their pets. You will find that time you spend together is calming, rewarding and so much fun. As an aside, if you don’t have children then you can read to your pets. We understand more than you think we do and we love to hear the sound of your voice. My person yaks at us all the time and we have awesome vocabularies. You can also read more about the benefits of reading programs by looking at the website, www.Librarydogs.com. There is an adorable Today Show presentation on their site about reading to dogs.

Finally, consider having your pet trained as a therapy animal. In the Sun Herald there is a notice that the Pass Christian Library is continuing their sponsorship for the Sit, Stay, R.E.A.D Visiting Pet Teams of South Mississippi Children’s Reading Program. A friend of mine, Eleanor Rose Hunter runs an organization called Angels on Paws out of Slidell, LA. Her group is an affiliate of Intermountain Therapy Animals R.E.A.D. program. Eleanor is working to set up a R.E.A.D, program at the Diamondhead library. If you are interested in more information about R.E.A.D. their website is www.therapyanimals.org.

Send my person an email for more information on the Friends of the Animal Shelter Reading with Friends or to get involved. She is at [email protected] or 228.222.7018

Keep your tail high and your feet dry – love Daisy Mae

- This month - A Dream Playhouse is the chosen class project of Leadership Hancock County 2015, but it's hardly child's play. Find out about the Leadership program and the 2015 class goal to raise awareness for CASA!

|

The class project may be a playhouse, but for the twenty-eight participants in the 2015 Leadership Hancock County program, it’s anything but child’s play.

The original playhouse drawing was selected by the Leadership class from dozens of entries submitted by by Hancock County school children. It’s being designed and built students at the Hancock County School District’s Career and Technical Center. When it’s finished, this Dream Playhouse will be raffled off to benefit CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocate), the local branch of an effective national program that works to protect the interests of abused and neglected children. |

Talk of the Town

|

click here to buy raffle tickets online!

click here to buy raffle tickets online!

Procrastinators will be able to purchase tickets at the last moment and the drawing will take place around 3:30pm. The family-friendly event will also feature cook-out food (courtesy of Tri-R Bar & Grill), free tours of the museum and music – as well as fun and games for children.

The Raising the Roof Patrons’ Party for the event’s sponsors will begin immediately afterward at 3:30pm, lasting until 5pm. In addition to the cook-out food, wine (donated by Rosetti’s Liquor Barrel) and beer (donated by Lazy Magnolia Brewery) will be served.

Raffle tickets are $5 each or five for $20 and can be purchased online here.

The purpose of the project is two-fold: the class hopes to raise both awareness and money for the CASA program, as well as showcase the Waveland Ground Zero Museum.

Since the program was introduced nearly two decades ago, thirteen classes have produced 320 graduates, many of whom have gone on to become “change agents for the good of Hancock County.”

For the past three years, Janell Nolan has served as the chair of the Chamber’s Steering Committee for Leadership Hancock County (LHC). She calls the program a community effort, saying that it wouldn’t be possible without the support of volunteers, sponsors and local businesses.

Nolan says that each September the new leadership class kicks off with a leadership assessment and an alumni meet and greet. That’s followed by a two-day retreat in October that focuses on team-building and leadership skills. That session sets the foundation for the next six months where the classes take a close look at the six building blocks integral to economic and community development in Hancock County: social infrastructure, workforce development, Stennis Space Center, economic development, civic infrastructure, and cultural heritage and preservation. The program also tasks each class with a project. LHC participants receive a certificate of graduation and celebrate their dedication and hard work in June, with a graduation ceremony and dinner.

“The personal and professional relationships that are built in the leadership classes are invaluable.”

Nolan has observed a few things about the program. “Every year, it is truly inspiring to see how the LHC participants – whether collectively or individually, digest the nine-month experience and immediately begin working on fulfilling a need or taking on challenges to improve the quality of life in Hancock County. The 2015 class came up with an innovative plan that would benefit both CASA and the Ground Zero Museum.”

“The LHC Class of 2015 has been working on this fantastic project,” says Nolan. “It’s been nothing short of amazing to watch them pull it together. They’ve involved the school districts, the children, the faculty and staff of the Career and Technology center and built partnerships with many local businesses.”

“In just a short period of time, they’ve already increased awareness of CASA’s mission exponentially. It’s a win-win for everybody – especially our future - the children of Hancock County.”

For more information on the Raising the Roof event, click here.

To read about CASA’s annual Mardi Gras Gala, click here for the January “Talk of the Town.”

This month, the Cleaver Good Neighbor is Shannel Smith, who is opening doors - and minds - for children in the community!

In a cozy, welcoming home on Third Street, live members of one of the oldest families in Bay St. Louis – and one of the oldest Creole families on the Coast. Myron Labat, Sr. and his wife Rhonda Labat greeted me warmly and told me a little bit about their family.

Myron, the former principal at North Bay Elementary School, has lived in Bay St. Louis his entire life. He attended St. Rose Elementary and St. Rose High School until it closed in 1968, graduating from Bay High. Rhonda is from Meridian, Mississippi, and met Myron while they were in school at USM Hattiesburg. Rhonda has worked at DuPont for 37 years as an Administrative Assistant in the medical department.

Categories

All

15 Minutes

Across The Bridge

Aloha Diamondhead

Amtrak

Antiques

Architecture

Art

Arts Alive

Arts Locale

At Home In The Bay

Bay Bride

Bay Business

Bay Reads

Bay St. Louis

Beach To Bayou

Beach-to-bayou

Beautiful Things

Benefit

Big Buzz

Boats

Body+Mind+Spirit

Books

BSL Council Updates

BSL P&Z

Business

Business Buzz

Casting My Net

Civics

Coast Cuisine

Coast Lines Column

Day Tripping

Design

Diamondhead

DIY

Editors Notes

Education

Environment

Events

Fashion

Food

Friends Of The Animal Shelter

Good Neighbor

Grape Minds

Growing Up Downtown

Harbor Highlights

Health

History

Honor Roll

House And Garden

Legends And Legacies

Local Focal

Lodging

Mardi Gras

Mind+Body+Spirit

Mother Of Pearl

Murphy's Musical Notes

Music

Nature

Nature Notes

New Orleans

News

Noteworthy Women

Old Town Merchants

On The Shoofly

Parenting

Partner Spotlight

Pass Christian

Public Safety

Puppy-dog-tales

Rheta-grimsley-johnson

Science

Second Saturday

Shared History

Shared-history

Shelter-stars

Shoofly

Shore Thing Fishing Report

Sponsor Spotlight

Station-house-bsl

Talk Of The Town

The Eyes Have It

Tourism

Town Green

Town-green

Travel

Tying-the-knot

Video

Vintage-vignette

Vintage-vignette

Waveland

Weddings

Wellness

Window-shopping

Wines-and-dining

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

June 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

August 2014

January 2014

November 2013

August 2013

June 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

October 2012

September 2012

May 2012

March 2012

February 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

July 2011

June 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed