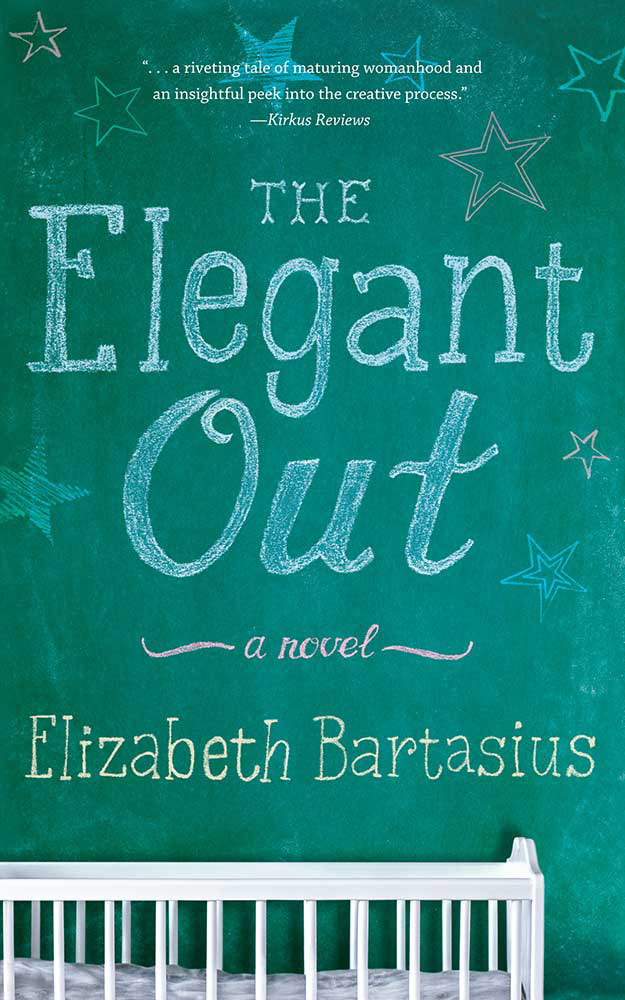

An author acknowledges how a small town, its people and a storm freed her to create her first novel.

- story by Elizabeth Bartasius

Before I landed in Mississippi, I felt like debris whipped around in the emotional hurricanes of anxiety, “shoulds,” and expectations. When I moved to the Bay in 2003, my first marriage disintegrated; life was in chaos. Then Katrina (the literal hurricane) hit.

All seemed lost, yet all around me I discovered a different way to approach life. People cared for each other, despite differences. They laughed over meals served by volunteers in tents. The Coast’s collective rallying cry — we will rebuild; and it will be bigger and better! — bolstered me. I learned that if I wanted something done, I was the one to step up and do it. Close-knit Bay Saint Louis offered each person the space and opportunity to share their unique gifts, to be heard, and, then to rise. In the Bay, I found an underlying current of support and a celebration of my own voice. I also stopped being in such a hurry. The beat of small-town life became my metronome. I paced myself accordingly with morning strolls to the ‘Bird for a take-out cup of tea, then to the long stretch of white beach. At the town’s shoofly deck, I took a moment under the oak to admire the dripping Spanish moss. In the slowness I began to appreciate the moment, to listen, to look, to observe all that was around me, all the while discovering who I was inside. Away from the frenzy of urban life, Bay Saint Louis gave me pause to think and the energetic space to write. And, there is much to write about! With drama, grit, beauty, character, and color around every corner; Bay Saint Louis offers so much sugar for a writer looking for ideas. Rumbles of a train. Sticky hands after crawfish. Long, lazy porches for impromptu hellos. Morning dew and sweat falling from trees like the drizzle of rain. Crab Fest, Pirate Fest, Bridge Fest, Second Saturday. Heat rising from an August midnight. The yellow light of the 100 Men Hall on a foggy night. Candied bacon from the Sycamore House. And, of course the whirring of an espresso maker as Laura or Whitney, still ten years later, greet you from behind the counter of the Mockingbird. (While not one single scene in "The Elegant Out" was set at this iconic establishment, many first drafts were written here.) All the bits and pieces I picked up around town began to inform the novel, from the blue house on Carroll Avenue to the carpool line at North Bay Elementary to Hairworks, where vines choked the outside A/C unit and sparked an idea for the protagonist in "The Elegant Out." Want I wanted to achieve didn’t seem so impossible wrapped in the down comforter of Bay Saint Louis. Over the years, our life in the Bay became a beautiful rut. I had resisted that dependable structure for so long; thinking I was only interesting, or likeable if I was moving and shaking. In the end, the laid-back, daily rhythm of this charming coastal town became my salvation and my transformation. When I stopped to acknowledge how much that rut stabilized and sourced me, the words unraveled; I rushed home to write them.

Please join Elizabeth Bartasius for a book signing and reading on Wednesday, May 15 at 5:30 pm:

Smith and Lens Gallery 106 South 2nd Street Bay St. Louis

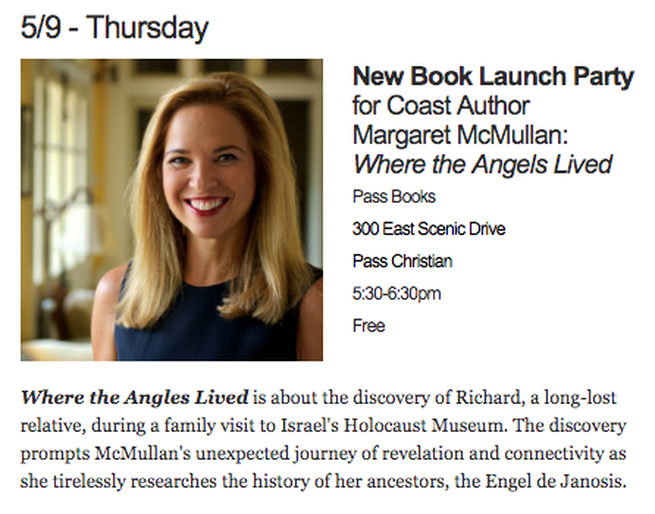

In the writer's open letter to the author of this compelling book, he explains why he cannot review it.

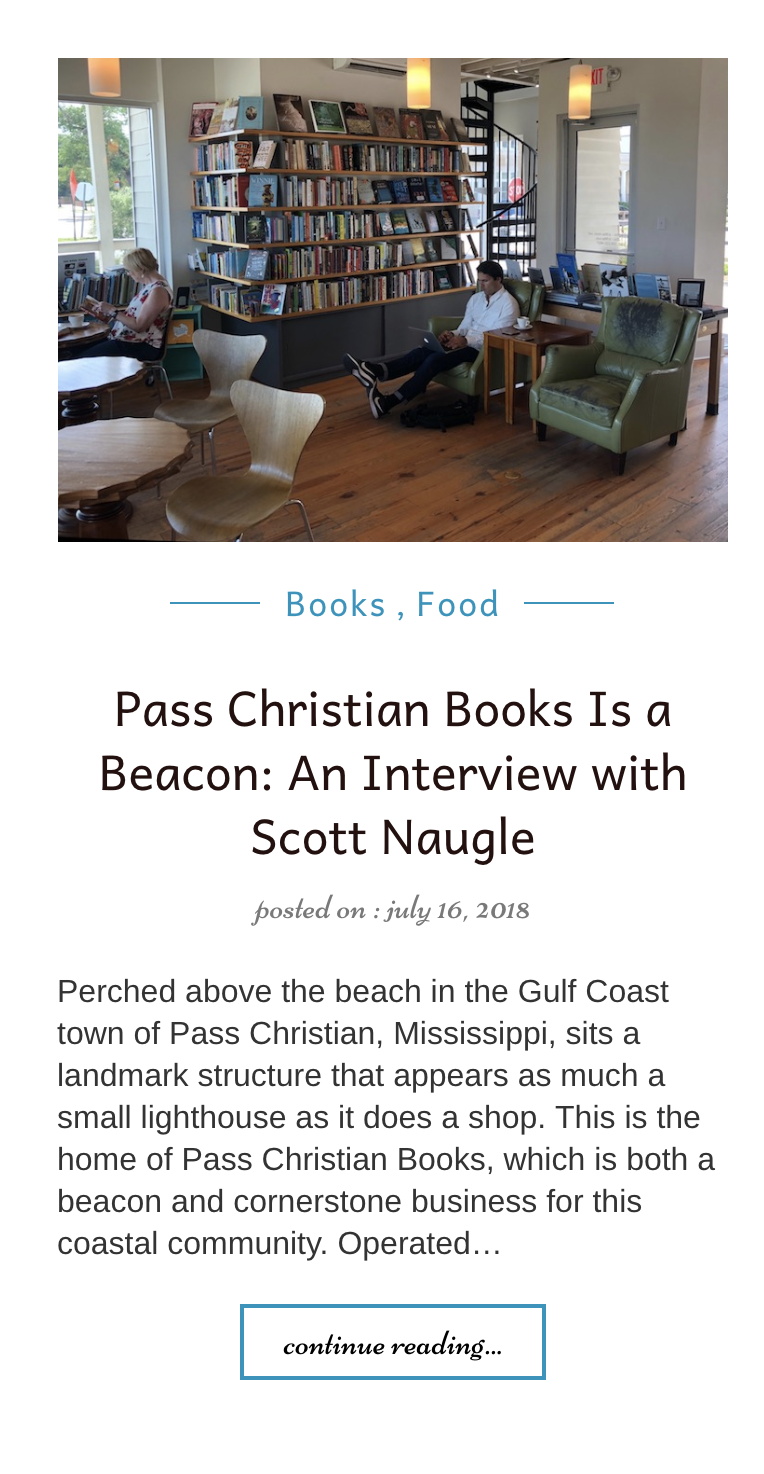

- story by Scott Naugle, photos by Patrick O'Connor

Dearest Margaret,

It was almost fifteen years ago that I first reviewed and wrote about one of your books, “How I Found the Strong,” for a literary magazine. Your family’s history, on your father’s side, was the impetus for the young adult novel. While we were friends at the time, we’ve become closer. I consider your family an extended family – your mother Madeleine, husband Pat, and your son James, whom I still can’t believe the years have passed so quickly that he is graduating from college next weekend. You’ve hung up on me during phone conversations and slapped a cellphone out of my hand when I was texting and driving (you were right to do this, even underscoring it with adult language). For these reasons, I struggled with whether I would have the professional distance to review and discuss “Where the Angels Lived”. How could I pass judgement on the intensely personal and compelling work of a close friend? Transparency is always the correct approach, so if I am asked to review your most recent work, I’ll be transparent about our long friendship. I wanted you to know this. Your love for your family, past and present, and their histories appear to be a consistent motivation for your intellectual work. “How I Found the Strong” was inspired by a long-lost manuscript, “The Life and Times of Frank Russell.” Frank Russell was the great-uncle of your grandmother on the McMullan side and dictated his remembrances of life in Smith County, Mississippi. As you recollected in the novel’s afterword, “the part of Frank’s story that interested me the most, however, was what he did not talk about.” A historical detective, you used the facts at hand and created the story of the young fictionalized Frank Russell into an award-winning novel. A few years later, in 2008, you visited the Holocaust Museum and learned of a relative you had never heard of – “Richárd.” The museum archivist looked at you and declared, “Look at me, you are the first to ask about him. Do you understand? No one has ever asked about this man, your relative, Richárd. No one ever printed out his name. You are responsible now. You must remember him in order to honor him.” As the curious and impassioned intellectual I know you to be, you had no choice but to learn more about Richárd Engel de Jánosi. Like the nonfiction manuscript of Frank Russell that you spun into a beautiful novel, you were presented again with a previously unknown, and hidden, piece of your family’s history. The story of Richárd Engel de Jánosi is so incredible, though, that a nonfiction exhumation of your family’s story through research is the appropriate platform. Life is stranger, and far more brutal, than fiction. But against what may be the safe or prudent thing to do, in a Hungary that remains deeply anti-Semitic, you traveled to ask questions about a Jewish uncle that you never knew existed nor was ever acknowledged in any way. You met resistance, both official and subtle. As I turned the pages of the advance copy of “Where the Angels Lived” that you were kind enough to give me a few months ago, I feared for your safety. As you recollect in “Where the Angels Lived”, “Never heard of him,” your mother snaps when you ask about Richard. “You must have it wrong. I don’t have time for this.” Madeleine McMullan hangs up.

Richárd was the son of your great-grandfather, Adolf, as your research in Hungary revealed. Adolf created a vast business empire of land-holdings, lumber, and coal by his mid-thirties. He started without a penny and succeeded despite the anti-Jewish legislation in Hungary. He had to pay “tolerance taxes.” You speculate, “Maybe he was granted immunity as a Jew because he took such good care of his mostly Catholic workers. He built them homes, schools, bathhouses, and churches. He paid for their teachers and priests.”

All of this began to fall apart in the years leading up to 1944. And while many members of the Engel de Jánosi family sent their money to Swiss bank accounts, converted to Catholicism, changed their names, or took the opportunity to leave the country early, Richárd, strong and quietly defiant, resisted. One of the most beautiful passages in your book is when you use your considerable talents as a novelist to bring Richárd to life for us from the few facts about him: “He looks to be the kind of relative I would have loved – tall, distant, cool. The quiet type, pensive and precise. I would have tried to make him laugh… He looks so sure of himself, even a little defiant, stubborn. Maybe too proud. Maybe he believed too much in his own decency, maybe that’s what got him killed.” What you later learn is that your mother, at the age of ten in April 1939, was spirited from Hofzeile, the family estate, at night with her mother, your grandmother, Carlette. “My mother wore a dark blue coat several sizes too big so that she could grow in to it. My mother had the red measles, which had spread into her eyes. [My grandmother] told my mother not to look back, to never look back.”

Later, as the train was stopped at the border crossing, “the German fear of germs” prevented the officers who boarded the train from entering the cabin where your mother suffered. “Carlette slid the papers under the door… They kept their gloves on… held the documents at the corners” and quickly stamped them.

Learning all of this was too much for you. Against your grandmother’s advice to your mother eighty years ago, you had looked back. “Sitting there in the pew carved of Moravian oak, I start to shake. I curse every last Hungarian who deported or murdered my family. See, Look at me. My mother got out and she had me and I had a son. You didn’t end us.” Richárd, as you learned, stayed and administered the family businesses until he was met at his front door “by a black car with swastikas on the doors.” He was loaded onto a cattle car and taken to the concentration camp in Mauthausen. Your mother never discussed the Hungarian side of the family, instead selectively acknowledging the French lineage of her mother’s side. You found and communicated with the only other living member of the Engel de Jánosi family of your mother’s generation, Anna Stein. Recovering from your father’s death and healing from a new hip, your mother was willing to return to Europe in 2013. As your mother and Anna meet, you reflect that “Keeping secrets kept them alive, but that’s also how they lost contact with their families… They both know how to suffer and they both know how to worry… It’s the living they sometimes have trouble with.” After the visit with Anna Stein, you boarded a bus with your mother and she begins to cry, “Her weeping becomes guttural, the same sound she made the day my father died. Her slight shoulders shake and she puts her head into the crook of my arm. She is crying for everything and everyone – her dead husband, her father, her mother, her lost family and country. She is crying for herself and for all those in her family she knew and never knew.” And this Margaret, my dear friend, is what I have to tell you in this long letter – I won’t be able to review “Where the Angels Lived” if asked. It’s too close. It’s emotional – and yet, in the end filled with hope and love and leaves me with a sense of a future for humanity because of what you did. I cannot add words or commentary to something so beautifully lived and written. With much love, -Scott

“Where the Angels Lived: One Family’s Story of Exile, Loss, and Return”

By Margaret McMullan Calypso Editions ISBN: 9781944593087 $19.95

Books may be ordered (and shipped, if requested) here.

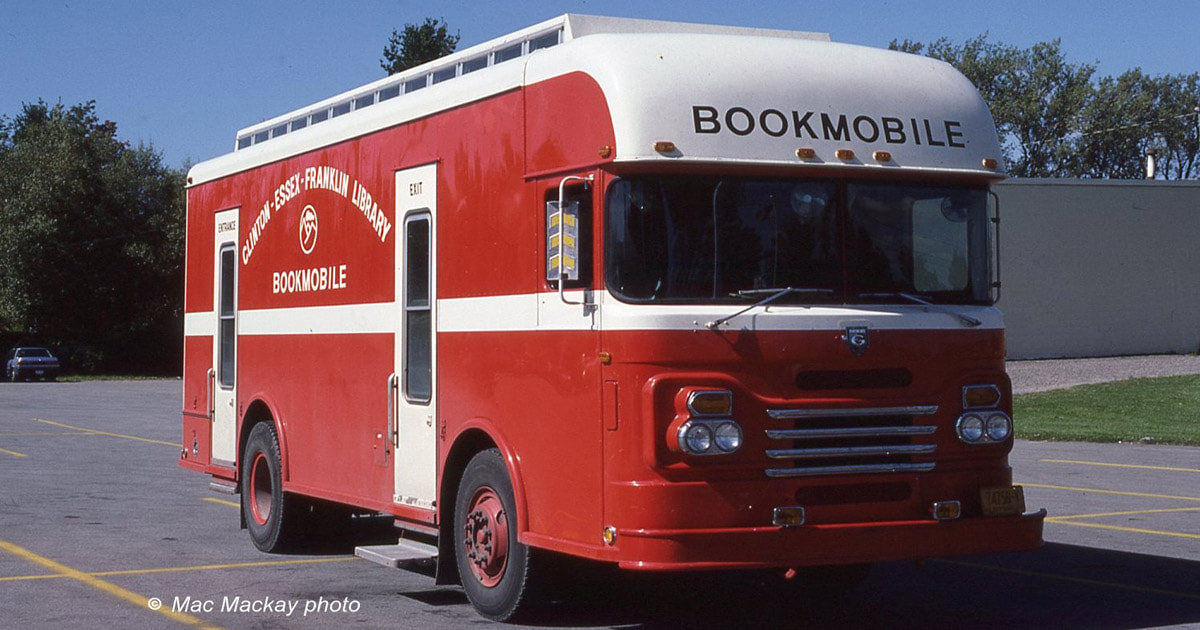

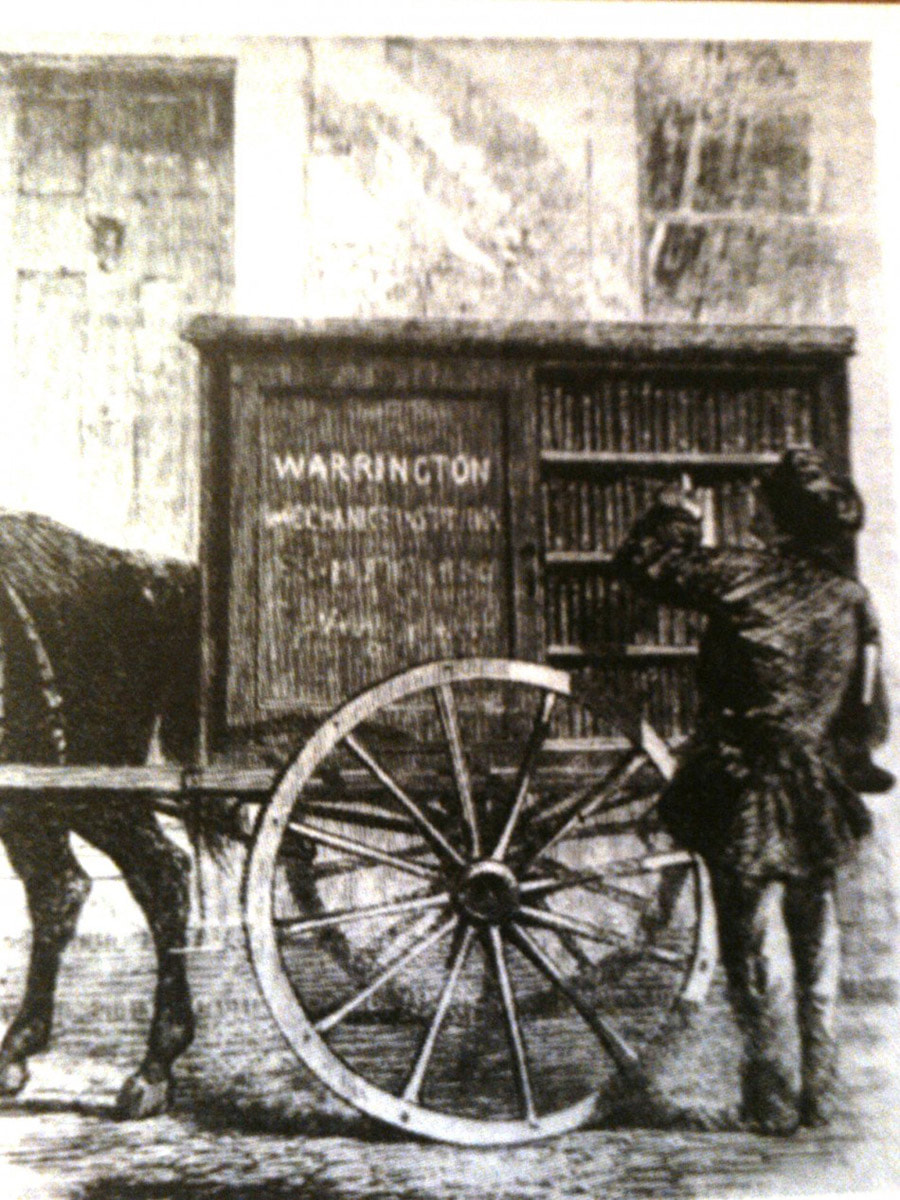

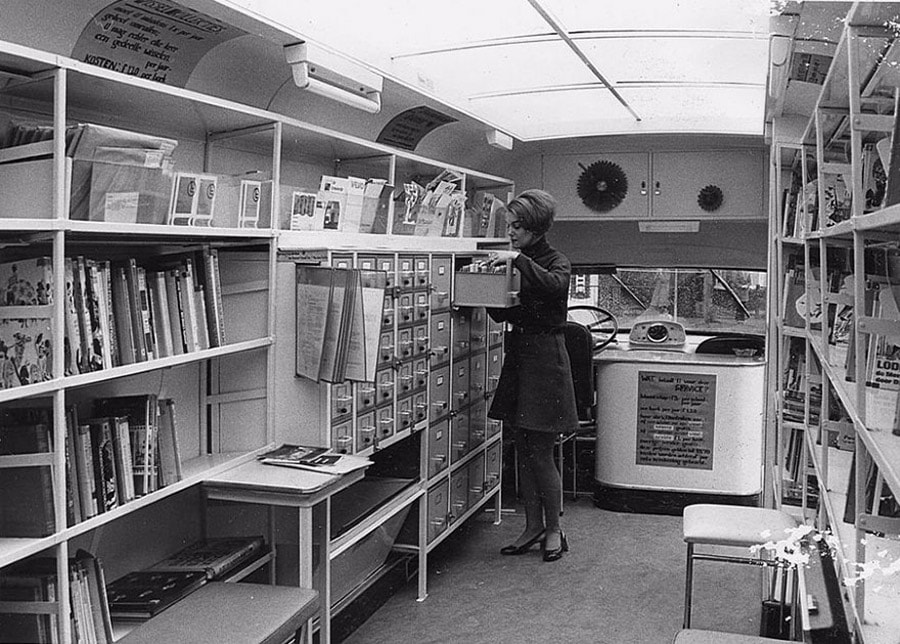

These four wheels transported books to readers - and readers to untold adventures.

- story by Scott Naugle

Davidsville remains a small community in western Pennsylvania. It was founded in the 1830s, German stock, dairy farmers, and a dry town, not by law, but because it was considered prudent to avoid spirits. The Lutheran church at the top of the hill at the eastern bend on Main Street recently celebrated its dodransbicentennial (175 years). My relatives from the early eighteenth century are buried in its cemetery.

Main Street, logically, is the main thoroughfare. In the winter after a heavy snowfall, it had just the right slope to serve as our sled-riding racetrack. After it was plowed, scraped clean and salted, we moved to the cemetery to ride our sleds in the deeper and fluffier snow. Too young to know it then, but this was only the first in a lifetime of blasphemous acts on my part. A bookmobile is a vehicle, often a truck, and nowadays possibly a tractor trailer, designed for use as a library. Books are transported to readers, often in rural or underserved areas, encouraging reading, engagement with ideas, and literacy. The first bookmobile, or horse-drawn book cart, dates to 1839. It was a frontier traveling library in the western United States, established by the publishing house of Harper & Brothers, known in the present day as HarperCollins, one of the world’s largest publishers. Like so many childhood memories recalled through a hagiographic lens, I assumed that the Somerset County Bookmobile was a thing of the distant past. Fortunately, I checked. The big red creaky behemoth, dually tires on the rear, has been replaced with a long bright heavy-duty truck, green, blue, and bright, with large lettering shouting BOOKMOBILE. Literature still rolls among the Appalachian Mountains of Southwestern Pennsylvania. Among the many pleasant memories of childhood, those connected to reading and books are most vivid. I easily recall the two steps up through the tall bi-fold doors into the bookmobile as big ones for a young lanky boy. Once inside, it was a paper cocoon of hardback books, shelved spines out, with the identifying Dewey Decimal number easily visible taped on the lower outside edge. There was order in this little bus, comfort, tidiness, with a small card catalog as a guide. All questions and conversations were whispered to the librarian/truck driver. She had a small desk attached to an interior half-wall behind the driver’s seat. I’ll call her Mrs. Blough, because that was likely her name if it wasn’t Mrs. Kautz. No more than four books were to be checked out for two weeks. As a matter of pride, I imagined, Mrs. Blough always had her date stamp prepared to two weeks in the future and a moist ink pad at the ready. She precisely stamped the due date on the glued card in the back of the book and underscored it by chiming, “this book is due back on August 4th, 1968. There are fines if it is late.” Over the summers I read through Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, The Hardy Boy Mysteries, and the crime-solving of Encyclopedia Brown. By my preteen years, I discovered Thomas Paine and The Age of Reason, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus from this faded red bookmobile. Bram Stoker’s Dracula could only be properly read late on a hot summer night. Stoker’s writing style oozes succulent prose deepening the darkness of midnight reading under a small bedside lamp while building suspense, horror, and trepidation for the appearance of the dark, flowing cape of the titular, fanged vampire. Four books a week was a tad light for me even at nine years old. I was able to read eight a week once I convinced Mrs. Blough that I was also checking out books for my mother. To legitimize the additional four books, I wrote them on a notecard before entering the bookmobile. I pulled out the list after obtaining the first four books I wanted and then pretended the books listed on the notecard were for my mother. Honestly, I never felt that I was fooling Mrs. Blough. My mother was unknowingly the best-read adult in Davidsville. Serendipitously, the bookmobile always parked in front of Main Street Bakery. A stack of books, chocolate milk, and a warm cinnamon-sprinkled donut and I was content. Would life ever be better than this? When the scheduled two hours had passed, Mrs. Blough would secure the rear and side doors, then climb behind the large steering wheel. Sitting stiffly upright, hair tightly pulled up into a peppery gray bun, she would depress the clutch and crank the engine. While grinding the engine into first gear, Mrs. Blough, librarian and truck driver, steered our bookmobile onto Main, popping the clutch as she headed north over curvy, hilly roads to the afternoon stop in Stoystown.

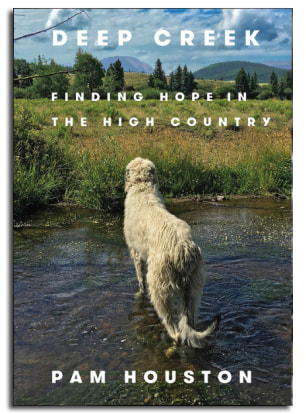

Cradled in the Colorado Rockies with a menagerie of animals, author Pam Houston comes to terms with her past and finds strength in her surroundings.

- story by Scott Naugle

Author Pam Houston will sign books and speak about her new memoir, Deep Creek, at Pass Books, 300 E. Scenic Drive, Pass Christian, on Thursday, Feb. 21, 6pm - 7pm. Click here for more details.

Houston recounts and contextualizes her struggles from a childhood of physical and mental abuse by both parents forward through decades of introspection, eventually locating a measure of peace and happiness in the present day. She sourced both therapy and solace from a large ranch in Northern Colorado, high in the Rocky Mountains, near the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

Many know Houston from the best-selling Cowboys Are My Weakness, her work as a columnist for Outdoor magazine, or the collections of short stories. She is currently the Director of Creative Writing at University of California, Davis and travels the world mentoring at writer’s workshops. Houston unearthed her uphill, rocky footpath to a mountainside respite after years of agonized wandering, “… and so my mother died, drunk and unhappy, and I found my way to this ranch, where I protect and am protected by animals, this place where nature controls how I spend my days and how I spend my life, this place where I can love every season.” The four-legged menagerie loved by Houston includes Icelandic sheep, dogs, mini-donks, horses, cats, and a short visit by an orphaned baby elk. Within all the moments of pure joy the animals inspire, there are also notes of sorrow. “In 2014 I lost Fenton Johnson the wolfhound,” she recounts. Houston was out of town leading a writer’s workshop when she received word of Fenton’s failing health. She returned home immediately by air, landing in a Denver snowstorm. “The weekend was everything all at once. It rained and snowed and blew and eventually howled, and I slept out on the dog porch with Fenton anyway, nose to nose with him for his last three nights.” The story of Fenton was an emotional one for me, striking close to home. I recently lost Snopes, a feisty, gnarling, grumbling, old, five-pound poodle, an ever present companion in charge of the house for the past ten years. When I received the call that Snopes was dying, I stood helplessly in chilly air on a concrete sidewalk corner outside of the office at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. I am consoled by the fact that he died in the arms of the only other person who loved him as much as I did. It was a Sunday mid-morning in Pass Christian several months ago and Pam Houston sat down beside me in a green upholstered armchair. She held her coffee in a white porcelain cup, silently, absorbing, watching the sunlight sparkling and bouncing off the undulating Gulf water. The previous evening, a whisper before midnight, I listened in awe as Pam stood in a parlor just up the street on Scenic Drive, ten or so others sprinkled around the room, reciting a long poem, one that she explained had moved her. I’ve forgotten the poem, but the passionate recitation mesmerized me. I was taken by someone so soulfully enthralled with emotion and ideas as conveyed through poetry. Now, she leaned toward me in the light-washed room and asked what I thought of Hunger. “It is one of my favorite novels,” I blurted. “Several years ago I read through all of Knut Hamsun’s work.” My response, judging by the expression on her face, initially appeared to puzzle her and then slowly changed to one of slightly bemused understanding. What kind of a person responds with an obscure Norwegian novelist’s work, a Nazi-sympathizer from the last century, when at that moment Roxane Gays’ Hunger: A Memoir of Body was at the top of the bestseller list? Houston gently corrected me. “In spite of the encroaching darkness, there’s nothing out here to be afraid of,” Houston recalls in Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country before a late day walk on her property. “Coyotes are not brave enough to attack a full grown woman and a 150-pound dog, even a whole pack of them. Mountain lions hunt at dusk and dawn, but in this country, there’s never been an attack on a human. A black bear won’t be hanging around on the riverbank, but even if he were, he’d hear us before we’d hear him and hightail it back into the forest.” There’s not much of anything, two-legged or four-legged, that Houston is afraid of any longer. Houston’s depth of insight and barebones honesty, her fluency and descriptive agility with the written word, brings Virginia Woolf to mind, ruminating in A Room of One’s Own: “The whole of the mind must lie wide open if we are to get the sense that the writer is communicating [her] experience with perfect fullness. The writer, once this experience is over, must lie back and let [her] mind celebrate its nuptials in darkness.”

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country is a memoir of strength, resilience, and love. It’s an affirmation of life, a “nuptial” unifying beauty with honesty, a Rocky Mountain transcript of Woolf’s ideal. I hope that Pam Houston permits herself a moment of celebration.

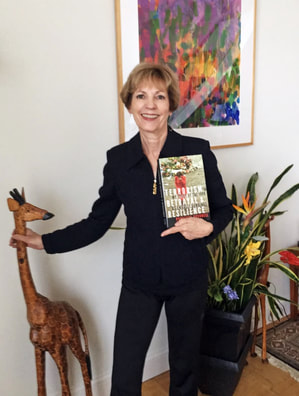

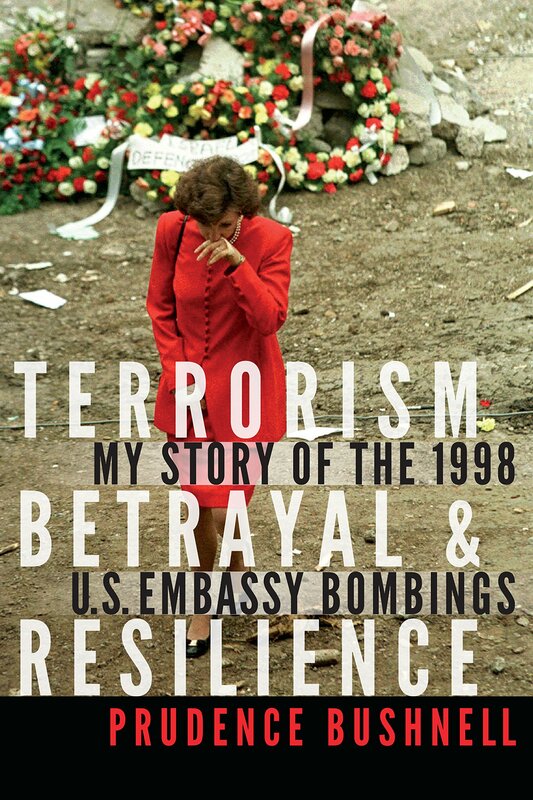

Former U.S. Ambassador and survivor of the 1998 embassy bombing in Kenya, Prudence Bushnell, tells that story in her gripping new book, "Terrorism, Betrayal and Resilience." With the emphasis on resilience.

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

Pru Bushnell will be speaking and signing her book at Pass Books (300 E. Scenic Drive, Pass Christian) from 5:30pm till 6:30pm, on Tuesday, January 29.

At noon on January 31 she will speak to a joint meeting of Gulfport’s Kiwanis and Rotary clubs.

In 1998, Pru was American ambassador to Kenya when the embassy in Nairobi was bombed by the radical Islamist group al-Qaeda – back before most of us had heard of al-Qaeda.

She did not die. Pru lived to tell her firsthand story of the bombing, its 213 fatalities and 5,000 casualties. A story that never inspired congressional hearings and is largely forgotten except by those who were there.

And in telling that story from a hard-hitting, non-partisan perspective, she illuminates flawed characters, policies and agencies. For it isn’t always a flattering portrayal of the national security community or politicians. Her exchanges with Susan Rice, Madeleine Albright, Bill Clinton and other “name” public servants sometimes make you wince. This is a minefield of what-ifs. Pru grew up in exotic places and largely patriarchal cultures, everywhere from Paris to Pakistan. Her father was in the foreign service, her mother the perfect foreign service wife, not an easy job that included, in post-war Germany, hosting orphans and helping widows.

But the men were in charge.

“As a girl growing up in the 1950s, it was inconceivable that I could become a leader, much less one who excelled in disasters,” Pru writes. “My only role model was Joan of Arc, and I was well aware of what happened to her when she put on a pair of pants and led men.” So it surprises no one more than Pru what a continuous adventure her life has been, a serial of true and turbulent stories that make a mockery of Hollywood and its “Homeland”-style heroines. From her first assignment in Dakar, Senegal, she has worn the pants and embraced the leadership role fate assigned her.

Before the embassy bombing in Kenya, Pru worked in Washington in the State Department’s Africa Bureau during the Rwandan genocide that slaughtered 800,000 people. “We were doing nothing to stop the killing, so I took it upon myself to call Rwandan military figures perpetrating the genocide to let them know we were watching and to advise that they would be held personally accountable for their deeds,” she writes. That episode of her life would be depicted in a movie, “Sometimes in April,” in which Pru is played by actress Debra Winger. The cover of her new book – Pru is walking away after laying a wreath at the bomb site in Nairobi – is a photograph by John McConnico that won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Photojournalism. From Kenya, still suffering with post traumatic stress, Pru became ambassador to Guatemala, hardly a healing place. There she was burned in effigy and watched, from a distance, as the United States was attacked by al-Qadea on September 11, 2001.

Now retired, in theory only, she crisscrosses the country giving talks about leadership, mostly to women. She lives in Washington with her husband, Richard Buckley, in a home with a view across the Potomac of the Lincoln Memorial.

This visit to the Pass is due to her friendship with former State Department employee and Pass resident Betty Sparkman. The book, published late last year by Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, is on sale now at Pass Books.

One of the longest-running syndicated columnists in the country and author of eight books, award-winning writer Rheta Grimsley Johnson divides her time between Pass Christian and Iuka, Mississippi. You'll find her books at Pass Books and other book retailers. Read more about herhere.

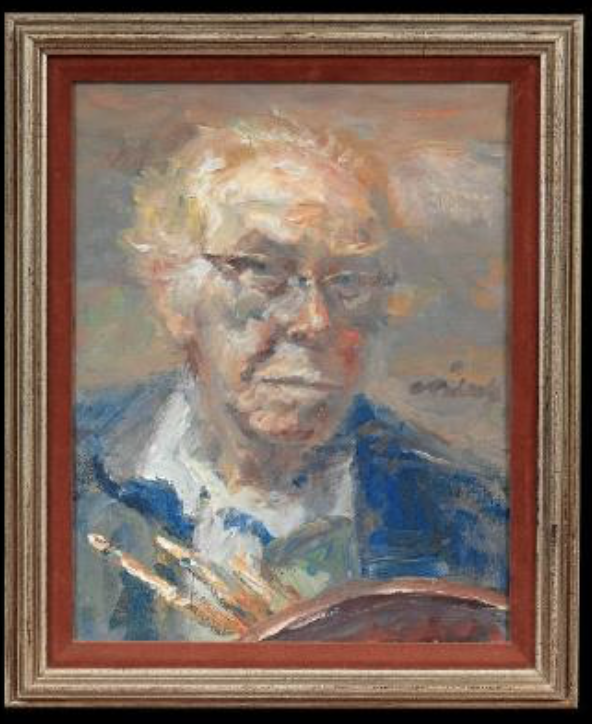

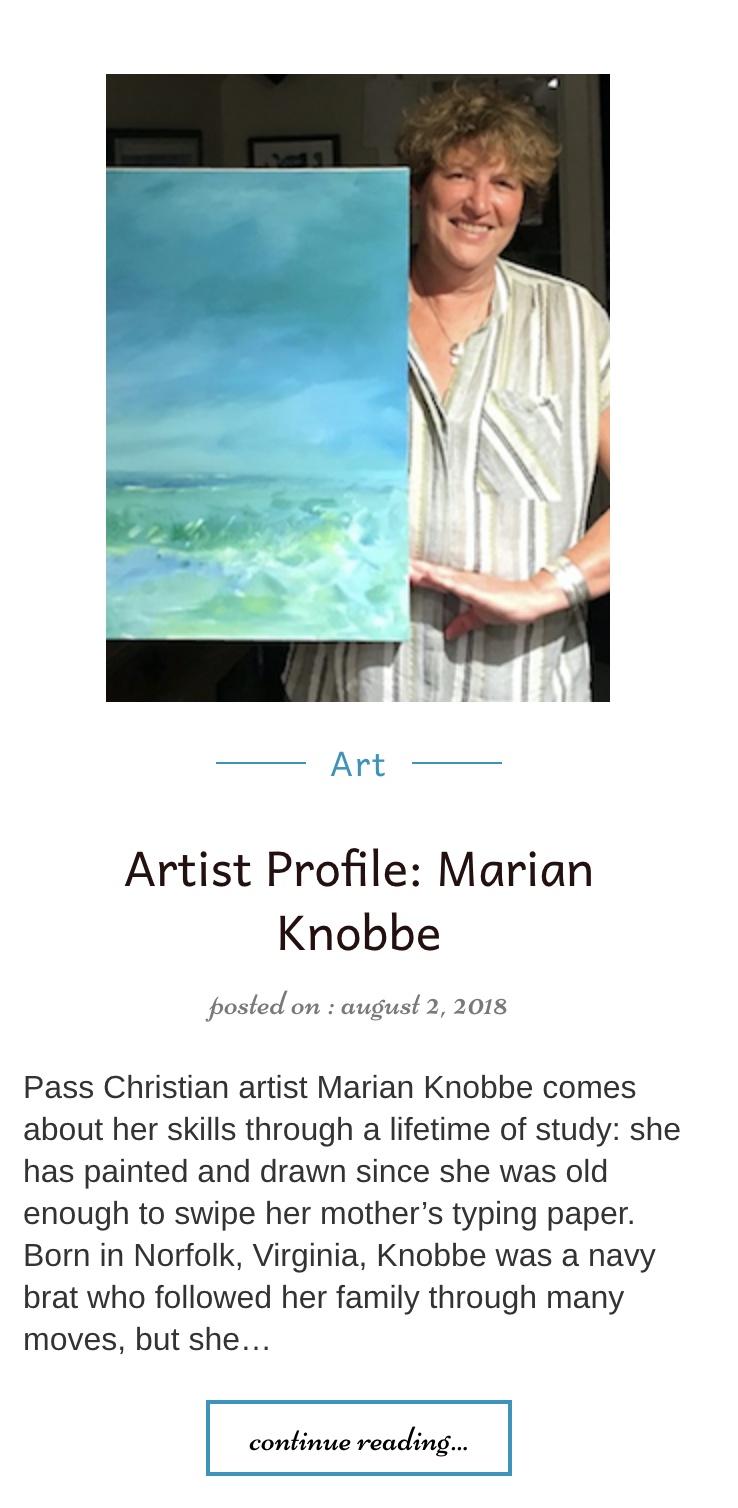

A new publishing enterprise seeks to highlight Gulf Coast art, culture and food, while providing opportunities for local writers. Meet The Cultured Oak creator, author Michael Warner.

-story by Lisa Monti

“There’s a rich talent pool of writers on the Gulf Coast, and historically has been for many years in New Orleans and on the Coast. And there are some good publishing outlets in Mississippi and Louisiana, but it struck me that right here along the Coast there is a lot of talent that’s not been tapped into really,” he said. Warner unexpectedly set out on the path to publishing while putting together a work of his own. “I was working on a project that turned into a book and I thought a good way to approach it would be to set up a publishing company and make it the first project out the door.”

That project is a newly published book. A Lyle Saxon Reader is a collection of stories by the legendary Times-Picayune reporter whose byline started appearing in the New Orleans newspaper around 1919.

Warner, a native of New Orleans, started working on the anthology back in November 2017. “A lot had been written by and about Saxon but his early works were largely ignored,” Warner said.

Warner had his interest on Saxon ignited while working on a biography of Charles Richards, a New Orleans artist who was born in the Mississippi Delta in 1909 and died in 1992.

“My mother, Jeanne Warner, knew him quite well. She was a longtime Bay St. Louis resident and she introduced me to him many years ago. I have almost 20 hours of taped interviews with him. His life was just fascinating.” The research led Warner to Alberta Kinsey, an early French Quarter artist who painted scenes of local courtyards, patios and buildings. “I was researching her life and it turns out she was a close friend of Lyle Saxon,” Warner said.

Writing is the newest layer is Warner’s varied career. He earned a Ph.D. in organic chemistry and did research in St. Louis before deciding to pursue a law degree and combine that with chemistry.

He then accepted a position in San Francisco, heading legal work at a Pfizer Pharmaceuticals research site. He retired from Pfizer a few years ago and now works as an attorney for a small biotech startup in San Francisco. Warner and his wife, Connie, divide their time among Bay St. Louis, the St. Louis area and San Francisco. Warner said his choice of The Cultured Oak name for his publishing effort is another bit of creative experimentation, tying the iconic Live oak with the South’s literary tradition. “It’s evocative of the region here and I wanted it to be evocative of literature.”

Warner is looking to expand The Cultured Oak’s offerings by attracting writers looking to be published.

“I’m hoping to find some neophyte writers along the Coast who might have an interest in submitting their writings for publication.” If you would like to be considered as a guest blogger, send your ideas to [email protected] along with some information about yourself. No experience is needed, just a good idea. Sample a few Cultured Oak stories below!

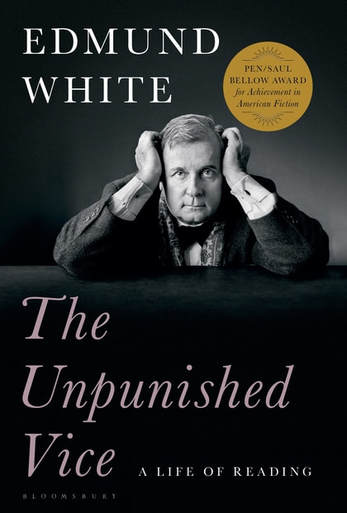

Pack your bags AND your books. Writer/bookstore owner Scott Naugle doesn’t leave home with them.

Writing in The Unpunished Vice: A Lifetime of Reading, Edmund White shares a similar sentiment, “If I watch television, at the end of two hours I feel cheated and undernourished (although I’m always being told of splendid new TV dramas I haven’t discovered yet); at the end of two hours of reading, my mind is racing and my spirit is renewed. If the book is good…” Edmund White is a novelist, biographer and essayist. His fiction includes The Beautiful Room is Empty, The Farewell Symphony, and Fanny: A Fiction. He has penned biographies of Marcel Proust and Jean Genet. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1940 and resides in New York City. Employing his remarkable and voluminous memory, White recounts his reading and the impact of the works on his life and world view as he matured from teenager to septuagenarian.

White recalls his first reading of William Faulkner, and credits him with “expand[ing] his concept of the novel” as an art form while also performing as social commentary. He checks Faulkner though on his “verbal, seemingly drunken absurdities” as demonstrated by this phrase, among others, from Absalom, Absalom, “That aptitude and eagerness of the Anglo-Saxon for complete mystical acceptance of immolated sticks and stones.”

I packed The Unpunished Vice for a recent flight to Washington, D.C., connecting through Atlanta. Traveling with books requires planning. I spend far more time fussing over what I want to take along to read than I do with tossing a few clean shirts and socks in a Samsonite. My luggage invariably holds two or three books, more if the trip is longer, and one or two in my backpack that I carry on the plane.

Non-fiction is a more convenient read while traveling, preferably a book of essays such as White’s. Literary fiction necessitates longer periods of uninterrupted thought. A fifteen or twenty page essay is ideal for the short hop from Gulfport to Atlanta.

Once, I made the error of packing five books, including two hardbacks, in my suitcase. I was pulled out of the airport security line by a TSA agent after “suspicious objects” were detected in my suitcase that I just placed on the conveyor belt to move through the scanning machine.

“I need you to remove all the books that are in your suitcase,” bellowed the brusque TSA agent. His sallow skin matched the worn brown of his stretched polyester pants as he attempted to impart an air of authority by a wider than natural stance while crossing his arms.

“Why?” I asked. “You may have hollowed out the insides of the books and placed prohibited or dangerous substances in them. It’s not normal to have that many books in a bag.” Advanced age teaches me to hold my tongue, but not my thoughts. “Oh, ok," I said while thinking, Yes, the books do contain dangerous things. They are called ideas. When no incendiary chemicals were found in the books, with a wary eye, the deflated TSA agent waved me through. I don’t fare well either at times in the seat mate lottery. On a more recent flight, while reading The Unpunished Vice, ensconced in words and intriguing thoughts, Flem Carbuncle (I don’t know if that was his name, but it fits) sat beside me, overfilling the narrow seat.

“What's that there you're reading? A book?”

“Yes,” I said curtly. “My grandmother was from up north there in Tennessee and she wrote a little book once before she died,” he blathered, oblivious to the fact I was not fully listening. “Oh, that’s interesting.” “The little book was about the pixies and faeries that she believed visited her at night in her sleep and gave her advice when she was upset or worried.” Contrary to the title of White’s book. I felt I was being punished for my vice of reading. Aloft, the clouds thousands of feet below, after the stewards and stewardesses have docked the beverage cart and my overhead reading light is the one beacon in an otherwise dark cabin on a red eye flight, I think of this passage from a letter written by Virginia Woolf to a friend, “Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.”

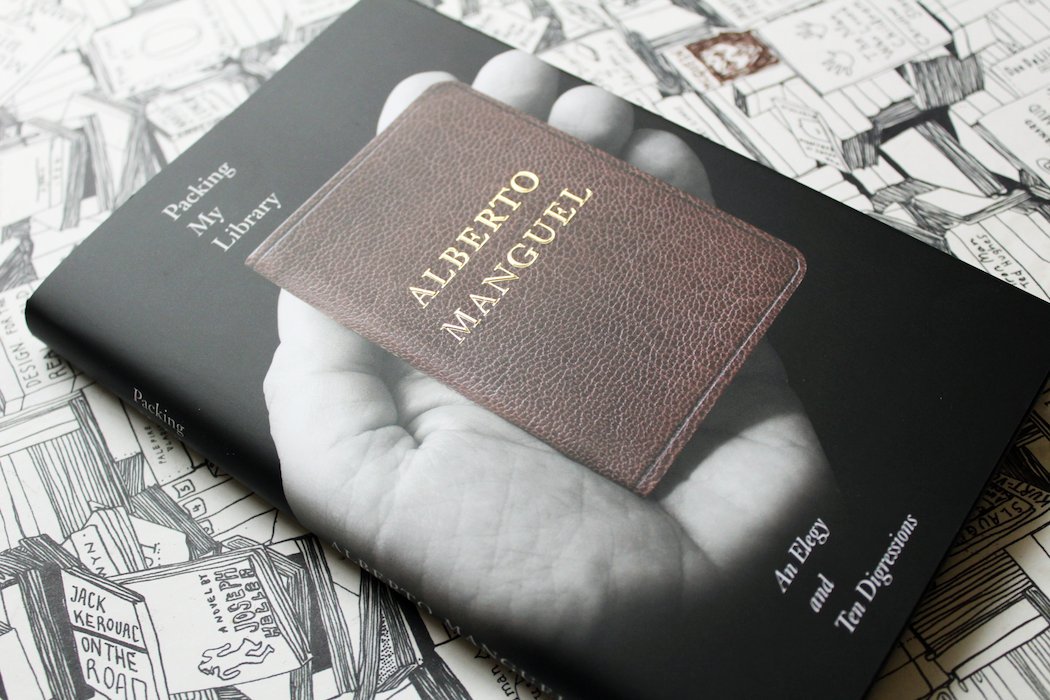

When writer/bookstore owner Scott Naugle begins to pack his library, he finds he's not the only book-lover to be transported by the task.

- by Scott Naugle

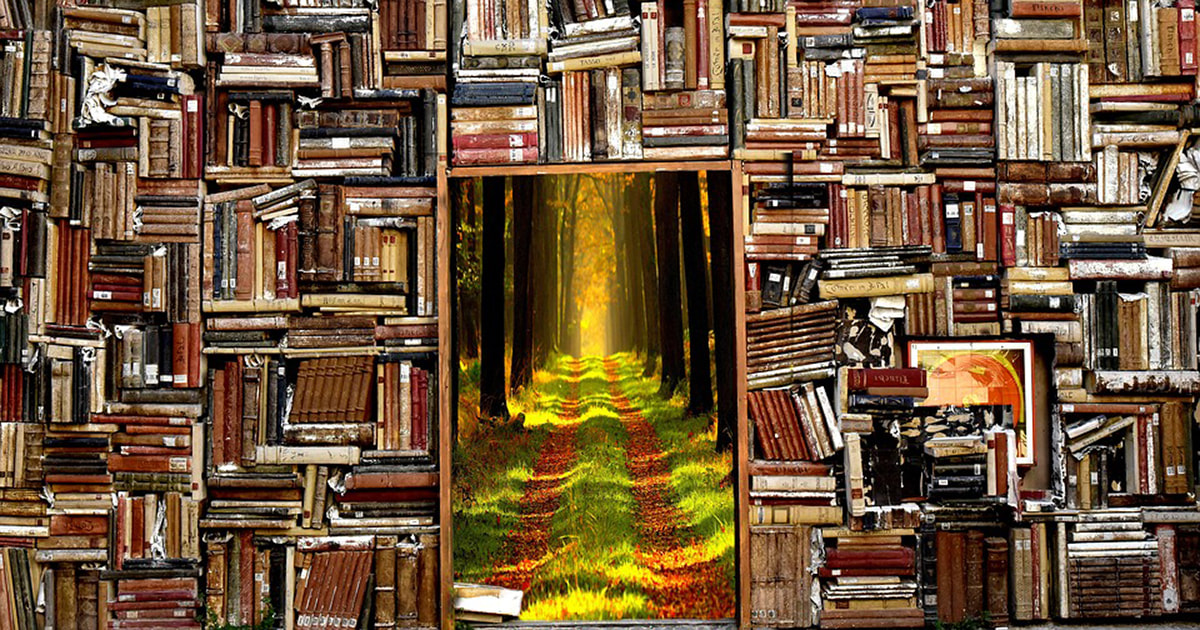

When the writing, fiction or nonfiction, connects with me at the deepest intellectual and emotional levels, often decades ago, so too does memory include the physical surroundings, the room, the chair, the palpable sense of reading that specific book.

A book is not read in a vacuum, but rather it is a sticky, intellectual syllabic immersion into the limbic region of the brain, where memory is stored, dense and nuanced with smell, touch, sight, and sounds.

In Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions, Alberto Manguel notes a similar cognitive connection: “The books most valuable to me were private association copies, such as one of the earliest books I read, a 1930’s edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Many years later, memories of my childhood drifted back whenever I turned the yellowed pages.”

In the year 2000, Manguel and his partner purchased a medieval presbytery in the Poitou-Charentes region of France, renovating it into a personal library and home. In 2016, he was named director of the National Library in his native Argentina, necessitating the crating and moving of his extensive collection.

A few months ago, at an age when I should be downsizing rather than upsizing, we purchased a home, originally constructed in 1885, meticulously renovated to its original state, heart pine floors, beadboard ceilings, and white porcelain doorknobs, with, of course, the necessary 21st century upgrades including oversized bathrooms and a gas stove top (I’m staying away from the contraption) with enough jets to launch a small aircraft. Manguel writes elegantly and passionately about packing and shipping 35,000 books overseas. I only moved 5,000 books less than two miles down East Second Street in Pass Christian. I’m a minnow to his white whale.

To carefully box for the short journey, I pulled a four-volume set of Edgar Allan Poe from the shelf. It was already old and loose in its binding when I purchased it for a few dollars at a flea market over forty years ago.

“There are few persons who have not, at some period in their lives, amused themselves in retracing the steps by which particular conclusions of their own minds have been attained,” wrote Poe in The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Rereading it in the present, I was transported back to Somerset County, Pennsylvania, on a snowy January evening. Pushing midnight, I was sitting upright in bed on top of the tan and blood red striped bedspread in my bedroom, the fingers of the frigid winter air creeping in through the loose wooden window frame, rattling it when the snowy wind whooshed against it. The room was illuminated by the single bulb in my gooseneck reading lamp, casting menacing shadows on the far wall, as I turned the pages. Downstairs, the late local television news was droning on, the imperceptible words of the stern newscaster like a distant wailing. Again Poe, “Madmen are of some nation, and their language, however incoherent in its words, has always the coherence of syllabifaction.”

A few weeks ago, during our humid August, I packed several books by and about Toni Morrison. In The Bluest Eye, I had marked this passage, “Each night, without fail, she prayed for blue eyes. Fervently, for a year she had prayed. Although somewhat discouraged, she was not without hope”

I was transported to my study in Jackson, Mississippi, first reading this novel twenty-five years ago, sitting in a green leather recliner, the white Berber carpet contrasting sharply with the blue walls. Beignet, my small black poodle, was sleeping against me. It was a Sunday afternoon and I just finished several hours of working in the yard. The sun beamed through the double window at an angle with the effect that one half of my study was brightly lit while the other half remained in dusky blackness. It was as if a solid impenetrable line separated the two parts of the room into opposing worlds. Morrison’s use of language, the subtext, and how subtext overwrites a facile and simple interpretation of a story, captivated me. It was as if I was learning to read again for the first time. As Morrison explains in a series of essays, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, I would discover years later, “In other words, I began to rely on my knowledge of how books get written, how language arrives; my sense of how and why writers abandon or take on certain aspects of their project… of a kind of willful critical blindness.” From The Bluest Eye: “Outside, the March wind blew into the rip in her dress. She held her head down against the cold. But she could not hold it low enough to avoid seeing the snowflakes falling and dying on the pavement.” Every reading of this passage then and now is weighted with my guilt at not doing enough to destroy the unfairness thriving in our world.

I’m in the present, late October, relaxing for the first time in the upstairs library, early evening, in our new home. The two poodles, Gonzo and Snopes, are asleep. Glancing around the room, my eye snags every few seconds on a title, memories of how the book made me feel in a time and place of the past, how each informs my sense of self.

Jorge Luis Borges’ Collected Fictions rests behind me on a high shelf. From his short story The Library of Babel: “When it was announced that the Library contained all books, the first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure.”

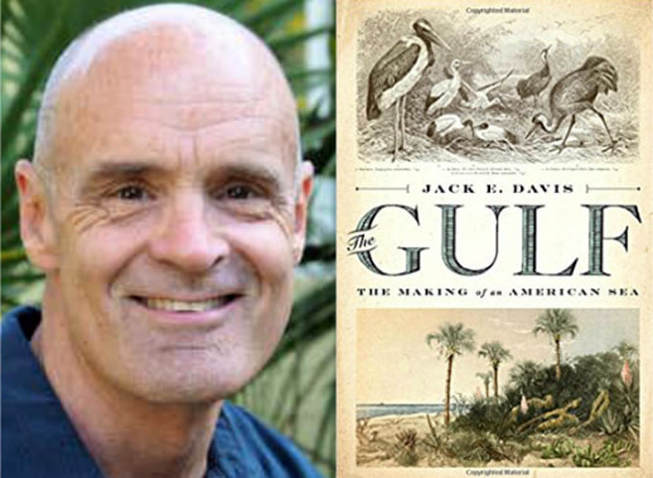

A sweeping new narrative explores the Gulf of Mexico, taking readers from its exotic pre-history to its precarious present.

- story by Scott Naugle

Davis continues with a foreboding close to the paragraph, “The doomed megafauna struggled for survival against a common implacable predator – humans with spears and shell clubs – and against a changing climate. Lost causes both, as it turned out.”

Between his opening comments on the plate tectonics forming the Gulf of Mexico and the present day, Davis tells a rip-roaring, relevant, concise, beautifully written history of the gulf. He is a polymath covering every aspect from early twentieth-century visits by the painter Winslow Homer and poet Wallace Stevens; Spanish, French, and English exploration; the dawn of commercial fishing; the advent of tourism; and the BP oil spill.

Jack Davis spent a lifetime preparing to write this monumental work. He recalls his childhood romping on the beaches and marshes along the coast of the Florida panhandle, studying the birds while listening to the melodious rhythm of the surf. He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of South Florida and a doctorate from Brandeis University. Davis currently teaches environmental history and sustainability studies at the University of Florida.

Davis was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for History for The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.

While the research is meticulous and expansive ranging from social history to wildlife and the coastal flora, it is the narrative, the people and story of the gulf, bringing this history to life like a multi-layered novel. “Among the most scintillating of sights were fish in schools as long as freight trains, running with the invisible gulf tide” was the scenery encountered by Winslow Homer in 1904, as he traveled with “rod and reel … and paints and brushes” as described by Davis. A century later, Joseph Boudreaux, earning a meager living as a commercial fisherman, lamented over the effects of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, erosion caused by commercialization and inland effluents, and the unnatural effects of levees and dams, “that’s when the erosion’s going.”

Davis explicates, “If you were a fisher, every day was a day not unlike the heron that fished the marsh - a quest to make the quota for sustenance.” The gulf, over-used and exploited, has exceeded its quota, depleted and polluted. We are modern-day versions of our ancestors with “spears and shell clubs,” employing instead rigs, nets, and chemicals against the gulf.

The Gulf is the 2018 selection for One Book One Pass, a community reading initiative where everyone reads the same book and has the opportunity to hear the author speak. In 2016, the first year for the program, Erik Larson spoke about the best-selling “Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania.” Last year, National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward discussed “The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race,” a collection of essays edited by Ward.

For Larson and Ward, the community turnout was both overwhelming and enthusiastic. The Randolph Center in Pass Christian was stacked to standing room capacity to hear each author speak and answer questions about their work.

The date for this year’s presentation by Jack Davis is Wednesday, October 17th 7:00 PM at the Randolph Center, 315 Clark Avenue in Pass Christian. It promises to be another informative and fascinating evening.

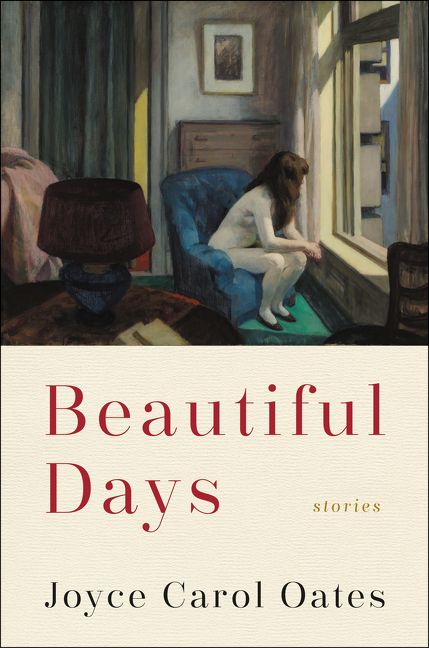

Writer Joyce Carol Oates, author of more than sixty books and one of the most esteemed living American writers, will be visiting the Mississippi coast in July, signing her two newest publications at Pass Books.

- by Carole McKellar

Born in 1938, Oates published her first book in 1962. She taught creative writing at Princeton University from 1978 until she retired in 2014. Oates has won awards for her writing, including the National Book Award for “them” in 1969, two O. Henry Awards, and the National Humanities Medal. Her novels and story collections were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize five times.

Beautiful Days, published this year, consists of eleven stories. All of the stories previously appeared in respected periodicals but never appeared together. The subject matter is diverse including stories of extramarital affairs and suicide alongside fantasy. “Les Beaux Jours” is about a vulnerable girl desperate for the love of her absent father. She is drawn into a Balthus painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The subject imagines herself a prisoner inside the painting and writes a letter to her father begging him to rescue her from the cruelties imposed by the Master. In “Undocumented Alien” a Nigerian student is saved from deportation by participating in a classified research project. A chip implanted in his brain adversely affects his cognitive function and drives him to madness. This chilling story describes a young man fighting to maintain his humanity. Although the eleven stories are disturbing and generally dark in tone, I liked this collection. Oates is a skilled and imaginative writer. Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense is on my nightstand, and I look forward to reading the six creepy tales within. The first story, “The Woman in the Window,” is a reimagining of Edward Hopper’s painting, ’11 A.M., 1926,’ which features a woman sitting in an apartment window naked except for high heels. That painting is on the front cover of “Beautiful Days.” At eighty years old, Joyce Carol Oates continues to earn the respect of readers and writers alike. She avoids celebrity and has cultivated a reputation for hard work and professionalism. Oates is regularly discussed as a strong contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature. I look forward to meeting Ms. Oates at Pass Books and consider it an honor for the coast to have such a literary icon visit.

A moving new novel by award-winning writer Minrose Gwin centers around the tragic Tupelo tornado of 1936. The Shoofly Magazine's book columnist Carole McKellar interviews the author and reviews the book.

Minrose Gwin will be at Pass Christian Books on Thursday, March 22 at 5:30 pm. She will talk about Promise and sign books. I hope to see you there, but, if you can’t attend, call the bookstore and have a copy signed for later pick up.

Although the characters are fictional, Gwin uses her intimate knowledge of Tupelo landmarks to provide readers with a vivid picture of the setting. Some places like the Lyric Theater and Reed’s department store remain in business today as they were in 1936. The Lyric Theater served as a makeshift hospital in the aftermath of the tornado.

The central characters are Dovey Grand’homme, an African-American laundress, her granddaughter, Dreama, and Jo McNabb, a white girl of sixteen. The McNabbs are a prominent Tupelo family, and Dovey does their laundry. She hates the family because Jo’s brother raped Dreama without punishment or legal consequences. Dreama became pregnant as a result of the rape and gave birth to a son named Promise. The characters in Promise are fully developed and complex. They display all too human emotions including guilt, hatred, and pride. I particularly liked Dovey who showed strength and resilience against a life of hardship. Jo and Dovey’s family are bound together by the horrific rape and their struggles after the storm. The events depicted take place between Palm Sunday, April 5, 1936 and the following Friday. The story is told alternately from the point of view of Dovey and Jo. After the storm, Dovey searched frantically for her family in the segregated makeshift facilities. She is eventually reunited with Dreama and her husband, Virgil, but they have to keep searching for Promise.

Jo’s story involves searching for her baby brother, Tommy. Jo's mother was seriously injured in the tornado and her father was not around. The two missing babies are at the heart of the story.

The depiction of destruction is drawn from actual photographs of Tupelo in the aftermath of the tornado. Gwin’s novel artfully creates an atmosphere and landscape that puts the reader on the broken streets with the characters and shares their suffering and despair. Her depth of research takes us to a lost time and culture. Minrose Gwin has a good ear for Southern phrasing and idiom. In that respect, she reminds me of Eudora Welty. I smiled when I read the phrase, “Katy bar the door” because my mother used that expression often when trouble was expected. I remember reading The Queen of Palmyra,* Gwin’s first novel, and thinking how true and familiar the characters felt to me. That book was also set in the Tupelo area. Minrose Gwin has been a writer all of her adult life. She began as a journalist, but found her calling as a teacher of English and creative writing at the college level. She most recently taught at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In addition to the two novels, she has written a memoir about her mother titled Wishing for Snow. In addition, Gwin wrote Remembering Medgar Evers about the slain civil rights leader who was murdered in 1963 outside his home in Jackson. I had the opportunity to ask Ms. Gwin a few questions which she kindly answered by email.

How long did it take you to write Promise? There must have been a lot of research that went into the story.

