Thacker Mountain Radio Show host Jim Dees’ book recounts the furor over a Faulkner statue in the fabled author's hometown.

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

After two months in French lockdown, the author finds herself experiencing culture shock on her return to the States.

- Story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

Mourning John Prine in France, where the author's extended stay turned into an indefinite lock-down.

- Story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

Confined to a cottage in a countryside village, the writer gives an on-the-ground report of drastic changes in a timeless place.

- Story and photos by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

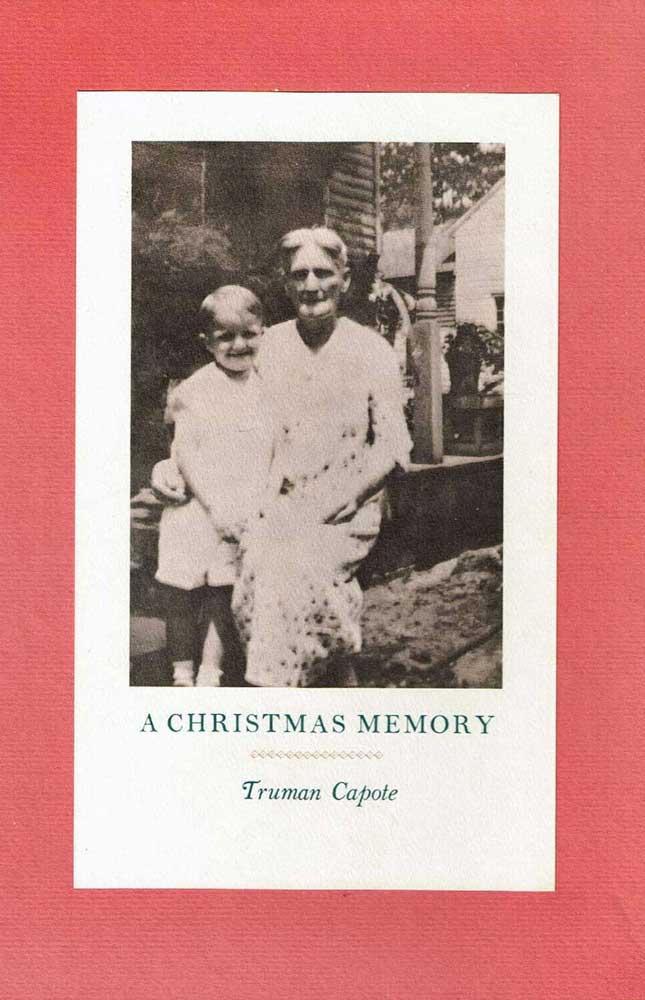

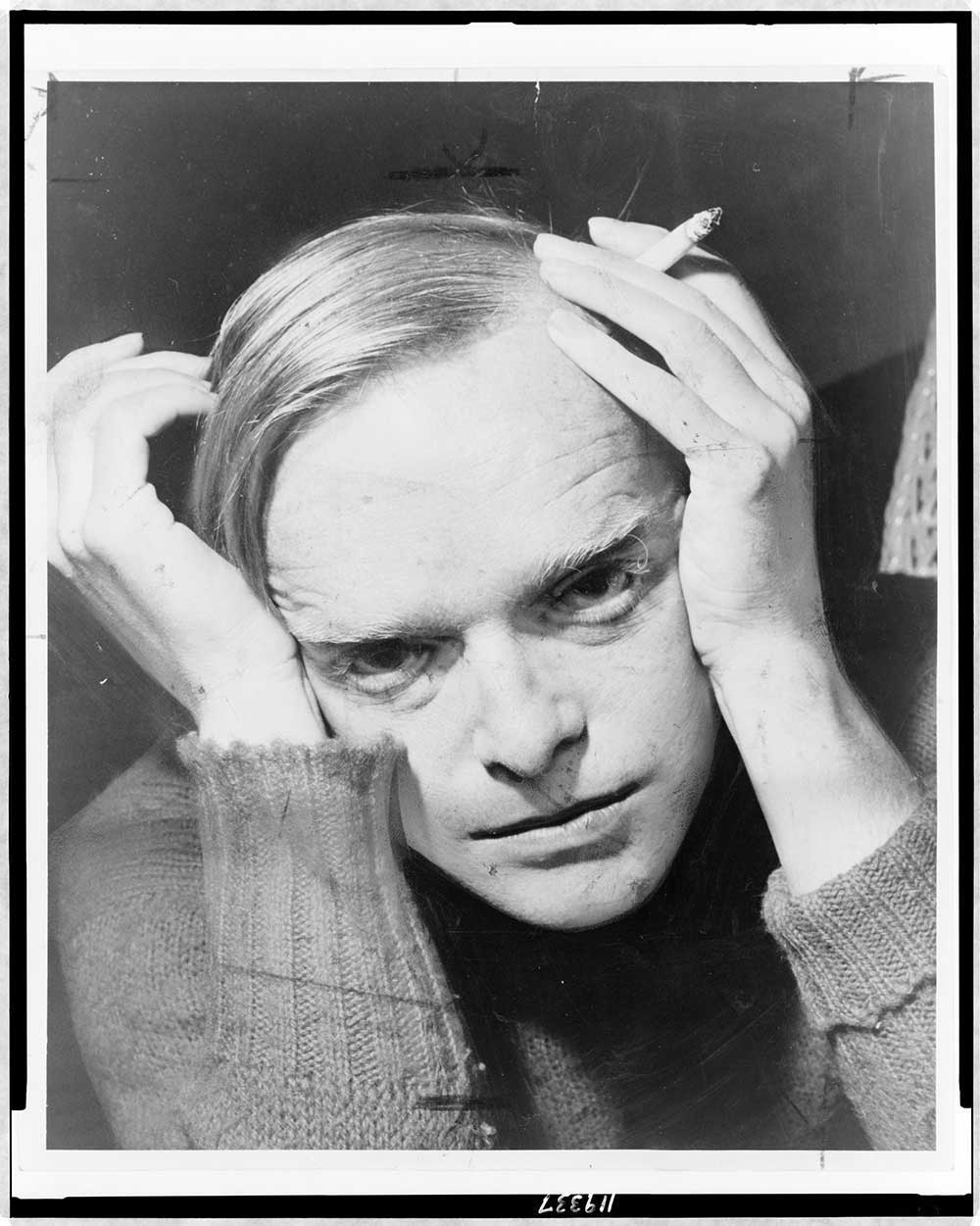

Truman Capote's A Christmas Memory possesses the power to make even contemporary readers summon up their own most-cherished holiday recollections.

- Story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

A couple of decades later the building would be ignited by a careless tailgater’s grill during a football game and burn to the ground. People made jokes about the Student Act being put out of its misery, but I was sad. All I could think about was the fact Truman Capote had read aloud there.

But like a singer singing his own song, pretty soon it became clear that, of course, it was exactly how the words were supposed to sound. And Capote’s almost shocking, lispy soprano was perfect to be the voice of Sook saying, “I made you another kite.”

My love for this Christmas story grows as I get older. It has everything, including a dog that dies; the dog always dies in the end. Now I am more than aware of how hard it is to write in such true rhythm with economy of narrative. I suppose it doesn’t hurt that I spent a year in Monroe County, in the same rural setting Capote described. I cut a Christmas tree in the same native woods, getting lost in the process. “Always, the path unwinds through lemony sun pools and pitch vine tunnels….” Perhaps the best Christmas of my life, or one of the best, was spent in a big house in a bosky oasis inside the Monroeville city limits but as secluded as Mongolia. My first husband and I decorated with fresh greenery and real candles and invited everyone we knew in town to come sing carols. It’s a wonder we didn’t burn down the landmark house, built by a local lawyer and, after his death, inherited by his daughter who had no apparent desire to stay in Monroeville. We didn’t have a cent but were caretakers for the hacienda-style mansion with its fabulous but dry-rotting furnishings. At the old upright piano we sang in our best carol voices, fueled by love and youth and beer and enthusiasm for life. As Bob Seger sang, “wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then.” In truth, the house made me a tad miserable because I knew I’d never own it; even my romantic nature had to come to grips with that. For one thing, the daughter didn’t want to sell it, and, if she had, the asking price for the tile-roofed mansion would have been more than a couple of reporters for a weekly newspaper would see in their lifetimes. But for a short, magical, miserable while we were actors in a play with a grand set, seeing our reflections in borrowed mirrors and hearing the clock strike vanishing hours. That Christmas gathering was one of our best ever, both because of the house and despite it. I’ve never lived anywhere as grand since. It was a cold Alabama winter that followed the giddy December, and the house was too much to heat with its high ceilings and endless rooms. We kept the kitchen and one bedroom warm. One week the water in the toilet bowls froze, and we decided perhaps some practicalities were more important than sun porches, gilded mirrors large as pool tables and 10-foor-tall mahogany secretaries. We moved back to Auburn. What Capote tapped into, of course, is that all of us have a Christmas memory, though few of us can spin them into gold for others. Life has been so good to me, and I am surrounded by friends and enough family and dogs that forgive and forget. I think to have seen the woods that Truman Capote describes and to have smelled and touched its bounty is as close as you can get to writer’s heaven.

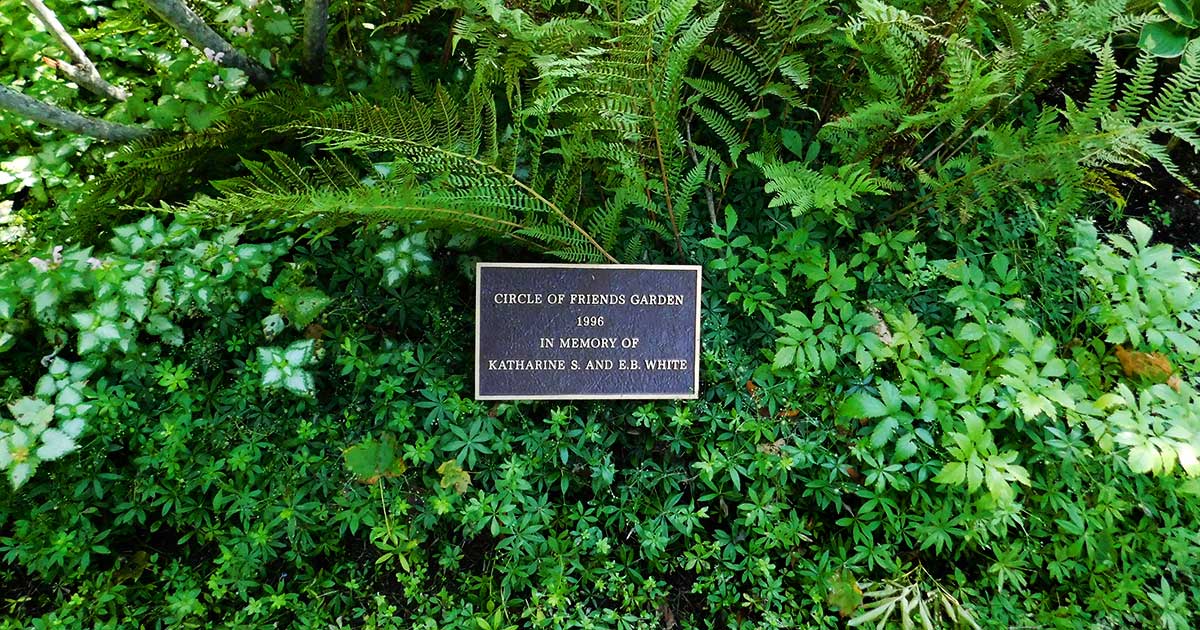

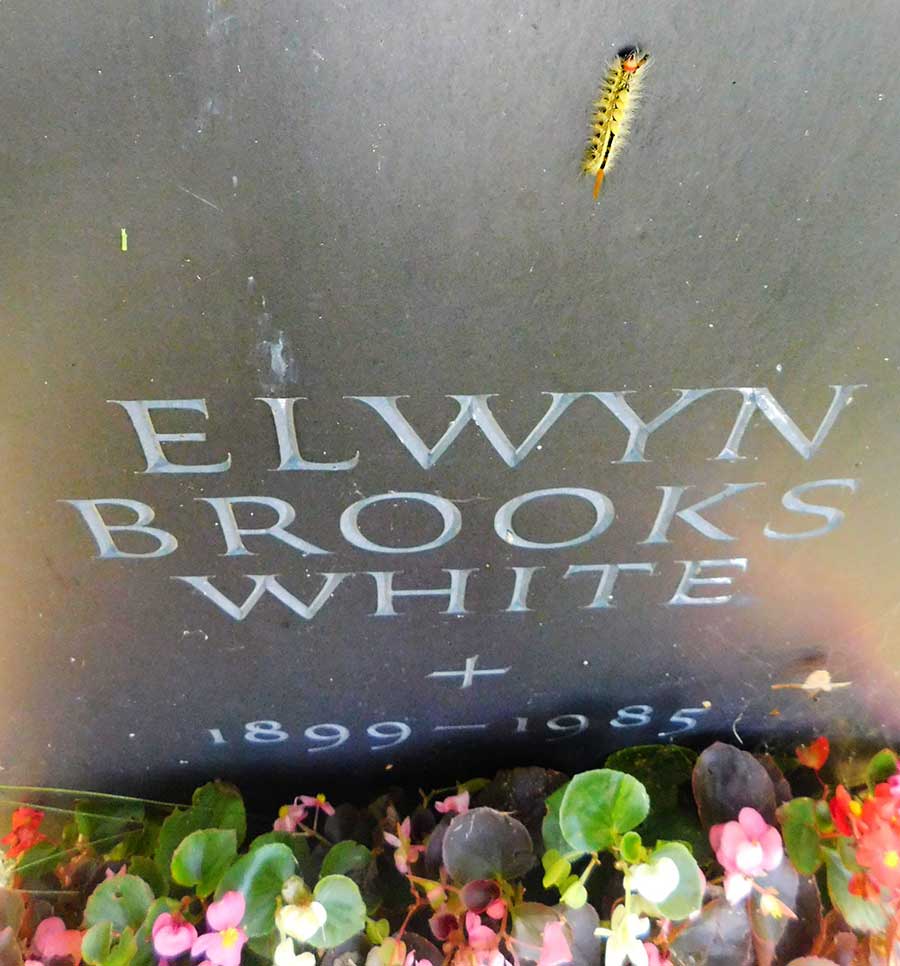

A visit to the Maine home of E.B. White, author of "Charlotte's Web" and "The Elements of Style," two of the most beloved books in the English language.

- Story and photos by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

He wrote in his boat house, hauling a typewriter in a wheelbarrow at day’s beginning and end. A commute, if you will. If you are not sure where to begin a search, go to the library. As is the case in most of Maine’s tailored towns, Friend Memorial Public Library was the loveliest building in the burg of Brooklin. You have to trust a region that values its libraries enough to make them shine. E.B. White is one of my literary heroes. He wrote thousands of well-chosen words for the New Yorker Magazine over five decades. He wrote books for children, including the classic Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little. There are thick collections of his memorable letters. But the book I hold dearest is The Elements of Style, which White co-authored with his former Cornell University professor William Strunk Jr. “No book in shorter space, with fewer words, will help any writer more than this persistent little volume,” The Boston Globe raved upon the publication of the third edition of the perennial bestseller. It is true. Better than grammatical rules reviewed is the “style approach” White made simple. Write with nouns and verbs. Do not overwrite. Avoid fancy words. And so on. It is the bible of spare, understandable writing. If you’ve ever written so much as a letter, you need this book. Beware, however, it will make you a vicious critic of some of the over-wrought writing in vogue these days. Pat Conroy, for instance, would have struggled in Strunk’s class or under a White edit; Donna Tartt would have flunked and fled. I found White’s grave at the back of the big city cemetery simply by figuring he’d take the same approach to death as he had to writing. Keep it simple. There he was – Elwyn Brooks White – beneath a plain Jane marker next to his wife, Katharine Angell, also of New Yorker fame. Name, date of birth, date of death. That’s it. I half expected to see someone’s worn copy of “Elements” on top of the grave, but White’s devotees would never part with their copies. I have the one I bought at Auburn in 1971 and my late husband’s dog-eared copy. The librarian was helpful and pointed out gifts from the Whites. There were two original Garth Williams drawings from the Stuart Little manuscript. The library has a small garden outside named for Katharine and E.B. White, who supported it with both money and hard work. Katharine helped with the garden design. I went to the general store across the street and bought a scone and a t-shirt. I doubt if White hung out there much as he avoided strangers who felt like they knew him. James Thurber wrote White would use the fire escape to get away from The New Yorker office whenever visitors he did not know arrived. “He has avoided the Man in the Reception Room as he has avoided the interviewer, the photographer, the microphone, the rostrum, the literary tea and the Stork Club. His life is his own….” He’s been dead since 1985, but it still felt awkward hunting E.B. White. But I wanted to pay respects, that’s all. So many times he’s saved me from myself. Rather, very, little, pretty – these are the leeches that infest the pond of prose, sucking the blood of words…. That’s the kind of advice that helps a writer, day after day, word after word.

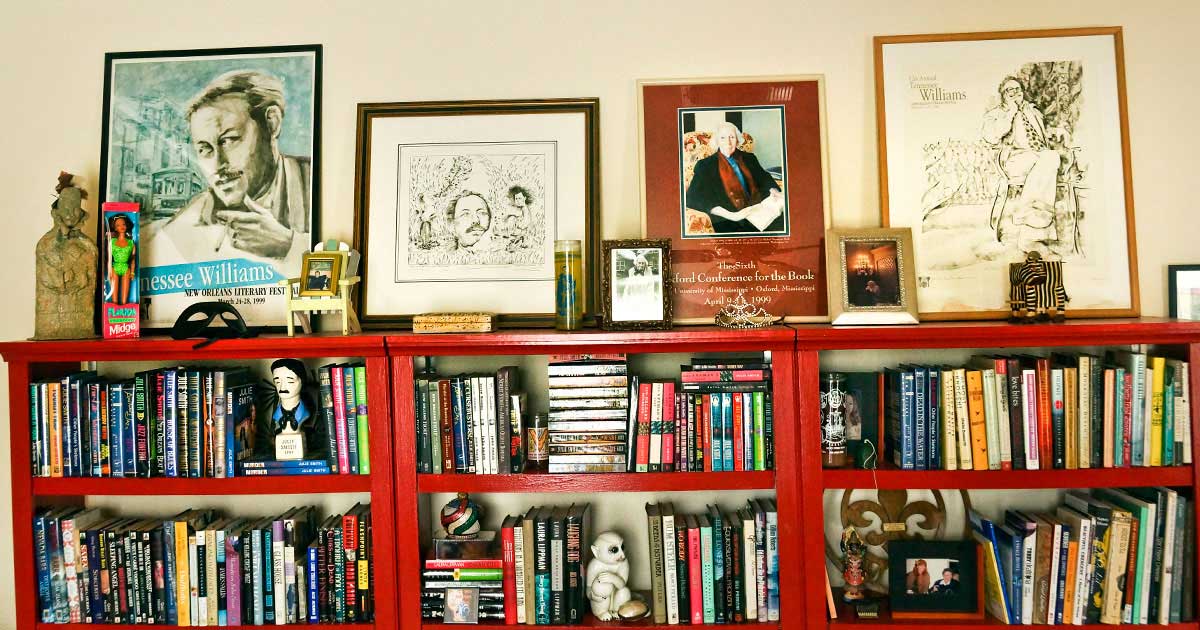

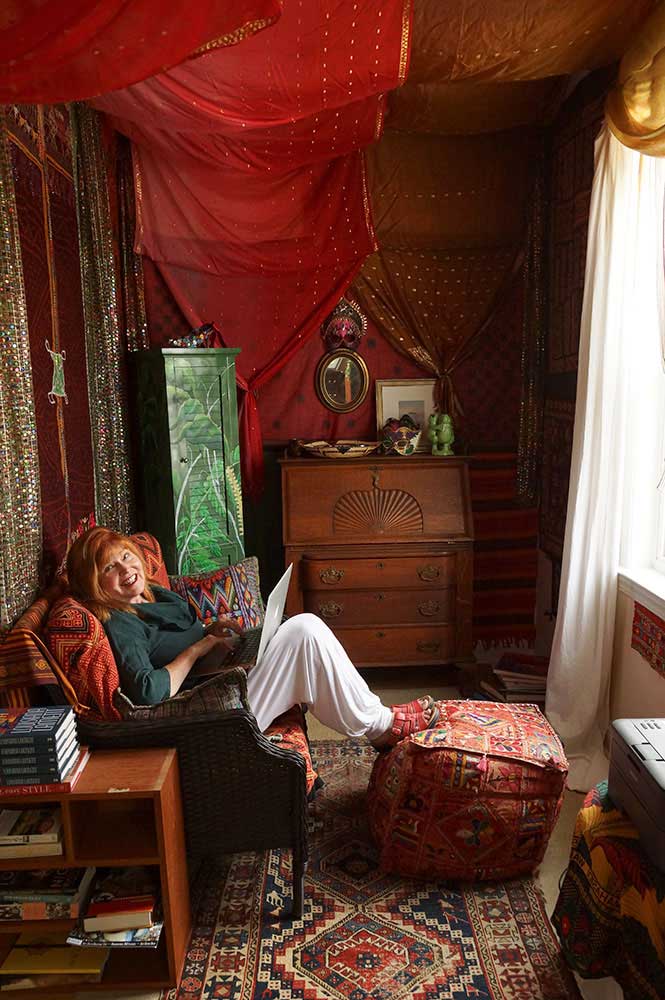

Mystery author Julie Smith sets her detective novels in big cities - but the award-winning writer is embracing the slower pace of living here in Bay St. Louis.

- Story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson, photos by Ellis Anderson

Julie’s 20-plus books have been set in cities, New Orleans and San Francisco, so it is hard to imagine Julie living in a small, seaside, tree-canopied town with plenty of parking and little crime. But imagine again.

A few of Julie Smith's books

|

|

|

Across the Bridge - July 2019

|

Artist Cindy Easterling creates kiln glass works that reflect the beauty of life on the Gulf Coast.

- Story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson, photos by Rheta Grimsley Johnson and Cindy Easterling

She will be one of the featured artists at the upcoming exhibit “Water, Water” at the Walter Anderson Museum in Ocean Springs.

Her website is www.passbeachhouse.com.

|

She is a slip of a woman with eyes big and bright as a child in a Margaret Keane painting.

Cindy Easterling, architect and fused glass artist, has more energy than the proverbial law allows and a sense of humor about life and its many curve balls. Hurricane Katrina demolished much of the condo complex, including stairs, which her absent sister had just purchased as an investment in August of 2005. So, Cindy asked friends to hold the extension ladder while she climbed up to the third floor to see what was salvageable. “I looked like a turtle, climbing back down with a laundry basket strapped to my back.” |

Across the Bridge

is sponsored by |

The motion of the ocean is reflected in the glass that has become Cindy’s passion, an art she perfects in a shed where kiln space is divided with rakes and shovels. The shed/studio is behind her old pink house near the beach in Pass Christian. The house looks like a beach house should, not some brick McMansion but a wooden relic that has withstood a lot and earned its defects.

“That’s why I chose it,” she says.

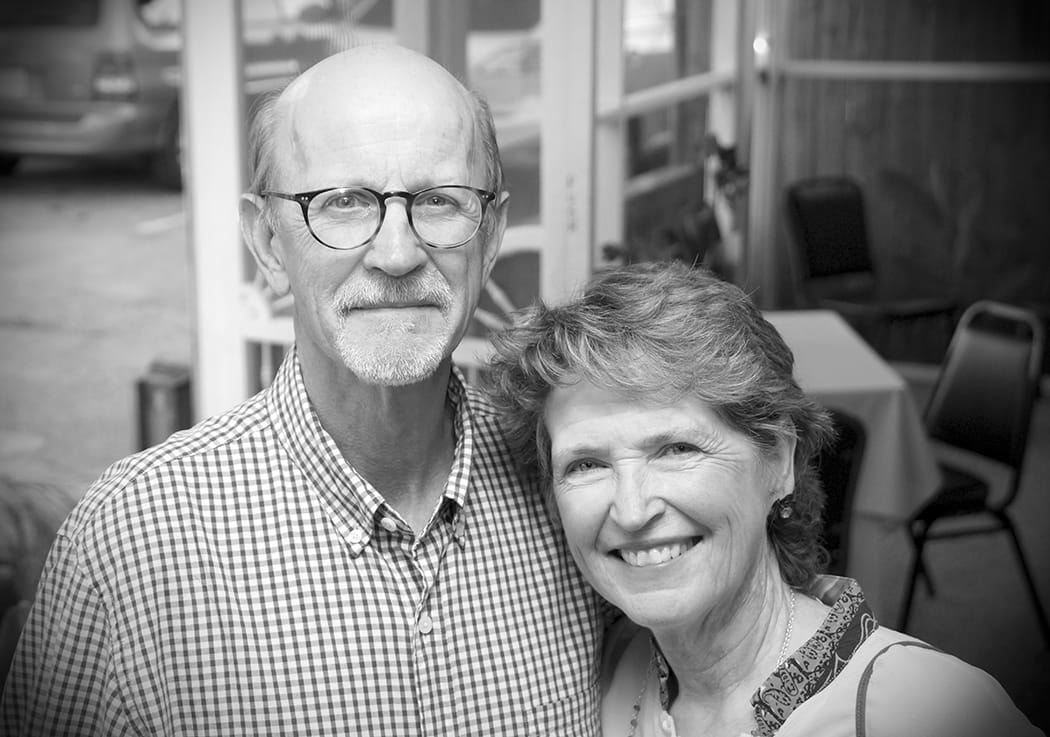

Her grandfather’s house in the Pass, where Cindy spent many happy childhood days, was heavily damaged in Camille, and her great-grandfather’s house destroyed. But that did not dampen her enthusiasm for the coast. Buying an old house in the same town appealed to both Cindy and her engineer husband, Bob, who loves to sail.

But right now they divide their time between the Pass and St. Louis, where her architecture business and Bob’s job and elderly mother keep them anchored. They hope someday to live full-time on the coast, and they plan their lives around that eventuality.

Cindy’s work has become increasingly popular all over the coast, and its distinctive transluscence and sea glass colors make it instantly identifiable. Some would say recognizable work is the mark of genius, like a Willie Nelson upbeat riff, or a Walter Anderson swirl.

Her fused glass work, also called kiln glass, began about seven years ago when she took classes from a neighbor at Craft Alliance Gallery in St. Louis.

“But it all really began in college with a bottle cutter,” she insists. That bottle cutter stayed on a shelf for more than 30 years until an empty nest and self-employment -- after years in the corporate rat race -- let her pursue her art again.

A New Orleans native, Cindy graduated from Newcomb College of Tulane University. She was in a fine arts curriculum but her father insisted that her degree must be in something “practical” enough to support herself, need be, so she finished in architecture as a kind of compromise.

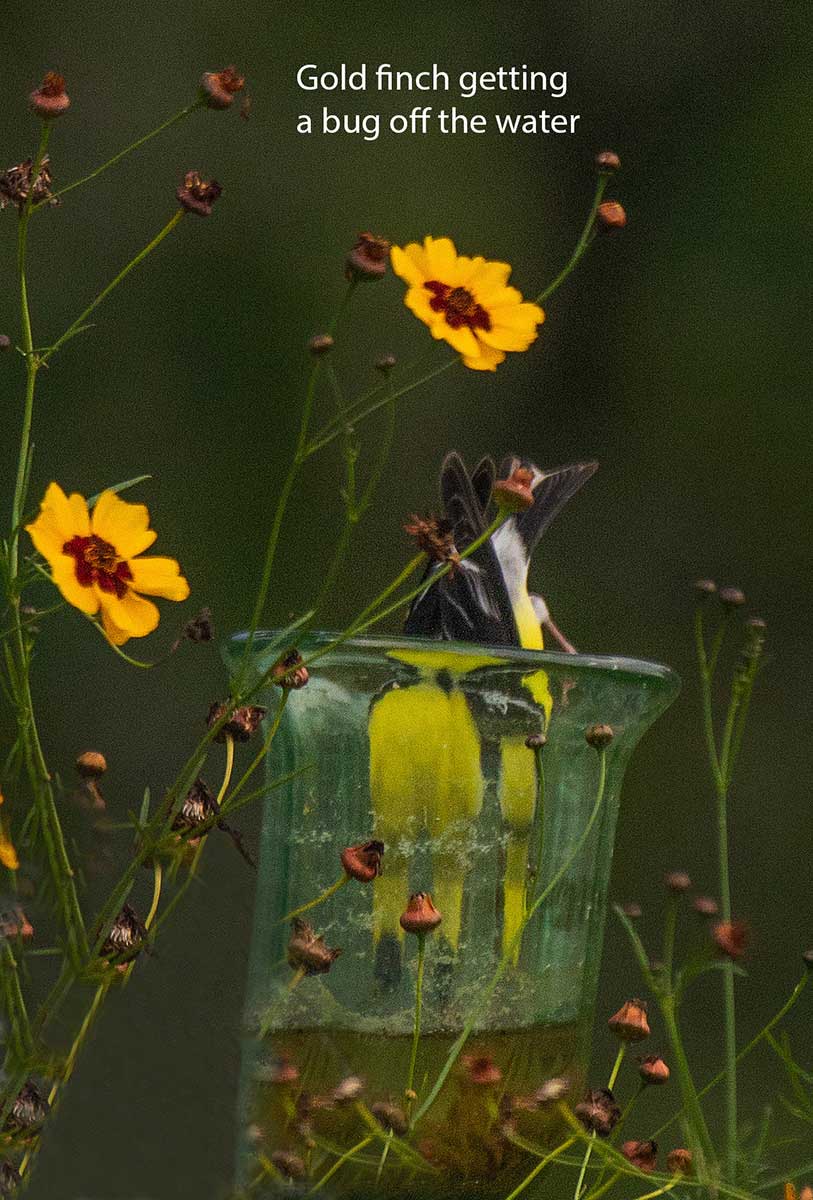

Now, with time and the Mississippi Gulf as inspiration, she makes plates, vases, dishes, platters, ornaments and other glass delectibles, using American or recycled glass. They are both functional and decorative, but all beautiful. “I love the play and interaction of light on glass.”

She likes to be able to see through the pieces, so usually at least two layers of flat glass are cut and fused together at high temperatures to add strength. Decorative flourishes can be more glass – descriptively called stringers, frits and confetti – or gold, silver, copper or other metals.

“The first thing that I do every morning is open my blinds and look out at the water, trees and clouds. It is different every day, and I never get tired of looking at the view.”

Her house designs through the years also spawned another hobby. Cindy hopes to compile a book of photographs she made of homes in the Pass before Katrina, which now can be found on her note cards.

Those photographs, she says, “are an outgrowth of looking through the lens at details” and different views of the homes she designed and the old homes she loves.

It pleases Cindy no end when her art projects find “a good home,” and other people see in her work the ocean, the sand and the vegetation of the area she loves.

|

|

Across the Bridge - April 2019

|

- story by Rheta Grimsley

|

Buried beneath layers of duty, I found a tasty scrap of time to listen to good music. Getting older so far hasn’t meant more idle hours for what I love the most – playing old songs at top volume. With age should come that privilege. Every now and again I just say “no” to 96 choices of cable television shows and unlimited movies and emails stacked like cord wood. I have to hear my music, and by “my” I mean songs that have delighted, teased, moved, sustained and tormented me. The good stuff. |

Across the Bridge

is sponsored by |

I filled my glass, put my feet on the leather ottoman bought on the cheap 30 years ago at a Jackson department store, and mentally strapped down for serious time travel. The shuffle feature made the trip more kaleidoscopic than chronological.

Bob Dylan, for instance, carried me ‘way back to Loachapoka, Ala., where oddball friends often gathered on old bedspreads in tall grass to solve the world’s problems. My back pages are in braille, a stubble of memory and meaning that feel good to touch.

Aretha took me to a dorm room in Auburn where a steam radiator hissed and, without irony, we sang “Natural Woman” while wearing electric rollers in our hair and cold cream on our unlined faces. Collegiate independence came with a safety net – “I’ve overdrawn my checking account, Daddy, and I don’t know how it happened.” – a sweet spot in life.

The inimitable John Prine put me on the pristine banks of the Middle Fork of the Salmon River on an early June raft trip. We weekend adventurers ended each night around a campfire listening to Prine’s soft picking and the recitation of Robert Service poetry.

Before that trip, I didn’t know anything about either Prine or Service, two poets you discover you need while negotiating what Lewis and Clark called The River of No Return. Try bookending Prine’s “Souvenirs” and Service’s “Yellow” and your boat will float.

Music is lightning. Every listen might just bring to your life something you didn’t know you couldn’t live without.

Speaking of rivers, Emmylou and Mark Knopfler sang Hank’s “Lost on the River” and reminded me that I come by my passion for music honestly. My father played Hank again and again on the first piece of furniture he ever bought: a Crosley record player, one with a lid that had to be cleared of Mother’s knickknacks to use.

Hank has been to my life what calcium is to women; you need more and more Hank the older you get.

I was enjoying myself immensely, feeling better and wiser with each selection, when suddenly Patty Griffin weighed in with her “Mother of God” song. “I live too many miles from the ocean,” she sang, “and I’m getting older and odd….”

I’m definitely getting older and odd, but thank goodness the first part of that lament doesn’t apply to me any more. I no longer live too many miles from the ocean.

Each time I go to the grocery or the bank I make a point to get at least a glimpse of the Gulf, the reason I’m here, the reason almost all of us are here.

I try to remember what a great gift it is to live on the edge of the sea, whence we came. Life and politics and aging may make us blue, bring us down, and send us running to the stereo and our most dependable old tunes.

But as long as I have what Jimmy Buffett called “Mother, Mother Ocean” a few steps away, there should be a smile buried somewhere in my wrinkles and a song in my flinty heart.

Read more about award-winning author Rheta Grimsley Johnson on her website - you'll also be able to order her books!

|

|

Across the Bridge - January 2019

|

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

At noon on January 31 she will speak to a joint meeting of Gulfport’s Kiwanis and Rotary clubs.

|

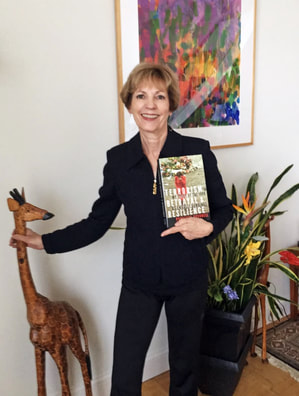

Prudence Bushnell looks like her name sounds. Neat, petite, well-dressed and well-groomed. Like a resounding success of a 1950’s upbringing, when Captain Kangaroo woke us up and our mothers put us to bed.

Friends, and I am one, call her Pru, which somehow changes everything. Pru has a wicked wit, the resume of a Bond girl and an intellectual curiosity that gets her into more jams than Nancy Drew. She is tough. |

Across the Bridge

|

|

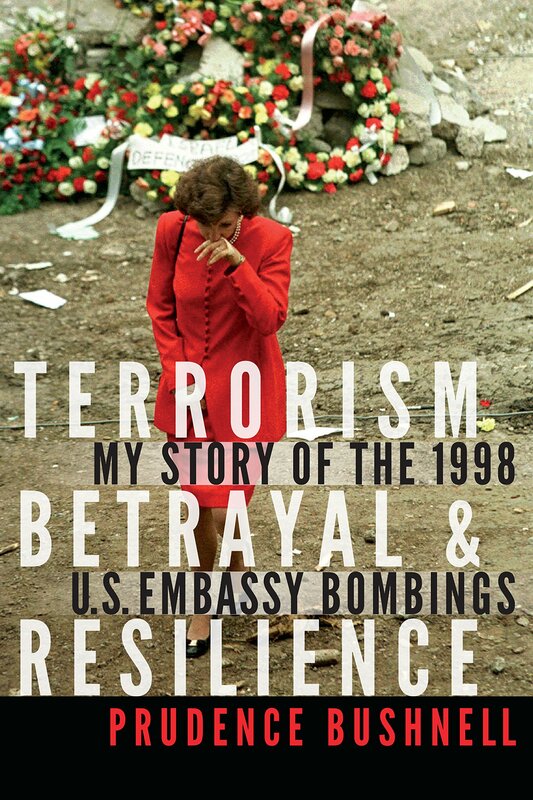

Her book – Terrorism, Betrayal & Resilience – is amazingly relevant to today’s world, and proof that often the dust must settle before you can see clearly the truth.

“The building swayed; a teacup began rattling; shards of glass and ceiling tile sprayed the area,” the book begins. “One thought swirled dreamily around my brain as every muscle in my body clenched in revolt. ‘I am going to die….’” |

And in telling that story from a hard-hitting, non-partisan perspective, she illuminates flawed characters, policies and agencies.

For it isn’t always a flattering portrayal of the national security community or politicians. Her exchanges with Susan Rice, Madeleine Albright, Bill Clinton and other “name” public servants sometimes make you wince. This is a minefield of what-ifs.

Pru grew up in exotic places and largely patriarchal cultures, everywhere from Paris to Pakistan. Her father was in the foreign service, her mother the perfect foreign service wife, not an easy job that included, in post-war Germany, hosting orphans and helping widows.

“As a girl growing up in the 1950s, it was inconceivable that I could become a leader, much less one who excelled in disasters,” Pru writes.

“My only role model was Joan of Arc, and I was well aware of what happened to her when she put on a pair of pants and led men.”

So it surprises no one more than Pru what a continuous adventure her life has been, a serial of true and turbulent stories that make a mockery of Hollywood and its “Homeland”-style heroines. From her first assignment in Dakar, Senegal, she has worn the pants and embraced the leadership role fate assigned her.

“We were doing nothing to stop the killing, so I took it upon myself to call Rwandan military figures perpetrating the genocide to let them know we were watching and to advise that they would be held personally accountable for their deeds,” she writes.

That episode of her life would be depicted in a movie, “Sometimes in April,” in which Pru is played by actress Debra Winger.

The cover of her new book – Pru is walking away after laying a wreath at the bomb site in Nairobi – is a photograph by John McConnico that won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Photojournalism.

From Kenya, still suffering with post traumatic stress, Pru became ambassador to Guatemala, hardly a healing place. There she was burned in effigy and watched, from a distance, as the United States was attacked by al-Qadea on September 11, 2001.

This visit to the Pass is due to her friendship with former State Department employee and Pass resident Betty Sparkman.

The book, published late last year by Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, is on sale now at Pass Books.

|

|

Across the Bridge - Dec/Jan 2019

|

|

My home in the Pass is a what’s-wrong-with-this-picture Alpine chalet, with a steep roof capable of quickly shedding 20 feet of snow should South Mississippi ever get that much.

In a town of melon-colored beach cottages with palm trees and sun-loving perennials, my strange house doesn’t belong. Even the trees in its shady yard are all wrong, a plethora of hickories rare to the region. |

Across the Bridge

|

My house looks its best at Christmas. With a live tree in one of the big glass windows that fill the front, it is if the outside has slipped inside, blurring the lines between exterior and interior convincingly. Only unraked hickory leaves banked against glass reveal the demarcation.

The Christmas tree is up, no credit due me. Two nice young men from an Ocean Springs nursery set all eight flocked feet of it in its ready-made stand in the proper spot. They left. And now the tree looms unlit and bare and dares me to decorate. So far I’ve avoided it.

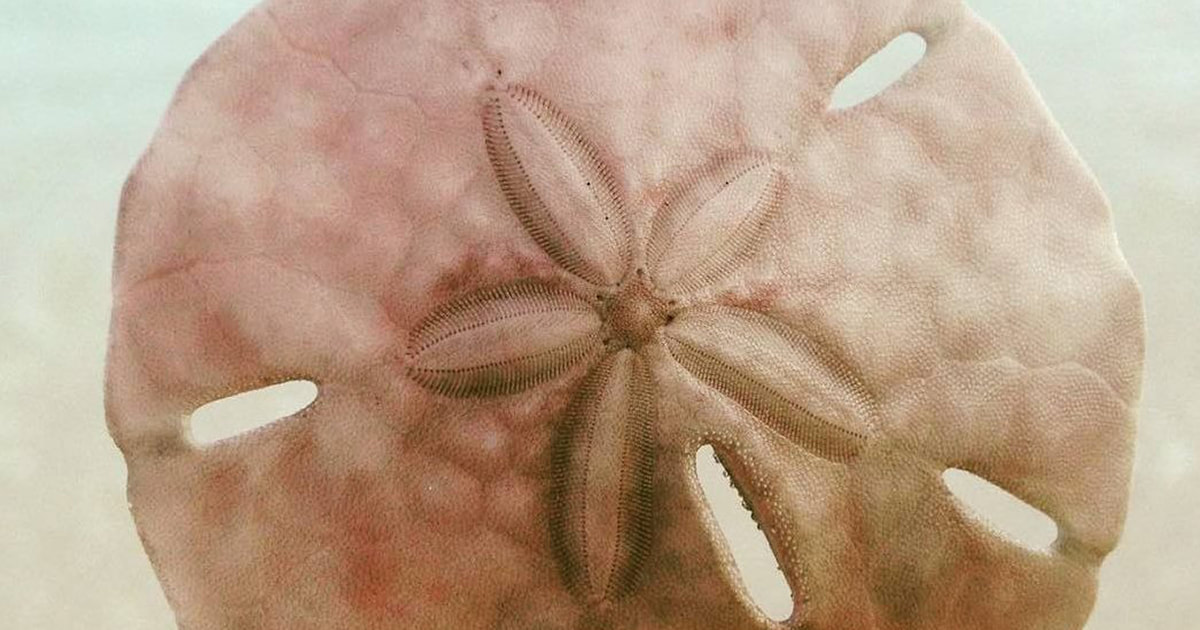

Somewhere in a laundry room that also serves as my office and domestic catch-all is a box of sand dollars I often use as ornaments. I picked them up on a St. Simons Island beach 43 years ago – Georgia, again -- bleached them white and strung ribbon through the holes nature gave them. Whenever they are touched, ancient sand still falls out.

I realize that means the sea urchins were not dead when I harvested. The dollars that were dead or dying – “moribund” Wikipedia calls them – would have been on the beach being naturally bleached by the sun. My catches still had their velvety silica and were moving in concert and about their business, possibly even cloning, when my toes touched them.

Maybe that’s why they make such ideal Christmas ornaments. They come packaged with their own guilt, which powders the floor as I hang them.

And I will get around to hanging them. I always do. Else those urchins in the order Clypeasteroida would have died in vain.

Only a couple of times have I gone another decorating route. One recent year the tree was artificial and pre-lit, a gorgeous specimen I “won” at the Hancock Library tree gala, homage to those innocents killed in Paris by terrorists, and decorated with French flags and Eiffel Towers.

Something must jumpstart me into the season, reminding me to get through it. Probably it will be music. Usually is. The “Blood Oranges in the Snow” album Carole McKellar gave me one year is good for a nudge. That’s by musicians called Over the Rhine, a husband and wife duo that do the best cover of “If We Make it Through December” I’ve ever heard.

And there’s the holiday blues collection my New Orleans buddy John Bedford gave me as a gift one year. Till you’ve heard Charles Brown’s “Please Come Home for Christmas” three or four times nothing gets done.

You can run from the holidays, of course, but you cannot hide. For one thing, it’s hard to avoid the sight of an eight-foot tree covered in artificial snow in a small living room two blocks from the beach. Emotional blinders only hide so much.

By the time you read this I’ll have found the box, hung the sea dollars, played the albums, had a good cry and gone on about my holiday business. If I remember to water it, this monster tree might even serve for Mardi Gras. Or not. I’m usually first to the curb with leftovers.

The melancholy is as much a part of the season as tinsel and wassail. It passes.

And soon enough, the tree can be on the beach, fueling a bonfire, toasting the very toes that tentatively outlined the urchins that, with any luck, will go back in a shoebox and make the clutter cut for another 43 years.

|

|

Across the Bridge - Oct/Nov 2018

|

|

For decades, in print and cocktail prattle, I’ve touted the Mississippi Coast as the best place on earth for festivals.

From Oyster Eve in the Pass to Dolly Should in the Bay, nobody does it better or more frequently. Even if you forgot all about Mardi Gras – and who would? - the Gulf Coast culture is sewn up with gossamer get-down, get-together thread. And I still say we should win some kind of national title for hosting elaborate shindigs at the start of a season or drop of a hat. |

Across the Bridge

|

I recently visited relatives in the town of 4,800 just after grape harvest. Freinsheim is at the center of seven wine-making villages. How’s that for convenient geography? So it’s a big deal when the grapes are picked and the new crop sampled.

Let me tell you about the party.

One Saturday afternoon on cue thousands of people wound their way through the endless grape vineyards and walked for miles into the sunset. But this was no sweaty, non-stop marathon in the name of exercise. Oh, no.

We had only just entered the orchard when appeared the first kiosk selling tall glasses of new wine. The glasses were dimpled, the better to hold them, and the general idea was to throw back refreshment as you made your way forward to the next wine filling station.

Thus refreshed, we tramped on for another few hundred yards and then did it all again. You could sip or chugalug, didn’t matter. You knew where your next drink was coming from.

Not everyone walked the entire course. Some cheated. A few families set up picnic tables between the vineyard rows and ate and drank at their leisure. Some lounged on cushioned chairs provided, I suppose, by the various wineries.

I kept walking and drinking, which is a lot easier than you might imagine. The new wine had about a six percent alcohol content, roughly a beer’s worth. I’ve done the same thing getting to the far end of Ship Island while lugging a cooler.

The most amazing thing was that nobody in the wine-swilling crowd of thousands appeared drunk. There were no fistfights or loud words. The only music was the occasional accordion, yet it seemed as if our lubed conversation was orchestrated.

As the sun got lower and the crowd higher, I kept waiting for the down side of such a frolic, a sick teenager, passed out geriatric or an angry boyfriend. It never came. Now I didn’t stay into the wee hours and the scene might have changed, but somehow I doubt it.

Theirs is an old and grape-fueled civilization.

Almost before I knew it, my group had reached a vineyard hilltop that looked down on the red-roofed medieval village of Freinsheim. We rested. And drank some more.

We didn’t so much walk as float home. I kept thinking wistfully of a similar production along the edge of the Mississippi Sound, but I don’t think it would translate.

|

|

Across the Bridge - August/Sept. 2018

|

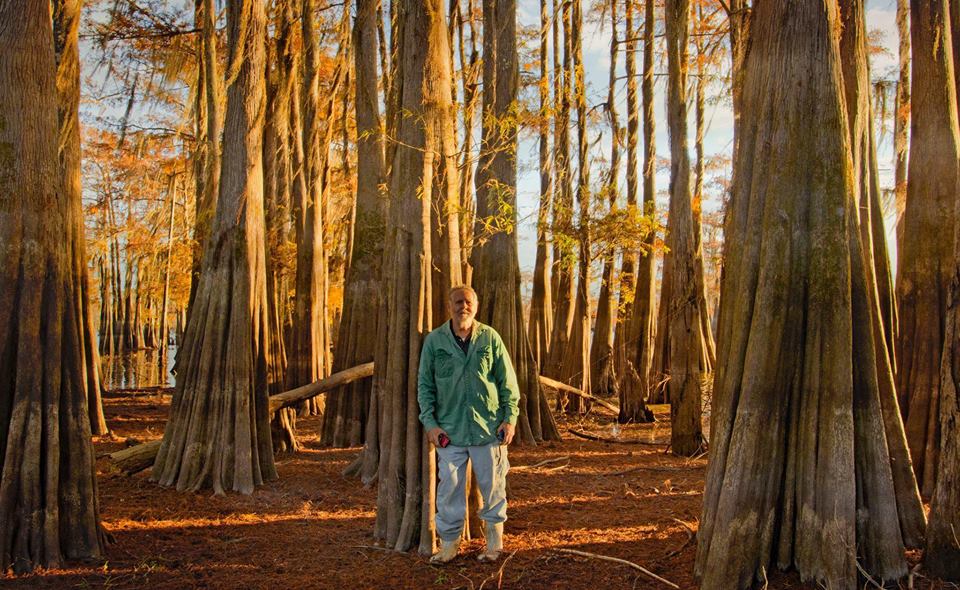

- story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson, photography by Marc Lamkin

|

I have a photographer friend in North Carolina who grew up in Louisiana. You can take the boy out of the pea soup humidity, but you can’t take the dread of it out of the boy.

When I’m on the coast and we email, Marc constantly asks about the local temperature. This year, in May, he referred to the Gulf Coast weather as “early brutal.” That’s about as apt as you can get. He sits on a beautiful mountaintop in North Carolina and worries about us. He probably swats at imaginary gnats. The reason I mention Marc is because recently I closed the little art gallery I attempted to get going in North Mississippi. Not enough interest. Read that, no interest. |

Across the Bridge

|

Marc seems to be sincerely feeling my pain about the closing. Few do.

I mailed back his unsold photographs that combine humor, pathos and beauty in the strangest, most delightful way. I felt like a fool. How had I failed to sell those?

An architectural photographer by trade, Marc still shoots a couple of “official” jobs each year, but mostly now sits on his deck and lets the subject matter come to him. He shares a lot of pictures of sunsets, flowers, grandbabies and rainbows. They are beautiful. I find them infinitely more interesting than 99 percent of the art photos I’ve seen in coffee table books and museums.

And yet Marc admits to missing real deadlines and relentless struggle to get a job done just right. But probably not enough to leave his comfortable perch and his big loving family and take to the road again.

I used to think nothing of writing four columns a week. Now I struggle to write one essay every other month.

My idea with the gallery was to exploit the artists and other creative folk I’d met in four decades of trolling for columns. I would have art receptions, book-signings, music events and cartoon exhibitions. I would do all of this in a town of 3,000 that has six auto part stores, 12 beauty salons, 22 churches and not much else.

The work would be different, more social than sitting at a computer by myself for hours each day while attempting to turn a phrase. I was good at my job, but I was tired of it, too.

The things I worried about seem silly now. I worried about having enough inventory, and now struggle to return much of it. I worried I didn’t know enough about art to start a gallery. Turns out, I knew far too little about business to start a gallery.

Right out of college I tried to birth a weekly newspaper. After 26 weeks, the adventure was over. I swore to myself then that I’d never be in business for myself again. Until two years ago, I remembered the lesson.

Marc says I get points for trying. He charitably called me a “risk-taker,” which is a nice way of saying I threw a lot of money at a vision nobody could see but me.

We remember our old jobs – the hard work and daily deadlines, bad food, bad roads and lonely nights -- the way Marc remembers the dreaded humidity. At the core of our beings.

And, still, we miss it.

|

|

Across the Bridge - June/July 2018

|

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

|

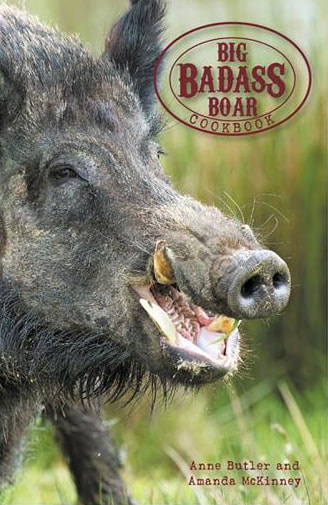

Wild boars have always been good to me.

It was an Atlanta newspaper assignment to cover a wild boar hunt in Louisiana that led me to buy a houseboat on the Atchafalaya, which led me to spend 14 years of my life exploring the most exotic and regionally distinctive part of these United States, which led to my book Poor Man’s Provence, which, as Hank would say, has bought me a lot of bacon. That original story – wild boar hunt as bachelor party – wasn’t much, but at least I got the idea of how flat-out ugly a 200-pound pig with tusks can be. Didn’t make my mouth water. Now my prolific writer friend Anne Butler of Butler-Greenwood Plantation in St. Francisville, La., has her name on the cover of yet another book: Big Badass Boar Cookbook. |

Across the Bridge

|

Recently her home was the setting for a Hallmark Channel movie, one of those romance stories that has scenery so beautiful you don’t mind the show is missing good acting and a plot.

This time out my author friend is wearing her good citizen hat, helping to tackle what’s become a real problem in the woods of Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana and, yes, her own lush but manicured backyard.

The Big Badass Boar Cookbook, co-authored by Amanda McKinney, reports that wild pigs are more destructive than nutria and may be “the most prolific large mammal on the face of the earth.” Feral hogs average six piglets per litter and can have several litters per year.

“When prepared properly so that high temperatures destroy any internal bacteria, they are safe, tasty and cheap.”

Being a responsible sort, Anne includes in her book a list of diseases that humans and hunting dogs can get while cleaning, butchering, handling or eating wild pigs. It sounds a little like the inevitable side effects list whispered quickly at the end of television ads for pharmaceuticals.

Swine brucellosis, leptospirosis, trichinosis, toxoplasmosis tularemia and swine influenza are reasons, for instance, that the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries no longer provides any recipes for cooking your wild boar kill.

This cookbook, however, gets past the warnings about safe butchery and cooking to share both high- and low-church recipes. Famous Chef John Folse is included. So is John “JD” Desselle with his “Wild Hog Street Tacos” and Kerry Bordelon with “Real Hog Headcheese.”

I haven’t been offered any of the 180,000 pigs killed in Louisiana per year, or from anywhere else, so I probably won’t be using the recipes, though I love game and love to eat and try to keep an open mind when it comes to food. I’d sure try a hog if I knew the source – and the cook. The taco especially sounded good.

The cookbook mentions nutria and how Louisiana chefs also concocted recipes for those rats. It took pseudo-sophisticated New Yorkers to belly up, however, and then only after menu writers got creative and used the French for nutria -- ragondin -- and made the rat sound better than it tasted.

I never tried it; I owe nutria nothing.

Once, in Leland, Miss., city hall tried to solve a beaver problem in the town’s picturesque Deer Creek by introducing alligators. You can guess how that story ended.

I call it The Kudzu Syndrome. The story often ends badly when something is plopped into an environment not its own. Anne’s book says Spanish explorers brought us the wild boars. My alma mater Auburn, or at least its extension service, gets the blame for kudzu. Louisiana fur farmers for nutria.

The moral of this story? Look before you leap. Cook before you eat. One man’s beast is another man’s pate. A wild boar in the pot is worth two in the bush.

Stop me before I hurt myself.

|

|

Across the Bridge - April/May 2018 |

- by Rheta Grimsley Johnson

|

My dog Boozoo is named for the late Zydeco king, Boozoo Chavis, though, honestly, I know little about the man or his music. Authorities say his accordion squeezed into existence modern Zydeco.

Chavis died only a few days after I adopted a year-old Boo from the pound, 17 years ago this month. I was staying in Henderson, La., and the French radio station was all about Boozoo, all the time. “What a great name,” I thought. The Lobo song about “me and you and a dog named Boo” ran through my head as well. Names are important. Children suffer mightily from cute attempts at naming by careless parents. I myself am a victim of bastardized spelling. |

Across the Bridge

|

I always try to envision yelling a dog’s prospective name loud and long into a populated world without sounding foolish. I try to keep it simple.

Boo was the perfect name for a perfect piebald, brown and white, mixed-breed. I’ll admit. I first wanted him just to release some of the pressure cooker steam that powered my young yellow Lab, Mabel. I wanted another energetic puppy to run her ragged.

Boo did that and more. He was devoted and diligent, even after he caught a slow-moving pickup truck that broke his leg. It was set but never mended properly. That didn’t slow him much, not for a decade and a half anyhow.

Boo was born to play toady. He didn’t seem to mind leftover collars and leashes and bowls. He took whatever bed that was left, possibly remembering the hard ground from his year in the joint. As long as he got enough food, he was uncomplaining, even happy.

Life without him is hard to imagine.

But on a recent Sunday I had to start. Imagining. Life without Boozoo. Friends took turns digging a grave for him across the branch in the hollow in North Mississippi where I spend much of my life.

Boozoo had fallen, reinjuring that old break in his front leg. He’d essentially been a three-legged dog for all these years, but now he was down to his two back ones, those stiff and straight from arthritis. Any attempt to walk sent him crashing on his head, or sometimes his side. When that happened, he thrashed about frantically like a beached fish and yelped.

The plan was to take him to his veterinarian on Monday, soon as she opened, let her inject a little mercy and bring his tired carcass home. Plans are for fools.

The doctor couldn’t see us till 2 p.m. I was glad for the extra time. I spent most of that day lifting Boo to wherever he needed to be, and then watching him sleep a fitful sleep. Because he’s always been about the feed bowl, I gave him extra and special rations.

I gave Boo Vienna sausages. I knew from experience – countless fishing expeditions as a child – what a guilty pleasure those could be.

I left a little early for the vet’s office to drive a way we never go. My thought was that by using a different route Boo wouldn’t suspect our destination.

I went inside and told Boo’s doctor what was happening and asked if she’d bring her needle to the car. She pressed me to allow an examination.

I rather reluctantly brought Boo to her table, resenting the trauma that he always feels when boosted onto the slick exam table. Not a good last memory, I thought. Better to have ended with Vienna sausages.

“It’s not broken,” she said. “We could try an anti-inflammatory and if it’s going to help it will help quickly.”

That is how Boo and I soon were on our way back to the hollow, adjusting to a new routine. The shot made a dramatic difference. The pain seemed to go away. He still stumbles but less frequently.

Boo for the first time is the center of attention. The other dogs sense he’s been promoted.

And I am walking that fine line, doing a little stumbling myself. It is hard to decide when to let go. On the one hand, it’s easy to do all you can for an old, old friend who has never made many demands before. But I don’t want to make Boozoo – veteran of The Joint – suffer needlessly.

For now, at his doctor’s suggestion, we soldier on. “It won’t be for long,” she said.

Boo has been through all the states between Mississippi and Colorado. He has visited in Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia and Tennessee. He’s been in the back of a half dozen vehicles and on the cover of a book. He’s growled at one person, nipped one person, fought occasionally over food, but mostly been a sweet-tempered, long-suffering, patient-to-a-fault companion.

The pile of dirt across the branch is a constant reminder of Boozoo’s ultimate destination. Pulling back from it, if only for a few days, feels right.

|

|

Across the Bridge - Feb/March 2018

|

|

We were a Huntley-Brinkley family. The same way most American families in the 1960s swore by either Fords or Chevrolets, television viewers chose between Walter Cronkite or NBC’s The Huntley-Brinkley Report for their news.

I’m not sure of the rationale for my father’s choice, and it was his choice, because the adults decreed programming. I still can feel the round, corrugated knob that changed channels on our black and white set, though I only did the honors occasionally, as on Sunday night when I knew we’d be watching “Bonanza.” We trusted Huntley-Brinkley, a no-nonsense duet of hard news, the memory of which makes it impossible for me to like the silly patter that passes for television news these days. And, of course, we got the local newspaper, as essential in every household back then as the calcium in milk for bone growth and tooth-brushing for general hygiene. We read it. Cover to cover. |

Across the Bridge

|

Not to disparage today’s working press – enough unfounded criticism twiddled and Tweeted lately – but I miss the staccato rhythm of the old-fashioned newsroom and the disposition of old school reporters. They never expected to be liked, for one thing, which is probably why they sometimes were idolized.

Two things happened recently to satisfy my nostalgic longings for solid, shoe leather journalism out of the Damon Runyon mists. One was the movie “The Post,” which celebrated the guts it took for The Washington Post to publish the Pentagon Papers.

I went to the movie not expecting to like Tom Hanks as Ben Bradlee, though I like Tom Hanks. I simply didn’t think he could reach the gravitas bar that Jason Robards set so high in “All the President’s Men.” But Hanks did. He exhibited the sardonic wit and passion for truth that characterizes the best in the trade. If your mother says she loves you, check it out.

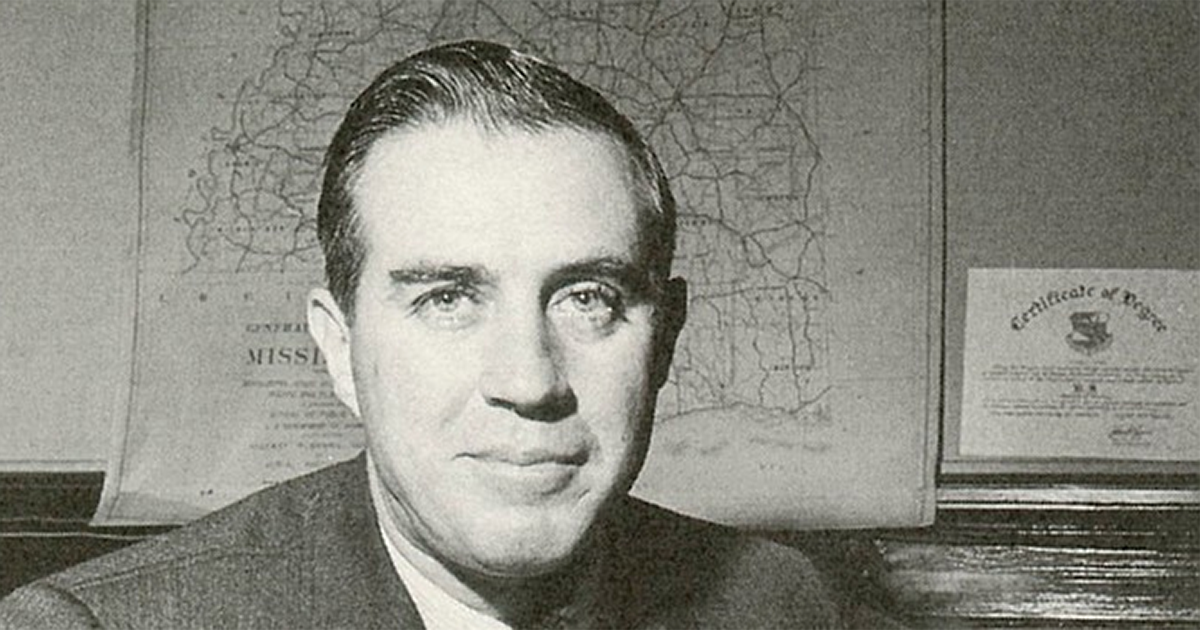

The second surprise was local, a documentary screening in the Pass Christian library of

“Bill Minor, Eyes on Mississippi; The most essential reporter the nation has never heard of.”

The room was full. In the film the late, great reporter Bill Minor pretty much narrates his own story, drawn out by the questions of Ellen Ann Fentress, producer and director. Ellen Ann was hired by Bill when for several years he ran a liberal alternative weekly in Jackson, The Capitol Reporter.

In all, Louisiana native Bill Minor wrote from Mississippi for 70 years, beginning with Theodore Bilbo’s funeral in 1947. His long career of civil rights reporting began then, writing for The Times Picayune until that New Orleans paper closed its Mississippi bureau. In his last decades, he wrote syndicated columns that did what they could to keep the state’s politicians accountable and honest.

Throughout his long reporting career, Bill Minor made enemies, the right enemies, and was threatened and sued and maligned.

Our paths crossed in the early 1980s in the Capitol Newsroom in Jackson. Minor was introduced to me as the dean of Mississippi journalists, a title he earned. He also was a really nice guy.

As a reporter for Jackson’s struggling United Press International, I quickly learned that Bill was the man to see if you had a question about anything to do with the state’s byzantine politics. He had the key to the vault of institutional knowledge. And he didn’t mind sharing.

I last saw Bill in Athens, Ga., at an annual gathering of old civil rights reporters given an ironic lofty title, the Popham Fellowship. It was named for John Popham, a celebrated New York Times reporter who traveled the South to the tune of 50,000 miles a year. His race reporting was the gold standard.

I was there to write a column in 1999, the year Popham died. The decision had to be made whether to continue the yearly gathering. It was an emotional, inspirational scene. I’ll never forget the arrival of one of my professional heroes, Bill Emerson, formerly of Newsweek, holding his portable oxygen apparatus in one hand, his whiskey bottle in the other.

I can’t remember how the vote went about future meetings, but I will remember till I die roaming the halls of the unremarkable chain hotel amongst the giants of our print trade, including Bill Minor, Claude Sitton, Joe Cumming and the aforementioned Ray Jenkins. The war stories were from the front line. The wit and stamina was legendary. An era was winding down, but not quietly.

When Chet Huntley retired from The Huntley-Brinkley Report in 1970, the network gave him a horse because he was moving home to Montana.

Huntley lived only four years after retiring.

Bill Minor died last year at age 94, still reporting and writing until almost the end, when he became too ill. His last columns were among his best; there was a lot that needed saying.

He never left Mississippi or abandoned his hope that race relations and hearts here could change. I am not alone in missing him.

|

|

Across the Bridge - Dec/Jan 2017

|

|

A few years ago, friends gave me the album “Blood Oranges in the Snow” by an Ohio husband and wife folk duo that calls itself Over the Rhine.

I must have listened to the CD 300 times. The couple writes amazingly literate lyrics: We keep driving/we’re not afraid/ The snow in our headlights/Confetti in a parade…. But my favorite of the album’s holiday songs is not one of theirs but a cover of Merle Haggard’s “If We Make It Through December.” Who amongst us hasn’t felt the soul-sapping dread of snow-plowing through the most sentimental of holidays on less than all emotional cylinders with not enough money, wanting to be somewhere else? |

Across the Bridge

|

That’s when it’s time to put one Size Nine in front of the other and carry on. If you think you’ve sensed a mood here, you have. I don’t mean to hate December/It’s meant to be the happy time of year…

Sometimes by simply going through the motions you get caught up and carried along. So I trudged through the carpet of leaves to the storage room behind the car shed. In it are the Christmas boxes shoved haphazardly into hibernation in past years. Starting the intimidating task of unloading decorations didn’t make me merry, but it did make me thankful.

I put “Blood Oranges” in my boom box and began.

There is the music box my sister made in ceramics class back when there was such a thing as ceramics class – back before double-knit. Mr and Mrs. Claus dance before a mantel with stockings to the tinny music of “I Saw Mama Kissing Santa Claus.” On the ceramic calendar hanging by the ceramic fireplace the date is December 24, which is exactly when the handmade gift arrived in Jackson, Mississippi, the year I Iived in a South Jackson rental we called The Smurf House. My former husband and I shared the big house with several single men, and the Smurf theme seemed obvious and stuck.

The two vintage plastic snowmen come tumbling from another box, top hats at jaunty angle. I remember the first Christmas Terry Martin spent across the road from me in his little red house. He gave me those retro Frosties. The warm feeling having him so close gave me was the real gift. How many people can say their closest neighbor is not just a geographical accident but someone in philosophical and political agreement about almost every fundamental thing?

Not many. We are blue dots in an ocean of red.

The red sled my niece Chelsey made from Popsicle sticks remains intact, despite my careless packing. So does the Plaster of Paris snowman with stick arms. A friend’s child sold me that treasure from his private fund-raiser.

Children are not only clever but enterprising.

By my sofa are a dozen or more of those home and garden magazines that make you want to burn down your own house and start over. I wonder where the people with thematic, color-coordinated trees and rooms stash their stick sleds and Plaster of Paris snowmen. Worse yet, how do healthy people justify not decorating at all?

Next from the bubble wrap rubble comes the chalk Santa my father won for me at a Florida county fair. I was six. He was deft at pitching nickels. The games back then evidently weren’t rigged.

And if the Santa is coming out, so must the snow globe my mother mailed at great expense when she heard my modest collection had frozen and burst. The event cured me of collecting, but Mother insisted I should have one globe at least.

I find the straw animals my friend Edwin “Whiskey” Gray has given me over a dozen years. They are the ornaments that remind me of France, not unlike the ones sold at the flower market that surprises you when you emerge from the Metro. Chelsey once told me that anything I really love reminds me of France, and I guess that is true.

Speaking of. I search for and find the three French hens painted on a red egg replete with the Eiffel Tower.

Unpacking accomplished, I’ll next bake the late Lera Johnson’s oatmeal cookies, a recipe that makes enough to share with her two grown sons. Back when folks cooked with Crisco and I was young, hungry and skinny – not to mention terrified of what the future held -- there was one thing you could count on. Whenever I stuck my hand into my mother-in-law’s cream-colored cookie jar, I never once hit bottom.

Lera Johnson’s Oatmeal Cookies

3 cups Quick Oats

1 cup brown sugar

1 cup white sugar

1 cup Crisco

1 cup nuts

2 eggs

1 and a half cups flour

Cream sugar and Crisco; mix in eggs, oats, flour and pecans. Bake at 300 degrees until brown.

|

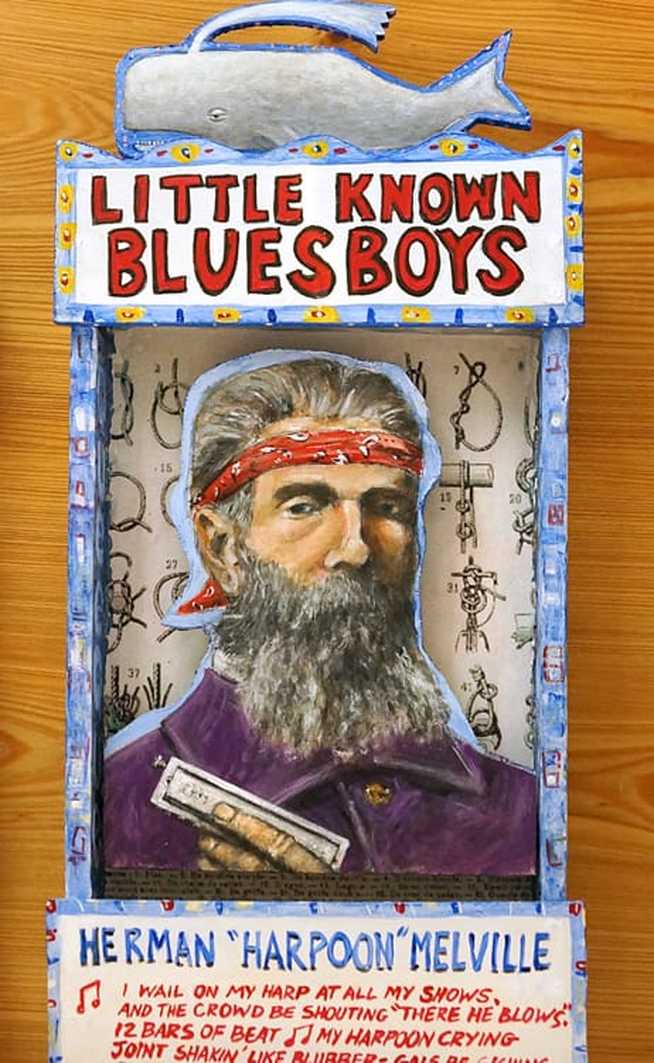

Above my bed in Iuka hangs Cat Island in all of its glorious aquarium-colored shadows, a pastel done in gauzy hues to keep me sane and calm when I’m far from the shore. My friend John McKellar of Bay St. Louis is the artist.

I never know where to start when talking about John’s talent. His “serious” landscapes are among my favorite paintings anywhere. But then there are his fun and folksy projects, for instance, the “Little Known Bluesboys,” including “Lil Willie Shakespeare, Trump, Picasso and Herman “Harpoon” Melville: I wail on the harp at all my shows, And the crowd be shouting ‘There he blows….’ |

Across the Bridge

|

You might say John is the Sybil of coast artists, with multiple personalities, defying categorization and having fun.

I went to a recent “pop up” exhibition – I question that term; nothing as good as this “pops up” like a ring of mushrooms -- at the Ohr O'Keefe Museum of Art’s Creel House in Biloxi. Along with John and Kerr Grabowski of the Bay was Mary Hardy of Ocean Springs. The talent was thick enough to spread on French bread.

The small cottage was so full of admiring art patrons that I had to spend a lot of time outside near the taco truck. It was exactly the kind of enthusiastic turnout that gives the coast its well-deserved reputation for artistic appreciation.

I’ve spent the past year trying to start a shoestring gallery in Iuka, population 3,000. I’m making it up as I go along, and learning a lot about art and humanity. From my perspective, it would seem there are far more good but starving artists than patrons, at least in my particular neck of the woods.

Almost every day, some eager artist without a place to show his or her work arrives with an excellent portfolio, often stored on a telephone. I don’t have the room or budget to accommodate all the deserving painters and photographers and potters who drop by. It is a shame, really, how much talent stays stacked up in remote studios instead of hanging on museum or gallery walls.

I’ve puzzled much over the difference between communities that don’t just embrace but bear-hug the arts, compared to those towns that think a painting is a frill meant for rich folk.

It is not.

When I was a young girl, my mother bought the kind of art she could afford: two prints in cheap wooden frames of Asian street scenes. She didn’t pay money for the art, but swapped the Top Value stamps she collected at the Kwik-Chek grocery store in Pensacola, Fla.

Now even at the Top Value redemption center there were more practical choices than art. Lamps, cookware, dishes. Mother, however, seemed hungry for something pretty to look at as she went about her housewifery day after day. She chose art.

I can remember sitting on the floor beneath the two prints and making up stories to go along with the rather generic street scenes. In one, a beautiful woman was scurrying along, and I imagined where she might be headed. I never gave out of storylines, which sometimes overlapped with what I’d last seen on “Gunsmoke.”

That’s what art does, in a way. It transports us to places we may never visit, inspires us to think about both foreign ports and home in a different light. It makes us yearn to be seaside, or in the mountains, or on top of a worn bedspread next to a yellow dog.

It sometimes makes us laugh.

John’s Cat Island is the South on my inner-compass, a destination hidden in my heart and head.

In the Eye of the Beholder

|

I’ve gone through most of my adult life expecting gracious living just around the corner, believing that one day I’d wake up and find myself in a Renoir garden outside of an Architectural Digest house in Audrey Hepburn’s clothes. I dream big.

It’s come to my attention this summer that this is never going to happen. Hope has been vanquished. Guests arriving in a steady stream from the beautiful coast to my humble, workaday place in northeast Mississippi have served as reality check. They are all deserving of the best I have to offer. And I suddenly realize it isn’t much. I was shabby before shabby was chic. |

Across the Bridge

|

I do my best to stage it for visitors. I cut and clean and hide and polish. I even wash windows. But minutes before the scheduled arrivals, I take a look around and see the truth.

The yard is a yard, not a lawn, and it looks good for approximately half a day after mowing.

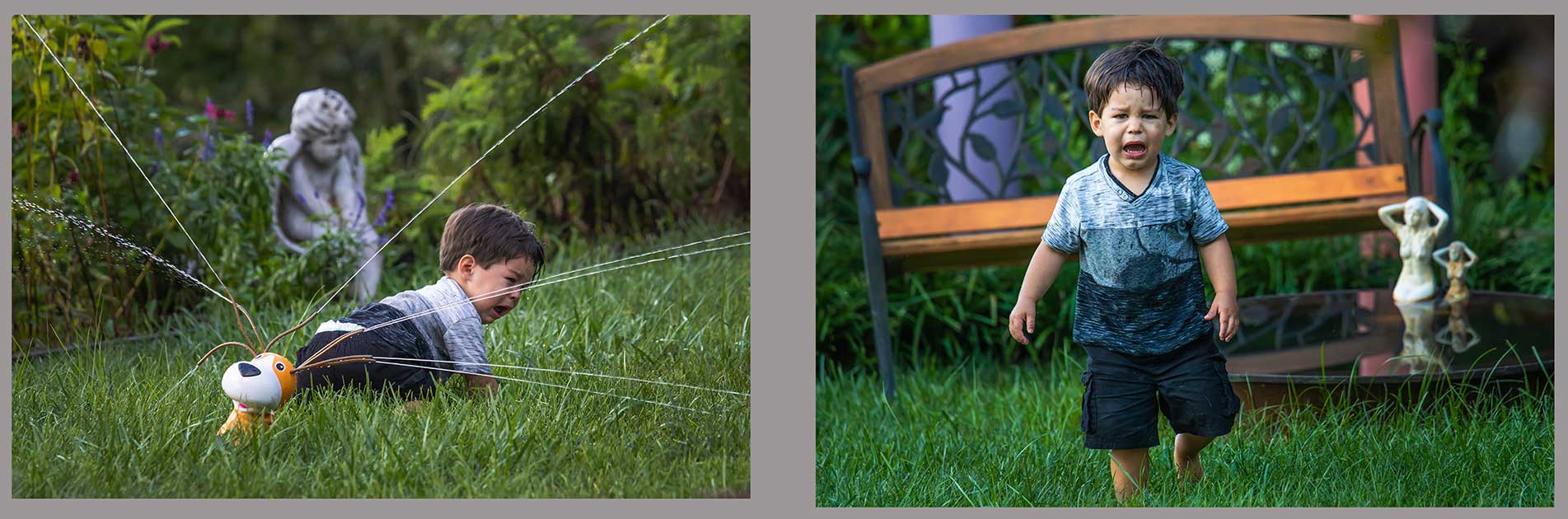

Then the briars and the weeds and the gum balls begin to compete for attention, and visitors realize the endless river of green they first glimpsed is hopelessly polluted. It’s not a space for playing croquet, but more like a practice field for teaching youngsters how to drive a pickup with a straight shift.

The “house” really is a collection of two small cabins, one bedroom and one bath respectively, made less claustrophobic with a screened porch tacked on each. You better like your hosts and those with whom you travel when you land here.

And don’t think quaint. There is none of the “cottage charm” that Bay St. Louis residents take for granted, but instead a 1950s look with low ceilings, thin floors, inherited furniture and too much sentimental swag. Clutter is clutter is clutter.

As I sit wondering what the latest guests must think, they tell me.

A visitor cries out, and I think she must have slipped on the mildew-covered walkway between the cabins, something I’ve done myself. “Look, look,” she says, pointing. One of last night’s crop of luna moths is sticking around. They routinely beat against the wickedly irregular windows in the back room, drawn to the light.

Together we study the moth’s green velvet wings.

The next day I take them to the old pontoon boat that floats in a nearby Pickwick Lake marina. Earlier in the season I’d wrapped the cracked vinyl seats like big birthday gifts with a few yards of sale cloth in a color that matched nothing else on the boat.

“Oh, what magnificent spider webs,” one visitor says, just as I am about to knock the webs down with a broom I keep aboard for that purpose.

In a world where people like lively entertainment, a rock wall is a quiet anomaly. But my visitors get it.

We picnic on the Tennessee River along the Natchez Trace. The breeze is constant, the conversation lively. And suddenly I’m proud of where I spend half of each year, half of my life. Domestic imperfections seem inconsequential, dwelling on them silly.

If you invite the right people, if you have the right friends, gracious living is a given.

Someone Who Mattered

|

When someone you love dies, people irritate you. Friends especially. Lots of them do, anyhow.

Here is a for-instance. The ones who come up and ask you what stage of grief you are in are beyond irritating. “What stage are you on?” was how I always answered. Grief may have stages but they are in such a constant muddle that anger bleeds into denial that may, in an hour or so, morph into bargaining or depression, and so on and so on. Some wag once said that everything learned in sociology is either obvious or untrue. How obvious and true. |

Across the Bridge

|

Many wanted to compare their own grief with mine, as if we were in a global grief competition. When my mother died, they’d begin, meaning well and telling best how to cope, irritating beyond belief. Or, someone might recall with misty eyes, when my husband died 30 years ago, I swore never to remarry and have not. Bully.

They congregated on my porch and ate and drank and laughed, all in the name of keeping me company. I wanted desperately to be alone. They left me alone when I wanted company. Fools, fools, fools.

Everyone had an opinion about honoring the dead. Some lobbied for marble, replete with dates, else The Almighty would not know the deceased was deceased. In-laws and friends wanted some of the ashes to feel more a part of the sorrow. I resisted.

I wanted to scatter most of Don’s ashes by myself in the Atchafalaya Swamp. I thought it fitting. His happiest hours were in that swamp. By himself.

Problem was, I had a plan but no boat. But I knew someone who did.

I drove all day from North Mississippi to Henderson, La., straight to the home of a friend who did not irritate me. Not then, not ever.

Greg Guirard was standing in his yard as if we’d had an appointment. I told him my mission. “I’ll take you to a pretty place,” he said. That was it.

The pretty place was Bayou Benoit. Greg had a houseboat bobbing there. He disappeared, not literally, but leaving me alone to the most private of tasks. I don’t remember that he said a word. No intrusive or sentimental claptrap worthy of Hallmark. No suggestions about moments of silence. No toasts. Certainly no prayers.

Greg got us back to the landing and my truck before dark.

When Greg died last month, I mourned again. This time I find myself on the irritating side of the grief equation. He was a man who meant so much to so many people that I want to grab strangers by the lapels and tell my Greg stories, to explain his worth again and again. Now I am the noise.

What was there about his calm presence that inspired so many? He taught literature, wrote books, took countless swamp photos, fought environmental battles against oil companies with his fellow crawfishermen. He reclaimed sinker logs, made beautiful cypress furniture, planted oak and cypress trees, lived simply, honored his elders, had an amazing sense of humor and was one of the best-read men I’ve ever known. And he helped a widow scatter her husband’s ashes.

But none of that exactly explains why he will be remembered when so many of us will not.

It is tempting – and irritating – to make a dead Greg into a super hero.

“Greg,” I once said to him while tagging along to check crawfish traps. “You are a beacon of contentment.”

“I’m a beacon of Lexapro,” he retorted.

He was the most guileless of heroes, the most modest of men.

For my money, it was mainly this that made Greg Guirard unforgettable: He knew when to stop talking and listen. His deafness made him bend forward as if he wanted to hear everything you might utter. As if yours was the most important voice, not his.

And now, I perhaps have sated your curiosity about a giant of a man. I will take a page from Greg and from here on remember him in silence.

Categories

All

15 Minutes

Across The Bridge

Aloha Diamondhead

Amtrak

Antiques

Architecture

Art

Arts Alive

Arts Locale

At Home In The Bay

Bay Bride

Bay Business

Bay Reads

Bay St. Louis

Beach To Bayou

Beach-to-bayou

Beautiful Things

Benefit

Big Buzz

Boats

Body+Mind+Spirit

Books

BSL Council Updates

BSL P&Z

Business

Business Buzz

Casting My Net

Civics

Coast Cuisine

Coast Lines Column

Day Tripping

Design

Diamondhead

DIY

Editors Notes

Education

Environment

Events

Fashion

Food

Friends Of The Animal Shelter

Good Neighbor

Grape Minds

Growing Up Downtown

Harbor Highlights

Health

History

Honor Roll

House And Garden

Legends And Legacies

Local Focal

Lodging

Mardi Gras

Mind+Body+Spirit

Mother Of Pearl

Murphy's Musical Notes

Music

Nature

Nature Notes

New Orleans

News

Noteworthy Women

Old Town Merchants

On The Shoofly

Parenting

Partner Spotlight

Pass Christian

Public Safety

Puppy-dog-tales

Rheta-grimsley-johnson

Science

Second Saturday

Shared History

Shared-history

Shelter-stars

Shoofly

Shore Thing Fishing Report

Sponsor Spotlight

Station-house-bsl

Talk Of The Town

The Eyes Have It

Tourism

Town Green

Town-green

Travel

Tying-the-knot

Video

Vintage-vignette

Vintage-vignette

Waveland

Weddings

Wellness

Window-shopping

Wines-and-dining

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

June 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

August 2014

January 2014

November 2013

August 2013

June 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

October 2012

September 2012

May 2012

March 2012

February 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

July 2011

June 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed