Community consensus can help Bay St. Louis set our course for the future, so bring on a new Comprehensive Plan.

- by Ellis Anderson

As the holidays draw near and infection rates break new records, the possibility of gifting the virus is a prospect we can avoid.

- by Ellis Anderson

The Mississippi Department of Health/University of MS Medical Center now offer free statewide drive-thru Covid testing. You do not need a doctor's referral. To qualify, you need to have some Covid symptoms or been exposed.

It's extremely simple to make an appointment through their online system! Click here. Want to see a snapshot of how your Mississippi county has fared with infection rates over time? Click here.

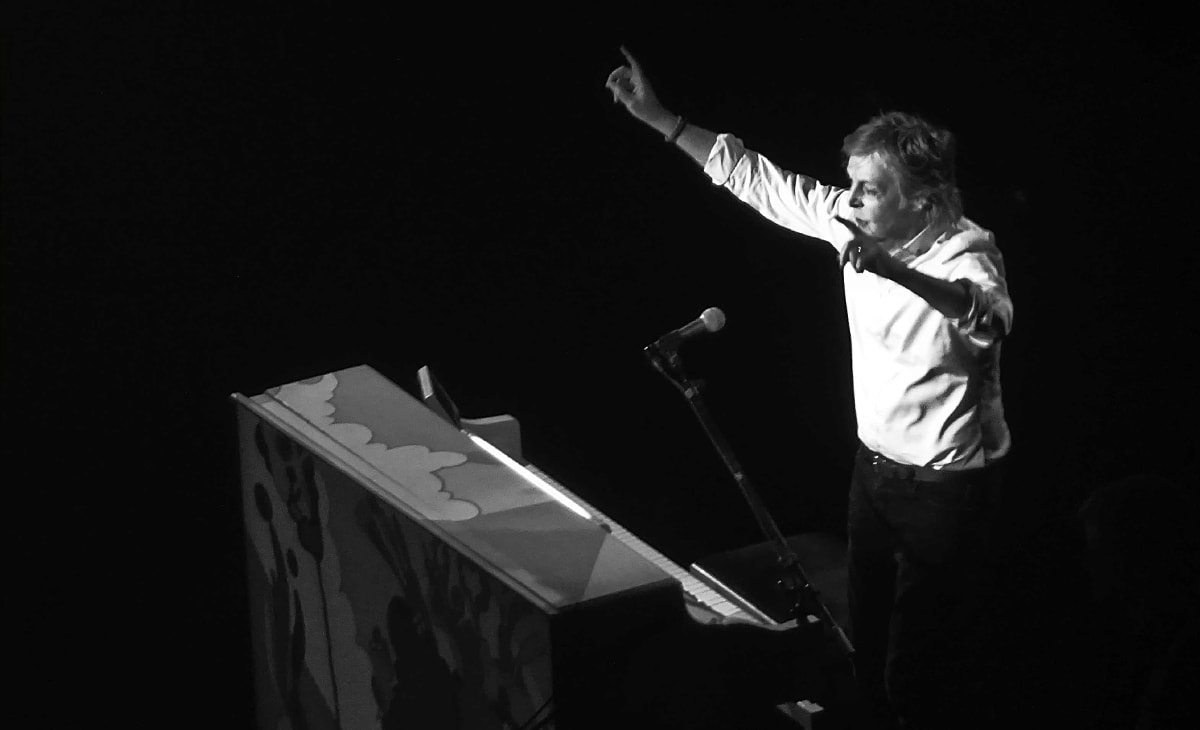

After fifty years of adoration, a Paul McCartney fan shares an intimate moment with him - along with 18,000 other fans.

- story by Ellis Anderson

A roving robot named after an English butler becomes a beloved new pet, despite the skepticism of the family dogs.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

Shoofly Magazine publisher Ellis Anderson looks back to the first Cruisin' the Coast event in 1996 - and her introduction to the Pat Murphy Band.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

These three fun itineraries for idyllic days in "The Bay" are tailored for fitness buffs, families with children and BFFs who want to explore Old Town's shops. You won't go hungry either, with our local eatery suggestions. Feel free to mix and match at will - you really can't go wrong.

- itineraries and photos by Ellis Anderson

In the century since it'd been constructed, the building had served as a school, a community center and a place for healing broken lives. But no one had ever called it "home."

- by Ellis Anderson

Coast Lines - Oct/Nov 2017

One man helped shaped the creative heart of Bay St. Louis in ways that will happily reverberate for generations to come: meet Jerry Dixon.

- story by Ellis Anderson Free Willy Gone Wrong

An impulse to save a crafty crab ends well for the creature, but its rescuer has reason to wish she'd eaten it instead.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson A Newcomer's Reconciliation

Learning to see the invisible net of community - woven from both past and place - enriches the life of one suburban transplant.

- by Ellis Anderson Paying Your Respects

Could an outpouring of community condolences on the loss of an antisocial dog stem from the coast's hurricane culture?

- story and photo by Ellis Anderson God's Perfect Creatures

The Gulf Coast's on-going battle with Formosan termites will have us swatting the swarmers this May as the over-achieving insects scout out more trees, homes - and boats - to devour.

- story by Ellis Anderson Mardi Gras Miracles

The New Orleans celebration seen on TV around the country differs from the local experience, where miracles - both small and large - are commonplace.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson Compare Answers, Not Ads

A new non-partisan website gives local candidates a place to introduce themselves and share detailed answers to important questions. Elections in Bay St. Louis may never be the same.

- by Ellis Anderson Kind to Insects

Of course, bugs can't think or communicate with humans - or can they?

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson Open Windows

After a seemingly endless summer, the first cool evening of the fall has coast residents turning off the A/C and reveling in fresh air.

- story and photo by Ellis Anderson

Animated Vs. Animals

The Pokémon GO craze may have more people walking around outdoors, but they're oblivious to local flora and fauna, in pursuit of tiny cartoons.

- story by Ellis Anderson

The Company of Trees

It turns out the trees are social beings that have feelings and can communicate. Some folks aren't surprised.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

A Shoofly Way of Life

A change of name kicks off an International Shoofly Awareness campaign, in hopes of reviving a fine and neighborly tradition, while creating a new Mississippi export.

- story by Ellis Anderson, artwork by Zita Waller

Bye Ward, Hello Shoofly!

Ward and June are going into retirement, as the Fourth Ward Cleaver web-zine changes its name to "The Shoofly" in July! Read on for why.

- story by Ellis Anderson |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed