This year’s Juneteenth celebration marked the twenty-third consecutive year that Waveland Helping Hands has sponsored the event.

- by Maurice Singleton

She lived through segregation, she knew discrimination – and fought back as an activist. But Clementine Williams is best known and loved as a dedicated educator.

- by Maurice Singleton

Adults in Bay St. Louis conspired to keep secret the identity of the Santa who wore shrimp boots and arrived by seaplane each year.

- story by Ellis Anderson, photos courtesy Pat Murphy, Prima Luke and Melva Luke

Venerated New Orleans musician Deacon John is beloved as much - if not more - on the Mississippi Coast.

- by Pat Murphy

Engraved bronze plaques are enhancing worn markers at the small cemetery on Hancock Street, the final resting place for the Brothers of the Sacred Heart.

- by Lisa Monti

The Hancock County Historical Society is premiering a new documentary in December showcasing area history and the man who makes it come alive, Charles Gray.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

In this popular story from our Shoofly archives, learn how internationally revered piano genius James Booker spent time growing up in Bay St. Louis. Writer Edward Gibson traces some of those early years and explains why the Bay was always a touchstone for the legend, who died too young.

Booker Fest 2021 takes place in Bay St. Louis on December 3 - 5. Scroll down to end of essay for the full schedule or click here for tickets.

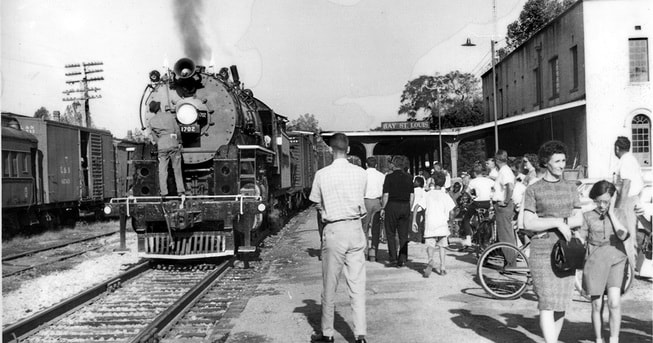

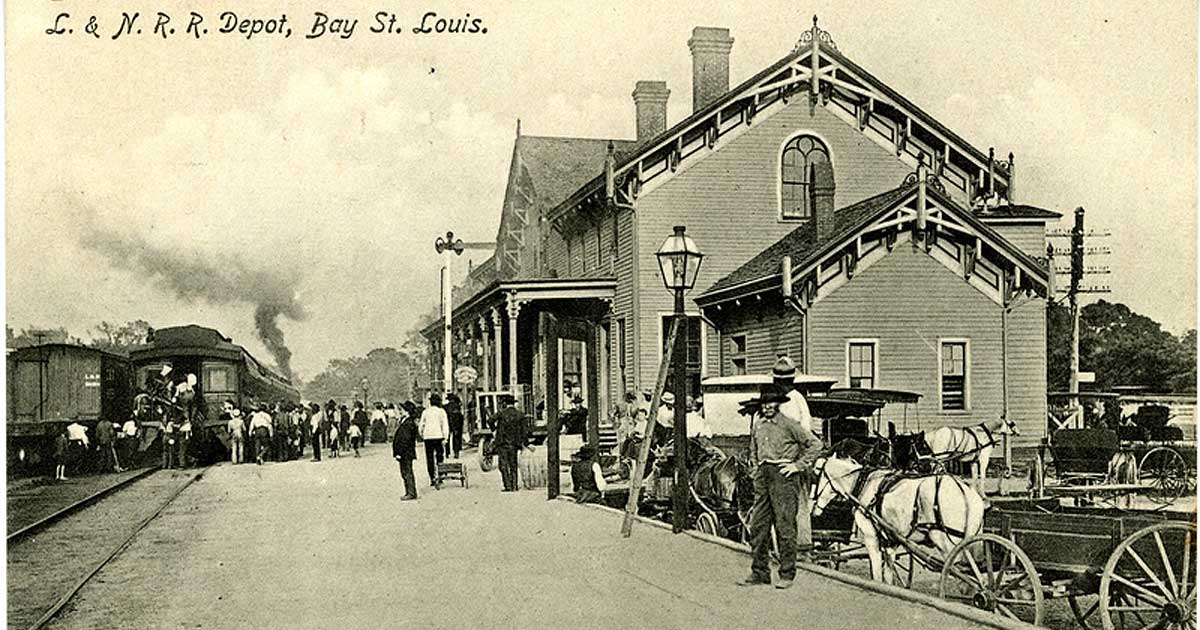

What will it take to make a train experience so special, so inviting, that people from New Orleans and Mobile will choose to step onto our Depot platform for an unforgettable Bay Saint Louis vacation? The answer might just be found in our history – and our future decisions.

- by J. Michael Dumoulin

Miss the previous two stories in this series? Never fear!

The event’s been celebrated in Hancock County for more than a decade, but this year, it’s a federally recognized holiday.

- by Wendy Sullivan

In Part One we looked at the history of rail service in Bay St. Louis, and at the depot building. This month we turn our attention to the history of the depot district itself.

- by J. Michael Dumoulin

If you're excited about the possibility of restored passenger rail service in Bay St. Louis, find out how it all began.

- by J. Michael Dumoulin

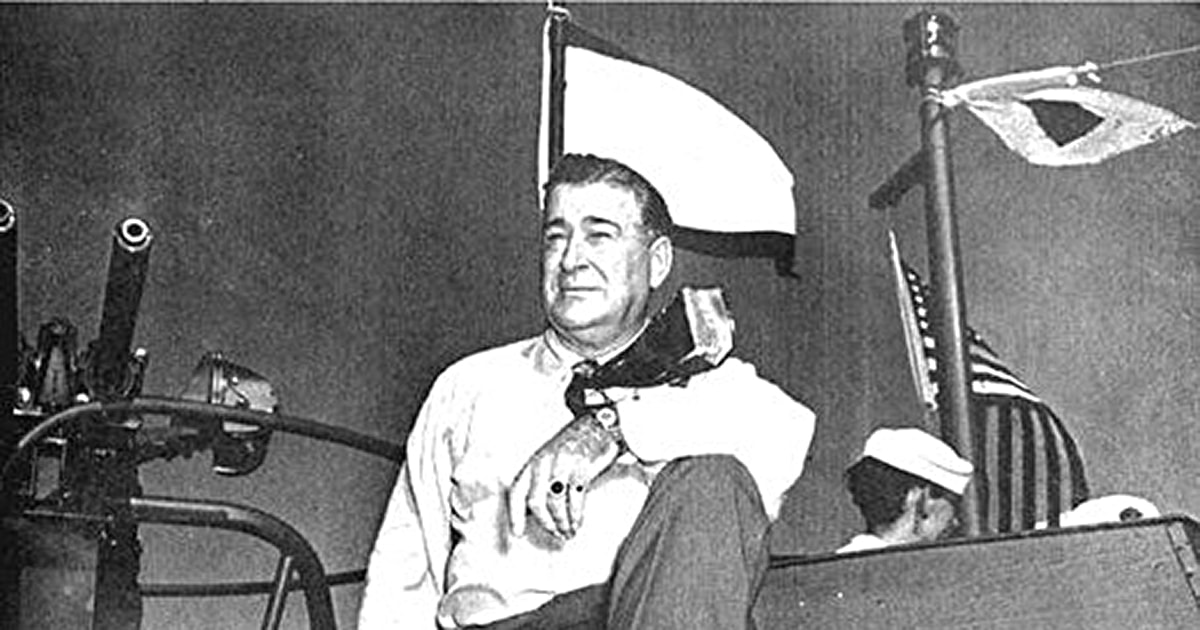

The family of Andrew Higgins, the boat designer who has been credited for winning WWII, have long time ties to Bay St. Louis.

- Story by Dena Temple

The current COVID-19 crisis isn’t the first time Bay-Waveland has faced an epidemic. Read about the 1897 Yellow Fever epidemic and how the community staged an organized fight.

- Story by Jerry Beaugez

In honor of Black History Month, the author looks back at three BSL residents whose character and service helped shape our community.

- Story by Jerry Beaugez

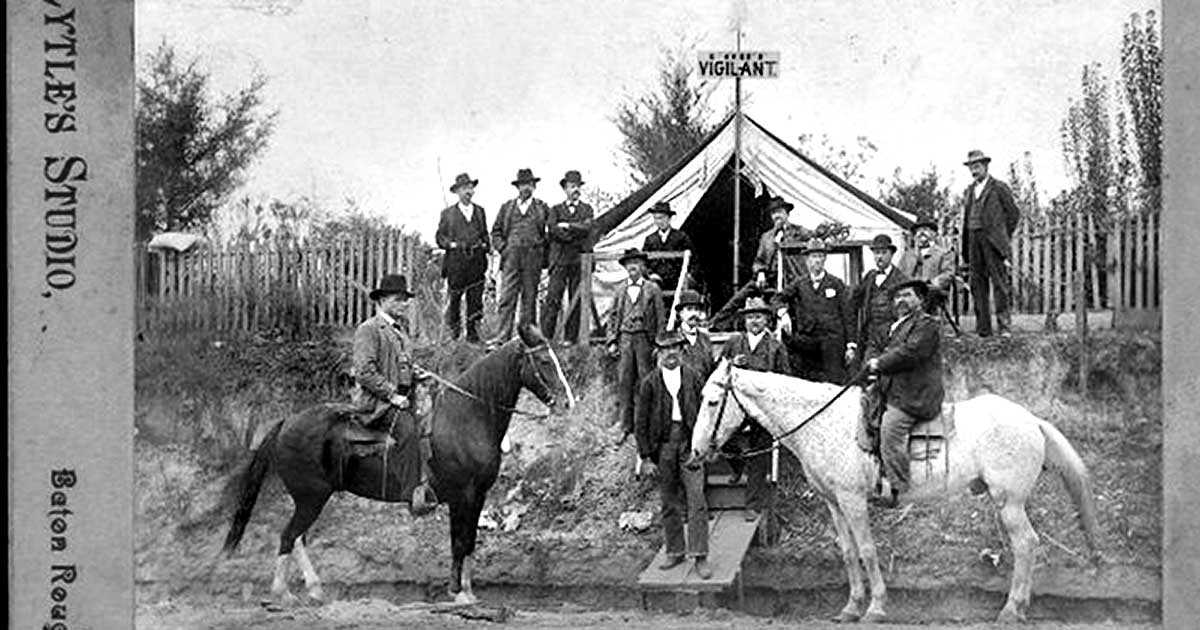

Every community is the sum of its residents, past and present. But we'll bet that none of these gentlemen had an inkling that we would be talking about them more than a century after they left us.

- Story by Jerry Beaugez

No man was more accommodating or had more friends than he. If anyone met him and said they were hungry, Polite would say, “Well, you can’t eat your hat. Here, try this,” and he would leave them with something to eat. The mailman, messenger, general delivery man and baker all in one great character continued to helping others for nearly half a century. Mr. Polite passed away in 1930. Rufus Randolph Perkins

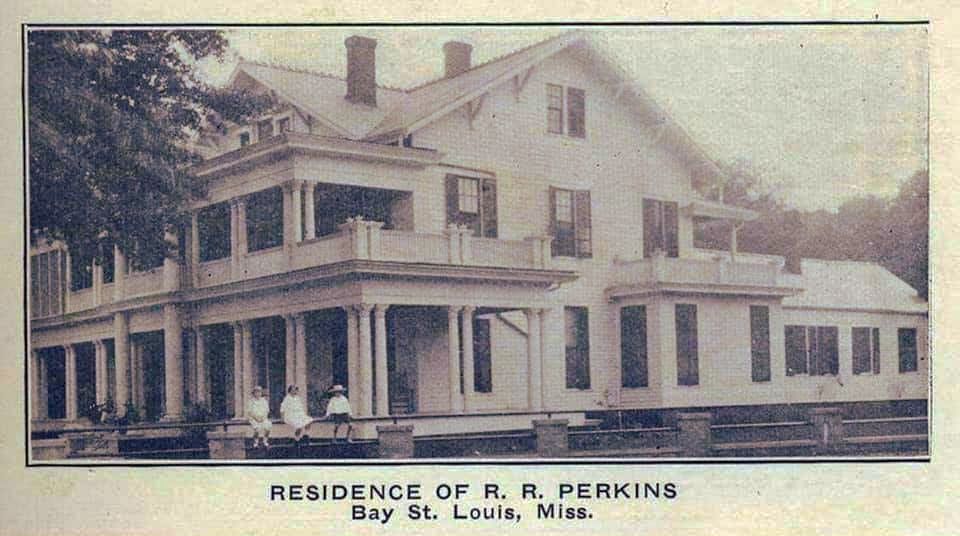

R.R. Perkins was known as a “big operator” in Bay St. Louis. Born in Bernice, South Carolina, in 1869, he and his family moved to Broxton, Georgia, where he met and married Tempie Lott. Perkins moved to Bay St. Louis in 1903 where he and his wife raised six children.

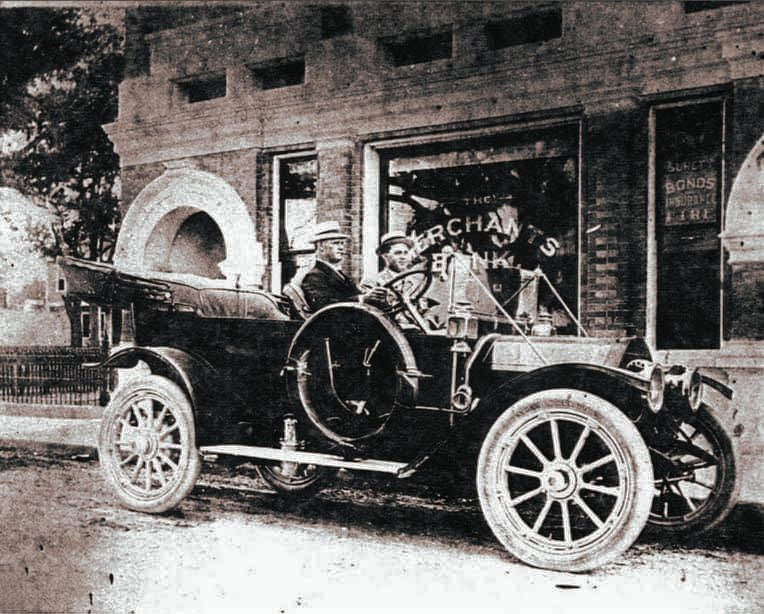

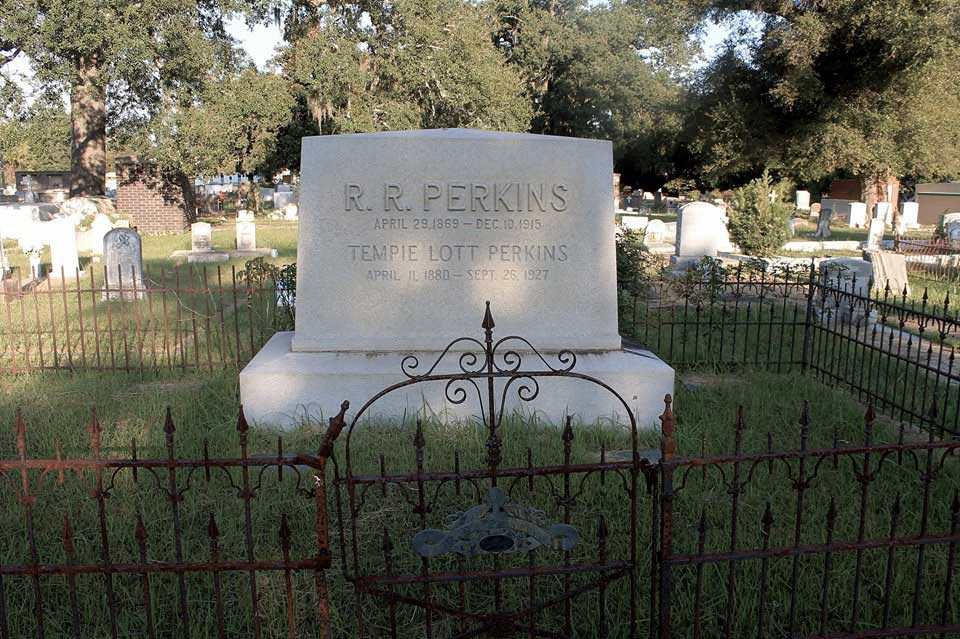

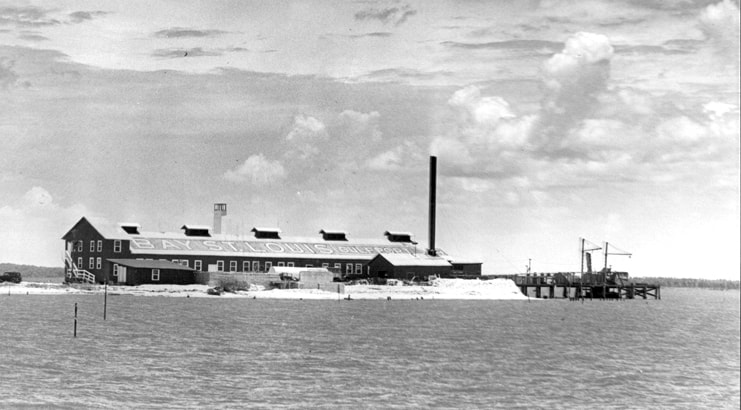

Mr. Perkins was the president of the Imperial Naval Stores Company and the Hancock Naval Stores Company, one of the largest companies of its type in Mississippi at the time, which produced such items as resin, tar, and timber used for sailing ships. The company also produced pine oil, pitch, and turpentine which were shipped through New Orleans, Mobile, and Gulfport. Under Perkins’s supervision from its Bay St. Louis headquarters, the Hancock Naval Stores Company was capitalized at half a million dollars. Today that would earn him $12,500,000.00. Perkins was also the president of the Merchant’s Bank, which was originally housed on Beach Boulevard just south of the tracks. The building remained standing until 2005 when Hurricane Katrina heavily damaged the structure, and it was eventually torn down. Perkins was a kind and giving man who quietly dispensed with an open heart to many charities as well as family and friends alike. When he passed away on December 10, 1915, his obituary stated, “He had the biggest trust in mankind; ever hopeful, his life was indeed an inspiration to those who knew him.” His tombstone is as large as his presence in the history of Bay St. Louis and is the largest single stone in the Cedar Rest Cemetery, weighing 1,700 pounds. The stone was brought from New Orleans by train, which stopped at Second Street; there it was loaded onto a skid and was pulled by eight mules to mark his final resting place. Ludovic A. de Montluzin

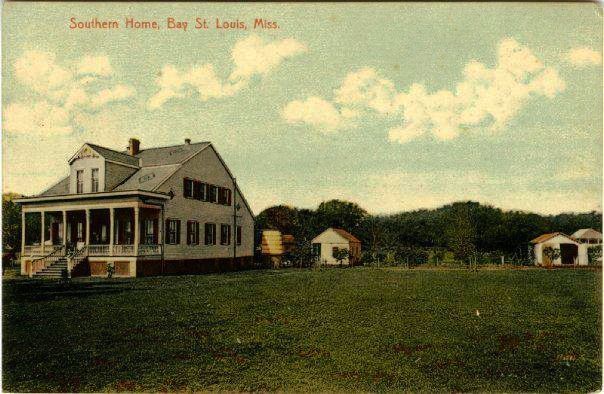

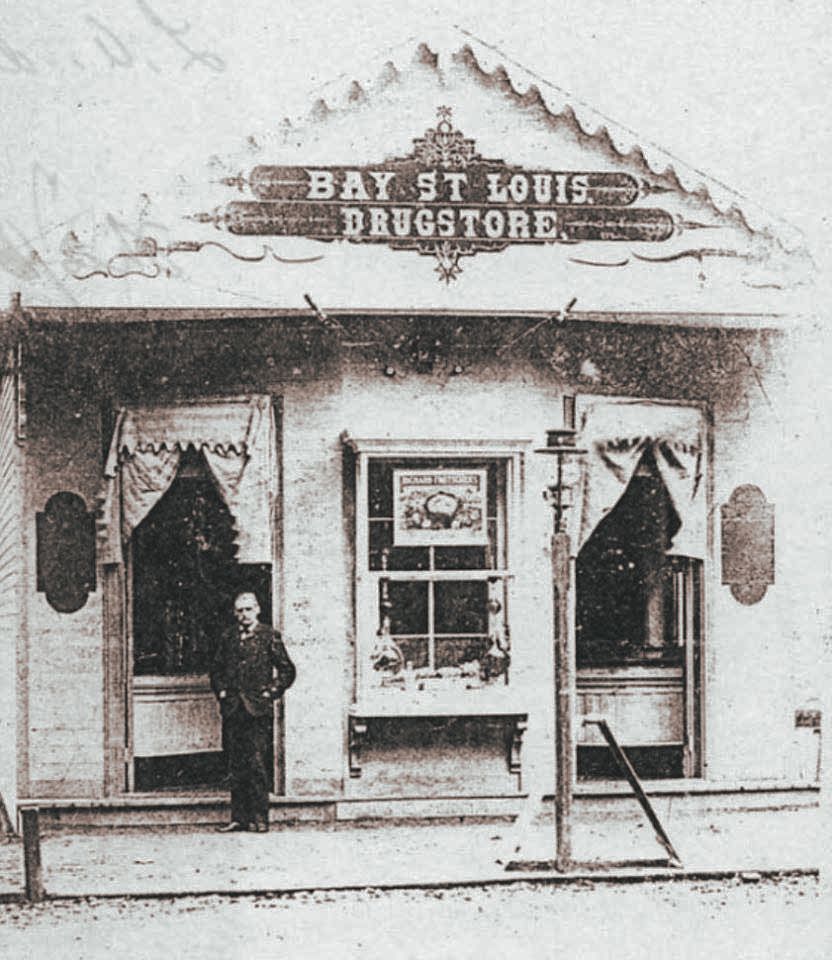

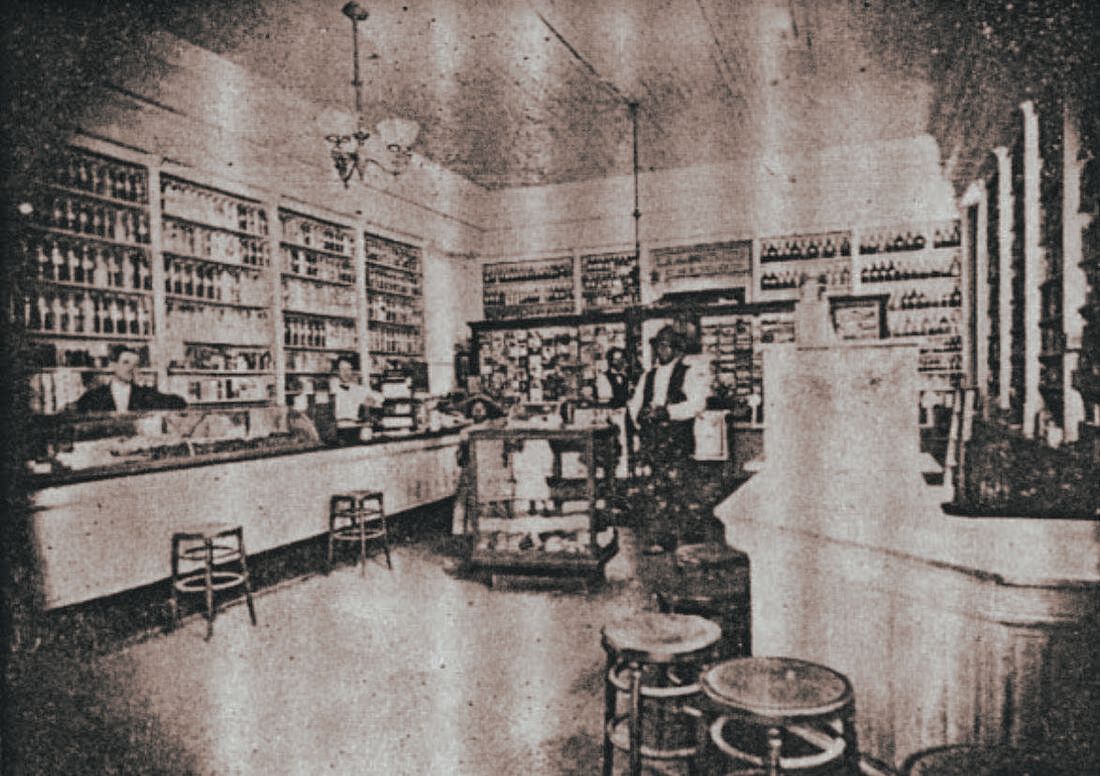

For nearly 100 years the de Montluzin name was known in Bay St. Louis as a distinguished family and the proprietors of the city’s oldest and most reputable pharmacy. Ludovic A. de Montluzin, otherwise known as “L.A.” was born in December of 1827 in the town of Luneville in the province of Lorraine, France. An idealistic young journalist with political opposition to the French Emperor Napoleon III, de Montluzin felt despair for the future of France and emigrated to the United States with his wife, Reine Helluy de Montluzin, and their three small children. Settling in Louisiana, the couple had three more children. In 1878, L.A. suffered a heart attack and, at the urging of his doctors, he retired to Bay St. Louis to “give up some of his activities.”

L.A., Reine and their six children began their new lives in Bay St. Louis. Their family home was located at 208 North Beach Boulevard, at the foot of what is now de Montluzin Avenue. The de Montluzin home would later become the original Bay Town Inn, which was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. While looking for a hobby to pass his time, L.A. decided to open a pharmacy. The de Montluzin Drug Store was opened on Beach Boulevard in 1878 and soon became a trusted establishment for stocking pure, fresh drugs, sundries, toiletries and other quality goods. L.A. and Reine’s son, Rene, received his pharmacist license in 1893 and worked alongside his father. The devotion to his wife and family was very strong. During a deadly yellow fever epidemic along the Gulf Coast, Mrs. de Montluzin took her two youngest children to visit her family in Paris. Her husband missed her greatly, and letters to her during this time “overflowed with his tenderness and love.” That love of the two remained constant for 62 years until the death of L.A. on December 26, 1909. Heartbroken and not desiring to live, Reine took to her bed, and on January 19, 1910, she passed away, simply by willing it so. A love like that can only be described by the Latin inscription engraved inside her husband’s wedding ring, Virtus iunxit; mors non separabit – “Virtue united us; death will not separate us.” Their son, Rene, continued to operate the de Montluzin and Sons Drug Store for years. Rene passed away on February 18, 1959, at the age of 93. His son, Rene Jr., would become the third generation to carry on the family business, doing so until his death in 1977. The pharmacy was then closed, and patient records were transferred to another pharmacy in town. The oldest and most trusted name in pharmacies in Bay St. Louis was in continuous operation just short of 100 years. Many older residents of Bay St. Louis still speak of the de Montluzin family and the de Montluzin & Sons Drug Store.

The list of needed repairs was long - but the dedication of the designers, carpenters, craftsmen and artists returned this house of God to its former glory.

- Story by Lisa Monti, photos by Nina Cork and Drew Tartar

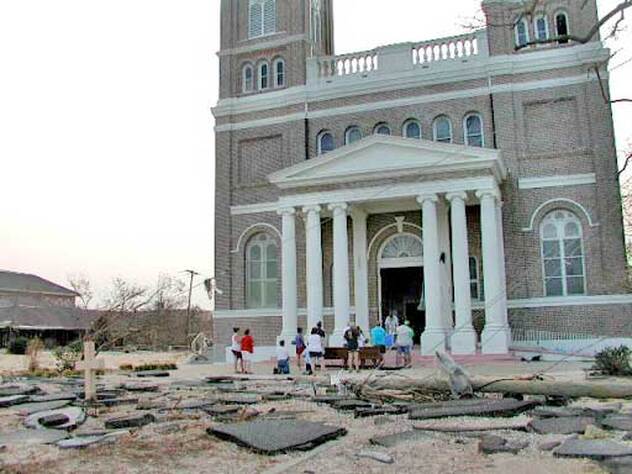

The parish footprint has been in the same beachfront spot for almost 175 years. The current brick church was completed in 1908 after a devastating fire the year before that also destroyed St. Joseph Academy and other buildings on the beach road. It withstood many storms over the years and rebounded from the damage. When Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, the church’s roof was torn off, the interior flooded and the marble altar rail was broken into pieces.

Major repairs were made after the storm, including a new roof, but problems persisted. “We had leaks in the roof for the last 12 years, and termite damage,” said Joe Monti, a lifelong parishioner. After those issues were finally resolved, the parish was able to move ahead with plans to restore the church interior with new paint and lighting and other needed improvements. The project was a year in the making, said Wikoff, who selected the new color scheme for the church. In January, church services were moved to the adjacent Community Center as paint contractors set up scaffolding to prep and paint the ceiling, walls and columns. Parishioner Rick Martin directed the scaffolding placement, wall restoration and the painting contractors. There was so much scaffolding, the work being done wasn’t visible from below. “It was like the Sistine Chapel,” Monti said. “You didn’t know what it looked like until the scaffolding was gone.” Parishioner Nina Cork, an artist, used her talents and background in iconography to restore the canvas murals depicting Mary as Our Lady of the Gulf attached to the dome and the ceiling panels of saints. That required her to work 50 feet up in the air and without the benefit of seeing her progress from the vantage point of a pew. She also added the gold leaf throughout the sanctuary and on top of the columns. “I spent my entire 10 weeks on scaffolding,” she said. “I’d never done that before.”

Cork repainted the top third of the image of Mary to keep it as close to the original image as possible and to keep the church’s namesake as the focal point above the main altar. It’s not known who originally painted the church’s murals. To brighten up the church’s interior, LED lights were installed to illuminate the space and highlight the stained glass windows, the Stations of the Cross and to put the focus on the altar. The LED lights on the side aisles now match those in the large center aisle and new lighting has been added to the various niches around the church. The church’s stained glass windows, some of which were crafted in Germany decades ago, were outlined in dark blue paint and cleaned up so the colors and features were enhanced. The Stations of the Cross along both sides of the walls date back to the 1920s and were taken down for the church renovation. Parishioner Joann Hille hand painted the plaster, three dimensional Stations some months ago and did some retouching where it was needed after the stations were hung back on the church walls. Parishioners got to see their renovated church on Easter weekend, after volunteers cleaned and dusted, all the Carrara marble statues were uncovered and the artwork was back in place. “It was a long process but it came together at the last minute,” Monti said.

Cork called the renovation “a wonderful team effort, with everybody using his or her skills. We all had our own vision but to see it all pulled together, it’s just amazing.” There’s still some work to be done, most notably the return of the original altar rail severely damaged by Katrina and a redesign of cabinets in the sacristy behind the altar.

Father Mike said that OLG has always been recognized as a beautiful church and that made the prospect of changing some interior features a bit daunting. “Due to the research, hard-work and talent of so many, I believe we have really made almost everyone happy. I feel truly blessed by the results of the renovations, and I am happy for the parishioners of OLG and the many visitors we host here,” he said. “Going all the way back the Temple of Solomon, we recognize that the beauty of ‘God’s house’ should raise the mind and heart to contemplate the beauty of God’s truth and presence. I believe OLG does that as good as ever. I could not be more grateful for the team of professionals and volunteers that made this renovation a success.”

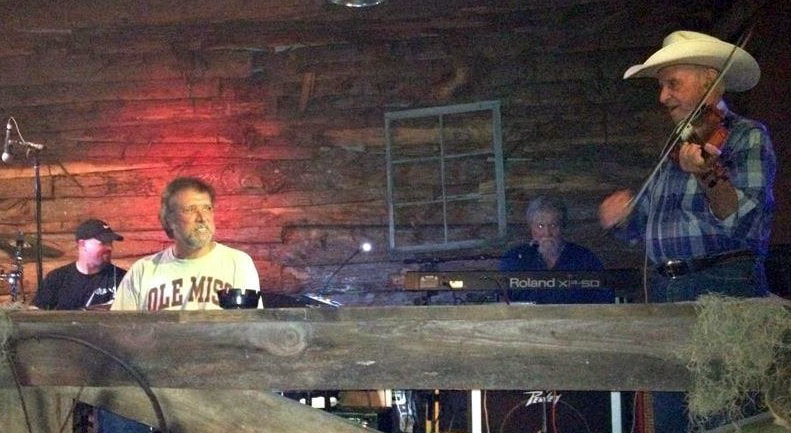

This local musician's talents are woven into the fabric of our American musical heritage.

- story by Edward Gibson, photos courtesy the Moran family

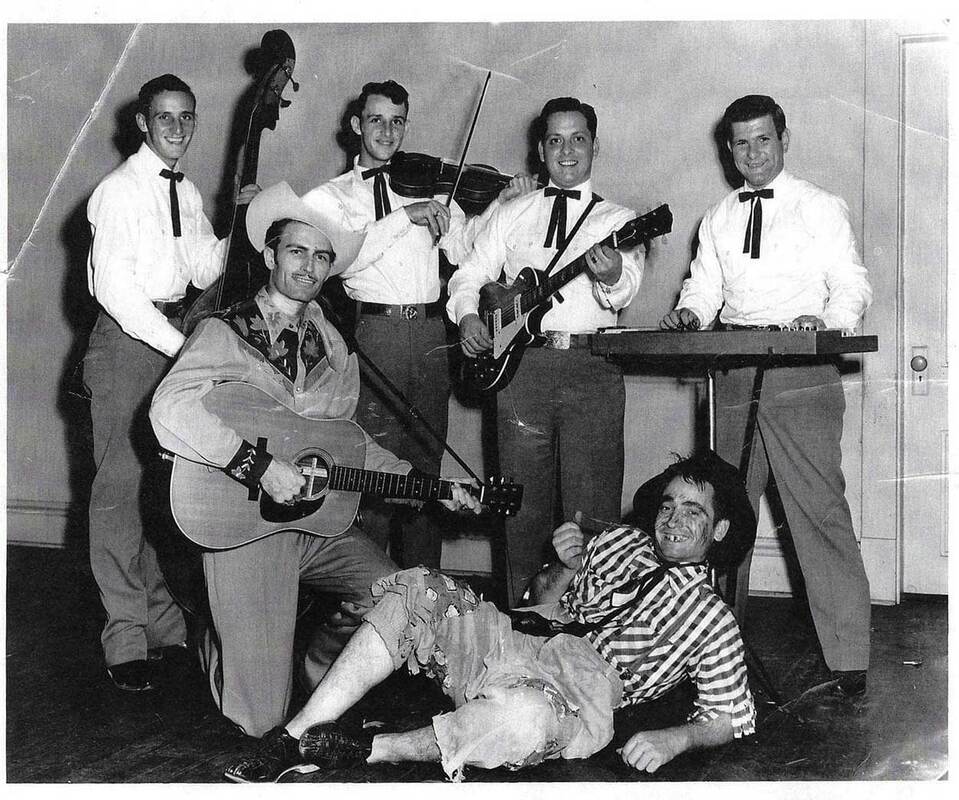

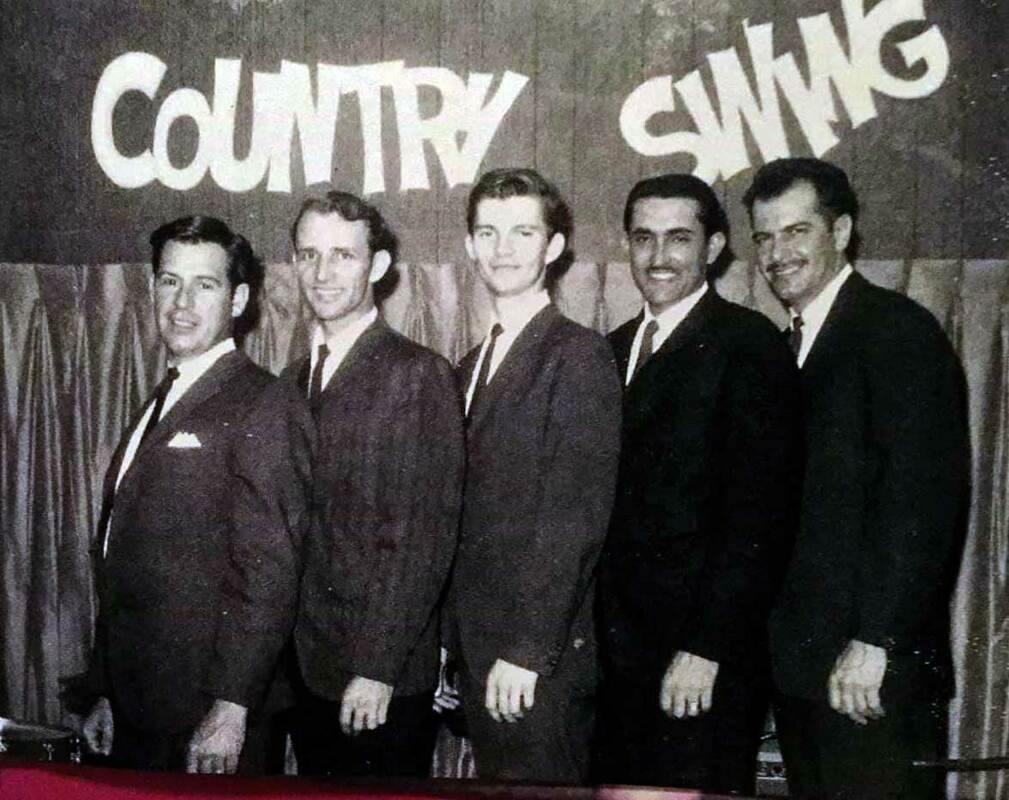

At twenty years old, he joined a band led by Werly Fairburn. Fairburn, the “singing barber,” is a lost legend of rockabilly, one of the few that successfully transitioned from country to the “new” music. This was in 1953, before Werly turned away from country.

“Werly was a good songwriter and a good singer. He was serious about it,” said Tommy. Tommy moved to New Orleans, and along with his brother, Ola Gene, backed Fairburn. They recorded Werly’s music and played live fifteen minutes every day on WDSU. The group earned extra money playing dances and barrooms. Soon, Fairburn and Moran landed a gig on the Louisiana Hayride. There, they shared the bill with Johnny Horton and Elvis Presley. From there, they went to the Grand Ole Opry, playing alongside the royalty of country music, most notably, the great Webb Pierce. But music is always changing, and country was giving way to rock 'n' roll. Tommy played a bill at Pontchartrain Beach with Presley. Tommy said, “They wanted to tear his clothes off of him. That always baffled me.” By the late fifties the Bakersfield sound was catching on, and Fairburn wanted to move to move west and cash in. “I wouldn’t go,” Tommy said. “I figured I had never lost anything in Bakersfield, and so I didn’t have to go out there to find it.” Besides, it was the old-timey music Tommy loved, “Fire on the Mountain” and “Billy in the Low Ground.” For the next ten years, Tommy also became a popular session musician. He recorded in Nashville and at the Studio in the Woods in Bogalusa. Along with the many unknowns, he recorded with Loretta Lynn and Don Price. He played with Dolly Parton and George “Possum” Jones. But the recording artist has enjoyed performing as well. Early on, Tommy formed the Moran Family band with two brothers and two sisters (listen to one of their recordings at the end of this story). Along with his talented son, "Little" Tommy Moran, he toured with Moe Bandy. And he took home numerous top prizes from fiddling competitions through the years. But mostly, he cut timber. He worked oxen long after the mechanization of the timber business. Tommy said he cut less timber, but he could make more without the cost of skidders and tractors. He could feed an ox for a dollar a day. They never broke down, and I think he liked the quiet of the woods and the company of the animals. We talked about the players he liked, consummate session and side men like Don Rich, Roy Clark, Jerry Reed and Glen Campbell. A good player, he said, isn’t out front. He is there in a way that you hardly notice, but if he wasn’t there, the song would be missing something. Two of his sons, Tommy and Gene, are carrying on the family tradition, currently playing together in "Monsters at Large" (catch them at 100 Men Hall, June 21, 2019). Years ago, I had an opportunity to play at church with Tommy Moran and his wife Annette. He came out day or two before. We ran through the number I picked, Doc Watson’s “I am a Pilgrim.” I asked him if he wanted to run through it again. "That’s all right,” Tommy said, “I got it.” Yes, he did. In the recording below, Tommy Moran's brother, Doug Moran (now deceased) sings lead.Tommy Moran plays in this 2012 video by BSL singer-songwriter Rochelle Harper

Special thanks to Tommy Moran's daughter Michele Seal for photo/video assist for this story!

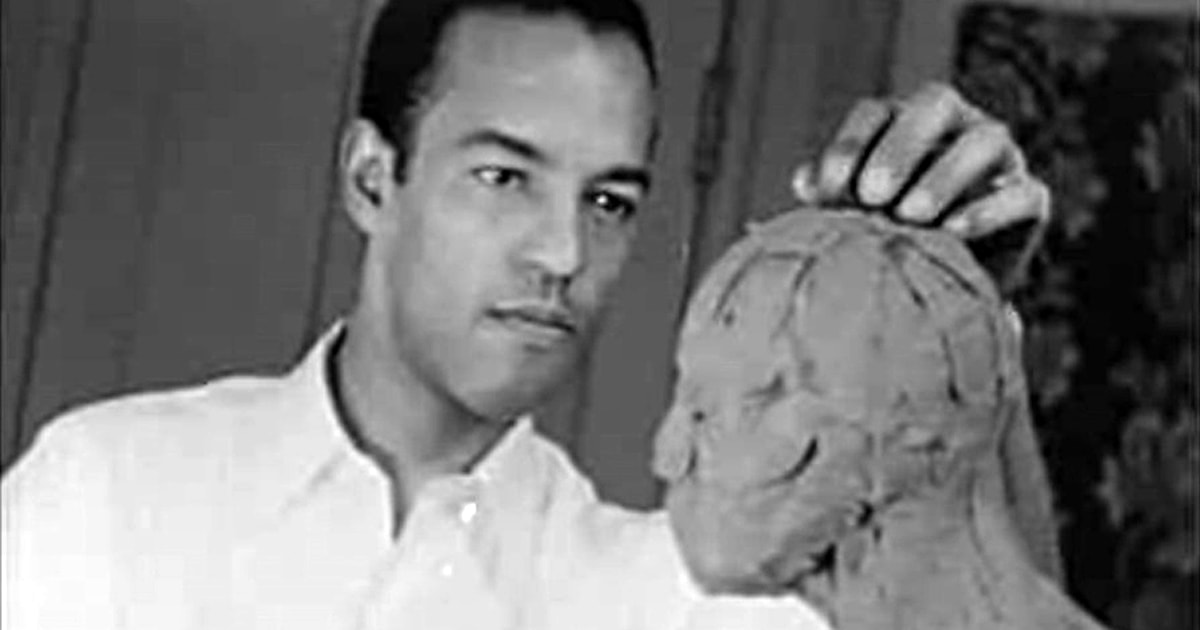

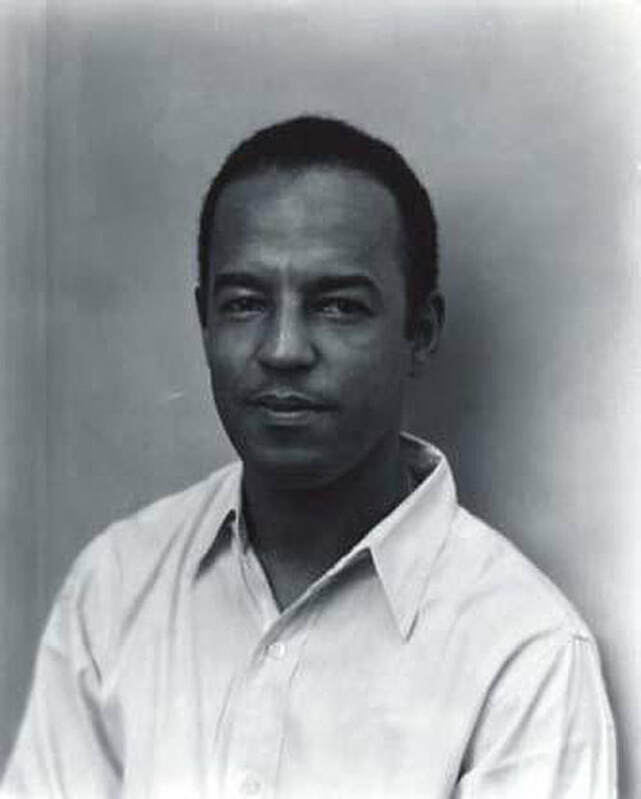

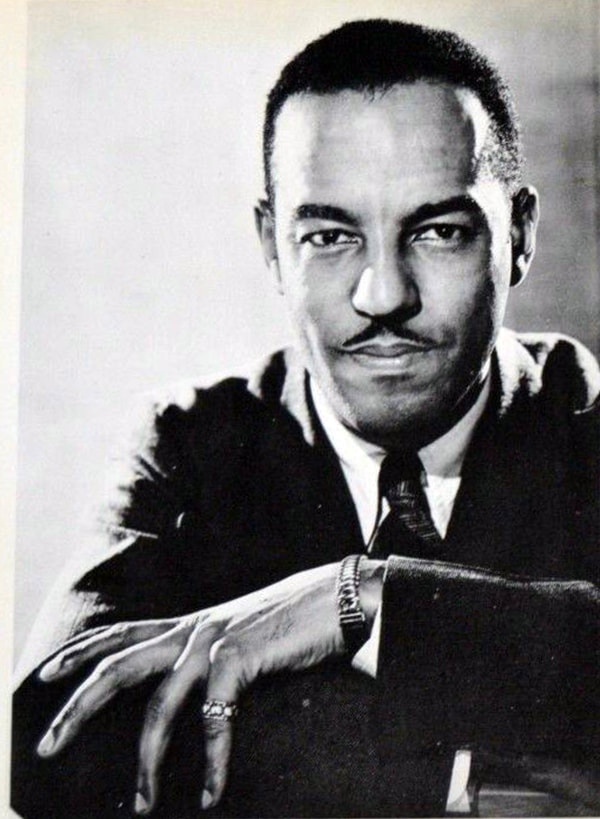

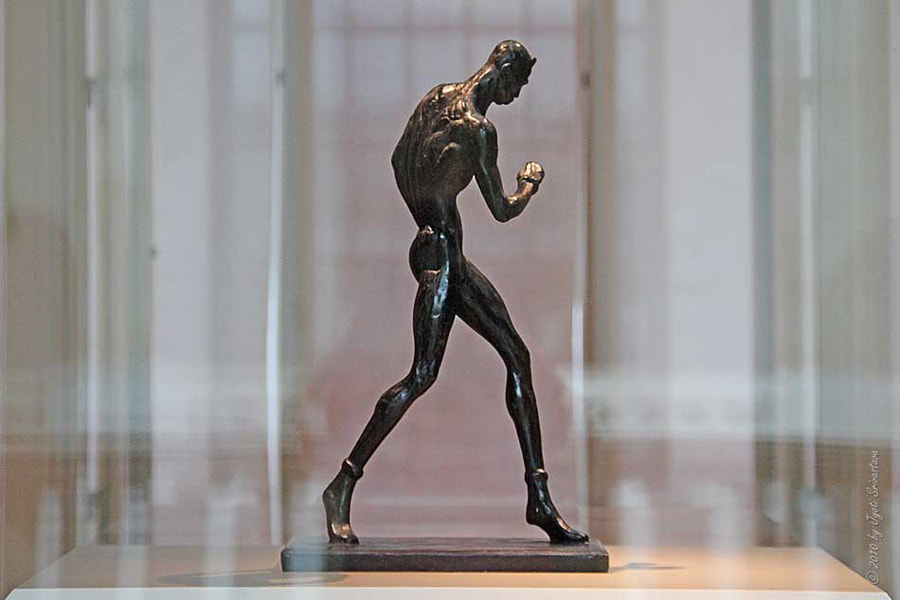

Richmond Barthé left Bay St. Louis at age fourteen. He became one of 20th century America’s greatest sculptors of the human form - and Mississippi’s preeminent artist in the field.

- story by Edward Gibson

According to Celestine Labat, in the oral history preserved by Lori Gordon, Barthé was pronounced like “hearth.” His mother, the Creole Clemente’ Rabateau, hailed from a family of craftsmen, and his father, Richmond Barthé, an “American” as the Creoles disparaged, was a dark-skinned, grey-eyed African-American. The elder Richmond died within months of Jimmy’s birth.

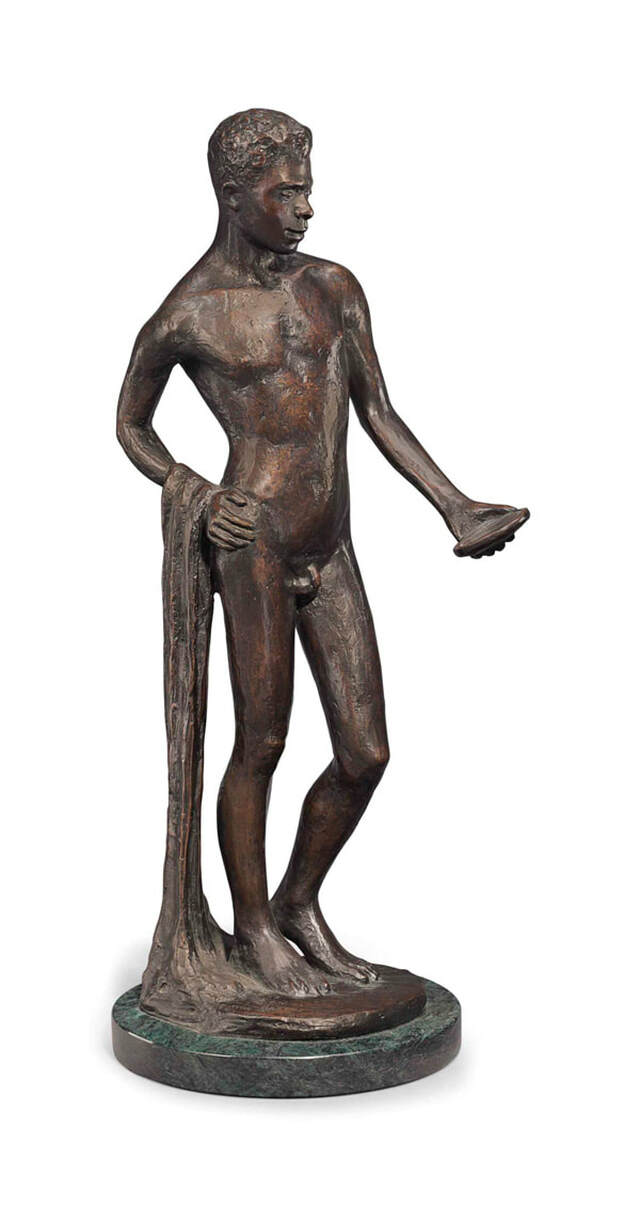

Jimmy enrolled at the newly formed St. Rose school where he met Celestine Labat’s sister, Inez Labat. The teacher Labat recognized Jimmy’s talent for drawing and encouraged him with both praise and a supply of pencils and paper. Inez Labat encouraged the young artist throughout his life. Jimmy’s talent for portraiture soon drew the attention of the town, and the Pond family from New Orleans hired the young boy to work at their summer home. In the early twentieth century, African Americans could go only so far in school and when Jimmy completed the eighth grade, he moved with the Pond family to New Orleans. Through the Ponds, Jimmy met Lyle Saxon, editor of the Times-Picayune, and future biographer of Jean Lafitte. Saxon, hardly ten years Jimmy’s senior, purchased Jimmy’s first oils and canvas. Barthé’s biographer, Margaret Rose Vendryes, in “Barthé: A Life in Sculpture,” hypothesizes that the two shared an intimate relationship, though there is no certain evidence to support this. Saxon sent Jimmy on false errands to Delgado where he could view the school’s classical art collection, a collection not generally available to people of color. At twenty-three, Jimmy Barthé rendered a portrait of the Savior for a church bazaar which impressed Saxon. He attempted to have Jimmy enrolled in Delgado College - without success. Undeterred, and with the assistance of the local parish, Jimmy Barthé applied to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago accepted him. Had Barthé attended the Pennsylvania school, he would have matriculated with Walter Anderson. With a modest fellowship from the parish in New Orleans, Barthé took up residence in the home of his Aunt Rose in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. He attended night classes at the Art Institute and turned his attention to sculpture by accident. He was facing difficulties capturing the third dimension in his painting and an instructor suggested sculpting in clay. Classmates sat as models and Barthé created two busts. The transformation was complete. He was no longer Jimmy Barthé but Richmond Barthé (pronounced “bar-tay”). In 1927, Richmond Barthé exhibited in a show called The Negro in Art Week. Critics panned the show, but praised the success of Richmond’s two busts, and he drew the attention of Chicago’s philanthropists, notably Julian Rosenwald. With their encouragement, Richmond established a studio in Bronzeville and created the first of many opuses, among them “Tortured Negro” (1929) and “Black Narcissus" (1927). The former was modeled on the classical pose of St. Sebastian, who was tied to a tree/post and pierced with many arrows. The piece has been lost, according to Vendryes: “dimensions and location unknown.”

Inez Labat visited the Bronzeville studio in 1929. According the Celestine, Inez found Richmond Barthé eating canned beans and the “soles of his shoes were flapping.” Labat took the impoverished young Barthé to a cobbler and “gave him some change.” In gratitude Richmond sculpted Inez Labat, “La Mulatresse” (1929), in plaster and gave it to her.

That year Richmond Barthé received the first of two Rosenwald fellowships. With this money and funds he received from a successful one-man show, Richmond Barthé moved to New York City and into the heart of the thriving Harlem Renaissance. There, he met African American luminaries such as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Alaine Locke and Ralph Ellison. In New York, he became simply Barthé. Over the next twenty years, from studios in Harlem and in Greenwich Village, Barthé created his body of work and enjoyed success that the Jimmy Barthé could have only imagined. Barthé sold pieces to the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art as well as to wealthy collectors. He crafted “Blackberry Woman” (1930), his first major piece after moving to New York.

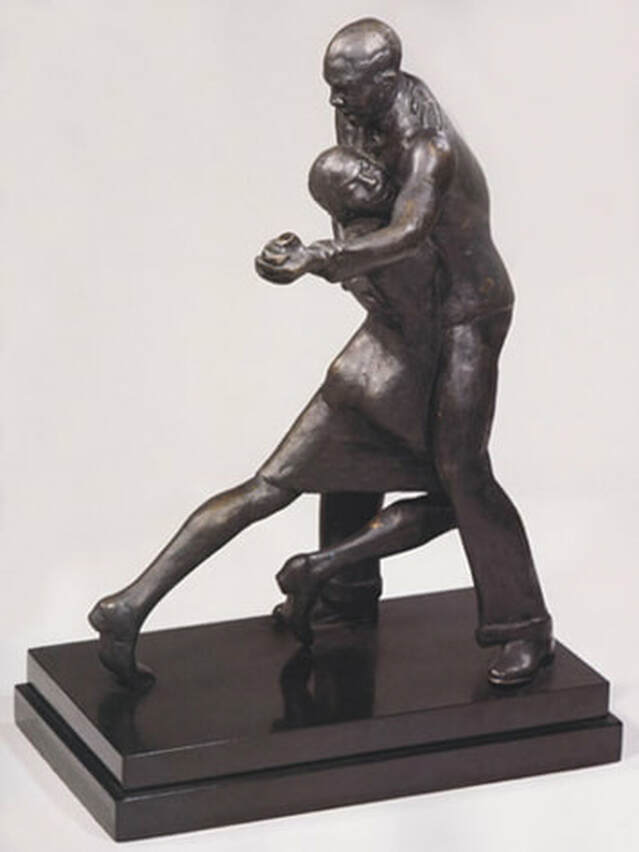

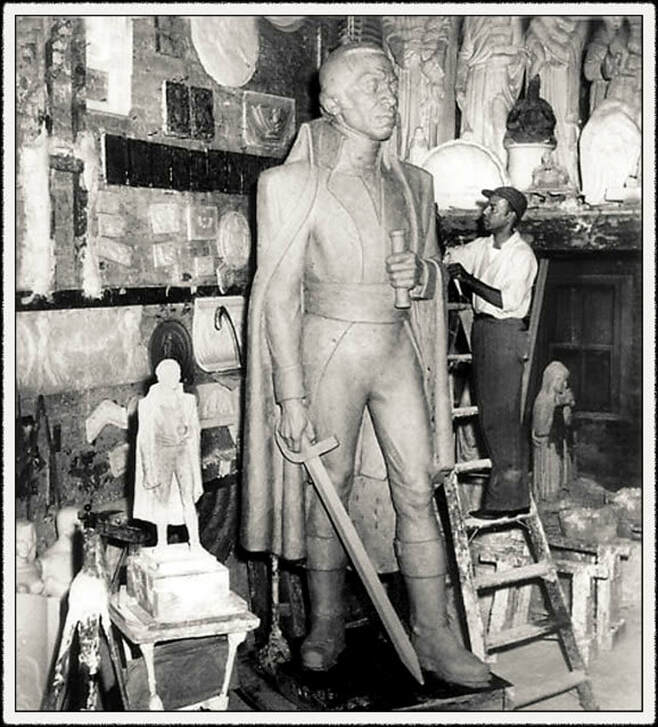

In 1935, Barthé exhibited at the Rockefeller Center alongside Matisse and Picasso. His sculptures, including “Feral Benga” (1935), “African Dancer” (1933), and “Wetta“ (1934), received more praise from critics than his more well-known contemporaries. Also in 1935, Barthé crafted his most political work to date. “The Mother” depicted a women holding the lifeless body of her son, the noose still hung about his neck. Sadly, Barthé, never comfortable as a dissident, later destroyed the piece. Barthé installed several public commissions, including a frieze in Harlem, “Exodus and Dance” (1940) and works for the James Weldon Thomas House. Dance and the music of the Savoy Club inspired much of his work, including “Rugcutters” (1930) and “Kolombwan” (1934). He also crafted several religious pieces, including a life-size statue of the Savior, “Come Unto Me“ (1947), commissioned by the St. Jude School in Montgomery, Alabama. In New York, Barthé also felt less confined in his sexuality. He crafted the homoerotic pieces “The Stevedore” (1937) and “Boy With a Flute” (1939). For reasons unclear, Barthé abandoned New York in 1949. He traveled with the wife of philanthropist Robert Lehman to her winter home in Jamaica, and shortly afterwards, he purchased an estate there, Iolaus. His time in Jamaica was unproductive. He tried to paint without success. He completed his two largest pieces, “Toussaint L’Ouvreture" (1952) and the equestrian “Dessaline" (1954), for the Haitian government’s sesquicentennial celebration, but he accomplished little else during his time in Jamaica. Iolaus was without power or telephone and his expatriate neighbors fled the hot and rainy summers. Loneliness and the slow pace of island life exacerbated an underlying depression. In 1961, he entered a hospital, first in Jamaica and then later in New York’s infamous Bellevue Hospital. Doctors diagnosed him with schizophrenia and he received shock treatment. He recovered enough to return to Jamaica but sold Iolaus in 1964. Unsure of where to turn, Barthé came home briefly, visiting his old teacher, Inez Labat. He received the keys to the city from then-Mayor Scafidi. Barthé spent several years in Florence, Italy, in the shadows of the Renaissance masters who had inspired his life’s work. Perhaps overwhelmed by the magnitude of Michelangelo, he could not work. He again became sick, and after a convalescence with friends in Lyon, France, arranged for return passage to the states. Penniless and ill, Barthé landed in Pasadena, California. He became the benefactor of patrons such as James Garner and Bill Cosby, although he ultimately sued the latter for casting statues without his permission. The City of Pasadena recognized the national treasure, and a street there is named for him. In the final photograph of the Vendryes biography, Barthé holds the street sign bearing his name. He smiles. Barthé died March 6, 1989, from complications related to cancer. St. Rose conducted a celebratory Mass and the bells rang in his honor. Barthés artistic legacy is complicated. Many African Americans disparage him as an “Uncle Tom,” for his many busts of famous men, including his last known piece, a bust of his patron, James Garner. He destroyed his most overtly political piece The Mother and may very well have destroyed Tortured Negro. He declined to permit the former to be displayed in the 1934 show, An Art Commentary on Lynching. The Creole Barthé was too high-minded, too formal for overtly political artists, such as Marcus Garvey. His formalism also set him apart from other modern sculptors. His work was too representational, too linked to the Renaissance to fit neatly among moderns such as Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. His harshest critics simply decry Barthé as an imitator, notable only for rising above the oppressive racism of his times. Vendryes, however, rightly notes that a Creole homosexual sculpting nude Africans and African-American models overtly challenged a white audience so fearful of African-American virility that they would (and often did) resort to violence to suppress it. Where Walter Anderson’s muse was the natural world and Ohr’s musen was pure form itself, Barthé reveled in the human body. He was not, as detractors argue, an apologist for whites in the separatist country of his birth. He longed for integration and advocated for it. However, politics was not his medium. It was the dancer, boxer, worker and the dying man. He treated them with dignity. Barthé, the artist said, “black is a color, not a race.” There is little remaining in Bay St. Louis to memorialize our greatest artist. A large pre-Katrina mural paying homage to the great artist was painted on the side of a county office building (on the corner of Second and Main Street), but the building was damaged by the storm and later demolished. The Bay St. Louis library houses a bust he gave to the city in 1964. Celestine Labat mentions a street off of Bookter named in his honor, but there is no Barthé or Barthe street found on the county’s Geoportal. Celestine Labat tells a story in Lori Gordon’s oral history. It is unclear when, but according to her, “Jimmy” Barthé was visiting one year at Christmas. A reveler came, and deep into his cups, the drunk man dropped and broke the plaster bust of Barthés first benefactor, Inez Labat. According to Labat, “We heard a crash from the parlor, and Barthé didn’t say anything, he just put his head in hands.” Years later, Celestine came into some money, and she sent Barthé the shards. He cast the piece, "La Mulatresse," in bronze and sent it to her, recouping only material costs and the foundry’s bill. Sources Vendryes, Margaret Rose, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture. University Press, 2008. Gordon, Lori K. “Oral History of Celestine Labat” Univ. of Southern Mississippi Oral History Project, 2003. Vertical Files, Hancock County Historical Society. Various Articles, Sun-Herald Archive. The Amistad Project. Tulane University.

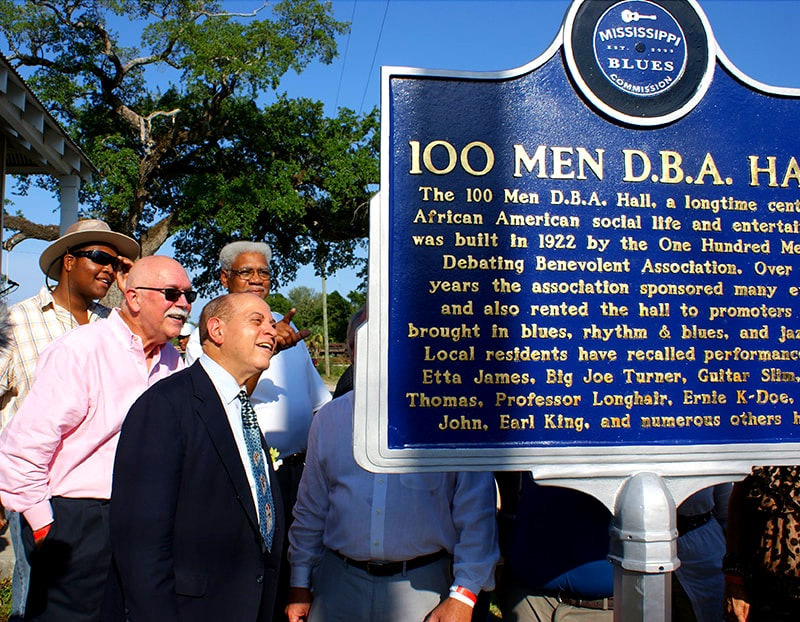

There's little solid historical information about one of Bay St. Louis's most significant buildings, but its new owner hopes to learn more with the help of long-time locals.

- story by Lisa Monti, photographs by Ellis Anderson

Dangermond plans to share with the public any photos and memorabilia she can track down. “I want to position the hall as an interpretive center,” she said. “My goal is to show how and why it came into existence and its significance to the area." According to the new 100 Men Hall website: In 1894, 12 civic-minded African American residents of Bay Saint Louis drew up the bylaws for an organization called the Hundred Members Debating Benevolent Association. The group’s primary purpose was to "assist its members when sick, bury its dead in a respectable manner and knit friendship." From an organizing group sprang an open-air pavilion and then, in 1922, a cornerstone was laid and the existing Hall built. The Hall was dedicated on July 16, 1923. The Mississippi Blues Trail marker at the entrance recognizes the 100 Men D.B.A. Hall for its significance as a music venue. B.B. King and Etta James were among the musicians and signers who took to the stage at the hall. Money raised by the performances was used by the organization to help members of the community get medical treatment and other services.

Saved from demolition by previous owners and guardians Kerry and Jesse Loya, the refurbished hall hosted concerts, weddings, Sunday afternoon Cajun dances and pop-up dinners over the last several years.

In the short time she’s owned the property, Dangermond has held a writer’s workshop and a Baria for Congress fundraising performance by Cedric Burnside. More events are in the works while Dangermond seeks pieces of the hall’s history. “I’ve reached out to some folks to see if they have any old family photos. They might have one of their mom or an aunt standing in front of the hall. Up until Camille, if you were African American, you went to that hall. That’s where events were held. So there must be photos out there.”

There’s a sense of urgency to locate any photos and other keepsakes and record memories as the years go by, she said.

“Any memorabilia, even if it’s story, I’m very interested,” she said. To contact Dangermond, email [email protected]or call (415) 336-9543.

In July, the Cedar Point area's contributions to Bay St. Louis were recognized by a state historical marker, while one of the neighborhood's beloved gathering spots is undergoing a renewal.

- story by Denise Jacobs

Kersanac remembered those “coming to a new world” to work at Peerless Oyster Company from places as far away as France, Germany, Italy, and South America. They were, Ms. Kersanac noted, “starting from scratch,” and, she added poignantly, “We are the glad recipients of all their labor.”

Markers of other types - indicators, perhaps - can be found in Cedar Point, as well. Larroux Park, at the corner of Dunbar Avenue and Julia Street, is one such community touchstone. Thanks to grant funding from Hancock County, the green space now boasts new swings and slides. The park is completely fenced and includes a basketball court and an old gazebo. One very heavy picnic table rests in the shade of an old oak tree that is rooted in the yard next door, but is no respecter of fences.

Additional Larroux Park projects in the works include park benches and trash-can container painting by Hancock Youth Leadership Academy (HYLA) teens. Josh Cothern and Charlie Luttrell, Cedar Point teens, planted a Bradford Pear tree at Larroux Park in late July as Charlie's HYLA project. The duo and a handful of friends are committed to watering and caring for the tree in its early days.

The park is located near the site of a popular grocery store that no longer exists. According to one Larroux family source, Ed Larroux first installed playground equipment in the early fifties, soon after he purchased what became the Mercadel grocery store, so children could entertain themselves while their parents shopped. In a 2016 Shoofly Magazine article, local historian Pat Murphy recalls that after owning the grocery only a few years, Ed Larroux converted the building into a warehouse, with a place in the front for neighborhood kids to play ping-pong and pool.

All this property later became Larroux Park as gifted by Ed Larroux via a 99-year-lease.

The merry-go-round is long gone, and the old (newly-replaced) swings had rusted with age, but the park remains. On any given fall or winter day after school has ended, a group of high school boys of various shapes, sizes, and ethnicities can be found playing a game of pick-up basketball.

It’s a happy sight, and one that reminds us of the resiliency of neighborly bonds and the strength of community. For this we are glad recipients. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed