The author takes time to study the quietness of the forest and the unique qualities of its inhabitants.

- story by James Inabinet, PhD

Winged blue jays were doing bird-things: eating muscadine berries, building nests in early spring, picking aphids off of stems, and singing songs. Wiggling earthworms were doing earthworm things: tunneling just below the surface of the ground, eating leaves, feeding armadillos, squirming when encountering ants or sunlight.

Hopping frogs were doing frog things: sitting on lily pads, hunting insects, swimming, calling for a mate, and feeding snakes. Crawling fence lizards were doing lizard things: running over the ground, hunting, slipping tongues in and out of their mouths, performing push-ups to show off blue underbellies, feeding birds, digging under leaf mats, and remaining motionless when the shadow of a bird passes over.

Rooted red maples were doing maple things: limbs reaching toward the sun, growing tall in moist bottomlands, flowering and seeding in mid-winter, and feeding squirrels. The initial goal of the investigations was simply to make careful and detailed observations of anything that captured my interest. In the goldenrod field, for instance, I sought the unique character of goldenrod so as to understand its process of becoming, to understand how it became what it is. Not a form frozen in time, goldenrod grows and becomes, changing every day. Through detailed observations I noted how goldenrod expressed itself: basal rosette of fuzzy green leaves, long straight stems, robust yellow fall flowers. In the beginning, all goldenrods looked the same. Over time, the more I looked, the more I began to notice variations. I noticed that goldenrods in the field were usually small in stature, but large in flower while those in the forest tended to be large in stature and small in flower. Further investigations revealed individual differences. No two goldenrods were alike. I was eventually able to detect particulars for each one, a unique and individual character–though detecting that individual character was often difficult. After many forays watching animals, I noticed that after an organism’s needs were met, she would often sit idly, perhaps resting in a protected nook. A coyote near the bayou with a rabbit once panted under the low-lying limbs of wax myrtles. A frog-fed copperhead curled up on the creek bank in the shade of titi limbs. Satiated towhees sat on limbs, either singing or resting quietly. A finch left a bush half-full of berries and never returned - unless she slipped in and out without my noticing. It seemed that nearly all of the organisms I chose for careful study rested when not hunting or hiding or escaping. With no dire call to incessantly hunt and store food, enough seemed to be enough. In these ways and myriad others, I noticed that the characteristics of each organism amalgamated into a unique expression. Deathcaps of the forest floor displayed a unique sense of fungusness unlike that of puffballs. The squirrels of the canopy displayed a unique sense of squirrelness, an identity unexpressed by any other organism. Water oaks displayed a sense of oakness unique to their kind, an expression that I became so familiar with that I could eventually distinguish water oaks from others by gazing at twilight silhouettes from far away. I called each organism’s manner of being its identity. Each organism in the forest possessed a unique identity, unique as species, unique as individuals. The primary inclination of each individual seemed to be to express its unique identity as individual in its forest home. I longed to find out what humanness must be like in my forest home. I longed to find out my identity, to find out what Jamesness must be like if it were to be fully realized.

Hummingbirds, jewels of the Southern garden, are returning to our area after wintering in Central and South America. Find out how to welcome them home. - Story and photos by Dena Temple

Video (below) taken in Waveland in September, 2018 during the fall hummingbird migration. While 16 species of hummingbirds breed in the Northern Hemisphere, there is only one species that regularly inhabits our area, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The male is an iridescent green with a white underside and a red gorget (throat). As light is reflected off the gorget, it appears a fiery red; out of direct light, it appears dark. With wings that beat about 70 times per second, hummingbirds can indeed hover as well as fly backwards and upside down. They are interesting to watch and worthwhile to attract to your yard. There is no trick or special formula to attract hummingbirds. You just need to understand that all living things require three things to survive: food, shelter, and water. If you provide those things for hummingbirds, they will visit your yard, too. First, let’s talk food. Hummingbirds subsist on a combination of insects and the nectar from tubular-shaped flowers. While you probably won’t be able to set up an insect diner for the hummers, supplying nectar is as simple as putting out a hummingbird feeder. The feeder needn’t be fancy, or expensive; most wild bird stores and many garden centers have inexpensive feeders available. When selecting a feeder, be sure to choose one that is easy to clean, because you’ll be cleaning it often. My personal favorite is the Aspects Mini HummZinger (shown). It is extremely easy to clean and fill, and it comes with a lifetime warranty. Fill the feeder with a nectar solution made from one part sugar to four parts water. Contrary to popular belief, you don’t need to boil the mixture; just stir until the sugar dissolves. Mix only as much nectar as you need at that moment. And please, don’t use commercially available nectar formulations from the home center. They cost a fortune and include red dye and other unnecessary chemicals that may negatively affect your little lodgers. Hang your feeder in a semi-sheltered location such as under the eaves of the house, if possible, to keep rain water from contaminating the nectar. Clean your feeders often – at least once a week in cool weather, and more often in warmer weather. If the nectar looks cloudy or shows any mold growth, it’s past time to clean. The usual reason for lack of success in attracting hummers is setting out the feeder too late in the spring. Reports are already coming in from neighboring communities that the first hummers are back! Males return first to stake out breeding territories. If they find your feeder and the area looks safe, one may take up residence. In a week or two the females will return, looking for love – and an attractive territory. The right food plants can also make your yard more attractive to hummers. If you are planning on adding to your landscape, you might want to keep these plants in mind. (See list at the end of this article.) Shelter is the second requirement for attracting hummingbirds. If you have numerous trees and shrubs on your property, the birds have plenty of places to construct a nest or hide from predators. Water is the third requirement. A simple birdbath can be constructed from almost anything – a plate, a trash can lid (clean it first, please), a shallow plastic bowl. Again, be sure to keep the birdbath clean and shallowly filled. In our area, your first guest should appear in early March. You may not see regular activity at your hummingbird feeder for quite some time while the birds establish their territories. Once you start seeing the birds, note how territorial they are: One male will not allow another to use “his” feeder. If you hang more than one feeder, try to locate them so that they are not in direct view of each other, so one male cannot monopolize two feeders. Do not be surprised if your “guests” disappear several times during the summer season. When their favorite flowers bloom, they will feed only from the flowers, rejecting your finest offering. Don’t worry; they’ll be back. Also, breeding activity may keep them from being active in the garden. But just wait: if you provide them with suitable nesting habitat, you can enjoy watching the young hummers cavort around your hard all summer long, until they begin their southbound migration in September. Their games are enchanting to watch. As autumn approaches, you will see less and less of your guests as they begin their long migration to the tropics. You have helped make this trip possible by supplying them with the energy they need for this arduous trip. Do not be sad at their leaving; if all goes well, the same birds may reappear next year. Fall is the time to double up on your feeders; you will probably need to refill them daily to keep up with demand. Then, as hummers migrate south from the rest of North America, get ready for Invasion of the Migrants! An entire continent’s worth of hummers will stream past, pausing before making the arduous trip across the Gulf of Mexico. The amazing video above was taken at a Waveland feeder in mid-September. Keep your eyes open for rare migrating Western hummingbirds that occasionally lose their way and end up along the Gulf Coast. Hummingbirds make an attractive and interesting addition to any summer garden. It is well worth your while to invite them to spend their summer vacation at your “resort,” where they fascinate and captivate. All it takes is a few pennies’ worth of sugar – and a little patience.

A giddy newcomer and seasoned bird-watcher finds a wildlife bonanza here on the Gulf Coast.

- story by Dena Temple

Black Skimmer feeds by dragging its lower mandible through the water, trolling for fish.

“Tu-a-wee!” A flock of Eastern Bluebirds frolicked in the front yard.

Yes, we are birders. Bird-brains. Bird nerds! In fact, our fascination with feathered fauna helped drive our southern migration. And as birders, we weren’t looking for a home so much as a “habitat.” The pretty brick house on the tracks in Waveland fit the bill perfectly – lots of land bordered by dense woods, near a bayou. We signed the papers just before Thanksgiving, and by Turkey Day we were unpacking our binoculars and setting up feeding stations. We’re also a little competitive. And by “little,” I mean very. We compete with other bird nerds to see how many species of birds we can ID in our yards. We re-started our 2018 list when we moved to Waveland – and by the time the ball dropped on New Year’s Eve, our list stood at an astounding 52 species. In five weeks! While all seasons along the Coast provide excellent opportunities for wildlife-watching, perhaps the best kept secret is the diversity here in the winter.

Joining the resident species of the Gulf are thousands of birds that spend their summers breeding farther north. As lakes and bays freeze over, species that rely on aquatic habitat are forced to head south.

In addition, land birds that eat insects must migrate to follow the food source. So, while spring and fall offer the best variety because of the migratory birds passing along the Mississippi Flyway, winter birding delights savvy Gulf Coast residents who are “in the know.” Gulls, terns and particularly shorebirds flock to the Gulf beaches, much like our snowbirds do, for the Gulf’s agreeable climate and excellent dining. Everyone eats seafood along the Coast! Ducks, too, migrate south for the winter. Many only go as far as necessary to find unfrozen water, so they can find food. Some, however, make their way to our coastline and local ponds. Commonly seen from our beaches are Bufflehead, tiny black ducks with white bonnet-like caps, and Common Loons, looking drab in their “basic” winter plumage. One of my favorite places to look for birds is the Washington Street Pier in Bay St. Louis. What makes any location excellent for birds is habitat diversity, and this spot has it. Along the beach you’ll see lots of terns, gulls and shorebirds. Try to pick out the Willet, a large shorebird with drab, brown plumage – until he flies, revealing a distinctive and brilliant white wing stripe. Walking to the end of the pier, scan the water for the aforementioned ducks, along with Horned Grebes, which are common in the Sound in the winter, and Red-breasted Mergansers, ducks with a distinctive dagger-like bill. Next, scan the rocks at the pier for Ruddy Turnstone, a medium-sized shorebird with orange legs and an unusually patterned chest. Perhaps you’ll get lucky and spot a Purple Sandpiper in the rocks, a rare visitor from the North. While you’re out there, scan the distant skies for the beautiful white Northern Gannett, a large, graceful booby-like bird that nests on island cliffs but spends its entire winter over the water. Back on land, patiently check the dune grass for birds like Marsh Wren, sparrows and Scaly-breasted Munia, a non-native, pet-shop escapee that has been spotted here recently. There are many places along the Gulf Coast where beginners and pros alike can enjoy looking at, and learning about, birds. A great source is the Mississippi Coast Audubon Society, which hosts mostly free field trips to various locations in the area. Attending one of these trips is a great way to meet like-minded people, increase your local knowledge, and learn about conservation and habitat protection. If you’d rather strike out on your own, you can find information on the website for the Mississippi Coastal Birding Trail . The website identifies more than 40 prime birding locations in the six southern counties of Mississippi. It’s a great resource, and I’ll be working my way through that list myself. If you are the type who likes to volunteer, there are opportunities through both MCAS and the National Audubon Society for winter shorebird monitoring. Also coming up February 15-19 is the Great Backyard Bird Count, which encourages individuals to count birds in their own backyards (or a local park or hotspot), then report your findings online through a special website, www.birdsource.org. The event is held over Presidents Day weekend, which may give you an extra day to venture out and enjoy what our area has to offer.

A local naturalist and zen explorer experiments with ways to consider the world from another living creature's perspective - and discovers a new way of seeing.

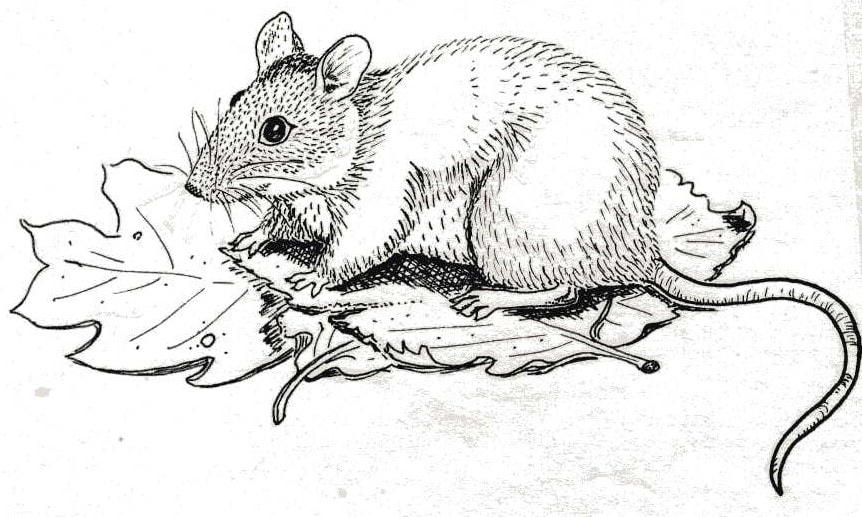

- by James Inabinet, PhD, illustrations by Margaret Inabinet

Mouse-seeing is an innocent way of seeing that begins with an empty mind, a “beginner’s mind,” one open to anything as Zen master Suzuki describes: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.”

To begin mouse-seeing, thinking is suspended through meditation or prayer. A quieted mind allows the “seer” to become more mindful of what’s happening right now, right here. With an empty mind one becomes like a hollow bone, ready to be filled with possibility. Several years ago, I ritually began my first journey into mouse-seeing in the goldenrod field. After sitting in meditation for a while, I dropped down and put my nose close to the ground like a mouse to see the field up close the way she would. I could see thickets of grass and goldenrod stems. With lowered head, I crawled for a while seeking mouse roads below the grass and goldenrod “canopy” and experience being in mouse habitat as I moved mouse-like through the field. After a half hour or so, I became bored and noticed that I had been thinking about home and work. I meditated and began again. Soon I stumbled onto what appeared to be a tiny trail. I slid onto my belly to look closer and discovered a mouse trail, a round hole through grass “trunks.” Opening back into the grass, the trail disappeared in shadow. Perhaps a tiny nest was back in there but I would never know. To get close enough to gaze at it would certainly destroy it.

I turned away and crawled towards the early sun. It struck me that humans are upright strangers that blithely walk through woods and fields as hawks, seeing from afar, from on high. We rarely see a mouse or even her signs and yet mice are legion, numbering in the thousands in this place alone. There on mouse roads they run, doing the doings of mice everyday unnoticed until someone gets down on her belly and looks with mouse eyes. Only then can mice and their way of being truly begin to exist for us.

As infants, we once possessed unmitigated body-knowing, as innocent as a mouse on her mouse-road – I only have to remember how to do it. Maybe I can return somehow to an infant’s sense of wonder, alert and curious – like a mouse. Intimate with her world, she sees clearly only what is right in front of her feeling, smelling nose. I moved closer to the stems of the grasses and goldenrods; I touched them with my face, feeling their roughness. Nose to the ground, I smelled the dark, damp earth where it was exposed. I listened closely while simultaneously smelling, feeling, looking. The mouse way is a doing way.

Energetically, I moved through the field, stopping only for brief moments. I alternately blurred my vision and then focused. In blurring, movement can be detected, vital in a mouse world that includes hawk shadows and snakes. With blurred images, one feels more than sees. Blurring interdicts thinking.

With closed eyes I laid down and focused on feelings. A surprisingly rough grass stem was touching my face. I tried to move into that feeling of roughness–without thinking. Moving my face to the side, I felt the mat of dry grass that covered the bare earth, again focusing on feelings. Moving forward a few inches I felt a grass stem on my forehead, focusing on feelings even as an image appeared, an image of what that grass might look like. I continued in this way for about an hour and had moved only about six feet. At the end of this experiment into mouse-seeing, I knew that particular feelings had arisen in me about the nature of the beings of the field, but I could not clearly recall them. It occurred to me that by purposefully suspending thinking, these feelings could not easily become thought and/or words. Something, though, was felt, something known, but I could not say exactly what it was. Even so, my relationship with this place deepened.

Crossing paths - and then following - a snake hunting dinner in the woods sparks a contemplation on how humans can relate to other beings in our world.

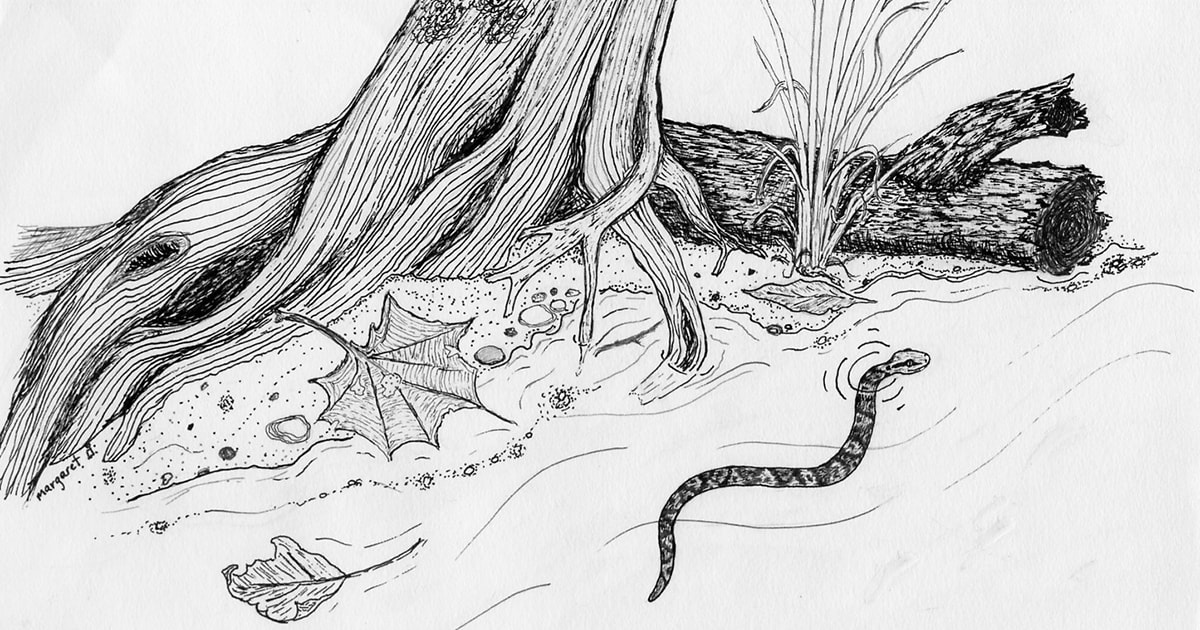

- by James Inabinet, PhD

The immovables joined in; scale insects covered moist, succulent stems: goldenrod, asters, Joe-Pye weed. Spittlebugs ensconced below; basal leaves pushed back revealed frothy hide-outs. Cocoons were packed snugly inside rolled-up leaves or dangled under them.

A golden silk spider web blocked the way, a micrathena orb-web right behind it, a spiny-orb weaver web next - signs of late summer. Contorting my body, I went under them. I made my way down the bluff overlooking the creek. Barefoot, I sloshed downstream on the sandy bottom; water just covered my ankles. The roar of cicadas drowned out the rippling water as I approached the confluence of bayou and creek through a tunnel of overhanging limbs and branches. A clearing signaled my approach to the bayou ahead. Movement along the bank next to the trunk of a smilax covered gallberry at the water’s edge revealed a slithering water moccasin. The poisonous snake wended his way into the bayou, hugging the edge. I followed – at a distance. Excited, I watched him slither, weaving back and forth, and then suddenly stop. Motionless except for a wagging tail, he steadied himself, apparently watching something. He remained this way for a long time, several minutes (!), and then struck blindingly fast. A frog jumped to safety, disappearing near the edge while the snake frantically searched. After a minute or so the snake resumed his journey downstream. It occurred to me that this must be the dance of a snake. I followed him, wondering what it might be like to be a snake and slither in the water in this way.

Later, I thought about: “What is it Like to be a Bat?” an essay by the cognitive scientist Thomas Nagel who famously wondered about the consciousness of creatures like bats, forms of consciousness very different from that of humans.

He surmised that there must be “something it is like” to be that organism. In order to determine “what it’s like” to be another being, humans use human points of view by imagining the other to have experiences that are similar to their own. Bats experience the world through sonar, a mode of experience profoundly unlike anything in human experience. Nagel found no reason to believe that batness is like anything “we can experience or imagine.” Concluding his thought experiment, he declared that there is simply no way to know what it is like to be a bat. I presume that knowing what it’s like to be a snake to be no different. Should I forget about the snake? This question cuts to the core of my research of the past 25 years, which is to come to know a forest ecosystem and its inhabitants deeply, even mystically, like a forest monk. The goal: to become a functioning human component within in an ecosystem, a functioning part of its wholeness - to fit in - like our snake or a bat or even a tree for that matter.

If Mr. Nagel remains distant from nature, sitting in his ivory tower armchair watching bats circle a streetlight through a window, he will never know batness and will conclude that no one else can. He could never experience a forest in the way I am seeking.

Because consciousness is subjective, all about me, the experience I have of another being, even a human one, remains difficult to describe. How can someone get to know “what it’s like” for another being? To know “what it’s like” there must be elements of experience where the one is like that of the other. There must be elements of experience we both hold in common. This is what empathy is – feeling the experience of the other. I tear up when you cry because I feel it. Nagel seems to reduce experience to thinking; indeed, he seems to elevate thinking to the order of actual experience wherein what passes for knowledge arises from thinking alone. To look at experience this way is to impose a purely “mental” form of consciousness onto humanity, leaving only a shell of experience. “Thinking” about bats becomes the only way to know about batness at all. You don’t even have to go outside and watch them. Of course, experience itself is always richer than thinking and speaking about it. Thinking about my love, for example, is one thing, but getting a hug from her is so much better. I propose that there are other valid, more experiential, ways of knowing than Nagel’s mental knowing. I propose that “body-knowing” is one of those ways. We have all felt parts of our bodies tightening up or relaxing in the face of profound experience, like the feeling of dread in a place that feels “off.” With body-knowing we know something even though we cannot say what we know - and no amount of thinking can help us to tell. Another way of knowing that I propose is what I call “heart knowing.” It’s a profoundly feeling-oriented, emotional, and empathetic way of knowing, not unlike feeling love for a partner. I have found that you can actually look at and dwell-within another being - even a non-human being - in this manner. If there is any way for humans to experience snakeness, it would seem to require one or both of these other ways of knowing. I am paraphrasing the philosopher Bruno Snell when I add that perhaps a human might never be able to experience a snake or a bat in a “human” way if she did not first experience herself - a human being[!] - in a “snake” or “bat” way. For experience to rise to that level requires more than just thinking about snakes or bats. Following Snell’s ambitious challenge, I have become determined to try a more embodied path to the experience of snakeness and see where that may lead.

Bay St. Louis is the hub of a five-state Gulf Coast plastic use reduction campaign. Find out who started the movement, who pioneered plastic-free in BSL and what local café is part of a pilot program.

- story by Ellis Anderson

Other Bay eateries will be joining PFGC as well, in a campaign offering drinking straws only-by-request. PFGC organizer Elizabeth Englebretson with the Gulf Coast Design Studio says that several have already agreed to participate in the effort to become more sustainable. Restaurants also benefit from building customer good-will and getting positive press exposure.

Englebretson says the effort stems from the fact that plastic pollution is continuing to increase, despite efforts to curb it. Calling it “a pandemic,” she believes the only way to stop the pollution is to cut back use of it to begin with, by using biodegradable options like paper and sugarcane-based “plastic.” The Mockingbird Café pilot program is being funded by a small grant through the Gulf of Mexico Alliance. Some of the grant money is being used to help pay for biodegradable non-plastics during the weaning away period. Customers are also being asked to pay a quarter extra. The pilot program grew out of inspiration from the Starfish Café’s successful effort to go plastic-free. The Starfish (211 Main Street) is a project of the non-profit, Pneuma Winds of Hope. Di Fillhart is the organization’s executive director and manager of the Starfish Café. Fillhart says the café started going plastics-free four years ago.

“We polled our customers and asked if they’d mind paying extra for biodegradable to-go containers,” says Fillhart. “Unanimously, they said, ‘no problem.’

Fillhart believes that the straws by request only is a good way for a business to get its feet wet in the burgeoning new green-market economy. “Our first step was to start with paper straws. Now we’re using a plant-based plastic straw.” Cutting back usage of the seemingly insignificant drinking straw might seem like a wasted effort. How could that alone make a dent in the enormous amount of waste produced in this country? But Englebretson says that US citizens alone use 500 million plastic straws each day. To put it in perspective, in a single year those straws could fill Yankee Stadium. Not once, but nine times over.

By tackling the drinking straw problem, the group hopes to raise awareness to let people know that they can add a fourth “R” to the saying “Reuse, Reduce, Recycle.” That would be “Refuse.”

Bay St. Louis is the hub of the pilot program that is slated to spread across the five Gulf Coast states, and the city is also the birthplace of PFGC itself. The organization began in 2016 as a project called Plastic-Free April. Three local women concerned about plastic pollution - Kerr Grabowski, Carole McKellar and Ann Weaver - led a public challenge asking people to go without using plastic for one month.

Last year, the group began working with the Gulf Coast Design Studio and Englebretson . The name of the group changed from “April-free” to “Gulf Coast” as the ideas blossomed. The movement now has partners in each of the five Gulf Coast states with ambitious plans for projects in them all.

“In the Gulf states, we don’t have a green economy where people have access to plastic alternatives,” Englebretson says. “We’d like to create one. And we’re even finding that some of the alternatives to plastic are now less expensive.”

“It’s not about going completely plastic-free right now. There are times you can’t avoid using it,” Englebretson says. “But it’s about making changes that eventually become part of your life.”

The Mockingbird has already explored sustainable-practice options through the years. The newly launched program, overseen by manager Whitney LaFrance, has is pushing the sustainability-business model envelope. Owner Alicein Schwabacher found herself asking, “Do we even need some of these products? And if if we do, can we replace the plastic with something less harmful to our ecology and customers?” “All of us at the Mockingbird want to be part of the solution,” said Schwabacher. Englebretson believes that sort of attitude can lead to big changes. “We just all need to work together and support each other,” she says. “We can make this happen.”

A state monitoring program tests the waters of the Mississippi coast and issues advisories if needed. What are they testing for and where? We have the info and the links to make it easy to check before you swim.

- story by Lisa Monti

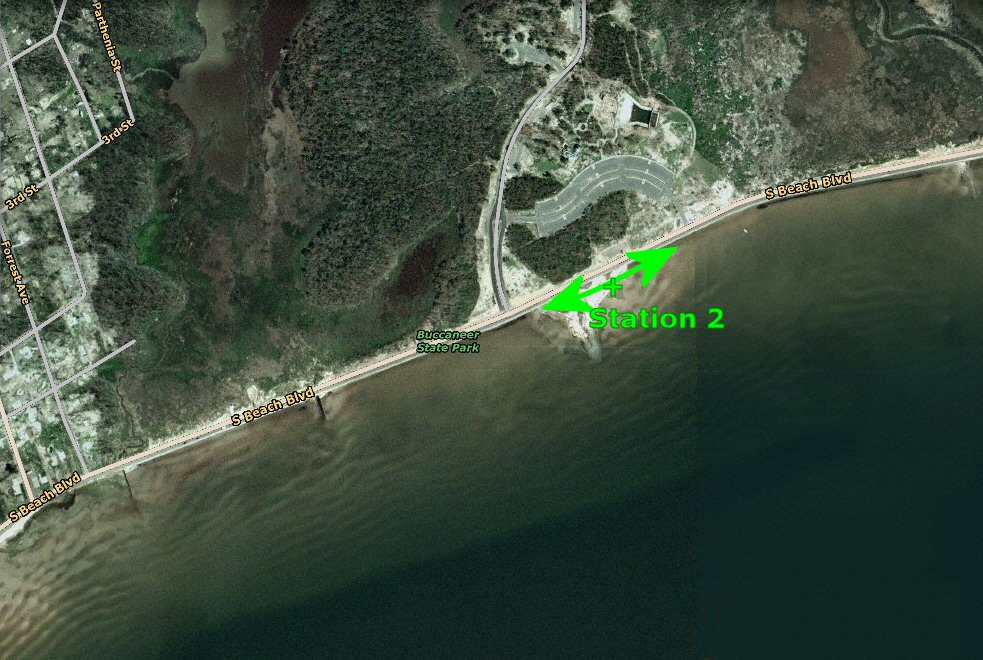

Doug Upton, chief of MDEQ’s field service division that does all monitoring across state, said the water samples are collected at least once a week by staffers at MDEQ’s regional office in Biloxi. The samples are analyzed at a private lab in Ocean Springs and results are typically reported in 24 hours.

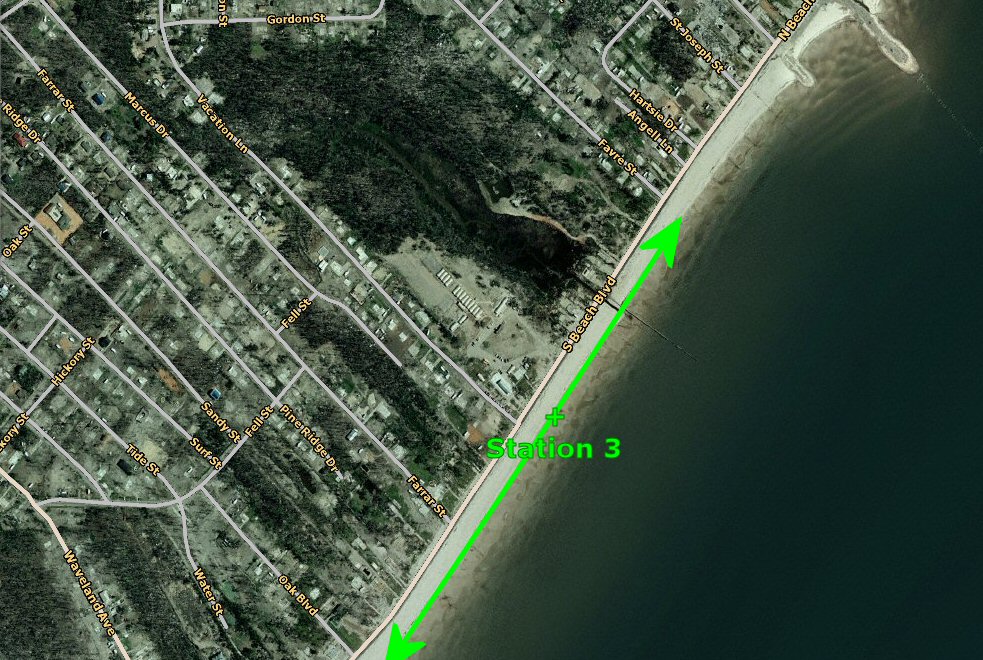

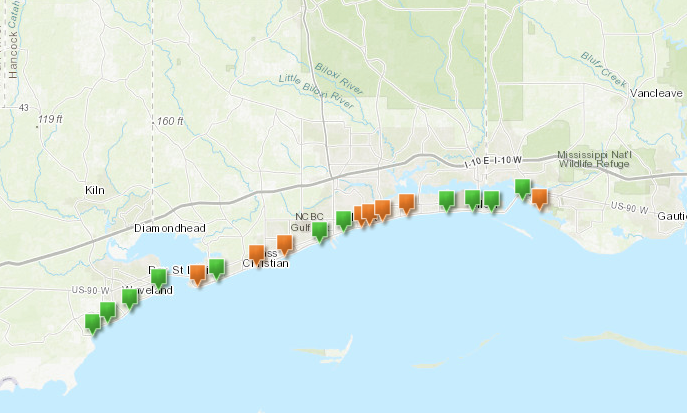

What they’re looking for is Enterococci bacteria, which Upton calls “an indicator organism” that signals pollution caused by stormwater runoff, wildlife, boating waste or sewer overflows. High winds and heavy rainfall can also increase bacteria levels in our coastal waters. That’s why the Beach Task Force recommends not swimming during or within 24 hours of significant rainfall. Below: the Four Hancock County Monitoring Stations

|

|

|

Beach to Bayou - Dec/Jan 2017

|

- story by LB Kovac and Ellis Anderson

|

Beach to Bayou

|

- Four friends in an SUV are heading out to dinner at a restaurant. It’s just after dark. They pull up to a stop sign at St. Charles Ave., when one notices movement in the wood strip just ahead where the road curves. It’s a fox! they breathe in awe, sitting at the stop sign, the headlights illuminating the creature. Time stretches, as they watch it watch them. Finally, the fox slips into the underbrush and vanishes. The friends drive on, understanding they’ve been gifted by nature on this night.

In fact, Mississippi is home to a substantial number of land mammals alone: 63. For reference, the Magnolia state beats Louisiana, the state closest in land size, by 11 species. Some of our furry neighbors, like the gray squirrel or the eastern cottontail, are a welcome sight no matter where you see them--be it on a nature trail or in your own backyard.

Yet some people may be dubious about critters like foxes, raccoons and opossums, critters important to the delicate Mississippi ecosystem.

Missy Dubuisson, owner of Vancleave-based wildlife rescue organization Wild at Heart, says that these are some of the animals her organization most often sees. She says, “we receive calls from federal, state and local law officers, and the general public” on a regular basis.

Dubuisson has been rehabilitating animals since she was a little girl growing up in Pass Christian. Her love for wild animals, especially America’s only marsupial, has earned her the nickname “the Possum Queen.”

“Many people see a possum and they think they’re going to attack. That’s not going to happen,” Dubuisson promises. She goes on to explain that they’ll only get aggressive if they’re on the defense. “Rightly so.”

As for rabies? The state has been surprisingly rabies-free for the past fifty years. According to the Mississippi Department of Health, “Land animal rabies is rare in Mississippi. Since 1961, only a single case of land animal rabies (a feral cat in 2015) has been identified in our state.” Experts found that the cat had contracted rabies after being bitten, not by another land mammal, but by a bat.

Possums, foxes and raccoons mostly live invisibly alongside humans in urban or semi-suburban areas like Bay-Waveland. All three creatures are dubbed opportunistic eaters. Possums feed on everything from roaches to slugs. Raccoons have a varied diet too, eating crawfish to berries. Much of a fox’s fare consists of invertebrates, like grasshoppers and caterpillars.

Fortunately for their human neighbors, all three eagerly devour nuisance rodents. The fox, in particular, is valued for its superlative ability to catch rats and mice.

Individuals can participate with the 40-year-old program, Garden for Wildlife. This step-by-step program guides homeowners in transforming an ordinary yard into a haven for birds and mammals that we love to watch. NWF even offers a certification once their checklist has been fulfilled. Signage celebrates the efforts and encourages neighbors to do likewise.

Schools, college campuses and place of worship also have wildlife habitat programs, tailored specifically for them. Entire cities, like Bay St. Louis or Waveland, can apply to be official Wildlife Habitat Communities. In addition to practicing more sustainable, nature-friendly lifestyles that benefit both humans and animals, these communities receive positive national recognition.

If Bay St. Louis or Waveland chose to participate, we’d be in good company: Disney’s Epcot Center is a showcase Habitat Community. As is the Denver Zoo. And in Maryland, “Baltimore Gas and Electric has created habitats along its power line rights of way.”

For more information on participating, click on the links above. In the meantime savor another sighting:

- Driving home from a college class in New Orleans one night, a woman crosses the tracks at Ballentine, heading toward the beach. The moon is full, so movement in a vacant field catches her eye. She stops the car. Two foxes freeze, their coats of red glowing, even in the blue moonlight. The human and animals regard each other calmly. There’s no fear on either part, only recognition as fellow beings sharing this extraordinary place and time. When the foxes decide they have better things to do, they move on out of sight. The woman slowly drives on toward her home, understanding that this brief encounter will be treasured for the rest of her days.

Legacy of Lovely: Carol Vegas

- story by LB Kovac, photos courtesy Holly Vegas

|

Holly Vegas said she didn’t know that city planners were naming a park after her mother until well after the grand opening on December 26, 2005.

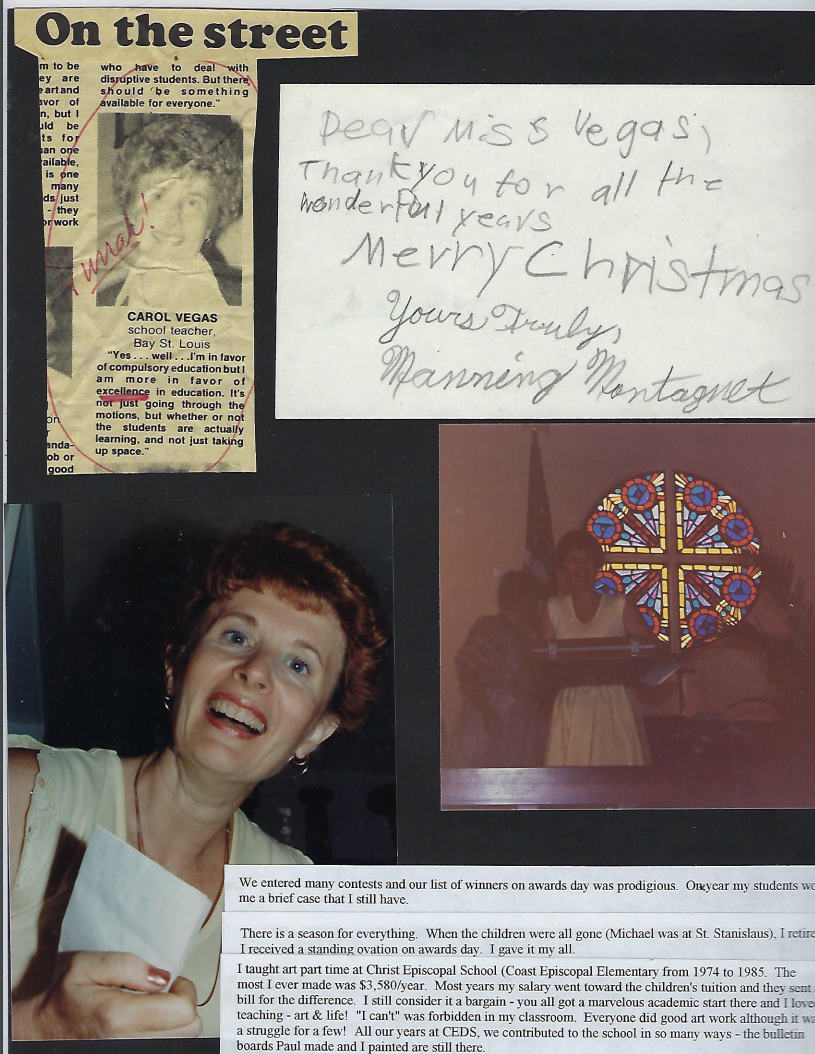

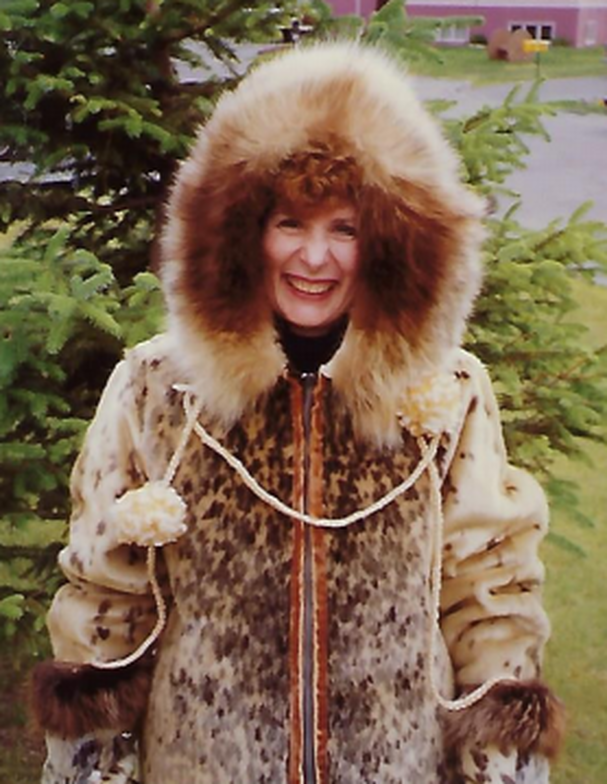

Holly Vegas, who lives in New York, says “I think I found out from a friend of a friend.” By the day of the park’s opening, Mrs. Carol Vegas had been dead for more than five years. But one thing she didn’t take to the grave was her legacy: Carol Vegas accomplished more than most in her 64 years alive. Carol Peterson was born on January 9, 1936, near Oakland, California. She didn’t make it to Bay St. Louis until April 1963. In between, she received a bachelor’s degree in art. |

Shared History

|

|

She was thinking about pursuing a master’s when she met Paul Vegas, an engineer, on a blind date. Holly says that it wasn’t in her plans to fall in love, but they were married in 1956. “Paul was her rock,” says Holly. “He gave her the strength to do what she did.”

She then moved to Guatemala when Paul got a government job working on the Pan-American Highway. She knew no Spanish, but she taught herself. She knew little about cooking meals, but she learned to, among other things, “kill the food to get it on the table,” says Holly. |

Carol Vegas in 1938: she came by her love of hats at a young age

Carol Vegas in 1938: she came by her love of hats at a young age

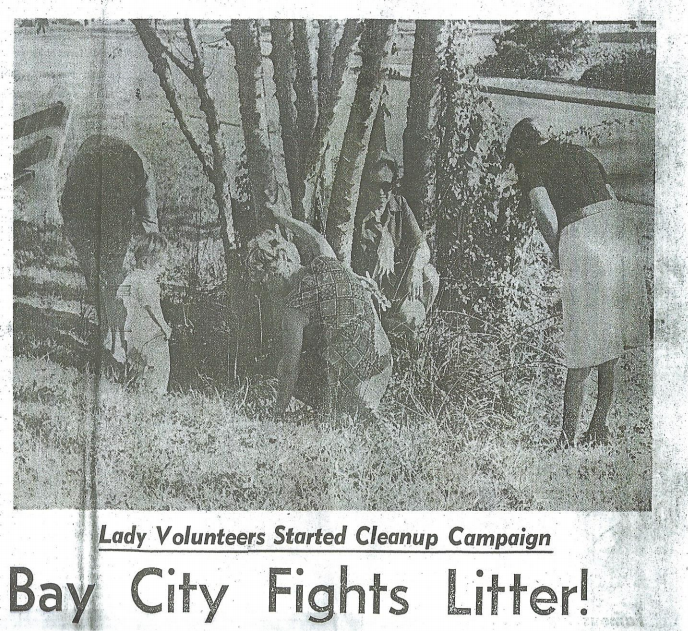

And this beautification business that Carol Vegas is now so famous for? Holly says it all started because of trash. “She was infuriated by people throwing their junk out,” she says. And, once again, she did what needed to be done. “She wanted the new place she called home to be a better place.” Carol and three other ladies organized a group of kids who would pick up trash in the mornings and on the weekends. “That’s what I remember about growing up: always being dragged around to pick up litter.”

“She would never not do the right thing,” says Holly, and this strong sense of ethics is something the daughter feels she inherited from her mother. “And, if there was something to be done – a party or whatever – she would do it to the nth degree.”

“[Her] biggest project was anti-litter.” Of course, where this litter was mattered little to Carol Vegas, or Cuevas. Together they served on the Bay St. Louis Beautification Committee, the Hancock County Beautification Committee and the Marine Debris Taskforce, where they helped on numerous projects that made the neighborhoods, roads and beaches less trash-filled and more beautiful.

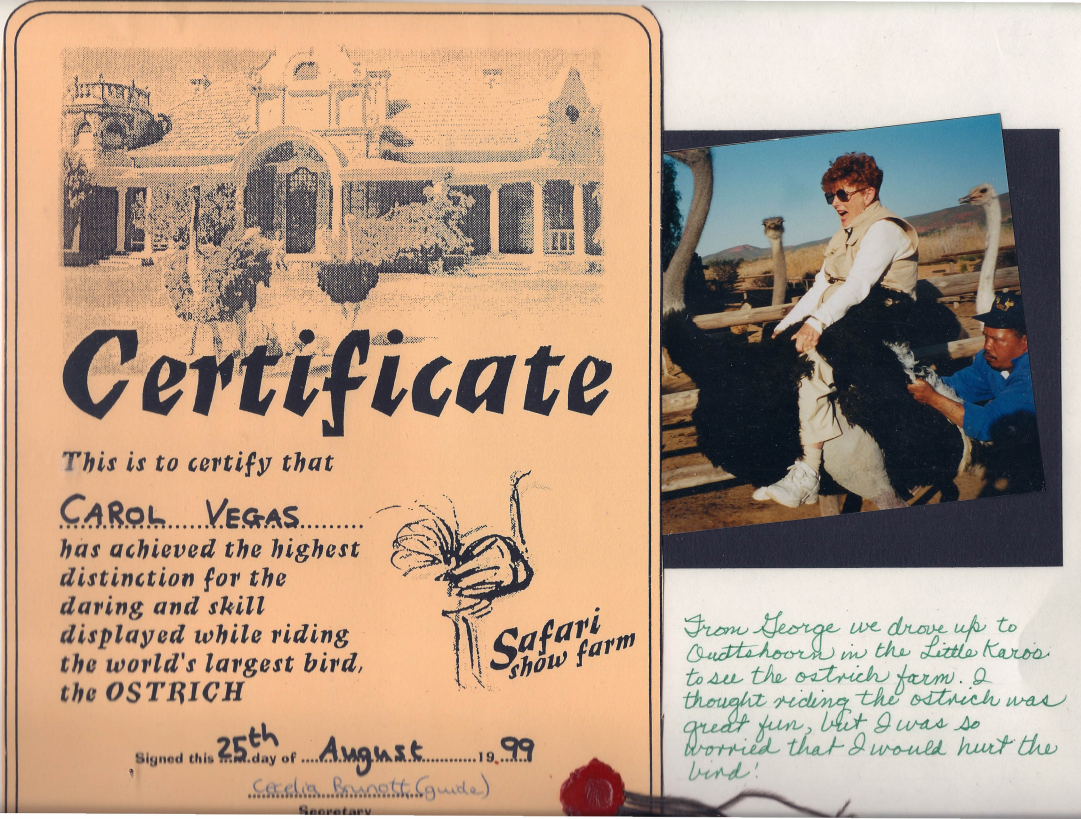

Independent of Cuevas, Carol Vegas also served on several highway landscaping committees and city beautification projects. She’s credited with designing the Tree of Life at the Harriet Center and the rose window at Christ Episcopal Church. For her efforts beautifying the Gulfport area, Carol Vegas was awarded medals, titles, plaques and other awards too numerous to even list.

