The author takes time to study the quietness of the forest and the unique qualities of its inhabitants.

- story by James Inabinet, PhD

Winged blue jays were doing bird-things: eating muscadine berries, building nests in early spring, picking aphids off of stems, and singing songs. Wiggling earthworms were doing earthworm things: tunneling just below the surface of the ground, eating leaves, feeding armadillos, squirming when encountering ants or sunlight.

Hopping frogs were doing frog things: sitting on lily pads, hunting insects, swimming, calling for a mate, and feeding snakes. Crawling fence lizards were doing lizard things: running over the ground, hunting, slipping tongues in and out of their mouths, performing push-ups to show off blue underbellies, feeding birds, digging under leaf mats, and remaining motionless when the shadow of a bird passes over.

Rooted red maples were doing maple things: limbs reaching toward the sun, growing tall in moist bottomlands, flowering and seeding in mid-winter, and feeding squirrels. The initial goal of the investigations was simply to make careful and detailed observations of anything that captured my interest. In the goldenrod field, for instance, I sought the unique character of goldenrod so as to understand its process of becoming, to understand how it became what it is. Not a form frozen in time, goldenrod grows and becomes, changing every day. Through detailed observations I noted how goldenrod expressed itself: basal rosette of fuzzy green leaves, long straight stems, robust yellow fall flowers. In the beginning, all goldenrods looked the same. Over time, the more I looked, the more I began to notice variations. I noticed that goldenrods in the field were usually small in stature, but large in flower while those in the forest tended to be large in stature and small in flower. Further investigations revealed individual differences. No two goldenrods were alike. I was eventually able to detect particulars for each one, a unique and individual character–though detecting that individual character was often difficult. After many forays watching animals, I noticed that after an organism’s needs were met, she would often sit idly, perhaps resting in a protected nook. A coyote near the bayou with a rabbit once panted under the low-lying limbs of wax myrtles. A frog-fed copperhead curled up on the creek bank in the shade of titi limbs. Satiated towhees sat on limbs, either singing or resting quietly. A finch left a bush half-full of berries and never returned - unless she slipped in and out without my noticing. It seemed that nearly all of the organisms I chose for careful study rested when not hunting or hiding or escaping. With no dire call to incessantly hunt and store food, enough seemed to be enough. In these ways and myriad others, I noticed that the characteristics of each organism amalgamated into a unique expression. Deathcaps of the forest floor displayed a unique sense of fungusness unlike that of puffballs. The squirrels of the canopy displayed a unique sense of squirrelness, an identity unexpressed by any other organism. Water oaks displayed a sense of oakness unique to their kind, an expression that I became so familiar with that I could eventually distinguish water oaks from others by gazing at twilight silhouettes from far away. I called each organism’s manner of being its identity. Each organism in the forest possessed a unique identity, unique as species, unique as individuals. The primary inclination of each individual seemed to be to express its unique identity as individual in its forest home. I longed to find out what humanness must be like in my forest home. I longed to find out my identity, to find out what Jamesness must be like if it were to be fully realized.

Hummingbirds, jewels of the Southern garden, are returning to our area after wintering in Central and South America. Find out how to welcome them home. - Story and photos by Dena Temple

Video (below) taken in Waveland in September, 2018 during the fall hummingbird migration. While 16 species of hummingbirds breed in the Northern Hemisphere, there is only one species that regularly inhabits our area, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The male is an iridescent green with a white underside and a red gorget (throat). As light is reflected off the gorget, it appears a fiery red; out of direct light, it appears dark. With wings that beat about 70 times per second, hummingbirds can indeed hover as well as fly backwards and upside down. They are interesting to watch and worthwhile to attract to your yard. There is no trick or special formula to attract hummingbirds. You just need to understand that all living things require three things to survive: food, shelter, and water. If you provide those things for hummingbirds, they will visit your yard, too. First, let’s talk food. Hummingbirds subsist on a combination of insects and the nectar from tubular-shaped flowers. While you probably won’t be able to set up an insect diner for the hummers, supplying nectar is as simple as putting out a hummingbird feeder. The feeder needn’t be fancy, or expensive; most wild bird stores and many garden centers have inexpensive feeders available. When selecting a feeder, be sure to choose one that is easy to clean, because you’ll be cleaning it often. My personal favorite is the Aspects Mini HummZinger (shown). It is extremely easy to clean and fill, and it comes with a lifetime warranty. Fill the feeder with a nectar solution made from one part sugar to four parts water. Contrary to popular belief, you don’t need to boil the mixture; just stir until the sugar dissolves. Mix only as much nectar as you need at that moment. And please, don’t use commercially available nectar formulations from the home center. They cost a fortune and include red dye and other unnecessary chemicals that may negatively affect your little lodgers. Hang your feeder in a semi-sheltered location such as under the eaves of the house, if possible, to keep rain water from contaminating the nectar. Clean your feeders often – at least once a week in cool weather, and more often in warmer weather. If the nectar looks cloudy or shows any mold growth, it’s past time to clean. The usual reason for lack of success in attracting hummers is setting out the feeder too late in the spring. Reports are already coming in from neighboring communities that the first hummers are back! Males return first to stake out breeding territories. If they find your feeder and the area looks safe, one may take up residence. In a week or two the females will return, looking for love – and an attractive territory. The right food plants can also make your yard more attractive to hummers. If you are planning on adding to your landscape, you might want to keep these plants in mind. (See list at the end of this article.) Shelter is the second requirement for attracting hummingbirds. If you have numerous trees and shrubs on your property, the birds have plenty of places to construct a nest or hide from predators. Water is the third requirement. A simple birdbath can be constructed from almost anything – a plate, a trash can lid (clean it first, please), a shallow plastic bowl. Again, be sure to keep the birdbath clean and shallowly filled. In our area, your first guest should appear in early March. You may not see regular activity at your hummingbird feeder for quite some time while the birds establish their territories. Once you start seeing the birds, note how territorial they are: One male will not allow another to use “his” feeder. If you hang more than one feeder, try to locate them so that they are not in direct view of each other, so one male cannot monopolize two feeders. Do not be surprised if your “guests” disappear several times during the summer season. When their favorite flowers bloom, they will feed only from the flowers, rejecting your finest offering. Don’t worry; they’ll be back. Also, breeding activity may keep them from being active in the garden. But just wait: if you provide them with suitable nesting habitat, you can enjoy watching the young hummers cavort around your hard all summer long, until they begin their southbound migration in September. Their games are enchanting to watch. As autumn approaches, you will see less and less of your guests as they begin their long migration to the tropics. You have helped make this trip possible by supplying them with the energy they need for this arduous trip. Do not be sad at their leaving; if all goes well, the same birds may reappear next year. Fall is the time to double up on your feeders; you will probably need to refill them daily to keep up with demand. Then, as hummers migrate south from the rest of North America, get ready for Invasion of the Migrants! An entire continent’s worth of hummers will stream past, pausing before making the arduous trip across the Gulf of Mexico. The amazing video above was taken at a Waveland feeder in mid-September. Keep your eyes open for rare migrating Western hummingbirds that occasionally lose their way and end up along the Gulf Coast. Hummingbirds make an attractive and interesting addition to any summer garden. It is well worth your while to invite them to spend their summer vacation at your “resort,” where they fascinate and captivate. All it takes is a few pennies’ worth of sugar – and a little patience.

A giddy newcomer and seasoned bird-watcher finds a wildlife bonanza here on the Gulf Coast.

- story by Dena Temple

Black Skimmer feeds by dragging its lower mandible through the water, trolling for fish.

“Tu-a-wee!” A flock of Eastern Bluebirds frolicked in the front yard.

Yes, we are birders. Bird-brains. Bird nerds! In fact, our fascination with feathered fauna helped drive our southern migration. And as birders, we weren’t looking for a home so much as a “habitat.” The pretty brick house on the tracks in Waveland fit the bill perfectly – lots of land bordered by dense woods, near a bayou. We signed the papers just before Thanksgiving, and by Turkey Day we were unpacking our binoculars and setting up feeding stations. We’re also a little competitive. And by “little,” I mean very. We compete with other bird nerds to see how many species of birds we can ID in our yards. We re-started our 2018 list when we moved to Waveland – and by the time the ball dropped on New Year’s Eve, our list stood at an astounding 52 species. In five weeks! While all seasons along the Coast provide excellent opportunities for wildlife-watching, perhaps the best kept secret is the diversity here in the winter.

Joining the resident species of the Gulf are thousands of birds that spend their summers breeding farther north. As lakes and bays freeze over, species that rely on aquatic habitat are forced to head south.

In addition, land birds that eat insects must migrate to follow the food source. So, while spring and fall offer the best variety because of the migratory birds passing along the Mississippi Flyway, winter birding delights savvy Gulf Coast residents who are “in the know.” Gulls, terns and particularly shorebirds flock to the Gulf beaches, much like our snowbirds do, for the Gulf’s agreeable climate and excellent dining. Everyone eats seafood along the Coast! Ducks, too, migrate south for the winter. Many only go as far as necessary to find unfrozen water, so they can find food. Some, however, make their way to our coastline and local ponds. Commonly seen from our beaches are Bufflehead, tiny black ducks with white bonnet-like caps, and Common Loons, looking drab in their “basic” winter plumage. One of my favorite places to look for birds is the Washington Street Pier in Bay St. Louis. What makes any location excellent for birds is habitat diversity, and this spot has it. Along the beach you’ll see lots of terns, gulls and shorebirds. Try to pick out the Willet, a large shorebird with drab, brown plumage – until he flies, revealing a distinctive and brilliant white wing stripe. Walking to the end of the pier, scan the water for the aforementioned ducks, along with Horned Grebes, which are common in the Sound in the winter, and Red-breasted Mergansers, ducks with a distinctive dagger-like bill. Next, scan the rocks at the pier for Ruddy Turnstone, a medium-sized shorebird with orange legs and an unusually patterned chest. Perhaps you’ll get lucky and spot a Purple Sandpiper in the rocks, a rare visitor from the North. While you’re out there, scan the distant skies for the beautiful white Northern Gannett, a large, graceful booby-like bird that nests on island cliffs but spends its entire winter over the water. Back on land, patiently check the dune grass for birds like Marsh Wren, sparrows and Scaly-breasted Munia, a non-native, pet-shop escapee that has been spotted here recently. There are many places along the Gulf Coast where beginners and pros alike can enjoy looking at, and learning about, birds. A great source is the Mississippi Coast Audubon Society, which hosts mostly free field trips to various locations in the area. Attending one of these trips is a great way to meet like-minded people, increase your local knowledge, and learn about conservation and habitat protection. If you’d rather strike out on your own, you can find information on the website for the Mississippi Coastal Birding Trail . The website identifies more than 40 prime birding locations in the six southern counties of Mississippi. It’s a great resource, and I’ll be working my way through that list myself. If you are the type who likes to volunteer, there are opportunities through both MCAS and the National Audubon Society for winter shorebird monitoring. Also coming up February 15-19 is the Great Backyard Bird Count, which encourages individuals to count birds in their own backyards (or a local park or hotspot), then report your findings online through a special website, www.birdsource.org. The event is held over Presidents Day weekend, which may give you an extra day to venture out and enjoy what our area has to offer.

A local naturalist and zen explorer experiments with ways to consider the world from another living creature's perspective - and discovers a new way of seeing.

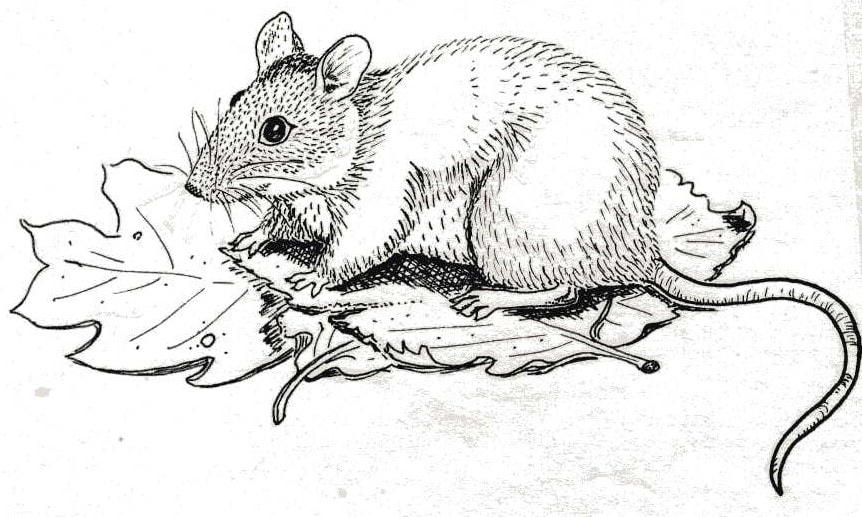

- by James Inabinet, PhD, illustrations by Margaret Inabinet

Mouse-seeing is an innocent way of seeing that begins with an empty mind, a “beginner’s mind,” one open to anything as Zen master Suzuki describes: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.”

To begin mouse-seeing, thinking is suspended through meditation or prayer. A quieted mind allows the “seer” to become more mindful of what’s happening right now, right here. With an empty mind one becomes like a hollow bone, ready to be filled with possibility. Several years ago, I ritually began my first journey into mouse-seeing in the goldenrod field. After sitting in meditation for a while, I dropped down and put my nose close to the ground like a mouse to see the field up close the way she would. I could see thickets of grass and goldenrod stems. With lowered head, I crawled for a while seeking mouse roads below the grass and goldenrod “canopy” and experience being in mouse habitat as I moved mouse-like through the field. After a half hour or so, I became bored and noticed that I had been thinking about home and work. I meditated and began again. Soon I stumbled onto what appeared to be a tiny trail. I slid onto my belly to look closer and discovered a mouse trail, a round hole through grass “trunks.” Opening back into the grass, the trail disappeared in shadow. Perhaps a tiny nest was back in there but I would never know. To get close enough to gaze at it would certainly destroy it.

I turned away and crawled towards the early sun. It struck me that humans are upright strangers that blithely walk through woods and fields as hawks, seeing from afar, from on high. We rarely see a mouse or even her signs and yet mice are legion, numbering in the thousands in this place alone. There on mouse roads they run, doing the doings of mice everyday unnoticed until someone gets down on her belly and looks with mouse eyes. Only then can mice and their way of being truly begin to exist for us.

As infants, we once possessed unmitigated body-knowing, as innocent as a mouse on her mouse-road – I only have to remember how to do it. Maybe I can return somehow to an infant’s sense of wonder, alert and curious – like a mouse. Intimate with her world, she sees clearly only what is right in front of her feeling, smelling nose. I moved closer to the stems of the grasses and goldenrods; I touched them with my face, feeling their roughness. Nose to the ground, I smelled the dark, damp earth where it was exposed. I listened closely while simultaneously smelling, feeling, looking. The mouse way is a doing way.

Energetically, I moved through the field, stopping only for brief moments. I alternately blurred my vision and then focused. In blurring, movement can be detected, vital in a mouse world that includes hawk shadows and snakes. With blurred images, one feels more than sees. Blurring interdicts thinking.

With closed eyes I laid down and focused on feelings. A surprisingly rough grass stem was touching my face. I tried to move into that feeling of roughness–without thinking. Moving my face to the side, I felt the mat of dry grass that covered the bare earth, again focusing on feelings. Moving forward a few inches I felt a grass stem on my forehead, focusing on feelings even as an image appeared, an image of what that grass might look like. I continued in this way for about an hour and had moved only about six feet. At the end of this experiment into mouse-seeing, I knew that particular feelings had arisen in me about the nature of the beings of the field, but I could not clearly recall them. It occurred to me that by purposefully suspending thinking, these feelings could not easily become thought and/or words. Something, though, was felt, something known, but I could not say exactly what it was. Even so, my relationship with this place deepened.

We rarely glimpse these nocturnal neighbors, but when we do, it's another reason to appreciate life on the coast. Find out what makes these critters good neighbors and ways you can help offset shrinking wildlife habitat.

- story by LB Kovac and Ellis Anderson

One of the charms of Bay St. Louis is that the humans coexist with an astonishing variety of wildlife. Bald eagles and foxes, owls and ospreys, turtles and pelicans, squirrels and geckos and possums and raccoons – to name only a few.

In fact, Mississippi is home to a substantial number of land mammals alone: 63. For reference, the Magnolia state beats Louisiana, the state closest in land size, by 11 species. Some of our furry neighbors, like the gray squirrel or the eastern cottontail, are a welcome sight no matter where you see them--be it on a nature trail or in your own backyard. Yet some people may be dubious about critters like foxes, raccoons and opossums, critters important to the delicate Mississippi ecosystem. Missy Dubuisson, owner of Vancleave-based wildlife rescue organization Wild at Heart, says that these are some of the animals her organization most often sees. She says, “we receive calls from federal, state and local law officers, and the general public” on a regular basis. Dubuisson has been rehabilitating animals since she was a little girl growing up in Pass Christian. Her love for wild animals, especially America’s only marsupial, has earned her the nickname “the Possum Queen.”

According to Dubuisson, some homeowners erroneously believe that opossums, raccoons and foxes are aggressive or carry infectious diseases like rabies. Both turn out to be myths.

“Many people see a possum and they think they’re going to attack. That’s not going to happen,” Dubuisson promises. She goes on to explain that they’ll only get aggressive if they’re on the defense. “Rightly so.” As for rabies? The state has been surprisingly rabies-free for the past fifty years. According to the Mississippi Department of Health, “Land animal rabies is rare in Mississippi. Since 1961, only a single case of land animal rabies (a feral cat in 2015) has been identified in our state.” Experts found that the cat had contracted rabies after being bitten, not by another land mammal, but by a bat. Possums, foxes and raccoons mostly live invisibly alongside humans in urban or semi-suburban areas like Bay-Waveland. All three creatures are dubbed opportunistic eaters. Possums feed on everything from roaches to slugs. Raccoons have a varied diet too, eating crawfish to berries. Much of a fox’s fare consists of invertebrates, like grasshoppers and caterpillars. Fortunately for their human neighbors, all three eagerly devour nuisance rodents. The fox, in particular, is valued for its superlative ability to catch rats and mice.

But as more lots and wooded areas are cleared for development along the coast, the habitat for native wildlife is rapidly disappearing. The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) has several programs in place to offset shrinking habitats by encouraging individuals and communities to create new ones.

Individuals can participate with the 40-year-old program, Garden for Wildlife. This step-by-step program guides homeowners in transforming an ordinary yard into a haven for birds and mammals that we love to watch. NWF even offers a certification once their checklist has been fulfilled. Signage celebrates the efforts and encourages neighbors to do likewise. Schools, college campuses and place of worship also have wildlife habitat programs, tailored specifically for them. Entire cities, like Bay St. Louis or Waveland, can apply to be official Wildlife Habitat Communities. In addition to practicing more sustainable, nature-friendly lifestyles that benefit both humans and animals, these communities receive positive national recognition. If Bay St. Louis or Waveland chose to participate, we’d be in good company: Disney’s Epcot Center is a showcase Habitat Community. As is the Denver Zoo. And in Maryland, “Baltimore Gas and Electric has created habitats along its power line rights of way.” For more information on participating, click on the links above. In the meantime savor another sighting:

Off the Road, Along the Beach

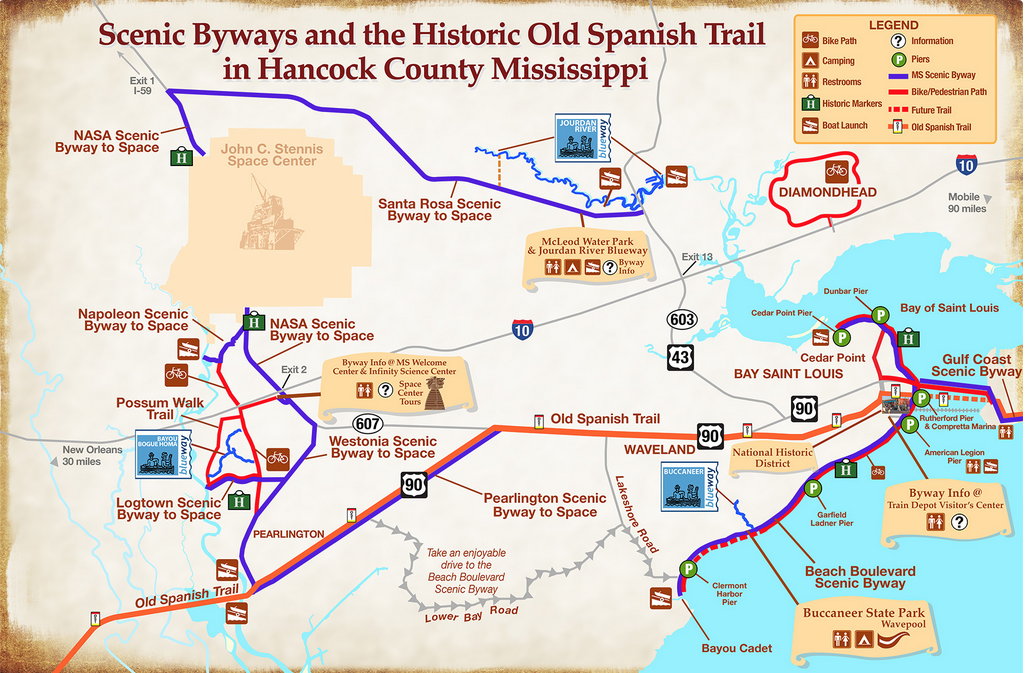

Another segment is being added to the popular beachfront walking/biking path, with plans in the works to make Hancock's coast road even more appealing to cyclists and pedestrians.

- story by Laurie Johnson

Allison Anderson of Unabridged Architecture is a longtime member of the Greenways and Scenic Byways Committee. She says that the new section of pathway helps move forward the committee’s long-range goals of offering a quality-of-life amenity for locals and creating a major visitor attraction.

Anderson says that when the new stretch is complete, only two gaps in the off-road trail will exist between the Bay Bridge and Bayou Caddy — a total distance of nearly nine miles. One of those gaps is between the east side of Buccaneer State Park and Lakeshore Road, a distance of 2.25 miles. There’s only seawall there, with no beach to act as a bed for the concrete pathway. The Greenways committee is working toward eventually finding funding for an inland side segment of the path. Currently, pedestrians and bicyclists share the road with motor vehicles. The other gap, about 1.15 miles, is between the east end of the paved pathway at the Washington Street Pier and the foot of the Bay Bridge, at Beach Boulevard and Highway 90. Although a sidewalk extends through that segment that passes through the heart of Old Town Bay St. Louis, building a dedicated bike path isn’t possible because of the seawall and high-density traffic and parking. But Anderson says that the committee has come up with an innovative way to improve cyclist safety in that section. Anderson says the committee is applying for a grant with Transportation of America to fund a cultural signage project along that gap. The signage will actually be in the form of permanent pavement markings designed to raise awareness with motorists about sharing the road. These “road medallions” will be eye-catching and attractive, too, since they’ll be designed by local artists. “This is the road we’ve got, so we’re going to have to make it work,” says Anderson. “And this pavement marking system will allow us to do raise awareness with motorists in a very artistic manner.”

In 2014, local cycling enthusiast Myron Labat formed a group called the Bay Roller Cycling Club. Members of the 11-member group of amateur cyclists are sharing their love of cycling and giving back to the community at the same time.

Labat reports the group secured sponsorships from Hancock Bank, Keesler Federal Credit Union and Coast Electric Power Association to help their fund projects like the Christmas Bicycle Drive. Last year, the Bay Rollers donated 110 bicycles and helmets to local elementary school students. In addition, members educate the recipients on how to operate bicycles around town safely. Kids learn the basic rules of the road and are taught not to get on the roads without an adult rider. Labat says they also encourage parents to continue bicycle safety education as they ride together. Both Anderson and Labat want people to know that Mississippi law requires that motorists leave three feet of space between bicycles and their vehicle. Bike paths create a dedicated space for cyclists, but riders can use the roadways as long as they do so responsibly and safely. Signs are needed in many areas to remind everyone to share the road. For those new to using bike paths, it’s important to know how to coexist safely with cars. Bicycles are allowed to take up the whole bike path lane and should always follow the roadway rules, just like a car. Riders should never be on sidewalks dedicated for pedestrians. Cyclists should follow the same path of travel as cars; biking directly into oncoming traffic is a huge safety risk for the cyclist and motorists. Labat says recreational athletes who enjoy cycling come to Bay St. Louis, Waveland and Lakeshore from across the U.S. because there are low speed roads with relatively low traffic. And the views are fantastic. He notes, “If you have a beach cruiser and your intention is not to go very fast, the bike path is perfect for that.” But road bikes are designed for speed, and Labat says cyclists on those bikes will want to share the road outside of the bike path and can do so safely and responsibly according to state law. Labat says anyone can join their group by finding them on Facebook or contacting him directly at mblabat1@gmail.com. “There’s an old saying that you can’t be mad riding a bicycle.” For more information about biking safety, see the website for the League of American Bicyclists. Ship Island Cruise

A hearty breakfast, a boat ride, a barrier island with a fort and a shore-side restaurant dinner: the perfect Mississippi summer day.

- story and photos by Karen Fineran I, Squirrel

Robbie MacDougal, Shetland Sheepdog and canine journalist - and longtime watcher of squirrels - takes a closer look at these frolicsome creatures, including Pete, President Truman's White House squirrel.

Next I read a tiny item that squirrels were once one of America’s favorite pets. One in particular, Pete the Squirrel, belonged to President Harry S. Truman.

When I researched squirrels as pets I found an article at atlasobscura.com that confirmed that squirrels indeed were popular pets. Mungo, for example, was a very special squirrel who belonged to Benjamin Franklin. When Mungo was killed by a dog, Franklin wrote, “Few squirrels were better accomplished, for he had a good education, had traveled far, and seen much of the world.” Katherine Grier’s book Pets in America noted that while colonial Americans kept many types of wild animals as pets, squirrels were the most popular. By the 1700s squirrels were the rage — they were kept in fine homes, clothed, fed well, and often even appeared in the ubiquitous family portraits. Eventually the fad of ownership lessened. They were, after all, wild animals, and behaved as such. Many states in the U.S. now have laws on the books prohibiting keeping squirrels at home. Squirrels still have a big place in our hearts, so there is National Squirrel Appreciation Day on January 21. To help you better appreciate these backyard critters, here are a few facts and thoughts on squirrels: Recognize these two fellas? They are the infamous Disney characters Chip and Dale.

To help you better appreciate these backyard critters, here are a few facts and thoughts on squirrels:

Recognize these two fellas? They are the infamous Disney characters Chip and Dale. Did you know that chipmunks are rodents and members of the family Sciuridae, just like grey squirrels? There are around 280 different species of squirrels, including gray squirrels, red squirrels, chipmunks, fox squirrels, marmots, and groundhogs. Betcha didn’t know there were so many. There are a lot of famous squirrel characters. See if you remember these characters compiled by ranker.com. To test your knowledge of squirrel trivia, check your answers to these questions at the National Wildlife Federation blog:

If you have children in your household, one of the best ways for them to learn about squirrel and other backyard habitats is using resources from the National Wildlife Federation. Ranger Rick is one of the best.

I want to be fair to my gentle readers who do not see squirrels and their relatives as benign, fun, lovely additions to the backyard environment. One of my neighbors sees them as enemies to be thwarted, and pesky rodents who steal birdseed from feeders. The World Wildlife Fund has some tricks for slowing down squirrels like weight-activated feeders, a feeding station just for the squirrels, and various baffles.

Keep in mind that squirrels are very resourceful, and that young squirrels learn from their mothers and grandmothers in attacking your feeder. Whatever you feel about squirrels, my advice is to get a good comfy chair and position it by the best window in the house and watch them perform. Love, Robbie Treasuring Turtles

A new rescue group in central Mississippi nurses wounded turtles back to health, as well as providing information for those wanting to foster suburban habitat for these fascinating creatures.

- story by Ellis Anderson

Christy says there are several things residents can do to make their yards turtle-friendly. Don’t use pesticides or herbicides, especially if you’ve seen turtles in your yard. Plant a garden – they provide great turtle habitat. Before mowing, check your yard for those who might be in harm's way. And keep watch if you have large dogs, which sometimes use turtles as chew toys.

Christy and her husband Luke rehabilitate turtles that have had unfortunate encounters with canines, although most of their patients come from “road carnage.” They work with veterinarians to nurse the turtles back to health, then release them back in the area where they were found. If their patient is permanently disabled, they care for them until a special needs home can be found. But dogs and cars aren’t the only foes of turtles. Intentional harm by humans causes some turtle deaths and maimings. A few misguided fishermen have been known to shoot turtles in the mistaken belief that they’re eating potential catches. Turtles can also be targets for both adults and kids who are practicing firearm skills. And there are the heartless drivers will purposely try to hit a turtle crossing a road. “Sadly, we do see ones that have been hurt by malice,” says Christy.

From Admirer to Rescuer

Christy came by her love of turtles as a child, appreciating their peaceful natures and the fact they carried their homes on their backs. She never lost the love. In 2006, when a neighbor found a three-legged turtle on a burn pile, he thought of the Milbournes – he’d seen turtle figurines in their house.

Thus began a decade of intensive education, networking with turtle experts around the country, and the adoption of Booboo. Booboo was a 17-year-old Redfoot Tortoise raised in a small tank by well-intentioned owners in Maryland. Due to a poor diet and his small environment, his shell was deformed enough to prevent use of his back legs. Surrendered to another rescue group, the Milbournes adopted Booboo in 2010. He became a beloved and spoiled member of their family. According to a veterinarian specialist, Booboo wasn’t in pain, but would have a shorter lifespan. The predication came true, when, despite the pampering from the Milbournes, the tortoise passed away in 2012. His death solidified their dreams of dedicating even more of their time to turtle rescue.

Both Milbournes still work full-time for the Mississippi Department of Transportation, but the non-profit they have formed works to raise awareness with people in addition to healing wounded turtles.

Their website explains why it’s an awful idea to paint turtle shells (their shells are living tissue that will absorb toxins) or remove them from their natural habitats (they’ll spend the rest of their lives trying to get home). The rescue success story page makes for fascinating – and heartwarming – reading.

Want to help a turtle cross a road? You’ll find complete instructions for that on the website as well:

For turtle emergencies, simply go to the website’s Contact Us page for instant advice. “If you come across a wounded turtle, don’t assume it can’t live,” Christy says. “They’re incredibly tough. We work closely with a coast organization called Wild At Heart, so someone can help.” The website also hosts an informative photo gallery, showing every type of turtle found in the state. According to Christy, the Mississippi coast is home to almost every one of them, 35 species. Lucky for us – and the Millers. Celebrate the Gulf!This beloved festival within a festival takes place during Art in the Pass each year, much to the delight of all who love the magical Gulf in our own backyard. - by LB Kovac Celebrate the Gulf Marine Education Festival takes place on Saturday, April 1st from 10am – 3pm, in Pass Christian’s War Memorial Park. The event is a popular part of Art in the Pass, a larger weekend festival that showcases work by artists from across the region. Celebrate the Gulf is one of many outreach programs sponsored by the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources (MDMR). The festival is free and offers many fun opportunities for children to learn more about Mississippi’s diverse marine life. Booths and activities will showcase plants like plankton and algae, fish like sharks and rockfish, and non-marine species that have a symbiotic relationship with the Gulf, including coastal birds. And while the Gulf is home to millions of species of plants and animals, most children rarely see them except on the Discovery Channel or on their plates. At Celebrate the Gulf, they can get up close and personal with many of these species – including sharks, dolphins, and lionfish. Melissa Scallan, MDMR’s director of public affairs, reports that last year’s festival was a big success, and this year’s event will be even bigger. The exciting Raptor Roadshow – featuring birds of prey - schooner rides of the harbor, and coloring contests will be returning. Representatives from the Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) and the International Marine Mammal Studies (IMMS) will also be on hand to answer questions and lead activities. Oysters will be one of the featured species at the festival this year. MDMR is responsible for 17 natural oyster reefs along the Mississippi Gulf Coast, safeguarding them for future generations. Oysters are a valuable commodity to the Mississippi economy; last year, hundreds of thousands of bushels were harvested from gulf reefs, where they eventually ended up on plates across the United States. Oysters also play an important part in the state’s marine ecology - they attract blue crabs, starfish, and other sea creatures to the gulf’s waters. It takes about two years for an American oyster to reach full “market” size – about 3 inches, in length. During those first two years of their lives, the little mollusks live in clusters, called “reefs,” on the seabed, where they filter the water for plankton, their favorite food. It might seem like every restaurant has oysters on the menu, but they are not nearly as prevalent as they were fifty years ago, or even twenty years ago. Oyster harvests across the country are currently at 1% of historic levels. Pollutants from natural disasters like the BP oil spill down severely depleted local reefs, and “aquatic hitchhiking” has introduced invasive species, like the Southern oyster drill, which eat the oysters at a rate faster than they can reproduce. “Aquatic hitchhiking” is a practice that is increasing in occurrence. Part of the festival’s mission is to empower attendees to protect the gulf on their own.

When people or objects like boats or buoys enter the water - even for a short time - plant life, small animals, and microscopic organisms make themselves at home on fabric, plastic, and other common materials. When the people go elsewhere or the objects are moved, they can take these “hitchhikers” with them, inadvertently spreading them to an area where they can harm plants or animals in another vicinity. Luckily, as you’ll learn at the festival, aquatic hitchhiking is easily preventable. Rinsing off clothing, boats, and equipment at the dock or near the site can ensure that species native to the area stay there. You’ll do your part to protect the species currently in Mississippi waters. For the past six years, Celebrate the Gulf has paired with Art in the Pass. Scallan says that the co-events provide the perfect opportunity for families to have fun and learn more about the world around them. “People can come to one place [for Art in the Pass and Celebrate the Gulf]. There are lots of events for kids, and lots of opportunities for education,” she said. Why I Fish

A great fishing experience doesn't depend on what you catch, according to this local fisher-woman and writer.

- by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson

By the time cool temps come back to the coast, I will have my launch tasks well practiced without bloodshed or dog paddling in the harbor. Of course, I will have forgotten everything I have learned by next April, when the specks start running again.

Back to Saturday’s fishing. After a period of short strikes to the lures but no bites, we started to move west, testing the reefs until we finally turned north at Henderson Point to the mouth of Bay St. Louis. Still no bites, which remains the mystery of fishing. The fishing forecasts on the Internet need to have their programming checked. I think I’ve lost 75 hours of sleep this year due to those forecasts. My catches this year have been legal specks (keepers), juvenile specks (toss back), and monster reds. I can hook these great grey beasts with the single spot on each side of their tails, but I leave it to my taller and more-experienced husband to land the critter. Let’s face it: there is a better chance of my losing the prize. Would you take a chance on possibly landing a big fish or be certain that courtbouillion was on the menu that night? Hand off that pole to the wrangler.

We wade fish, too, out of Pass Christian. In the low light of dawn, we throw out our first lines as we walk the edge of the water. Vehicle traffic on Highway 90 begins to pick up as we glimpse sunlight behind the surface clouds. Each sunrise is special — a peacock’s tail of colors or a study in cloud formations. When the colors of morning fade, the sunglasses go on and the real work begins.

The husband tells me that I have my reel on the wrong side of the rod. Trust me; if it were on the left, I would spend most of the day reeling in my first cast. I am a dyed-in-the-wool righty, and my left hand serves little purpose other than to display jewels and type the keys on the left side. So, what is the best thing about going fishing? It is listening to my best buddy relate special fishing stories from his youth. The best one from 1974 is the one when he and his older sister were out fishing under the train trestle. Imagine two teenagers, listening to WRNO music radio, and just enjoying the day. The trestle rumbled, announcing the approach of the regularly scheduled train. The kids waved up to the train and its familiar engineer. A surprise that warm day, the engineer tossed something down to their Boston Whaler. The goods missed the boat, so my future husband jumped in the water and retrieved two Baby Ruth candy bars. I suppose that these days he keeps looking for more prizes to capture out of the water. Who would trade a day on land for the chance to hear a story like that? Biking Beach Boulevard

This month, ride along with local wildlife photographer Chris Christofferson as she bikes Hancock County's 12 mile beach road, starting at Cedar Point and ending at Bayou Caddy - story and photos by P. Chris Christofferson

Cedar Point boat launch at the end of North Beach Blvd is public and leased by Hancock County from the Hollywood Casino, which sits with its golf course across from the launch inlet. It has two launch ramps, a covered bench area, two port-o-lets (but no water spigots), lights on from dusk to dawn, a small fishing deck and a surrounding bay wall. It's the perfect place for fishing the bay, since it has a generous parking area. A peaceful place to sit and observe beauty of the north bay and mouth of the Jordan river and be expectantly watched by a few egrets and laughing gulls, waiting on treats.

From the boat launch to the intersection of North Beach Blvd and Hwy 90 at 2.9 miles, there is only street biking, but the bay wall supports walkers and fishermen to the Bay-Waveland Yacht Club at 2.5 miles. Speed restriction is 25 mph which seemed well regarded by the locals. .4 Miles

Wetlands from the boat launch to the first group of homes, several of these being rentals with private piers. As I leaned on my handlebars for a few minutes, absorbing its pristine, serene beauty, many birds flitted through singing and calling. I recognized a laughing gull, Brewer’s blackbirds, cardinals, red-winged blackbirds, Carolina chickadees and a red-headed woodpecker, amid other bird songs I couldn’t identify. What a satisfying beginning for this adventure!

1.2 Miles

1.5 - 2.3 Miles

I had never noticed before, but there are several ladders into the water for easy climbing back onto the wall. Given no beach from the boat launch until Bay Waveland Yacht Club, it’s convenient.

2.5 Miles

Bay Waveland Yacht Club. A private yacht club, started in 1896 and beautifully rebuilt.

2.5 - 2.8 Miles

The only beach front on this section of North Beach Blvd is between the yacht club and Hwy 90, but it is all privately owned by the residents across the street.

2.8 Miles

North Beach Blvd crosses Hwy 90 at the St. Louis Bay Bridge. The fabulously rebuilt bridge’s lit biking and walking lane provides a spectacular view of the bay with parking available across the street at its foot.

3.1 Miles

From the bridge to this point, which is .4 mile, the beautifully manicured white sand beach behind the privately owned fenced gazebo is directly accessible. But, then, at the beginning of the tiered flood wall there is cable running the length of the walkway at the top preventing one from going down the stairs to the beach all the way into Bay St. Louis behind The Blind Tiger. This morning, the first flock of birds I saw were about 20 laughing gulls. Strange to me, that only a very few great blue herons and egrets were seen to this point and no pelicans; but lots of songbirds on the wetland and house side of the road.

3.5 Miles

Jimmy Rutherford Pier in the Bay St. Louis marina is the longest of the five public piers on the beach road and is brand new, with overhead lights. It is very conveniently connected to a ramp for short-term boat tie ups. It has two covered sections with benches, but doesn’t allow bait-cutting or net fishing and has no water spigots. The marina dock offers restrooms.

The newly opened Bay St. Louis Harbor has permanent, as well as transient docking available with full amenities and a huge parking lot, usable for festivals as well. Interestingly, here is no boat launch. Here on North Beach Blvd, the Bay Town Inn tree (which saved three lives during Hurricane Katrina) sculpted into angels, is a delightful spot to lounge on the bench at its base and watch the bustling street and bay action. 3.6 Miles

From Cedar Point boat launch to Main Street Bay St. Louis. The bay side has restaurants and private businesses furiously being erected. Bay St. Louis was recently reported as the fastest growing town on the coast. If you’re still with me, and want to use Main Street as mile marker zero, instead of Cedar Point, obviously just subtract 3.6 from the following distances.

3.7 - 3.9 Miles

Our Lady Academy, Our Lady of the Gulf Catholic Church and St. Stanislaus College. The name of the beach road changes from North Beach Blvd to South Beach Blvd at the intersection of Main Street. A tiered floodwall with sidewalk runs from the railroad tracks to the newly rebuilt Washington Street Pier and pavilion.

4.1 Miles

Washington St. Pier and Pavilion is a very popular recreation center of Hancock County which supports a double boat launch and fishing pier as well as a pavilion (available for rentals), generous parking, 200 feet white pure sand beach and bathrooms. Friday morning, a van was in the parking lot offering kayaks for rent.

The rebuilt Washington Street Pier seems to be the most basic of all five public piers along the beach road, with no coverings and no water spigots. However, there are rail lights on dusk to dawn and handicap accessibility. I saw about 20 laughing gulls, one great blue heron, two egrets and on the rocks at the beach about 60 pigeons, lolling in the sun. In the marsh grass, there was a red-winged blackbird and, I think, an Eastern kingbird.

From Washington Street in Bay St. Louis into Waveland for 4.5 miles , there is a remarkably fabulous, approximately 200 feet wide, stretch of a man-made white sand beach with protective sand dunes and the first biking path as well as a walking path, well-groomed by the county. Garbage cans are intermittently placed, which, aggravatingly, seem too often ignored by day-beachers. Car parking, on the land side is intermittently available (with care to not get stuck if the sand is too deep or wet). This is a gorgeous stretch which we can be so very proud of its rebuilding even better 10 years out!

At the Waveland/Bay St. Louis city line, the name of the road changes BACK to South Beach Blvd. Both cities have a South Beach and North Beach Boulevard - even though it's all the same road. 4.3 Miles

What struck me was that in the area of Ballantine to St Charles, the sand dunes are higher than the bike path so there is always, but particularly with a stiff breeze, build up over the path. I had to be careful my bike tires didn’t slide, with me landing on my tusch.

6.1 Miles

Nicholson Ave is a main road to the beach from the Hwy 603 and 607 intersection. At the corner of Nicholson on the hill of a private, Katrina empty lot is a swing which withstood Katrina and is often the site for wedding photos or just folks relaxing, since they're able to gaze all the way to the ship channels in the bay. Unfortunately for beachers, for a couple of hundred yards on either side of Nicholson, the sand is full of broken oyster shells which make it so very uncomfortable to sit, painful to walk without shoes, and very unsightly, compared to the pristine sand to this point and after the drainage canal at Sarah’s Lane at 6.4 miles.

According to Lisa Cowand, president of the Hancock Board of Supervisors, they are aware of this problem and want it cleaned. But, that area of the beach (being a corp of engineer initial project) poses difficult logistics, which she says is taking time to rectify. The reddish-brown color of the water flowing into the bay at the Sarah’s Lane drainage canal is from iron ore deposits in the soil, and not a dangerous discharge to beach walkers, again, according to Lisa Cowand. 6.8 Miles

Garfield Ladner Memorial Pier. I hope its revival will be the gem needed to jump-start Waveland development. It recently reopened in June. To me, it has it all. A long, wide pier with overhead lights on from dusk to dawn, six covered stations with benches, lights directed into the water for night fishing, plenty of parking and porto-o-lets planned.

This is the only public pier on the beach road to have water spigots interspersed on the pier,which I think is a huge amenity. Before it closed because of Hurricane Isaac damage, it required a fee, but none is to be required at present. There are even six sand volleyball courts and a wide beach. Even early afternoon Friday there were a lot of beachers. A snowball truck was there and very popular that hot afternoon. The City of Waveland Veterans Memorial park is as poignant and beautiful as any I’ve ever seen. At the water’s edge by the volleyball courts, I saw four peeps and a sanderling, for the first time, with a few laughing gulls.Destination America-Red White and You is sponsoring a spectacular celebration at the pier for the 4th of July with rides, food and awesome fireworks. It couldn’t be a better introduction to the community of the newly renovated pier! 6.9 Miles

Coleman Ave is Waveland’s main street, all new construction post-Katrina. North Beach Blvd becomes South Beach Blvd at this intersection. By the time I reached here, about 2:30 PM, my suntan lotion was sweated off and, out of bottled water, I was really thirsty. Port-of-Call General Store on Coleman is the perfect beach general store. Soft drinks, beer, ice, beach food, fresh fruit, t-shirts, first aid including suntan lotion, beach toys, towels and lots more. It is invaluable as the only general store close to the beach the entire 11.7 of beach road. It even rents bicycles. Refreshed, I was back on my bike to finish this survey of the beach road’s delectable offerings.

7.2 Miles

St. Clare Catholic Church at the intersection of South Beach Blvd with Vacation Lane is the 3rd and last church on the beach road, all 3 having been rebuilt after Katrina with current robust congregations.

8.6 Miles

This ends the man-made, extensive sandy beach at a private pier with the beginning of a bay wall, satisfactory for fishing and walking, but bike riding is relegated to the road the rest of the way to Silver Slipper Casino at the 11.7 mile mark. Touring RVs of all sizes on their way to Buccaneer State Park and Silver Slipper crowd other bicyclists with few honoring the 25mph speed limit. Encounters can get tense.

9.4 Miles

Buccaneer State Park. Camping, water slides and pools and recreation pavilions with full bathrooms, all for a fee, make this a well-maintained, deservedly praised and very popular summer family destination.

9.7 Miles

Waveland City limits and beginning of Clermont Harbor. The wetlands with teeming songbirds, egrets and the occasional great blue heron are unspoiled and magical. From here to the Clermont Harbor fishing pier at 10.4 mile, there’s a couple of outcropping, small, untended beaches and very intermittent roadside parking.

10.4 Miles

Clermont Harbor Pier, just past Bordage street, is public with 14 covered units and benches, side rail lighting on from dusk to dawn, but no water spigots or port-o-lets and limited roadside parking. However, with Buccaneer State Park and the Silver Slipper Casino nearby, it seemed a very popular and congenial place on Friday afternoon.

10.8 Miles

This begins the man-made and beautifully maintained white sand beach to the Silver Slipper at 11.7 miles. This stretch also supports a casino RV park in between stretches of gorgeous, untouched wetlands. Road traffic is heavy on weekend afternoons, so bikers need to be attentive, stick close to the side of the road and beware of vehicles exceeding the 26 MPH speed limit.

11.7 Miles

Silver Slipper Casino - the end! A lovely hotel has just been added to the casino and first-class restaurant as a confident investment in the future of Hancock county. I ducked into the air-conditioned casino lobby (shock) at 4:15PM, weary, dirty, sunburned and sweaty, to be met by the cacophonous sounds of scores of slot machines and a collage of bright color. The juxtaposition was intense after a leisurely day of pedaling to the rhythm of soft breeze whispers, song birds, cricket chirps, frog calls, and lapping waves and visions of picture-perfect beach beauty, shore birds foraging, shrimpers on the horizon, fishermen on piers and walls and a clear blue sky. Obviously, the Bay/Waveland beach road attracts all personalities, exactly as it should!

The intrepid community investment in the beach road, both in conservation and development, is a resounding success ten years after disaster ferociously struck.

We should be proud, my neighbors, as we stay diligent protecting this little piece of heaven. Lisa Cowand informs me upgrades are in the future, but I can only hope none of the rustic charm is lost in the process and it is only enhanced.

A honeybee hive on the rooftop of an Old Town restaurant? Yep! Find out how hive hosting is good for the community, the food chain and makes for good family fun!

- photos and story by Ellis Anderson Bee Here Now! The New Trend in Hive Hosting

That’s not the case with many hives across the country today. Josh says that nearly a third of bee hives in the U.S. die off each year. Pesticides, bee predators and fungi are chief among the identified culprits, but the high rate of mortality remains somewhat of a mystery.

The high rate of loss makes beekeeping a risky profession these days, but Josh Reeves is undeterred. He and his father-in-law, Jim Huk, began their company just last year. J&J Bees and Trees focuses on raising citrus trees and honeybees. The two currently own and manage about 25 hives. They’re hoping to double the number of hives each year and eventually provide local honey on a small scale. One arm of their business is neighborhood hive hosting. Most of the country’s 2.4 million domesticated bee colonies are utilized in agriculture for pollination purposes. Bees pollinate one out of every three bites of food we eat, making a $14.6 billion impact on agricultural harvests. But it’s a growing trend for homeowners in cities or suburbs to host bee hives. Here’s how it works. For a set annual fee, Josh Reeves will set up and maintain a honeybee hive at someone’s home or business. The property doesn’t even have to be large or rural, it simply has to be bee-friendly. The Starfish Café is a case in point. It’s in the middle of Old Town, and the hive, since it’s mounted on the roof, takes up no yard space.  Find J&J's Bees & Trees on Facebook or call (228) 363-3490 Find J&J's Bees & Trees on Facebook or call (228) 363-3490

The hive hosters benefit in several ways. They receive a portion of the honey harvested each year (although there’s not much of a harvest the first year while the hive is getting established). Hosters don’t have to care for the hives. Josh checks in periodically to make sure all is well. The host family has the satisfaction that they’re giving pollinators a place to call home – and increasing the production of their neighbors' vegetable gardens. Or their own. Di Fillhart, owner of the Starfish Café, noted a huge uptick in the production of the restaurant’s vegetable garden since the bees moved in.

Josh’s passion for bees began after he retired from the military and he and his wife, Jinny, bought a small farm in Ohio. The couple raised goats, chickens and pigs, in addition to raising much of their own food. In nearby Medina, Ohio, the A.I. Root company offered beekeeping workshops and Josh signed up for a few classes. Root is a candle company now, but used to be one of the country’s foremost suppliers of bee-keeping equipment and is still involved by providing educational resources for beekeepers. Reeves was smitten with the hard-working insects and kept hives for the next five years. When the family relocated back to the Mississippi coast in 2014, they decided to create a company based on their passions and their values. Their mission statement (below) expresses the goals of the Reeves’s lives and their company. They want to bring families together. They want to educate the community about bees. They want to introduce others to what Josh calls the Gee Whiz factor, the joy and amazement that comes from living in harmony with nature.

The day the Cleaver photographs Josh checking on the Starfish hive, he begins by lighting some straw in a special smoker device. It looks sort of like a little watering can with bellows. Once the straw is smoking, he directs a few puffs of it into the hive from the bottom, where the bees are coming and going.

It doesn’t take much to calm the bees. He waits a few minutes, then moves calmly to open the hive from the top. He’s dressed only in jeans and a t-shirt, not the bee-keeping space suit that’s usually seen in cartoons and movies. Once he’s opened up the hive, he begins pulling out the vertically stacked trays that the bees build their honeycombs on. He holds them by the wooden edges since both faces of the trays are covered by bees busily stuffing nectar into little cells. Reeves explains that since the queen dictates the temperament of the hive, “gentle” ones - those who don’t seem to be unduly angered by human interaction - are bred. That’s why most domesticated honey bees are not as aggressive as legend suggests. After he makes sure the queen is thriving and no pests have crashed the party (mites and fungi are the main threats in this part of the country), he reassembles the hive. A few minutes later, the beekeeper climbs down from the roof without a single sting to mark the experience.

In the future, Reeves is hoping to make the hive openings at the Starfish educational events open to anyone who wants to learn more about honeybees (contact the Starfish to find out Reeve’s next scheduled visit). It’s the perfect family summertime outing, sure to keep kids “buzzing” for days. Since the Starfish hive is on the roof, observers have a great view from below. It’s safely out of angry bee distance in case someone’s afraid the queen might be having a grumpy day.

The Starfish hive is just one of several J&J hives hosted in the area. The word’s getting out and more people are calling Josh daily to inquire about getting into the program. Why the surge in interest? “I’ve talked to so many older people whose father or grandfather raised bees,” says Josh. “They remember it from their childhood. Of course the younger kids haven’t had that experience, but what kid doesn’t like a bug? When you can take a male bee – the kind without a stinger - and put it in a child’s hands, it’s neat to see what happens. It’s really easy to bridge a generational gap with honey bees.”

J&J Bee’s and Trees is more than just honey. It is impacting the community through education, family and making our environment more vibrant and wholesome. It starts in your backyard and spreads throughout the world.

Find J&J's Bees & Trees on Facebook or call (228) 363-3490 J&J's Mission Statement

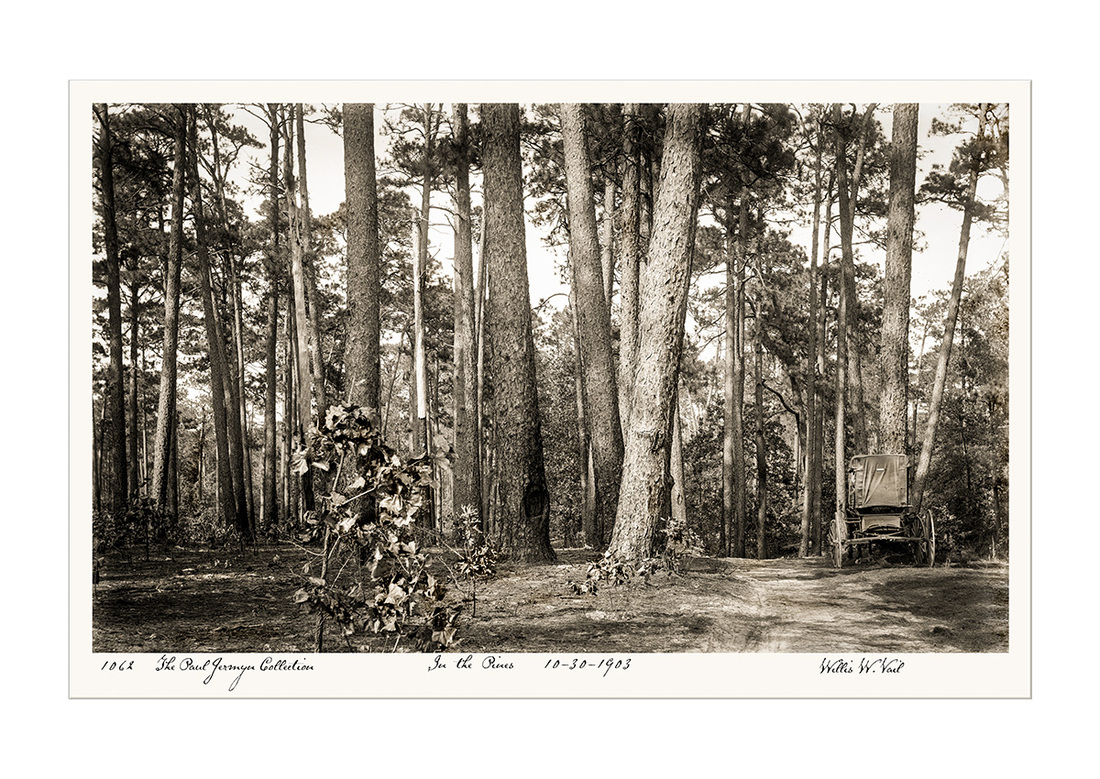

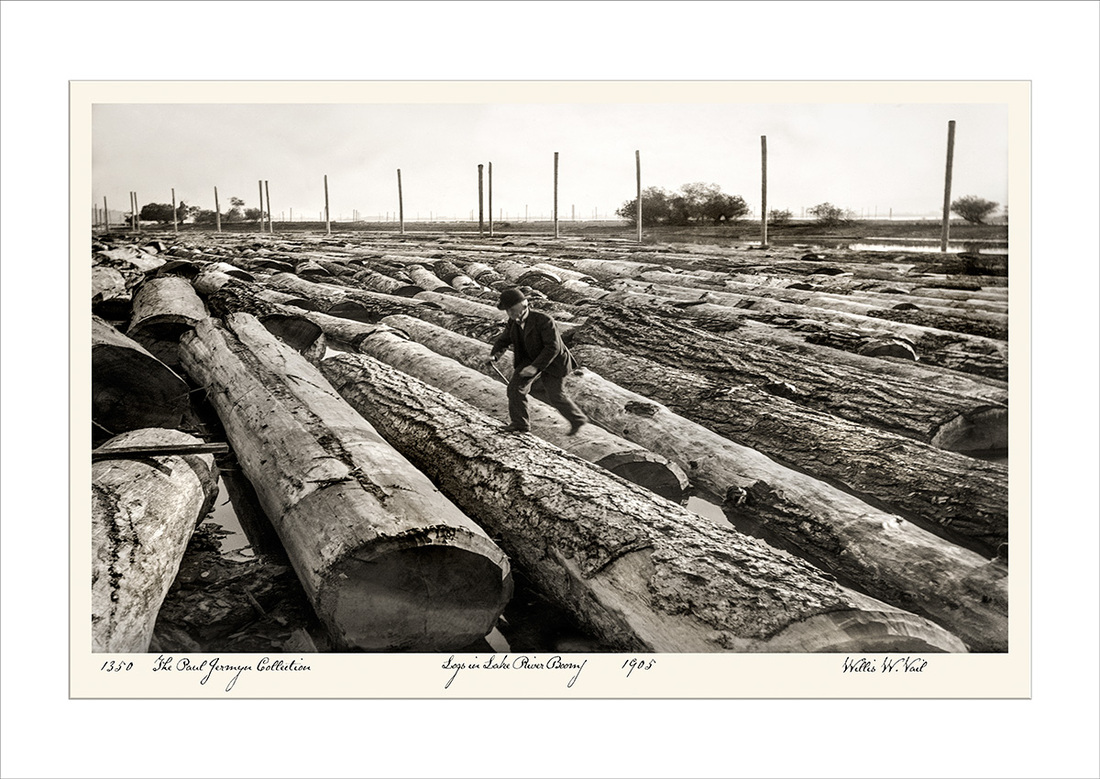

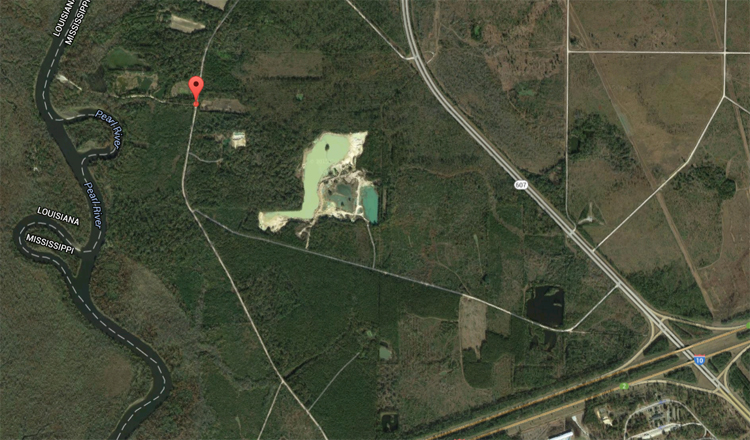

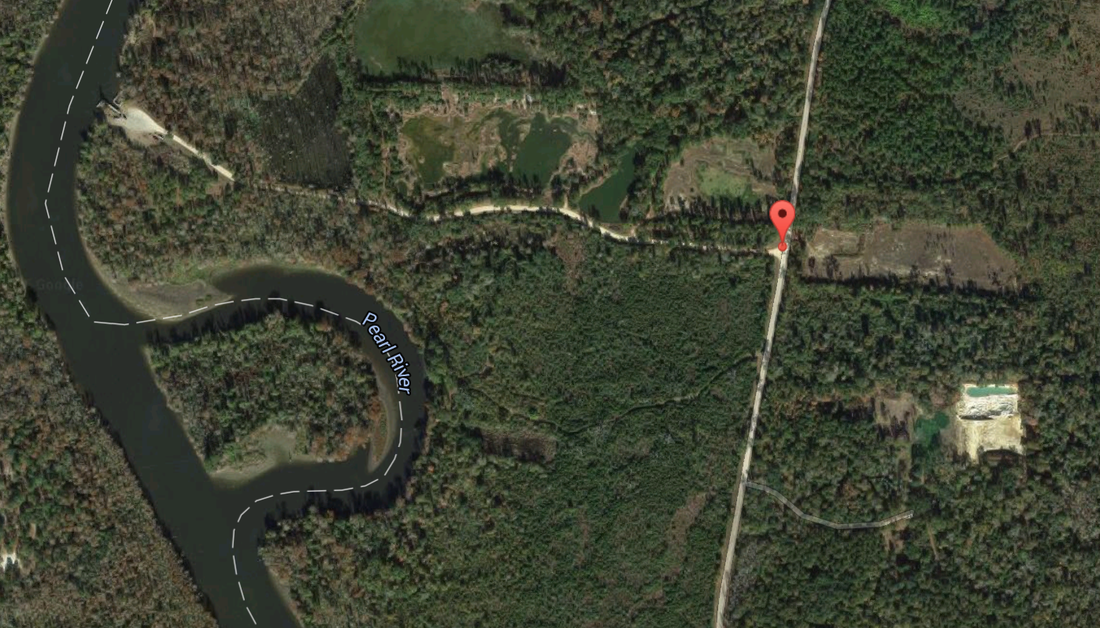

The Mississippi Gulf Coast Birding Trail - Napoleon by the Pearl Just miles from Bay St. Louis, you can step into another world - and another time - at this isolated spot on the Mississippi birding trail. - by Ellis Anderson photography by P. Chris Christofferson and Ellis Anderson

The lightening sky revealed a heavy fog as I drove down to Waveland to pick up my partner in this morning adventure, photographer P. Chris Christofferson. She brought along her own camera equipment, mosquito repellent, several bottles of water and a picnic lunch. She also gifted me with a nifty fluorescent orange vest. While it wasn’t hunting season, we didn’t want to be mistaken for wild boars by anyone else we might come across while trekking through the Hancock County wetlands. The two of us would be stalking birds, armed with cameras rather than guns. As another safety precaution, we'd also told our husbands where we were going, so in case we went missing for a few days, they might come and look for us. We were headed to Napoleon (or Napoleonville, as it’s called on the Mississippi Gulf Coast Birding Trail map), the site of a centuries-old historic community on the east bank of the Pearl River. Its residents were resettled when Stennis Space Center was constructed in the 1960s, so now it’s officially “extinct.” But 14,000 years or so before this place was named after a French emperor, Native American civilizations made this magical land their home, hunting camels and tigers and mastadons. Later cultures built earthworks and mounds that have survived thousands of years. The incredible pine forests that sheltered eons of animals and humans – ones that must have rivaled the west coast redwoods - did not survive. They were completely razed by short-sighted lumber barons in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. “Completely” is not hyperbole in this case. To my knowledge, there’s not a stand of them remaining on the entire Mississippi coast (e-mail me if you know of one!). Yet the landscape near the Pearl still oozes with a primordial atmosphere. One wouldn’t be awfully surprised if a bison came lumbering through the underbrush. Chris and I were using the new Mississippi Coast birding trail on-line guide. The Napoleonville site is one of the places recommended for year round observation of several “sought after species.” The sighting of one of these birds scores major points in the serious bird-watching world. Both Chris and I are novice bird-watchers, so approached the morning’s expedition with an open mind. Good thing. While we didn’t succeed in getting any spectacular photos of birds, we both reveled in having a good excuse to go tromping around in the woods, immersing ourselves in the natural world and for that morning at least, becoming just two more creatures in a forest swarming with life. The stress of our everyday lives melted away. We found ourselves in a different world, one where deadlines and obligations became meaningless. Napoleon is part of the Mississippi Gulf Coast Birding Trail and a highlight of the the Hancock County Scenic Byways. Here’s a quick run-down on what to expect at Napoleon if you’d like to take your own birding expedition. Head north on Hwy 607, past the 1-10 Exit 2 interchange, toward the Stennis Space Center complex gate. You’ll see a brown sign pointing to the Napoleon turnoff, turn left there. Eventually, you’ll come to sign pointing to another turn-off to your right, onto a gravel/dirt road. The times I’ve been out there, the road has been in pretty good condition, so most cars ought to be able to handle it with ease. Slideshow images by P. Chris Christofferson

Since the bog is right by the side of the unpaved road, it’s easy to observe without wading in. Cypress rise up on their knees from the surface of water that’s not moving, but is certainly not stagnant – it’s rippling with life invisible to human eyes. The symphony of sounds generated from this small patch of swamp silenced our conversation. Nothing we could say to each other could be as fascinating as the calls and cries emerging from the marsh.

Our bird-photography score for the day may have been exceedingly low, yet we were finally rewarded with the sight of a prothonotary warbler. Although I recognized it from photographs, it was the first live one I’d ever seen. At once, I understand the thrill of bird-watching. Before this trip, I would have rated the excitement of the hobby as being slightly above the level of glacier racing. The yellow bird flited from limb to limb before us and refused to pose for our cameras, but that didn't dampen our joy. The things that did model for our cameras were the showy jungle-like flora of the area. Chris ended up snagging the Awesome Shot of the Day, capturing the image of a bee gathering nectar from a splendid white bloom. I couldn't identify either the plant nor the insect. It didn't seem to matter. Our morning ended when I was impaled in the thumb by a rusty fishhook while pushing myself up from a pond bank. Yet, even the possibility of tetanus had me dragging my heels, reluctant for our adventure to end. We added one item to carry in the car for future expeditions: a first aid kit. Leaving near noon, we were still besotted by the swamp experience. On the way home, we detoured and checked out the trail-head of the Possum Walk Heritage Trail in Logtown and the Ansley birding site, scouting them out for future expeditions – and for future editions of the Cleaver. Read the first article in this series about the Mississippi Coastal Birding Trail in Hancock County. Tips for beginning bird-watchers Swamp Spring

by Ana Balka

- "Here the people pull you in, and the swamp slowly plants your feet into its ever-shifting mud."

Bird pairs always remind me of older couples hunting for antiques. They poke around, mumble, and commiserate onwhich of our porch’s various corners and niches might suffice for their yearly egg condo. I don’t think these cardinals are going to take up residence in a garden clog today, but warblers might if we don’t turn them over. They were Northern Parulas, we figured out, the ones who came a couple of years ago and set up house in one of Steven’s boots.

I am neither a bird expert, nor do I possess a vast knowledge of trees, flowers, or other plants. I am, however, seeing the patterns of change come in waves, the cycles of the plants and animals with whom we share real estate becoming old friends as I see them repeat each year. I take photos of the massive camellia bushes coming into bloom, the Bradford pear as it goes white, the little turtles crossing the driveway, and the skinny young lizards, even though I realize that I have almost identical photo albums from last year and the year before. It makes me think of my grandmother, who lived in the Nebraska panhandle her whole life and wrote letters that summarized the arrival of the robins, the deer sightings, the spring rains, the calving, the growth of the flowers. In the Nebraska panhandle, the past is visible in the still-clear Oregon Trail ruts that cut through the grassy landscape on gentle plateaus. If you stand in the ruts on the small rise above the town where my grandparents grew up, the area below looks like a diorama, a set. It was incredible when I first saw the town from that angle, thinking of my grandparents living out there all those years with a relatively small cast of people and playing out life on this giant stage under the wide sky. In Hancock County, Mississippi, the past curls like jasmine in the trees, and rises and falls with the tides. When you take a kayak up Bayou Talla, or stand in Waveland at the corner of Nicholson Avenue and Beach Boulevard and look up at the lot where Eliza Nicholson’s mansion once stood, you can feel the past in ways unique to here. Many places like to say, “Once you’ve stayed here long enough, you won’t be able to leave,” but I can sense some truth to that in Hancock County. Here the people pull you in, and the swamp slowly plants your feet into its ever-shifting mud. continue reading below

My husband and I moved into a house on several acres of swamp and pasture next to Bayou Talla in February 2013. Neither of us had ever lived in this part of the country before, and neither of us had lived rurally in our adult lives. The last place we lived was London. He is Dutch; I’m originally from southeastern Nebraska, and we met in Atlanta. He’s a ship captain, so there was always a good chance that work would bring him to the Gulf. When we first met he would tease me about his romantic European desire to live in the swamps of Mississippi, and I would tell him that I sincerely wished him the best in that endeavor. I never suspected that less than five years later, I would be the one to locate a home for us in Kiln, Mississippi when his company wanted us to move to the Gulf Coast from London.

Say you live in the Kiln, and you will get some combination of a number of standard responses. If you’re anywhere between Baton Rouge and Mobile, whomever you’re talking to will tell you that their grandma/aunt/mother’s cousin is from the Kiln and they have amazing memories of going there as a kid and swimming in the river. Then they’ll ask if you know Brett Favre. They might ask if you have ever been to that, “...uuum, that one bar. What was it called... I saw it on ESPN. Oh—The Broke Spoke! You know that place?” People generally seem impressed when I say that yes, we live in the vicinity of the Broke Spoke, and I have indeed been there. At night, even. And yes, to the inevitable next question: I have had moonshine. Well wait, actually. I think it was homemade wine. The first year is always a fascinating time when you move into a community. Each person you meet has the potential to become a lifelong friend, and you have no idea what pattern you will weave into the local fabric over time. It felt like there was something more dramatic and poignant about that phase of living here than I’ve experienced in other places. Maybe it’s just me. Maybe it’s because so many of the people who live here actually grew up here, and come from families who have been here for generations. The history is right in front of you in the stories of the people you meet. Their very names tell stories. continue reading below

I attended a wedding last week in the Kiln, the marriage of the daughter of a friend we know through Pop’s Southern Comfort Foods on Highway 603. (Pop’s has been a focal point of our life in Kiln since Steven and I arrived, which is something you can read more about here. We love Pop’s. You should go there.) More than 500 people crowded into the Church of the Annunciation (which used to be the gymnasium of Kiln Consolidated High School until the school closed in 1959; the smaller, original church is just across the road), for the wedding.

Probably a third of Kiln’s population was packed into that church and/or at the reception afterwards (it was a spectacular wedding—congratulations to Lindsey (Lee) and Jonathan Bounds). Here was the continuing narrative of a place that has seen breathtaking ups and catastrophic downs—followed by renewal—that is in many ways typical of small town America, but whose stories are anything but typical. I would not have missed being there, even though I did not know tons of people at the wedding. This was part of the history of the people of this town. Kiln’s first European settlers came in the early 18th century to an area originally inhabited by Choctaw and Muskhogean people (see the Hancock County Historical Society’s fantastic website for this and so much more). Many more people arrived during the booming timber milling years, and Kiln was a thriving town with good services and schools. But after 1930, following the forests’ depletion and the resulting mill closings (not to mention the stock market crash and the Depression that followed), people either left or stayed and did what they could to get by. For some, that apparently included capitalizing on location, resources, and know-how to create a moonshine economy during the mid-century. This left Kiln with more of an outlawish reputation than may be deserved. continue reading below

Then of course, everyone in this part of the country knows about the cycles of loss and rebirth when it comes to the weather: Everyone here has a story, and many people have told me that Katrina took everything they had. Tell someone in Kiln, Waveland, or Bay St. Louis that you think this is an amazing place, and there is a good chance they’ll say, “You should have seen it before.” I tell outsiders that now I understand much more about what was lost, and what can’t be taken away from this place and these people, and what compels a community to rebuild and ride out more seasons.

The warblers are back. They’re checking out a flowerpot in the collection of toys that we’ve accrued from our walks on the beach. Maybe they’ll set up their little incubator in there this year. Sprouting Up by Melinda Boudreaux - this month - Take a look around town, because this spring it's going to be greener than ever!

I’m talking about the planting of grand Willow Oaks, blooming Crape Myrtles, bright Vitex. Well, they aren’t big, blooming, and colorful yet. These 45 deciduous trees are just freshly planted, thanks to Katharine Ohman, Dan Batson, the Beautification Division, and airmen from Keesler Air Force Base. Since Hurricane Katrina, there have been numerous other beautification projects in the city, all with the help of volunteers and donations. The goal of the Beautification Division and Katharine Ohman is to “re-green” our area and in doing so, add to “its intrinsic value,” Katharine tells me. Ideally, in the long run, that intrinsic value aids tourism and economic development. Overall, these cosmetic improvements have been positive for residents and business owners. Local antique and art dealer, Althea Boudreaux, is grateful to have two new Crape Myrtles in front of her business Something Special on 207 Main. “Without a doubt, the addition of the Crape Myrtle trees creates an ambiance of Southern charm and warmth to the 100-year-old cottages of the 200 block,” she says. Katharine has been a part of many steps in the process of re-greening our city and county. She, along with the Beautification Division and Chamber of Commerce, put great care into projects like this one. Katharine has personally been involved with maintaining funding by donations, planning and organization, volunteer management, and compiling reports . “I also get my hands and boots dirty on most projects,” she adds. story continued below  Part of ensuring proper use of the donations is choosing the right vegetation to re-green our area. Katharine assures they “try to obtain native species or those that are well-suited to the area soils and climate.” Crepe Myrtles, Oaks, Magnolias, and Vitex thrive in our area. Because these trees are expected to be large monuments on our landscape, the BSL Beautification Division also takes proper and legal precautions around roads, taking into account power lines, underground pipes, and driver sight lines. How is Bay St. Louis able to obtain so many beautiful trees? Katharine explains, “Donations come from several sources, however chief among them is Dan Batson’s GreenForest Nursery in Perkinston, Mississippi.” Dan is a generous contributor to our area, since 2006. He offered donations of trees and vegetation to many Gulf Coast communities after Katrina destroyed so much of the greenery. “Bay St. Louis was almost the only one to respond, and Dan was confident that the products of his generosity would not be wasted,” Katharine says. Small efforts like this one are certainly not wasted on Bay St. Louis. The addition of new greenery helps to replace the estimated 320 million trees along the Gulf Coast lost to Katrina, according to a study by Jeff Chambers, a Tulane University biology professor. Thanks to the BSL Beautification Division, Katharine Ohman, Dan Batson, and the armies of volunteers from Keesler, Americorps, Habitat for Humanity, Master Gardners, the local NAACP, and so many more, our local ecosystem can breath a lot easier. The Infinite Difference by Sue Louvier - A connection with a bluebird gives a "glimpse of grace that few people experience in a lifetime."