Promise really chose me. I was in the revision stages of another novel, when I learned that the stories I'd heard all my life about the tornado weren't complete--that the casualty figures weren't complete because members of the African-American community of Tupelo hadn't been included. This angered me and spurred me to write the novel, which I hope excavates the deeper devastation of racial injustice. Counting research, it took about 18 months. Since I grew up in this town, the landscape was the easy part. It was the fastest book I've ever written. Both The Queen of Palmyra and Promise deal with racism and its history in our state. You also wrote Remembering Medgar Evers. What influences led you to write about race in this way? Yes, race is a topic I've dealt with in my scholarly work as well as my fiction and memoir, from the very beginning. I am interested in history and how history shapes us, but my books, unfortunately, are as much about the present as they are about the past. I am white, but I was fortunate to have an African-American babysitter named Eva Lee Miller and to stay with her for extended periods in her home. During my formative years, I got to know her friends and family, their struggles, from inside her home, and I got the benefit of her considerable wisdom and saw the incredible power of her resistance to the racism that embedded the culture, and of course still does. We were in close touch until her death. She was and is a major influence in my life and writing. Did you hesitate to write in the voice of Dovey given the political climate today? By that I mean criticism of men writing in the voice of women or whites writing as African-Americans. I don't use the first person voice for black characters in The Queen of Palmyra or Promise. In the first book, the narrator is a white woman recalling the summer she was almost eleven, and in the second, there's an omniscient narrator relating the story from the alternative points of view of Dovey, the African-American great-grandmother, and Jo, the white girl. So we get the voices of the black characters through a filter. To my knowledge, no one has objected to that in my fiction. In writing both of these novels, I was trying to directly confront the social justice issues that remain with us today. I read about your memoir, Wishing for Snow, about your mother, a poet. Do you write poetry? Who are your favorite poets? There was a period in my life I wrote poems and a few were published. I've been told that my prose is poetic so there must be some link there. My favorite poets? Among contemporary poets, my favorites are Joy Harjo and Natasha Trethewey. I've always loved Keats, Stevens, and Dunne. How has your career as a journalist influenced your writing? My few years as a journalist were pivotal in so many ways. They acquainted me with tragedy. They taught me to get the words down on paper (now computer screen), even if they weren't perfect. Journalism taught me to check my facts. I like fiction that's grounded in facts--the Tupelo tornado in 1936, for instance, in the case of Promise. I like to get details right, like what blooms when and where, like historical detail. Journalism taught me to observe the world closely. Do you write every day? Writing every day is especially important when I'm writing a first draft because you have a certain momentum you have to keep up, a certain drive. What writers influenced you? I love Mississippi writers! I'm a Faulkner scholar, so he's been a big influence, also Welty, especially the visual in her work. I love her photography too. There's a photo she took of a laundress back in the 1930s that made me start shaping the character of Dovey in Promise. I've read all of Toni Morrison's work, and taught most of it, so she's been an important influence too. *Bay St. Louis residents will be interested to know that a portion of The Queen of Palmyra was written in the Webb School owned by Ellis Anderson and Larry Jaubert. Gwin was working in New Orleans at the time and used Webb School as a writing getaway.

Limited on time, but love a good read? Shoofly Magazine book reviewer Carole McKellar lists her favorite 2017 books - and gives "best of" lists from the New York Times, Publisher's Weekly and the Boston Globe.

— Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders was my favorite book this year. Saunders is famous for his stories, but his first novel won the Man Booker Prize. This novel takes place in the graveyard housing Abraham Lincoln’s beloved eleven year old son, Willie. Souls trapped in purgatory, called the bardo in Tibet, view Lincoln visiting his young son and find hope for their own salvation. Funny, dark, and totally original, this book will always have a place on my shelf of favorites.

— News of the World by Paulette Jiles describes the journey of a hardened veteran of multiple wars and a child captured and raised by a Kiowa tribe. The child remembers nothing of her life wearing dresses or speaking English. The love and trust that develops between them during their arduous trek across the lawless post-Civil War West brought tears to my eyes. — Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout is set in the small Illinois town that was the hometown of Lucy Barton, whom we first met in Strout’s previous book, My Name is Lucy Barton. Strout is one of my favorite writers, and this novel doesn’t disappoint.

— Moonglow by Michael Chabon is a fictionalized account of the life of Chabon’s grandfather, an adventurous scientist, engineer, and entrepreneur. The story unfolds as the old man relates his life story during the weeks prior to his death.

— Persuasion by Jane Austen was published 200 years ago in 1817. As with other Austen novels, there are worthy heroines who prevail over greed and vanity. None of Austen’s novels are quick reads, but they are certainly worth the effort. — Swing Time by Zadie Smith traces the friendship of two girls growing up in public housing in London from childhood into middle age. They meet in a dance class and bond over the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Dance and music play a large role in this book.

— Upstream by Mary Oliver is a collection of essays that explores the reliance on nature in her creative process. Anyone who loves Oliver’s poems will enjoy these essays. In the first essay, Oliver writes, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

— Miss Jane by Brad Watson is a fictional account of an ancestor of Watson’s who grew up in rural Mississippi with a handicap that made an ordinary life impossible for her. Jane lived to an old age without bitterness or complaint. Her attitude in overcoming her handicaps was inspirational. — Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng starts with the death of a teenage girl. Lydia is the favorite child of Chinese parents who expect her to achieve what they were unable to. This book reads like a mystery while telling how loving families can completely misunderstand each other. — The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben and The Genius of Birds by Jennifer Ackerman will change how you look at the natural world. According to Wohlleben, trees in the forest are social beings who nurture each other and communicate danger through secretion of scent or sound vibrations. I risk boring my friends with information from The Genius of Birds, and force my husband, John, to listen while I read stories of navigation, nest building and feats of intelligence. These two books are remarkable.

The New York Times Best Books of 2017

Fiction

Publisher’s Weekly Top 10 Books

Fiction

Nonfiction

The Boston Globe’s Best Fiction of 2017

Borne by Jeff VanderMeer Blameless by Claudio Magris, translated from the Italian by Anne Milano Appel The Burning Girl by Claire Messud The City Always Wins by Omar Robert Hamilton Cockfosters by Helen Simpson The End of Eddy by Édouard Louis, translated from the French by Michael Lucey Exit West by Mohsin Hamid Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell Frontier by Can Xue, translated from the Chinese by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie House of Names by Colm Toibin Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders The Lonely Hearts Hotel by Heather O’Neill The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy My Cat Yugoslavia by Pajtim Statovci, translated from the Finnish by David Hackston Pachinko by Min Jin Lee The Power by Naomi Alderman Savage Theories by Pola Oloixarac, translated from the Spanish by Roy Kesey Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enríquez, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

2018 is shaping up to be another great reading year.

A Case for Reading Fiction

Want to fight the onset of dementia? Pick up a good novel. Science also shows that reading literary fiction increases empathy and enhances the ability to see another perspective.

- by Carole McKellar

The most interesting research I’ve read is the work of psychologists Emanuele Castana and David Kidd published in the magazine “Science” in 2013. The researchers gave participants different reading assignments: excerpts from popular fiction, literary fiction, and nonfiction.

Popular fiction included mysteries, romances, and adventures. Literary fiction is difficult to define, but the test administrators chose works by award winning or canonical writers. After reading the texts, the subjects were given a test which judged their ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of others. In other words, would the participants demonstrate a greater capacity for empathy. The results indicated that the nonfiction and popular fiction readers did not score high on measures of empathy. The readers of literary fiction have a far greater ability to relate to the lives of others. According to researchers, readers of literary fiction must infer the feelings and thoughts of characters. That is, they must engage “Theory of Mind processes.” The authors define Theory of Mind as “the human capacity to comprehend that other people hold beliefs and desires and that these may differ from one's own beliefs and desires.” Popular fiction portrays predictable characters and situations which only reenforce the reader’s expectations. These results might surprise those who assume that nonfiction is the genre that would best promote understanding. The Common Core State Standards Initiative, a controversial education initiative in wide use throughout the United States, details what K-12 students should know in language arts and mathematics at the end of each grade. Common Core curriculum guides emphasize nonfiction and downplays the importance of fiction.

It is concerning to me that parents and educators consider fiction to be less important to a child’s literacy than nonfiction. The stories most meaningful to me as a child were all make-believe. Reading fiction helps children understand what others are thinking and feeling. Such understanding could better prepare children for the complex world we live in today.

This topic reminds me of a wonderful novel I read recently titled “Exit West” by Moshin Hamid. It tells the story of two young people, Saeed and Nadia, in an unnamed country torn apart by civil war. They are forced to flee their homeland, and they eventually make their way to the United States. The remarkable thing about this book is the way the author expresses the tragedy of exile and dislocation from family. It’s a heart-wrenching story of loss which gave me a deeper understanding of the plight of refugees. “The Underground Railroad” by Colson Whitehead comes to mind as well. It tells the story of Cora, a young runaway slave, who escapes on a railroad that runs through underground tunnels. The depiction of her journey is harrowing and kept me engaged. “The Underground Railroad” won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Both novels feature magical elements. In “Exit West,” people pass through doors to find themselves in another country. “The Underground Railroad” asks readers to accept the idea that trains ran through tunnels built in the South. Such plot devices did not diminish the strong depiction of complex characters in difficult situations. Their stories were different from my own life, and they challenged me to understand their experiences. The case for reading fiction is strong. Reduced stress, greater empathy, increased vocabulary, and more creativity are good reasons to pick up a novel and dive in. In the words of American novelist, Joyce Carol Oates: “Reading is the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another’s skin, another’s voice, another’s soul.” A Darker Sort of Vision

There's Utopia and Dystopia - the perfect world versus one that's gone very, very wrong. Book columnist Carole McKellar looks the literature that has us cringing, but keeps us coming back for more.

Published in 1726, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels combines utopian and dystopian elements. Lemuel Gulliver traveled to countries with simplistic utopian qualities but others places he visited had dystopian aspects. His encounter with savage societies like the Yahoos sours Gulliver on human nature, and he changes from an optimist to a misanthrope by book’s end. This book was a favorite read during my college years with its satirical study of the good and bad elements of society.

Studying the timeline of dystopian fiction is useful in order to understand its popularity today. A guide to the history of dystopian fiction was posted by Patrick Brown on Goodreads in 2012. From the 1930s through the 1960s, dystopian literature was inspired by World War II, fascism, and communism. Controlling governments, loss of freedom, and the possibility of mass destruction were the inspiration for these classics: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932) It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (1935) 1984 by George Orwell (1949) Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1950) Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1952) On the Beach by Nevil Shute (1957) A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962) The second wave of dystopian fiction was concerned with identity politics and its anxiety about the human body. Novels from this period include: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985) V is for Vendetta by Alan Moore & David Lloyd (1988) The Children of Men by P.D. James (1992) Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005) Young Adult dystopian novels feature strong central characters in extreme circumstances. The phenomenal success of The Hunger Games trilogy spawned a multitude of novels that showcase a young hero or heroine successfully fighting against authoritarianism. Teens may worry that they face a dark, chaotic world with perpetual wars and ecological disasters. Dystopian fiction provides young people with exemplars of bravery who rise above adversity. Examples of the genre, which are often written as series, are: The Hunger Games (2008) by Suzanne Collins Divergent by Veronica Roth (2011) The Giver by Lois Lowry (1994) Uglies by Scott Westerfeld (2005) The Maze Runner by James Dashner (2009) The Unwind Dystology by Neal Shusterman (2009) Other dystopian literature that I recommend for good writing and compelling stories include: The Lorax by Dr. Seuss (1971): This “children’s book” features a warning of the effects of environmental degradation. The Road by Cormac McCarthy (2006): Awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize, this book tells the story of a man and his son’s journey after surviving an unspecified catastrophe destroys almost all life on earth. Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014): After a pandemic kills most of the world’s population, a troupe of traveling actors makes their way across the Great Lakes in search of survivors. American War, a debut novel by Omar El Akkad (2017): This chilling book takes place in 2075 and presents a second civil war in an America facing environmental destruction and societal collapse. Stories of disaster and misery may not appeal to every reader, but there are reasons for their popularity. Many are well written with intricate plots and admirable characters. Through them we see aspects of our own society, but the elements are more extreme. It’s interesting to imagine how we would react were we placed in similar circumstances. There is anxiety in today’s society and a concern for our future. Stories of dystopian societies make readers aware that average people can be heroic and find solutions to problems.

The TED talk below is only five minutes and gives an interesting overview of dystopia.

Fathers in Literature

Book columnist Carole McKellar takes a look at some of the best and the worst fathers in modern literature - and in real life, with Every Father's Daughter, edited by Pass Christian author Margaret McMullan

The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar was picked by The New York Times as one of the five best nonfiction books of 2016. It tells the true story of Matar’s father, who was kidnapped by Quaddafi’s forces and thrown into a secret prison in Libya. His family never saw him again, and the book tells of a son’s search for the truth of his father’s death and the tragic lives of Libyan refugees in a well-written story of familial love.

In The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti (from Parnassus Book First Editions Club) the father is a career criminal who tries to provide his daughter with a normal life. The story moves back and forth over time and weaves the story of the twelve times Samuel was shot during his life with his intense love for his dead wife and child. This book reads like a thriller, and I loved it.

Other admirable fathers in fiction:

Some less than admirable fictional fathers are:

Real-life fathers, both good and bad, are eloquently portrayed in Every Father’s Daughter: Twenty-four Women Writers Remember Their Fathers selected and presented by Pass Christian author, Margaret McMullan. I enjoyed essays by some of my favorite writers, including Alice Munro, Lee Smith, and Jane Smiley, but I equally enjoyed stories by writers unknown to me. Melora Wolff’s essay brought strong memories of my father when it began:

Maybe we remembered hugging the fathers when we were little girls and they were like trees, and we balanced on the tops of their shoes; maybe we remembered lifting out arms above our heads and waiting for our fathers to lift us up as if we were little ballerinas, into the air where we spun and squealed. The forward by Margaret McMullan is worth the price of the book. She wrote about her relationship with her father and their love of books: “When we talked about a book, we were always talking about important things.” If you are fortunate to have a living father, please enjoy one of those hugs described above. If, like me, you no longer have a father in your life, buy Every Father’s Daughter and read all day on June 18. Or, you could watch To Kill a Mockingbird and enjoy Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch, who exemplifies the best of fatherhood. For fathers who read this article, Happy Father’s Day. Jobs Writers Do

J.D. Salinger was the activities director on a cruise ship? William Faulkner as a bridge playing postmaster? Book columnist Carole McKellar takes a look at the day jobs of some of the world's finest writers.

Several well-known writers held full-time jobs in fields related to literature. Toni Morrison remained an editor at Random House and taught university literature classes while her novels were winning prizes and legions of readers. Virginia Woolf and her husband, Leonard, created and ran Hogarth Press, which is now an imprint of Random House.

Jorge Luis Borges, Argentine writer, and Philip Larkin, poet, were librarians. T.S. Eliot, one of the twentieth century’s major poets, taught school, worked at Lloyd’s Bank, and later joined a publishing company responsible for publishing English poets like W.H. Auden and Ted Hughes. Frank McCourt, famous for writing Angela’s Ashes, taught high school English in New York.

There is a tradition of physician writers dating back to antiquity. In mythology, Apollo was the god of both poetry and medicine. Perhaps the doctor’s role as observer allows a unique perspective of the human condition.

I became interested in the idea of doctors who are also authors after reading When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. A gifted neurosurgery resident, Kalanithi developed lung cancer at the age of 36 and died while writing the book. His gifts as a writer make the book shine as he details his life and impending death. He earned a master’s degree in English literature from Stanford University before following his love of science into medicine. Kalanithi’s life plan was to practice medicine while young, and to follow that with a second career as a writer. This book is beautiful and haunting, and I recommend it highly. Abraham Vergese, M.D., wrote the foreword to When Breath Becomes Air. Vergese stated that Paul Kalanithi’s “prose was unforgettable. Out of his pen he was spinning gold.” That is remarkable praise from any reviewer, but it carries extra weight coming from Vergese, the author of one of my favorite books, Cutting for Stone. Published in 2009, Cutting for Stone chronicles the lives of conjoined twins born in Ethiopia to an Indian mother who dies in childbirth. Vergese is an Indian physician born in Ethiopia, and his novel features much about the political climate and medical practices of the country.

More published authors who were trained as healers include:

In addition to long-term careers, it is interesting to learn about early jobs authors held and to imagine the effect of those jobs on subsequent writing. Agatha Christie worked in an apothecary, which provided knowledge of pharmaceuticals she later used in her mystery stories.

George Orwell was an Indian Imperial Police Officer until he contracted dengue fever and was sent back to England to recover. J.D. Salinger was the activities director on a luxury Caribbean cruise ship. John Steinbeck was a tour guide and manufacturer of mannequins. Kurt Vonnegut opened a Saab car dealership. After graduating from college with a degree in English, Stephen King couldn’t find a teaching job so he became a high school janitor. He said the movie Carrie was inspired during his time cleaning girls’ locker rooms. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, worked as a janitor in a mental hospital and tested LSD for a government-sponsored study. William Faulkner was a mailman (click here to read his spectacular letter of resignation), and Harper Lee worked for a while as an airline reservation clerk. The writers mentioned here achieved success through hard work and perseverance. Offering advice to those who aspire to become writers, Stephen King said, “If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.” Novelist Jack London wrote, “You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” I am an enthusiastic reader, and I try to write something every day. I enjoy looking at my old journals, filled with snippets of poems or observations about the day-to-day. I hope you take inspiration from these fine writers and don’t let your day job keep you from writing. The Making of a Book

The publication and printing of a book is a complicated process. Shoofly book writer, Carole McKellar, demystifies the process.

The back cover is reserved for favorable comments about the book or a previous book by the same writer. A recommendation by a famous author or media outlet like The New York Times Book Review can make a big difference in a book’s sales. The front flap of the cover has a brief synopsis of the book with information that may also appear in abbreviated form on the back cover. The back flap is reserved for a picture of the author and some biographical information.

The interior of most books follows a certain order. The end papers, or leaves, are the blank pages in the front and back of a book. Some end pages are plain paper, but many contain graphics such as maps or drawings related to the contents. The half-title page contains only the book’s title followed on the next page by other books by the author. The title page states the author’s and the publisher’s name in addition to the title. The copyright page, on the back of the title page, contains the year the copyright was issued for publication, the publisher’s address, the ISBN (International Standard Book Number), the printing numbers, and the =Library of Congress catalogue information.

Writers apply for a copyright to ensure that their work is protected from theft or unlawful use. The U.S. Copyright Office requires a written application, a filing fee, and a copy of the book. The copyright, once issued, endures for 70 years after the author’s death. After that date, the book becomes part of the public domain. Since the works of Shakespeare and Jane Austen are in the public domain now, we are free to quote them without paying money to their estate. Visual arts, performing arts, and digital content are also eligible for copyright protection. My current favorite book, “Upstream” by Mary Oliver, published by Penguin Press, has a noteworthy motto on the copyright page: Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The United States authorizes a private agency to issue ISBNs to books to facilitate tracking and distribution. Without an ISBN, books cannot be sold to bookstores or libraries. Once the application is made, a 13 digit ISBN number is issued for each edition of a book including e-books, international editions, and audiobooks. Books published prior to 2007 have 10-digit ISBN numbers while those published later have 13 digits. Books may be registered with the Library of Congress, but registration is only necessary if the book will appear in libraries. Many self-published books aren’t registered. The U.S. Copyright Office is housed within the Library of Congress building in Washington, D.C, so all copyright records are stored there. As I mentioned in a previous column I joined the First Editions Club of Parnassus Books in Nashville. They send me a signed first edition of their choosing each month. Some books have “First Edition” printed on the copyright page, but that’s not true of all first editions. The printing numbers on the bottom of the page are more reliable indicators of edition number. Some numbers are in order 1-10, but frequently there is a nonsensical arrangement of numbers.That really doesn’t matter because you only need look at the lowest number to determine the print edition of your book. In the front of my book, “A Gentleman in Moscow” by Amor Towles, the printing numbers read like this: 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2. I knew that I had a true first edition because of the number 1. Another first edition in my collection, “My Name is Lucy Barton” by Elizabeth Strout, had the numbers arrayed this way: 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1. A friend recently gave me a copy of “Paris to the Moon” by Adam Gopnik which was first published in 2000. I know it was a popular book because the printing numbers were 34 36 38 39 37 35, which meant that I had the 34th edition of the book.

The dedication page allows the author to acknowledge people important to them. Few dedications explain the reason for the dedication and only state names. One of my favorites was the dedication in “Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin,” a collection of essays and stories by humorist, Calvin Trillin. It reads, “My wife, Alice, appears as a character in many of these pieces. Before her death, in 2001, even the pieces that didn’t mention her were written in the hope of making her giggle. This book is dedicated to her memory.”

Acknowledgements may come at the beginning or end of the book and provide a place for the author to thank people who were helpful with the book. They may include family, friends, agents, and/or professional colleagues. The end of the book may contain a glossary, bibliography, index, and/or appendix, but these are usually found only in nonfiction books. An item that often appears in the back of the book is ‘A Note About Type’ which explains the typeface and can be pretentious as in the following from “Paris to the Moon”: The book was set in Fairfield, the first typeface from the hand of the distinguished American artist and engraver Rudolph Ruzicka (1883-1978). In its structure Fairfield displays the sober and sane qualities of the master craftsman whose talent has long been dedicated to clarity. It is this trait that accounts for the trim grace and vigor, the spirited design and sensitive balance, of this original typeface.

The “Big Five” book publishers in the United States contain multiple divisions, or imprints, which can seem like a maze to the average reader. Below are the “Big Five” and some of the imprints within them:

• Hatchette Book Group - Little, Brown, and Company; Orbit • Harper Collins - William Morrow; Avon Books; Broadside Books; Ecco Books; It Books; Newmarket Press • McMillan Publishers - Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Henry Holt and Company; Picador; St. Martin’s Press, • Penguin Random House has nearly 250 imprints and publishing houses. Some of the most well-known are: Random House Publishing Group, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group; Crown Publishing Group; Penguin Group U.S.; Dorling Kindersley (DK) • Simon & Schuster - Scribner; Touchstone; Atheneuum In addition to the big publishing houses, there are small presses that publish writers who may not otherwise get accepted by the larger houses. Many small presses, like Milkweed Editions and McSweeney’s, are nonprofit organizations that publish new and emerging writers. Coffee House Press, another nonprofit press, has published more that 300 books, with over 250 still in print. Coffee House is a favorite of mine because they have the most interesting and artful book covers. Without small presses, talented writers would not receive the opportunity for discovery. More than 300,000 books were published in the United States in 2013, the last year I could find statistics. The information was provided by The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which monitors the number and type of books published per country each year as “an important index of standard of living and education, and of a country’s self-awareness.” Many more books are self-published, but those are not often found in bookstores or libraries. According to the Association of American Publishers, almost $28 billion in revenues were generated by the sales of books in all formats. Unit sales of print books rose 3.3% in 2016 over the previous year, so the book is far from extinct. According to Nielsen BookScan, which tracks about 80% of print sales in the U.S, total print unit sales reached $674 million, marking the third straight year of growth. We read books for many reasons. Whether we read to learn more about the world and our place in it or simply for entertainment, understanding what goes into the making of the book adds to the experience. Best Books of 2016

Local book aficionado Carole McKellar polls other avid readers in the Bay to compile a "best of" list to help you find books you'll enjoy reading - and gifting - in the year ahead.

Some titles I read in 2016 were critically acclaimed, but others I enjoyed were not. Some were current while others were quite old. I read Emma by Jane Austen for the first time to celebrate its 200th anniversary.