Picking up litter certainly isn’t the glamorous side of beautification – not like designing gardens or arranging ornamental flowers – but it is important and necessary. Carol Vegas made a career out of it.

If you ever see the sunlight coming over the old City Hall, casting long shadows over the swing sets or the wildflowers, think that it wouldn’t be that pristine or beautiful if it weren’t for someone seeing a piece of litter and deciding something needed to be done about it

Just a few months prior to its opening, the park formerly known as City Park was a mess. No one needs reminding that Hurricane Katrina hit the area hard, and a lot was lost. But Carol Vegas Park was one of the first things in the area people came together to clean up and rebuild it. More than 500 volunteers and residents worked to clean up debris, lay the foundation and add the equipment donated by KaBoom!

And, in Carol Vegas’ name, the area was left a little brighter.

Coastal Camping

- story by LB Kovac, photos by Ellis Anderson

|

Raindrops on tent-flaps, roasted marshmallows. Swimming in pools, and camp stories with fellows. If these are a few of your favorite things, Hancock County is just the place for you.

In addition to the flourishing art scene, scenic beaches, and hopping downtown atmosphere, Hancock County boasts a thriving camping community. There's even a service that will rent you a camper, haul it to the campground you want and set it up for you. After the weekend, just pack up and drive away - Gulf Coast Camper Rentals will come and fetch it. Their motto is "we do the work, you enjoy the adventure." So whether you're blissful in a tent or adore luxe camping digs, when you've got a yearning for the great outdoors, check out one of these spots: |

Beach to Bayou

|

1150 S. Beach Blvd.

Waveland, MS

228-467-3822

The campground itself has over 200 campsites, both back-up and pull-thru spots. Campsites come with options for 30- and 50-amp connections, as well as Wi-Fi, cable, and a parking spot. There are dedicated primitive sites in the back of the campground for campers looking to pitch a tent. These sites don’t have fire circles or picnic tables, but they are spacious enough for multiple tents or extra equipment.

The best thing about the park, though, is its proximity to the gulf. Located on Beach Boulevard in Waveland, the Gulf of Mexico is quite literally across the street. If you know your travel plans ahead of time, you can reserve one of the park’s premium gulf-view spots, which give you amazing sunset views from the comfort of your camper. And white-sand beaches are just a short walk away!

The tradeoff for staying at such a big park is a bit of noise. There are dedicated quiet hours at Buccaneer State Park, but there are lots of campers, including families with young children, and some noise can't be helped.

8100 Texas Flat Rd.

Kiln, MS

228-467-1894

McLeod has about 50 campsites, with back-up and pull-thru sites available. Each site comes with a parking spot and picnic table, and slide-out campers can be accommodated. There’s also an on-site bathhouse with showers, a splash pad for the kids, and a playground.

Despite this campground’s seclusion, there’s still easy access to downtown Hancock County’s conveniences. Hollywood Casino, downtown Bay St. Louis, and Mississippi’s coastline are each just a 20-minute drive away.

8360 Lakeshore Dr.

Bay St. Louis, MS

228-466-0959

The campground park has a disc golf course for enthusiasts, the laundry rooms are free, and the staff have lots of recommendations for local eateries, bars, and family activities. During special holidays, there are free cookouts for the whole campground.

This campground is just three miles from the beach, and it’s even closer to several casinos. There are also plenty of restaurants and bars in downtown Bay St. Louis.

8012 Highway 90

Bay Saint Louis, MS

228-463-9670

This campground is centrally located for those who want to enjoy all of Hancock County’s features. Silver Slipper Casino, Hollywood Casino, the Stennis Space Center, and white sand beaches are all within a ten-minute drive.

Be aware that this campground only rents by the month. If you’re in Hancock County for a shorter stay, you might want to look at one of the other facilities.

These are just a few of the campgrounds in Hancock Country. Whether you’re just visiting the area or looking to call it home for a little while, there’s a campground just for you.

Off the Road, Along the Beach

- story by Laurie Johnson

|

Bicyclists and strollers will soon have another half-mile of coastline to enjoy on Hancock County’s popular beachfront walking/biking path.

On June 7, a ground-breaking ceremony signaled the official beginning of a $3- to $4-million project to extend the beach pedestrian and bike pathway from Lakeshore Drive to the Point Cadet by the Silver Slipper Casino. When the project is completed this fall, the county will boast nearly five miles of the paved off-the-road pathway. The grant funding for the project was secured for the county by the volunteers of the Hancock Chamber Greenways and Byways Committee. |

Beach to Bayou

|

Anderson says that when the new stretch is complete, only two gaps in the off-road trail will exist between the Bay Bridge and Bayou Caddy — a total distance of nearly nine miles.

One of those gaps is between the east side of Buccaneer State Park and Lakeshore Road, a distance of 2.25 miles. There’s only seawall there, with no beach to act as a bed for the concrete pathway. The Greenways committee is working toward eventually finding funding for an inland side segment of the path. Currently, pedestrians and bicyclists share the road with motor vehicles.

The other gap, about 1.15 miles, is between the east end of the paved pathway at the Washington Street Pier and the foot of the Bay Bridge, at Beach Boulevard and Highway 90. Although a sidewalk extends through that segment that passes through the heart of Old Town Bay St. Louis, building a dedicated bike path isn’t possible because of the seawall and high-density traffic and parking. But Anderson says that the committee has come up with an innovative way to improve cyclist safety in that section.

Anderson says the committee is applying for a grant with Transportation of America to fund a cultural signage project along that gap. The signage will actually be in the form of permanent pavement markings designed to raise awareness with motorists about sharing the road. These “road medallions” will be eye-catching and attractive, too, since they’ll be designed by local artists.

“This is the road we’ve got, so we’re going to have to make it work,” says Anderson. “And this pavement marking system will allow us to do raise awareness with motorists in a very artistic manner.”

Labat reports the group secured sponsorships from Hancock Bank, Keesler Federal Credit Union and Coast Electric Power Association to help their fund projects like the Christmas Bicycle Drive. Last year, the Bay Rollers donated 110 bicycles and helmets to local elementary school students.

In addition, members educate the recipients on how to operate bicycles around town safely. Kids learn the basic rules of the road and are taught not to get on the roads without an adult rider. Labat says they also encourage parents to continue bicycle safety education as they ride together.

Both Anderson and Labat want people to know that Mississippi law requires that motorists leave three feet of space between bicycles and their vehicle. Bike paths create a dedicated space for cyclists, but riders can use the roadways as long as they do so responsibly and safely. Signs are needed in many areas to remind everyone to share the road.

For those new to using bike paths, it’s important to know how to coexist safely with cars. Bicycles are allowed to take up the whole bike path lane and should always follow the roadway rules, just like a car.

Riders should never be on sidewalks dedicated for pedestrians. Cyclists should follow the same path of travel as cars; biking directly into oncoming traffic is a huge safety risk for the cyclist and motorists.

Labat says recreational athletes who enjoy cycling come to Bay St. Louis, Waveland and Lakeshore from across the U.S. because there are low speed roads with relatively low traffic. And the views are fantastic.

He notes, “If you have a beach cruiser and your intention is not to go very fast, the bike path is perfect for that.”

But road bikes are designed for speed, and Labat says cyclists on those bikes will want to share the road outside of the bike path and can do so safely and responsibly according to state law.

Labat says anyone can join their group by finding them on Facebook or contacting him directly at [email protected]. “There’s an old saying that you can’t be mad riding a bicycle.”

For more information about biking safety, see the website for the League of American Bicyclists.

Treasuring Turtles

- story by Ellis Anderson

|

Kent and Cynthia Miller’s large yard on Main Street in the Bay has become an unofficial turtle sanctuary. Cynthia often posts photos of her hard-shelled neighbors on Facebook with captions like “We found a new turtle in the yard today!”

The Millers apparently have an entire posse of turtles free-ranging on their property and have even named a few. Most are Gulf Coast Box Turtles.

According to Christy Milbourne of Central Mississippi Turtle Rescue, the species can live to well over 100 years and generally stay in the neighborhood in which they were hatched. That means some of the Millers' turtles might have lived on Main Street since the early 1900s.

|

Beach to Bayou

|

Christy and her husband Luke rehabilitate turtles that have had unfortunate encounters with canines, although most of their patients come from “road carnage.”

They work with veterinarians to nurse the turtles back to health, then release them back in the area where they were found. If their patient is permanently disabled, they care for them until a special needs home can be found.

But dogs and cars aren’t the only foes of turtles. Intentional harm by humans causes some turtle deaths and maimings.

A few misguided fishermen have been known to shoot turtles in the mistaken belief that they’re eating potential catches. Turtles can also be targets for both adults and kids who are practicing firearm skills. And there are the heartless drivers will purposely try to hit a turtle crossing a road.

“Sadly, we do see ones that have been hurt by malice,” says Christy.

Thus began a decade of intensive education, networking with turtle experts around the country, and the adoption of Booboo.

Booboo was a 17-year-old Redfoot Tortoise raised in a small tank by well-intentioned owners in Maryland. Due to a poor diet and his small environment, his shell was deformed enough to prevent use of his back legs. Surrendered to another rescue group, the Milbournes adopted Booboo in 2010. He became a beloved and spoiled member of their family.

According to a veterinarian specialist, Booboo wasn’t in pain, but would have a shorter lifespan. The predication came true, when, despite the pampering from the Milbournes, the tortoise passed away in 2012. His death solidified their dreams of dedicating even more of their time to turtle rescue.

Their website explains why it’s an awful idea to paint turtle shells (their shells are living tissue that will absorb toxins) or remove them from their natural habitats (they’ll spend the rest of their lives trying to get home). The rescue success story page makes for fascinating – and heartwarming – reading.

- Only stop when it’s safe for you and other drivers

- Never pick a turtle up by its tail (they feel pain and you might break their spinal cord)

- Always place it on the side of the road it was headed toward. If you place it back where it came from, the persistent critter will just try again.

For turtle emergencies, simply go to the website’s Contact Us page for instant advice.

“If you come across a wounded turtle, don’t assume it can’t live,” Christy says. “They’re incredibly tough. We work closely with a coast organization called Wild At Heart, so someone can help.”

The website also hosts an informative photo gallery, showing every type of turtle found in the state. According to Christy, the Mississippi coast is home to almost every one of them, 35 species.

Lucky for us – and the Millers.

The Least of Our Concerns

- by LB Kovac, photos by Charles Hubbard and Mozart Dedeaux

To prevent a repeat of last year's loss, it's going to take lots of residents willing to take action and encourage the Hancock Supervisors to allow Audubon to rope off the colony and post signs, like they do in Harrison County. Doing so helps an endangered species and can have a major positive impact on our Hancock County community. For instance, click here to read about the economic impact of birding in Toledo, Ohio.

|

Enjoy white sandy beaches? Relaxing afternoons ocean-side? Salty snacks and a cool breeze? Then you have a lot in common with the Sternula antillarum athalassos, or interior least tern.

You might have seen them on the beach before. Their black caps, grey underbellies, and bright yellow beaks make them stand out from other seaside birds like gulls, plovers, or pelicans. They also perform fantastic aerial feats, swooping and diving into the water as they search for food. |

Beach to Bayou

|

And something you probably don’t have in common with the least tern is their sleeping habits: least terns tend to nest and sleep on the ground. This leaves the birds, their eggs, and young chicks especially vulnerable to predators, like domestic cats, coyotes, and owls.

But the beaches of Harrison County have been a popular least tern destination in recent years; volunteers identified sixteen colonies in 2016.

This was good news for the endangered subspecies. As recently as 1985, the breeding population for all nesting sites in the entire United States had dropped as low as 3,000 pairs.

“Lots of people didn’t even know that they were there,” says Sarah Pacyna, Director of the Audubon Mississippi’s Coastal Bird Stewardship Program, an organization which coordinates monitoring efforts for coastal birds and stewards breeding population.

Their partial invisibility is due in part to the small size of their colonies, which rarely exceed 100 breeding pairs.

But the least terns knew we were there. See, least terns are rather finicky birds; they need peace and quiet in order to thrive. Pacyna says that, as a species, they are “especially susceptible to disturbance,” and the appearance of humans or domestic animals like cats and dogs near nesting sites can stress the birds out.

The least terns’ rather sudden appearance last year in Hancock County left Audubon’s team scrambling to protect the birds and give them ample room, and peace, to raise their young.

Audubon wasn’t able to secure permission to rope off the nesting area until late in the breeding season, and, unfortunately, some damage was done. Pacyna said that the Hancock colony ended up “failing:” some of the nests hatched chicks, but none of the chicks made it to adulthood.

But that doesn’t mean there is no hope for the future.

If possible, Pacyna will also coordinate volunteers to stand near the nesting sites, preventing beachgoers and pets from trampling nests or disturbing the colony. Volunteers can also provide valuable information on colony size and egg and chick production for least terns and other endangered coastal bird species.

Pacyna says that Audubon also has several contingency plans in place to make it easier for birds and humans to coexist on Hancock County’s beautiful beaches. If the terns decide to colonize near a popular stretch, her team can use decoys and clips of bird calls to lure them to a less-populated area.

You can do your part to protect these little birds. Pacyna says “be aware of your beach surroundings” when you’re out relaxing near the water. Keep an eye out for greenish, speckled eggs, which can be found in shallow indentations in the sand. And, if you do find a least tern nest, give the folks at Audubon a call.

This way, bird and human alike can enjoy the beach.

Read more about volunteer efforts here.

Celebrate the Gulf!

- by LB Kovac

Celebrate the Gulf is one of many outreach programs sponsored by the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources (MDMR). The festival is free and offers many fun opportunities for children to learn more about Mississippi’s diverse marine life.

And while the Gulf is home to millions of species of plants and animals, most children rarely see them except on the Discovery Channel or on their plates. At Celebrate the Gulf, they can get up close and personal with many of these species – including sharks, dolphins, and lionfish.

Melissa Scallan, MDMR’s director of public affairs, reports that last year’s festival was a big success, and this year’s event will be even bigger.

The exciting Raptor Roadshow – featuring birds of prey - schooner rides of the harbor, and coloring contests will be returning. Representatives from the Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) and the International Marine Mammal Studies (IMMS) will also be on hand to answer questions and lead activities.

Oysters are a valuable commodity to the Mississippi economy; last year, hundreds of thousands of bushels were harvested from gulf reefs, where they eventually ended up on plates across the United States. Oysters also play an important part in the state’s marine ecology - they attract blue crabs, starfish, and other sea creatures to the gulf’s waters.

It takes about two years for an American oyster to reach full “market” size – about 3 inches, in length. During those first two years of their lives, the little mollusks live in clusters, called “reefs,” on the seabed, where they filter the water for plankton, their favorite food.

It might seem like every restaurant has oysters on the menu, but they are not nearly as prevalent as they were fifty years ago, or even twenty years ago. Oyster harvests across the country are currently at 1% of historic levels.

Pollutants from natural disasters like the BP oil spill down severely depleted local reefs, and “aquatic hitchhiking” has introduced invasive species, like the Southern oyster drill, which eat the oysters at a rate faster than they can reproduce.

When people or objects like boats or buoys enter the water - even for a short time - plant life, small animals, and microscopic organisms make themselves at home on fabric, plastic, and other common materials. When the people go elsewhere or the objects are moved, they can take these “hitchhikers” with them, inadvertently spreading them to an area where they can harm plants or animals in another vicinity.

Luckily, as you’ll learn at the festival, aquatic hitchhiking is easily preventable. Rinsing off clothing, boats, and equipment at the dock or near the site can ensure that species native to the area stay there. You’ll do your part to protect the species currently in Mississippi waters.

For the past six years, Celebrate the Gulf has paired with Art in the Pass. Scallan says that the co-events provide the perfect opportunity for families to have fun and learn more about the world around them.

“People can come to one place [for Art in the Pass and Celebrate the Gulf]. There are lots of events for kids, and lots of opportunities for education,” she said.

Judy Reeves

- story by Pat Saik

A Chain Reaction

- by LB Kovac, photos/video by Ellis Anderson

|

It’s difficult to imagine a world without bicycles.

The two-wheeled vehicles can be found in cities around the world, but their history is short, relatively speaking: the grandfather of the bicycle, a wooden, two-wheeled German contraption called a draisine, didn’t make an appearance until 1817. And the word bicycle — from bi-, meaning “two,” and kyklos, meaning “wheel” — wasn’t used until the late 1860s. It has only taken two centuries for this mode of transportation to go from curio to staple. In 2016, more than 66 million people in the United States had ridden a bike in the last 12 months, per data from statistic-coagulator Statista. |

Beach To Bayou

|

Every Friday evening at 6:30 p.m., she and other area cyclists meet at 112 Court Street in Bay St. Louis, directly in front of the Daiquiri Shak. After a brief introduction, the cyclists leave Daiquiri Shak and go on one of three routes Angelo has mapped in the neighborhood.

“When the weather is good, we do everything,” she said.

Angelo, who lives Waveland, originally came up with the idea for Bay Bikers as a way to get to know people outside of her neighborhood. “I wanted to meet people in the community . . . and have a happy affair.”

“Everybody rides their bike in Bay Saint Louis,” says Angelo. Since October, she has been growing her group, and what started as a small collection of friends has now includes 30 or more riders every Friday night.

Angelo leads cyclists down one of many roads in the greater Bay Saint Louis area. Depending on the weather, Angelo says they might take a leisurely ride by bay or check out one of the community new restaurants or bars. There are lots of opportunities to explore even in a familiar place like your hometown.

The ride always ends at someplace “social.” Bars are always a good option — hence Angelo’s “adults only” policy — but Angelo maintains that the most important part of the ride is to learn something new about the community.

With that many people, big things are possible. EZ Riders recently did a charitable ride for a member with a cancer diagnosis. Over 200 cyclists attended, each donating $10 for the ride, and the proceeds provided a significant contribution to the member’s care.

Many clubs are using their cyclers for social change. Bikes Not Bombs, a Boston-based cycling club, raises money to support environmental causes. Riders in their annual bike-a-thon use creative means to find sponsors for their race, with the proceeds going to domestic and international charitable organizations and empowering community members to address local social and environmental issues.

Angelo hopes to do community-driven projects in the future. A recent can drive by members of Bay Bikers helped needy families in the area have a richer Thanksgiving celebration. They also supported local Veterans during the recent Veterans’ Day celebrations.

Angelo says that the club is “purely social,” with cyclists from “aspects of Bay Saint Louis welcome.” Angelo reports that, “We’re not out to compete. We’re just out to have a good time.”

Angelo says that the Bay Bikers are being accepted with open arms into the community. She reveals that “people wave” as they make their nightly rounds. And the colorful lights affixed to their wheels make them highly visible.

The club might be small now, but Angelo hopes that one day all of the Bay Bikers will light up the night.

If you’re in the Bay Saint Louis area and wish to join the Bay Bikers, look at the Bay Bikers Facebook page or email Karen Angelo directly at [email protected].

For the Birds

- story by LB Kovac

|

If you’ve been seeing fewer hummingbirds at your feeders this season, you’re not alone. Mitch Robinson reports that Mississippi residents have been inundating the Strawberry Plain Audubon Center with calls, frantic that their ruby-throated friends have been showing up less frequently this season.

Mississippi is home to ten species of hummingbird at any given time, including the shy Rufuous Hummingbird and the glittery Anna’s Hummingbird. And these little birds, along with many of Mississippi’s other native species, are difficult to track. The dwindling numbers “are representative of a larger uncertainty and the decreasing predictability of seasonal timings within our natural landscapes,” says Robinson. But fear not! There is something you can do to help. |

Beach to Bayou

|

At the time, natural conservation was still in its infancy, but that didn’t deter Chapman and 27 other “birders,” located in cities across the country, from traipsing off into the wilderness with binoculars in tow. During that first CBC, birders spotted specimens from more than 90 different species.

In the ensuing years, the information from the annual CBC has helped give researchers a “long term perspective” on bird populations. The Audubon Society website says that information collected during past CBCs has been used in over 200 peer-reviewed papers.

This year marks the 117th anniversary of Chapman’s first CBC. And national and international birders are gearing up for this year’s count, including in our own South Hancock County. On December 20, a group of local birders will be contributing to the census.

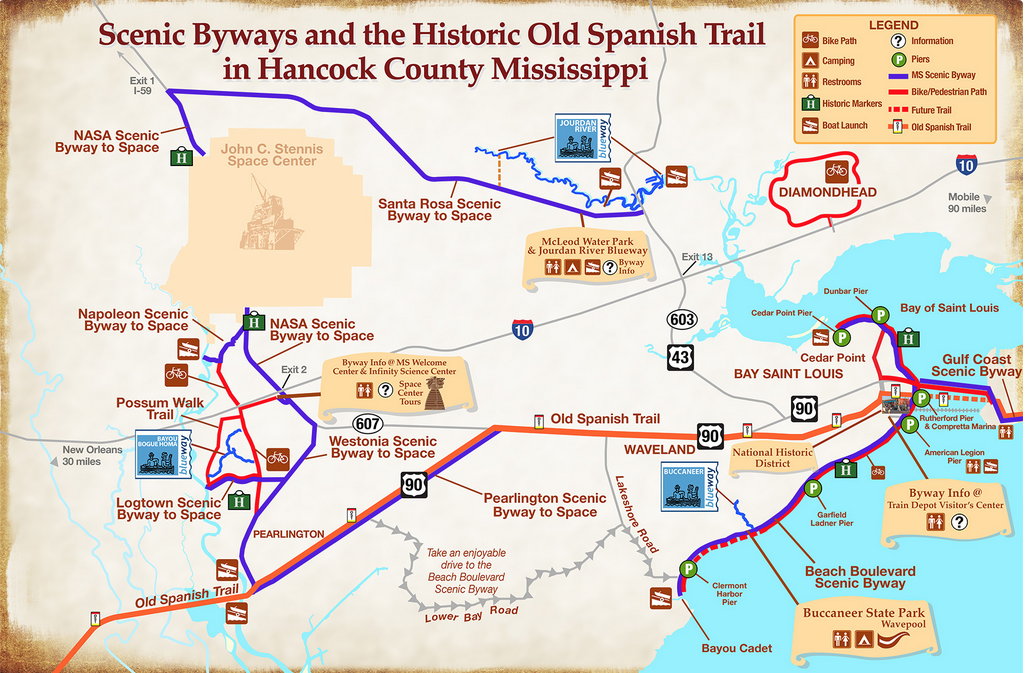

“The [South Hancock County] count covers a 15-mile diameter circle in Hancock County, from the south edge of Diamondhead West to the Logtown area, and south and west along the shore to Ansley and Heron Bay,” says Ned Boyajian, compiler for the South Hancock County Count (SHCC).

Hummingbirds aren’t the only species birders can expect to see during the count. According to Boyajian, individual parties can expect to see as many as 70 different bird species, with about 150 different species spotted throughout the day.

Additional counts are being conducted in neighboring counties and parishes, says Boyajian. The Jackson County count will take place on January 2, and Slidell and New Orleans have counts planned before the end of the year.

If you can’t come out to one of the counts, there are other ways you can get involved. If your home falls within one of the count areas, you can forego the excursion and watch (or listen for) the birds in your own backyard.

Boyajian recommends that these at-home birders confine their observations to a specific period of time. He also encourages keeping hanging bird feeders up, even during the colder months.

Some species of birds, like Anna’s Hummingbird, don’t have as varied of migration patterns as other species. Keeping a functioning feeder during the winter can help these birds tremendously. After all, hummingbirds do drink an average of five times their bodyweight in water every day!

And if you think just spotting birds isn’t very helpful, think again. According to the Audubon CBC website, the CBC is “one of only two large pools of information informing ornithologists and conservation biologists how the birds of the Americas are faring over time.”

By simply spotting birds with your binoculars or counting the hummingbirds at your feeder, you can help make a difference. From the CBC, Audubon and other organizations can “assess the health of bird populations and help guide conservation action.”

And those conservation efforts could, in turn, make it that much easier for other people to spot hummingbirds at their feeders next summer.

New Turkey Trot Tradition

- story by Ellis Anderson

|

Last year in Bay St. Louis, more than 500 people started Thanksgiving Day off with a new family tradition: running and walking through the historic district of Bay St. Louis.

This year, the 5th annual Fit First Turkey Trot 5k and Fun Run on Thanksgiving day 2016 is expected to draw even more participants. “It’s something fun – and healthy – to do as a family, before you sit down to eat 5000 calories,” says Helene Loiacano Johnson, laughing. She’s the local fitness guru who began the event five years ago. Helene says that several extended families participate every year. One Baton Rouge group that spends Thanksgiving in Bay St. Louis each year usually shows up with about 15 family members. |

Beach to Bayou

|

The event starts and ends on the grounds of the historic Depot in Bay St. Louis (1928 Depot Way, Bay St. Louis) on Thankgiving morning, November 24th. The cost for the 5k is $30 (pre-registered) and $35 (race day register) and $10 for the Fun Run (pre-register for either online now).

Those who haven’t preregistered online can do so at least one hour before start time. The 5k race starts at 8am, and the Fun Run at 8:45.

Both the certified 5k course and the one-mile Fun Run routes thread through the scenic historic district and along the beachfront before circling back to the Depot.

Awards will go to the First Overall Male and Female, First Overall Masters Male and Female and to the top three finishers in the age groups. Everyone who crosses the finish line gets an event t-shirt.

Helene said that Friends of the Animal Shelter will have a booth set up at the depot and will be able to accept additional donations of pet food, treats and toys – as well as monetary donations.

Last year, the Turkey Trot raised $1500 for the non-profit, which helps with their programs like free or low-cost spay and neuter. In 2015, Friends spayed or neutered 782 dogs and cats at no cost to their owners.

“It benefits a good cause, it brings families together and it’s healthy,” says Helene. “It’s a feel-great way to start off the holiday season.”

Helene notes that volunteers are always needed and welcome – even for simple tasks like handing out waters and medals. To help, call Helene at 228-342-6038.

Allison Anderson

- story by Pat Saik

It Feels Like Knowing A Secret

- story by Rheta Grimsley Johnson, photography by Martyn Lucas

Categories

All

15 Minutes

Across The Bridge

Aloha Diamondhead

Amtrak

Antiques

Architecture

Art

Arts Alive

Arts Locale

At Home In The Bay

Bay Bride

Bay Business

Bay Reads

Bay St. Louis

Beach To Bayou

Beach-to-bayou

Beautiful Things

Benefit

Big Buzz

Boats

Body+Mind+Spirit

Books

BSL Council Updates

BSL P&Z

Business

Business Buzz

Casting My Net

Civics

Coast Cuisine

Coast Lines Column

Day Tripping

Design

Diamondhead

DIY

Editors Notes

Education

Environment

Events

Fashion

Food

Friends Of The Animal Shelter

Good Neighbor

Grape Minds

Growing Up Downtown

Harbor Highlights

Health

History

Honor Roll

House And Garden

Legends And Legacies

Local Focal

Lodging

Mardi Gras

Mind+Body+Spirit

Mother Of Pearl

Murphy's Musical Notes

Music

Nature

Nature Notes

New Orleans

News

Noteworthy Women

Old Town Merchants

On The Shoofly

Parenting

Partner Spotlight

Pass Christian

Public Safety

Puppy-dog-tales

Rheta-grimsley-johnson

Science

Second Saturday

Shared History

Shared-history

Shelter-stars

Shoofly

Shore Thing Fishing Report

Sponsor Spotlight

Station-house-bsl

Talk Of The Town

The Eyes Have It

Tourism

Town Green

Town-green

Travel

Tying-the-knot

Video

Vintage-vignette

Vintage-vignette

Waveland

Weddings

Wellness

Window-shopping

Wines-and-dining

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

June 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

August 2014

January 2014

November 2013

August 2013

June 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

October 2012

September 2012

May 2012

March 2012

February 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

July 2011

June 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed