For nearly a century, this Waveland seaside retreat has offered education, spiritual enrichment and recreational opportunities to people of color and surrounding communities.

- by Wendy Sullivan - photos courtesy Hancock County Historical Society and Wendy Sullivan

A new documentary by a Pass Christian filmmaker takes an unflinching look behind the scenes of a five-year statewide battle.

- by Ellis Anderson

Sycamore Street, formerly home to several popular juke joints, used to hum with music and good times. Take a spin around the dance floor in this look back in time.

- Story by Rachel Dangermond

Our local music historian waxes nostalgic about the Bay St. Louis of his youth, and how local bands influenced his life.

- story by Pat Murphy

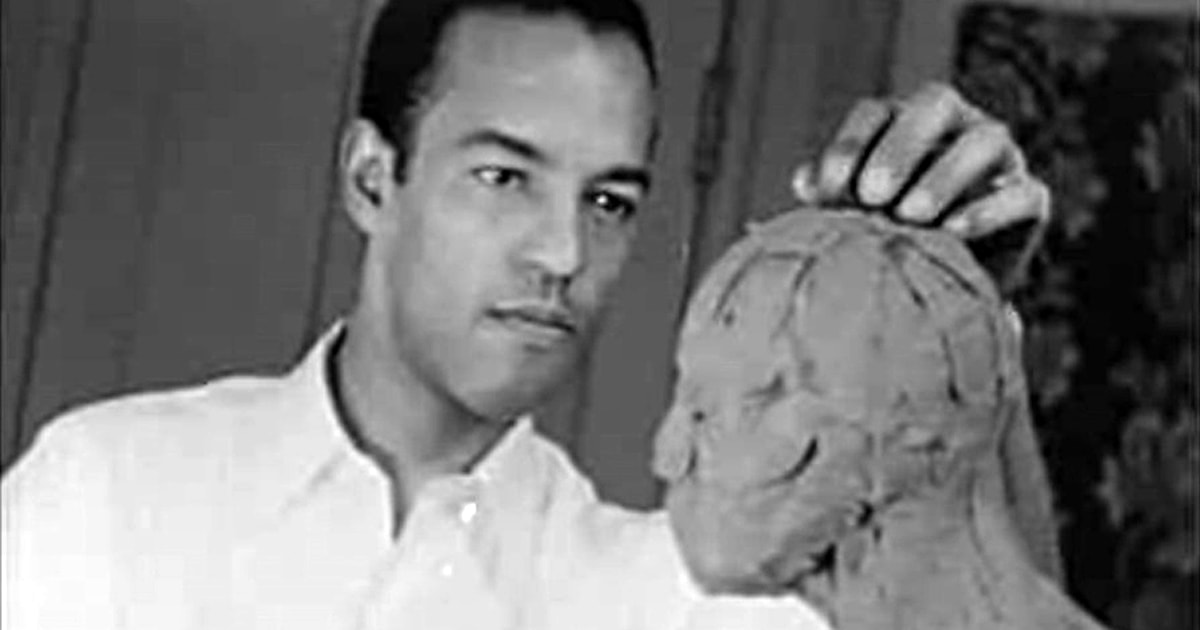

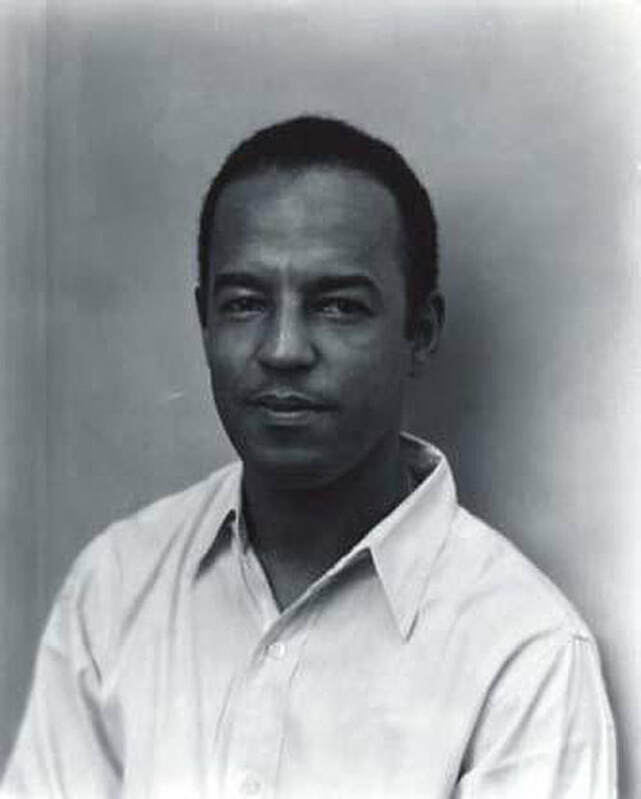

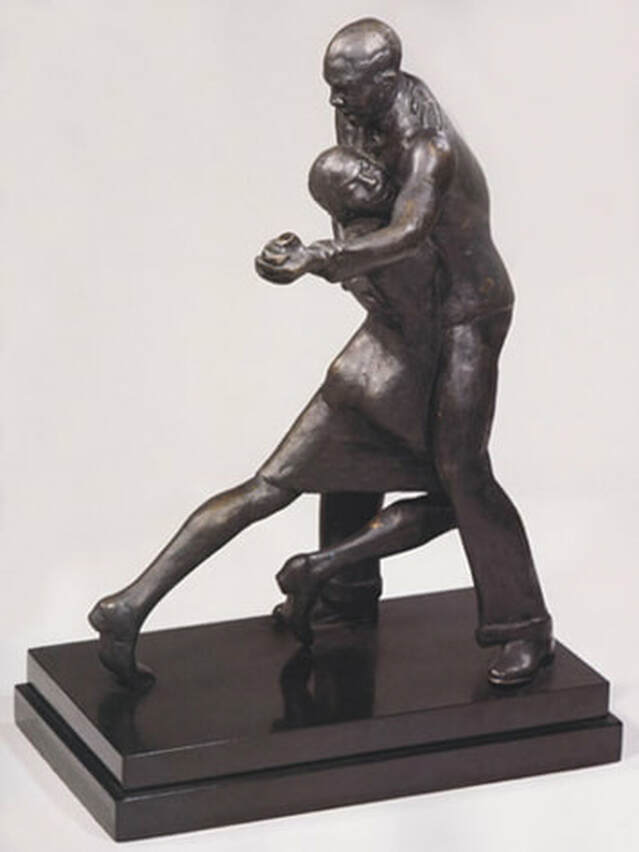

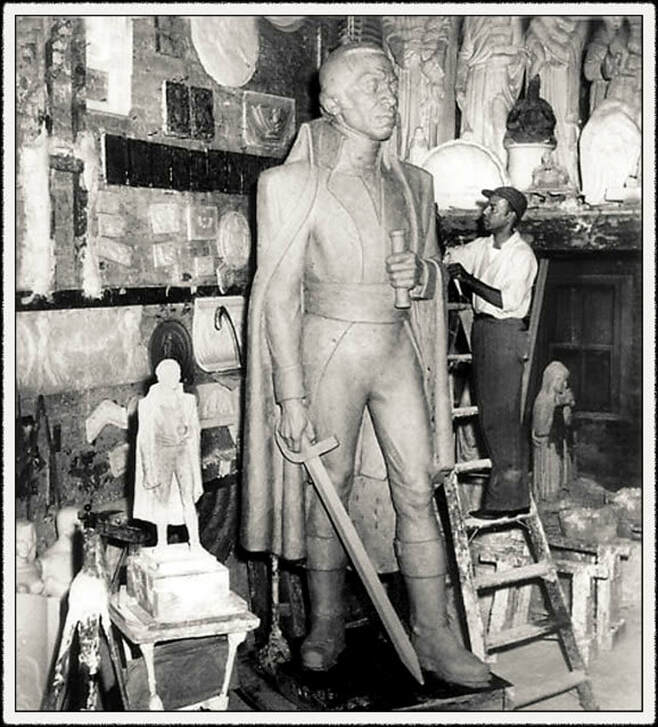

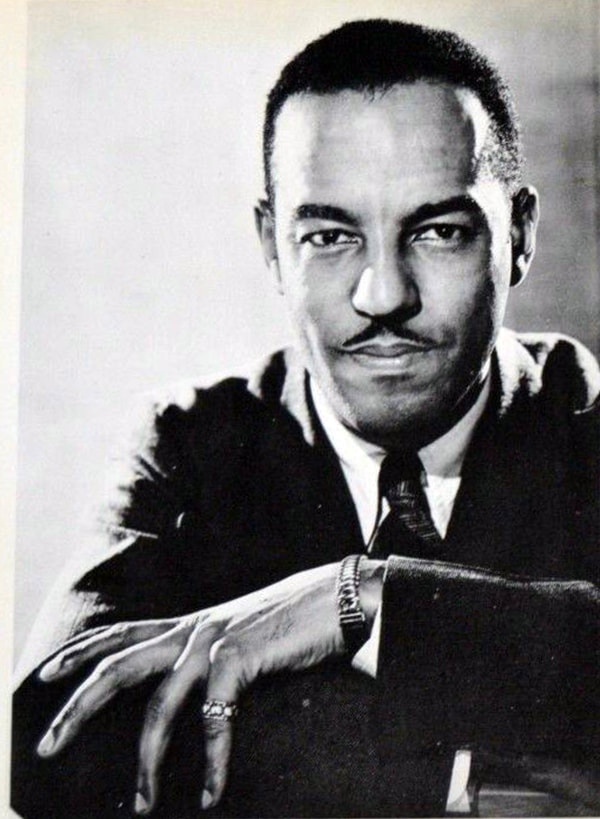

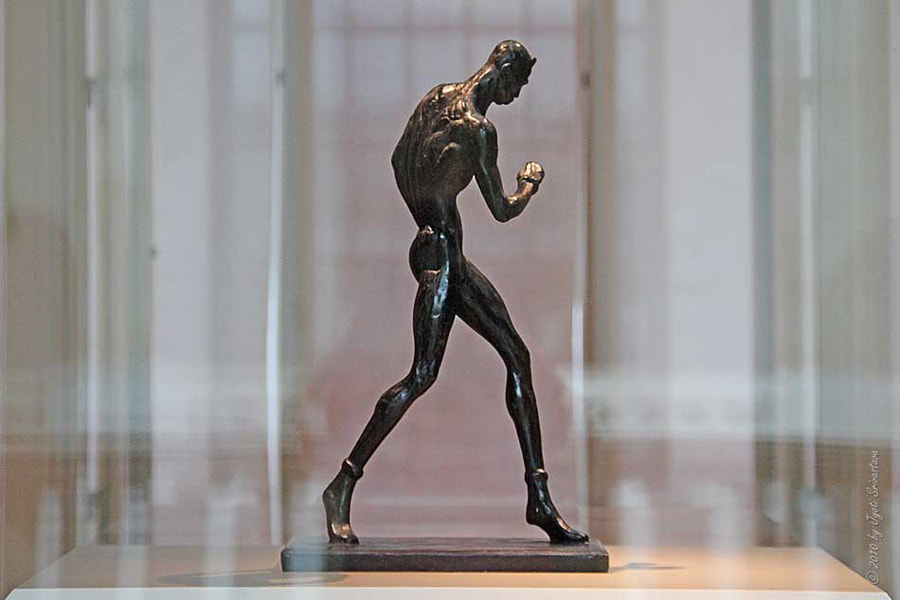

Richmond Barthé left Bay St. Louis at age fourteen. He became one of 20th century America’s greatest sculptors of the human form - and Mississippi’s preeminent artist in the field.

- story by Edward Gibson

According to Celestine Labat, in the oral history preserved by Lori Gordon, Barthé was pronounced like “hearth.” His mother, the Creole Clemente’ Rabateau, hailed from a family of craftsmen, and his father, Richmond Barthé, an “American” as the Creoles disparaged, was a dark-skinned, grey-eyed African-American. The elder Richmond died within months of Jimmy’s birth.

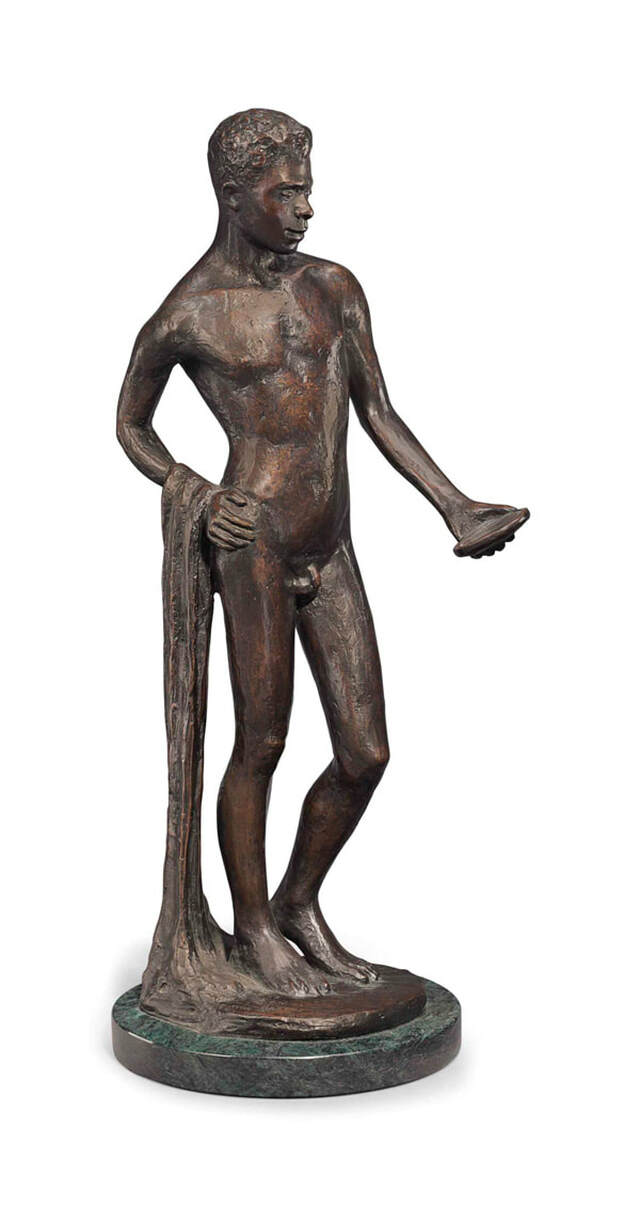

Jimmy enrolled at the newly formed St. Rose school where he met Celestine Labat’s sister, Inez Labat. The teacher Labat recognized Jimmy’s talent for drawing and encouraged him with both praise and a supply of pencils and paper. Inez Labat encouraged the young artist throughout his life. Jimmy’s talent for portraiture soon drew the attention of the town, and the Pond family from New Orleans hired the young boy to work at their summer home. In the early twentieth century, African Americans could go only so far in school and when Jimmy completed the eighth grade, he moved with the Pond family to New Orleans. Through the Ponds, Jimmy met Lyle Saxon, editor of the Times-Picayune, and future biographer of Jean Lafitte. Saxon, hardly ten years Jimmy’s senior, purchased Jimmy’s first oils and canvas. Barthé’s biographer, Margaret Rose Vendryes, in “Barthé: A Life in Sculpture,” hypothesizes that the two shared an intimate relationship, though there is no certain evidence to support this. Saxon sent Jimmy on false errands to Delgado where he could view the school’s classical art collection, a collection not generally available to people of color. At twenty-three, Jimmy Barthé rendered a portrait of the Savior for a church bazaar which impressed Saxon. He attempted to have Jimmy enrolled in Delgado College - without success. Undeterred, and with the assistance of the local parish, Jimmy Barthé applied to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago accepted him. Had Barthé attended the Pennsylvania school, he would have matriculated with Walter Anderson. With a modest fellowship from the parish in New Orleans, Barthé took up residence in the home of his Aunt Rose in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. He attended night classes at the Art Institute and turned his attention to sculpture by accident. He was facing difficulties capturing the third dimension in his painting and an instructor suggested sculpting in clay. Classmates sat as models and Barthé created two busts. The transformation was complete. He was no longer Jimmy Barthé but Richmond Barthé (pronounced “bar-tay”). In 1927, Richmond Barthé exhibited in a show called The Negro in Art Week. Critics panned the show, but praised the success of Richmond’s two busts, and he drew the attention of Chicago’s philanthropists, notably Julian Rosenwald. With their encouragement, Richmond established a studio in Bronzeville and created the first of many opuses, among them “Tortured Negro” (1929) and “Black Narcissus" (1927). The former was modeled on the classical pose of St. Sebastian, who was tied to a tree/post and pierced with many arrows. The piece has been lost, according to Vendryes: “dimensions and location unknown.”

Inez Labat visited the Bronzeville studio in 1929. According the Celestine, Inez found Richmond Barthé eating canned beans and the “soles of his shoes were flapping.” Labat took the impoverished young Barthé to a cobbler and “gave him some change.” In gratitude Richmond sculpted Inez Labat, “La Mulatresse” (1929), in plaster and gave it to her.

That year Richmond Barthé received the first of two Rosenwald fellowships. With this money and funds he received from a successful one-man show, Richmond Barthé moved to New York City and into the heart of the thriving Harlem Renaissance. There, he met African American luminaries such as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Alaine Locke and Ralph Ellison. In New York, he became simply Barthé. Over the next twenty years, from studios in Harlem and in Greenwich Village, Barthé created his body of work and enjoyed success that the Jimmy Barthé could have only imagined. Barthé sold pieces to the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art as well as to wealthy collectors. He crafted “Blackberry Woman” (1930), his first major piece after moving to New York.

In 1935, Barthé exhibited at the Rockefeller Center alongside Matisse and Picasso. His sculptures, including “Feral Benga” (1935), “African Dancer” (1933), and “Wetta“ (1934), received more praise from critics than his more well-known contemporaries. Also in 1935, Barthé crafted his most political work to date. “The Mother” depicted a women holding the lifeless body of her son, the noose still hung about his neck. Sadly, Barthé, never comfortable as a dissident, later destroyed the piece. Barthé installed several public commissions, including a frieze in Harlem, “Exodus and Dance” (1940) and works for the James Weldon Thomas House. Dance and the music of the Savoy Club inspired much of his work, including “Rugcutters” (1930) and “Kolombwan” (1934). He also crafted several religious pieces, including a life-size statue of the Savior, “Come Unto Me“ (1947), commissioned by the St. Jude School in Montgomery, Alabama. In New York, Barthé also felt less confined in his sexuality. He crafted the homoerotic pieces “The Stevedore” (1937) and “Boy With a Flute” (1939). For reasons unclear, Barthé abandoned New York in 1949. He traveled with the wife of philanthropist Robert Lehman to her winter home in Jamaica, and shortly afterwards, he purchased an estate there, Iolaus. His time in Jamaica was unproductive. He tried to paint without success. He completed his two largest pieces, “Toussaint L’Ouvreture" (1952) and the equestrian “Dessaline" (1954), for the Haitian government’s sesquicentennial celebration, but he accomplished little else during his time in Jamaica. Iolaus was without power or telephone and his expatriate neighbors fled the hot and rainy summers. Loneliness and the slow pace of island life exacerbated an underlying depression. In 1961, he entered a hospital, first in Jamaica and then later in New York’s infamous Bellevue Hospital. Doctors diagnosed him with schizophrenia and he received shock treatment. He recovered enough to return to Jamaica but sold Iolaus in 1964. Unsure of where to turn, Barthé came home briefly, visiting his old teacher, Inez Labat. He received the keys to the city from then-Mayor Scafidi. Barthé spent several years in Florence, Italy, in the shadows of the Renaissance masters who had inspired his life’s work. Perhaps overwhelmed by the magnitude of Michelangelo, he could not work. He again became sick, and after a convalescence with friends in Lyon, France, arranged for return passage to the states. Penniless and ill, Barthé landed in Pasadena, California. He became the benefactor of patrons such as James Garner and Bill Cosby, although he ultimately sued the latter for casting statues without his permission. The City of Pasadena recognized the national treasure, and a street there is named for him. In the final photograph of the Vendryes biography, Barthé holds the street sign bearing his name. He smiles. Barthé died March 6, 1989, from complications related to cancer. St. Rose conducted a celebratory Mass and the bells rang in his honor. Barthés artistic legacy is complicated. Many African Americans disparage him as an “Uncle Tom,” for his many busts of famous men, including his last known piece, a bust of his patron, James Garner. He destroyed his most overtly political piece The Mother and may very well have destroyed Tortured Negro. He declined to permit the former to be displayed in the 1934 show, An Art Commentary on Lynching. The Creole Barthé was too high-minded, too formal for overtly political artists, such as Marcus Garvey. His formalism also set him apart from other modern sculptors. His work was too representational, too linked to the Renaissance to fit neatly among moderns such as Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. His harshest critics simply decry Barthé as an imitator, notable only for rising above the oppressive racism of his times. Vendryes, however, rightly notes that a Creole homosexual sculpting nude Africans and African-American models overtly challenged a white audience so fearful of African-American virility that they would (and often did) resort to violence to suppress it. Where Walter Anderson’s muse was the natural world and Ohr’s musen was pure form itself, Barthé reveled in the human body. He was not, as detractors argue, an apologist for whites in the separatist country of his birth. He longed for integration and advocated for it. However, politics was not his medium. It was the dancer, boxer, worker and the dying man. He treated them with dignity. Barthé, the artist said, “black is a color, not a race.” There is little remaining in Bay St. Louis to memorialize our greatest artist. A large pre-Katrina mural paying homage to the great artist was painted on the side of a county office building (on the corner of Second and Main Street), but the building was damaged by the storm and later demolished. The Bay St. Louis library houses a bust he gave to the city in 1964. Celestine Labat mentions a street off of Bookter named in his honor, but there is no Barthé or Barthe street found on the county’s Geoportal. Celestine Labat tells a story in Lori Gordon’s oral history. It is unclear when, but according to her, “Jimmy” Barthé was visiting one year at Christmas. A reveler came, and deep into his cups, the drunk man dropped and broke the plaster bust of Barthés first benefactor, Inez Labat. According to Labat, “We heard a crash from the parlor, and Barthé didn’t say anything, he just put his head in hands.” Years later, Celestine came into some money, and she sent Barthé the shards. He cast the piece, "La Mulatresse," in bronze and sent it to her, recouping only material costs and the foundry’s bill. Sources Vendryes, Margaret Rose, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture. University Press, 2008. Gordon, Lori K. “Oral History of Celestine Labat” Univ. of Southern Mississippi Oral History Project, 2003. Vertical Files, Hancock County Historical Society. Various Articles, Sun-Herald Archive. The Amistad Project. Tulane University.

With a historic building and a beloved choir that are known throughout the region, "St. Rose," is approaching its 100th birthday in the Bay!

- story by Denise Jacobs, photos by Ellis Anderson

Joan Thomas Joan Thomas

Known as one of the church’s historians, Joan Thomas notes that it was “pretty amazing” during that era for someone with Labat’s cabinet-making background to rise to the status of architect. Thomas, is well-suited to her current position as director of religious education at St. Rose de Lima: the now-retired educator chaired the history department for the Bay-Waveland School District and was named Wal-mart Teacher of the Year in 1999. She also served as a member of the Bay-Waveland School Board.

Thomas remembers having the opportunity to look underneath the church years later during a restoration project and finding two names carved in foundation braces: Jellicoe and Lewis—no last names. Thomas assumes these were two of the construction workers from the 1920s. The 40’ x 80’ foot church, built to accommodate 350 people, was completed in 1926. Shortly thereafter, St. Rose de Lima Parish was made independent of Our Lady of the Gulf Parish. Ms. Thomas explains that the land for the church came from the St. Augustine Seminary, and it was the seminary, the Order of the Society of the Divine Word, that provided clergy to St. Rose de Lima Parish, beginning with Father Francis Baltes, SVD. The Divine Word continues to provide clergy to this day - 21 thus far. Thomas points out that each has worked at “enhancing the diversity of the parish.”

On Installation Day in 1926, Bishop Richard Oliver Gerow commented on the beauty of the altar cloths, which had been made by the parish women. In the building of the church, parish families “put up money, and the ladies cooked meals.”

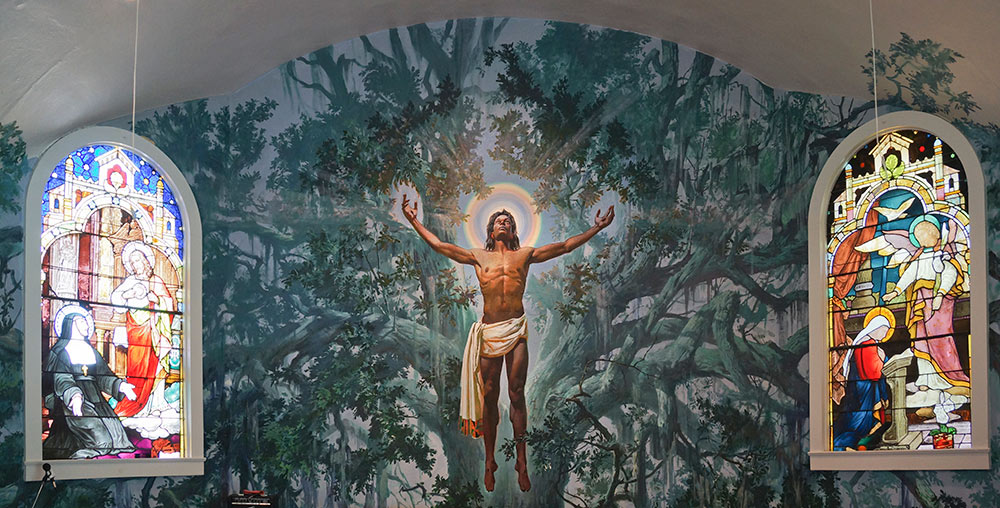

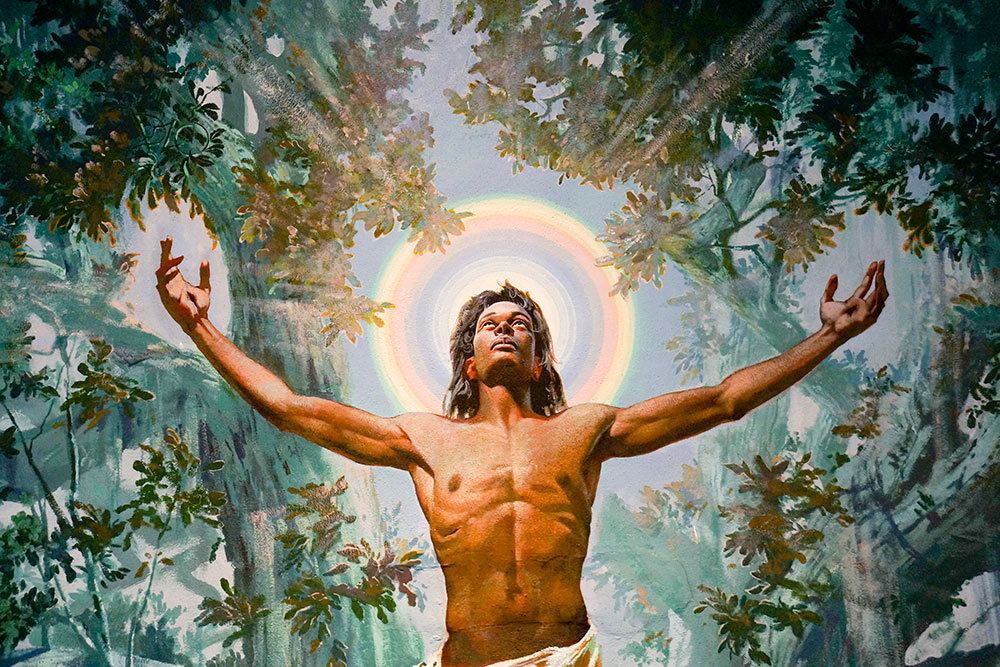

Thomas describes the construction of the church as “a community effort for the black congregants to have something of their own,” explaining that an “astonishing number of black catholics” lived in the area. “They needed a place of their own,” Thomas says, “a sense of full acceptance.” Years later, after sixty years of faithful service, the original church building’s interior and exterior were in need of repair. This renovation began in the late 1980s and early 1990s under the direction of Father Kenneth Hamilton, SVD, pastor. The project included the creation of the nationally-recognized work of art that still stands behind the altar, the “Christ in the Oak” mural. The altar, ambo, tabernacle, and table are all carved from local wood retrieved from the Bay. Master woodworker Ellsworth Collins, who passed away in 1996 after spending his life in Bay St. Louis, crafted the altar from an extraordinary rooted stump found near St. Stanislaus College. The wooden altar base appears to be reaching toward heaven. “Christ in the Oaks,” was painted by Armenian artist Auseklis Ozols, founder of the New Orleans Academy of Fine Art. As recorded in Mississippi Back Roads:Notes on Literature and History(Elmo Howell), Ozols envisioned a mural that would represent both the Crucifixion and the Resurrection: “The figure of Christ hangs in the air, behind him the tree, the Cross, the symbol of the earth mightily grasping the ground. But Christ has broken free! The tree is behind him, yet it is his burden also.” Local artist Kat Fitzpatrick, at the time, a member of the St. Rose gospel choir - and one of Ozol’s students – originally introduced the artist to the priest and helped the mural process along. Thomas explains that the mural’s black Christ is intended to reflect the Afro-centric nature of the church. “It was Father Ken,” she recalls, “who moved us in the direction the church is in now. I guess he kind of took a page from Pope John Paul II, who said that ‘Faith that does not become culture is not wholly embraced, fully thought, or faithfully lived.’”

Father Kenneth introduced the St. Rose de Lima parish to the concept of re-rooting and re-routing in Christ.

“Since Vatican II,” Thomas notes, “we knew we all played a role in the church. We all have a job to do. We all had a function, but I think it’s when Father Ken came here, 20 years after Vatican II, that we found real ownership of our parish and our culture. “Father Ken used to remind us that we had to remember ‘who we were and whose we were.’ People come to us for a reason and a season. And Father Ken re-rooted and re-routed us. Everybody wanted that.” The pastor also led congregants into an ongoing practice of oral history. Ms. Thomas remembers one of the things she “most loved” about Father Ken: “At each mass, Father Ken called upon people within the congregation to stand up and tell their family history, tell a bit about their family’s journey. We were also tasked with one more thing. Everybody had to go back to the family homestead and bring back to church a teaspoon or so of dirt—soil. It was placed in a wooden communal bowl with a lid on it. And at funerals, we used to stir the soil. Stir the soil. It was very meaningful. It was powerful. It was visual. It took us back to our Afro-centric roots.”

The next major work at 301 South Necaise Avenue took place in the aftermath of Katrina. Actually, the church fared relatively well, all things considered. According to church archives, the priest assigned to St. Rose at the time, Father Sebastian Myladiyal, SVD, prayed the sacrament, “To Avert the Storm,” as Hurricane Katrina approached.

Myladiyal then waited out the storm at a nearby building on the highest ground in Bay St. Louis. When he arrived at the church the next morning, some windows were blown in and there was roof damage but, amazingly, no water had damaged the half of the church containing the altar and mural. In the aftermath of Katrina, St. Rose became a distribution center for provisions and supplies for people in need, including but extending well beyond the parish membership, most in need themselves—you might say, re-rooting and re-routing once again. Today, St. Rose de Lima is a vibrant and diverse parish heavily influenced by the African-American culture. The church’s dynamic full gospel choir is known nationwide. Visitors travel from around the country to tour the church, and many light candles for loved ones, admire the church’s craftsmanship, and enjoy the serenity of their surroundings. According to Ms. Thomas, St. Rose counts 409 families as members, enough to warrant three weekly services. There’s a service at 4pm on Saturday and two on Sunday mornings at 7am and 9am, with Jim Collins, (the 2018 Hancock County Citizen of the Year) leading the singing at the earlier service.

In July, the Cedar Point area's contributions to Bay St. Louis were recognized by a state historical marker, while one of the neighborhood's beloved gathering spots is undergoing a renewal.

- story by Denise Jacobs

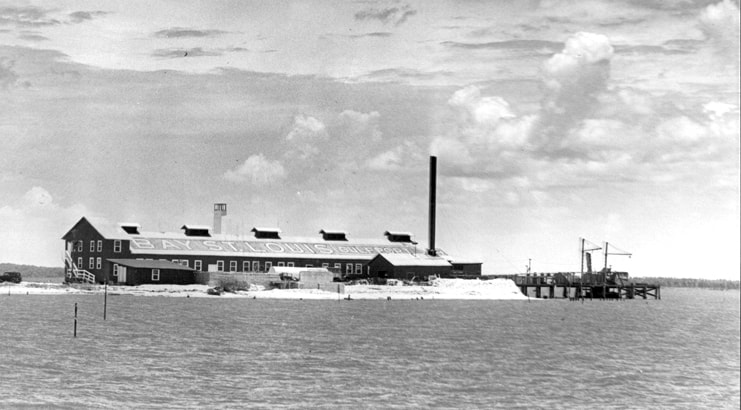

Kersanac remembered those “coming to a new world” to work at Peerless Oyster Company from places as far away as France, Germany, Italy, and South America. They were, Ms. Kersanac noted, “starting from scratch,” and, she added poignantly, “We are the glad recipients of all their labor.”

Markers of other types - indicators, perhaps - can be found in Cedar Point, as well. Larroux Park, at the corner of Dunbar Avenue and Julia Street, is one such community touchstone. Thanks to grant funding from Hancock County, the green space now boasts new swings and slides. The park is completely fenced and includes a basketball court and an old gazebo. One very heavy picnic table rests in the shade of an old oak tree that is rooted in the yard next door, but is no respecter of fences.

Additional Larroux Park projects in the works include park benches and trash-can container painting by Hancock Youth Leadership Academy (HYLA) teens. Josh Cothern and Charlie Luttrell, Cedar Point teens, planted a Bradford Pear tree at Larroux Park in late July as Charlie's HYLA project. The duo and a handful of friends are committed to watering and caring for the tree in its early days.

The park is located near the site of a popular grocery store that no longer exists. According to one Larroux family source, Ed Larroux first installed playground equipment in the early fifties, soon after he purchased what became the Mercadel grocery store, so children could entertain themselves while their parents shopped. In a 2016 Shoofly Magazine article, local historian Pat Murphy recalls that after owning the grocery only a few years, Ed Larroux converted the building into a warehouse, with a place in the front for neighborhood kids to play ping-pong and pool.

All this property later became Larroux Park as gifted by Ed Larroux via a 99-year-lease.

The merry-go-round is long gone, and the old (newly-replaced) swings had rusted with age, but the park remains. On any given fall or winter day after school has ended, a group of high school boys of various shapes, sizes, and ethnicities can be found playing a game of pick-up basketball.

It’s a happy sight, and one that reminds us of the resiliency of neighborly bonds and the strength of community. For this we are glad recipients.

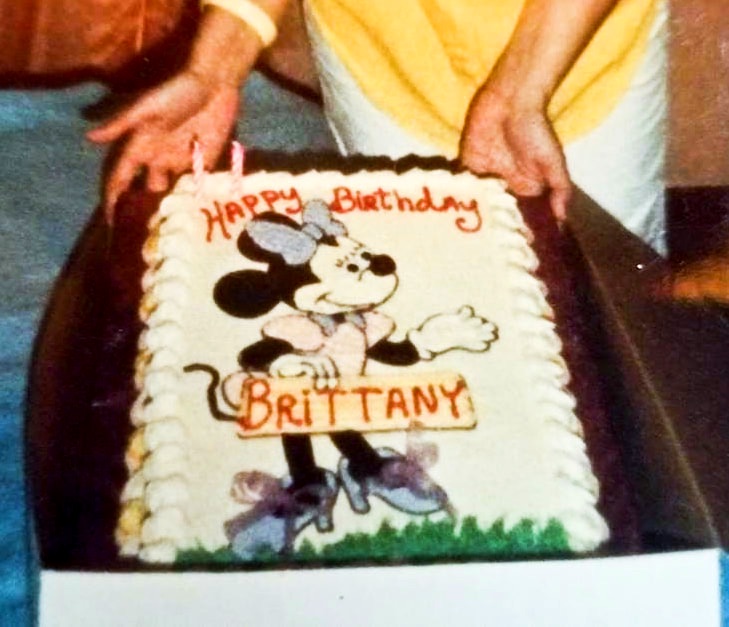

The sugary Southern tradition of baking artful - and delectable - cakes for special occasions is celebrated in this story looking back at some of the town's best bakers.

- story by Denise Jacobs

Still, beloved as she was, Ruth Thompson, owner of Ruth’s Cakery in Bay St. Louis, was just one of several cherished cake makers in the Bay St. Louis/Waveland area. And there was Inez Blaize Favre (1900-1983). In the ‘60s, Inez and daughters Udell and Inez—or “Little Inez” as she was known—baked from their house on Felicity Street. Little Inez became Inez Favre Pope. She baked from her home on Highland Drive in her retirement from the late ‘80s until Katrina destroyed the house. Rachel Pope Cross, one of Mrs. Pope’s daughters, remembers her father building a special kitchen on the back of the house to have a proper home bakery. “A delicacy was always in the oven,” Mrs. Cross said, “and friends and neighbors popped in almost every day of the year to pick up their sweet treats.” Mrs. Cross remembers her mother baking over 500 petit fours for the opening of a Biloxi casino. “It fell to me to put dots on sugar cubes to resemble dice.”  One of the red velvet cakes that the family still traditionally serves on Christmas day. Photo courtesy Danita Luttrell One of the red velvet cakes that the family still traditionally serves on Christmas day. Photo courtesy Danita Luttrell

Danita Scianna Luttrell, another of Inez Blaize Favre’s 40+ grandchildren, remembers her Aunt Udell as the master decorator. “Aunt Udell once baked a five-foot tall lighthouse for a Hancock Bank anniversary; I can still see it sitting in the lobby of Hancock Bank down on the beach.”

Both Luttrell and Cross remember customers bringing party-themed napkins to Little Inez and Udell. Danita or Rachel would transfer the design onto the cake with a toothpick, and the bakers would fill it in with icing or hollowed-out sugar mold designs. As the girls tell it, all the relatives got in on the act at one point or another by washing mounds of mixing bowls, delivering cakes, or answering the front door. Luttrell remembers her grandmother as an amazing cook and a woman who did everything to perfection. “She would spend more money making something perfect than she made selling it!” Luttrell attributes this to a convent-based education. “She just wanted everything to be beautiful, and she passed down all her talents, from cookery to crewel to cakery, to her children and grandchildren.”

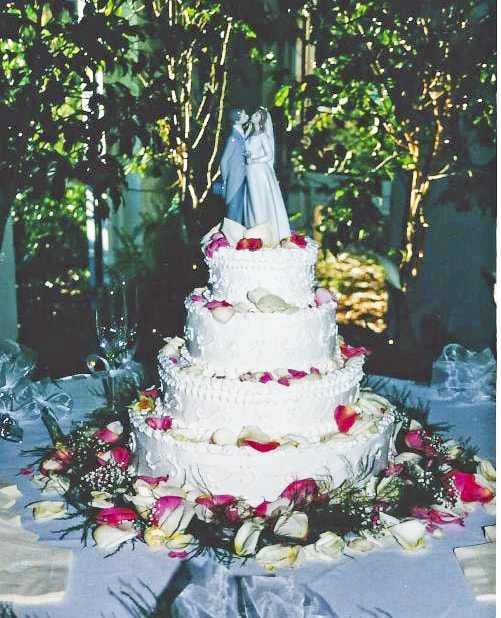

L: wedding cake by Inez Favre Pope for daughter Rachel Cross. Top R: wedding cake for Inez Favre Pope made by Inez Favre. Lower R: cake by Inez Favre Pope for Rachel Cross's daughter. Photos courtesy Rachel Cross

Other cake bakers in the Inez line include Laurin LaFontaine, daughter of one of Inez Blaize Favre’s sons. LaFontaine baked from the mid-1970s through the late ‘90s. Also, Mary Ann Benvenutti, another grandchild, began baking out of her home in the late 1980s. Benvenutti no longer bakes except for special family events. At Christmas, her red velvet cake graces the family dinner table.

Luttrell said that all the women have Inez Blaize Favre’s cake recipes but are sworn to secrecy. “The red velvet cake frosting was not the typical cream cheese type,” she says. “It was almost like a whipped cream, but it’s not whipped cream.”

More cakes by Inez Farve's descendants: Top left - Moana cake by Paul Scianna, top right, graduation cake by Mary Ann Scianna Benvenutti, Car birthday cake (center) by Mary Ann Scianna Benvenutti, lower left - chocolate cake by Laurie Benvenutti, lower right - Berry Chantilly cake by Laurie Benvenutti. Photos courtesy Danita Scianna Luttrell

Women were not the only ones working the cake angle. Other FB commenters mentioned Gregory Morreale, who is said to have made birthday, holiday, and christening cakes that were works of art.

While it is likely that Katrina washed away many photographs of cake-worthy occasions—and there were many—our fondest memories are intact, right down to the aroma of delicate vanilla and warm butter baking, a cake’s soft velvety texture, and the distinctive and delicious taste of childhood—an essence we have never quite been able to replicate.

Special thanks to "You Know You're From the Bay" Facebook page and contributors.

A new grassroots group seeks to support both the Bay St. Louis Historic District and the volunteer commission that oversees it.

- by Grace Wilson

The Bay St. Louis Historic District, created after Hurricane Katrina with the overwhelming support of property owners within its boundaries, helps preserve the city’s unique ambiance and charm. It’s overseen by a Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) made up of volunteers, each with experience in some relevant field – history, restoration, architecture, real estate and construction.

Now there's a grass-roots group to support both the district and the HPC, the Bay St. Louis Historic District Supporters (BSLHDS). It was started this spring by Ellis Anderson, publisher of the Shoofly Magazine. Anderson served on the HPC for five years and was its co-chairman until May. She's also a board member of Mississippi Heritage Trust. Earlier this year, Anderson began hearing rumors of a behind-the-scenes effort by some elected officials to dissolve the HPC. When she began organizing a defense, she was abruptly dismissed from the HPC by the council. The Supporters group is a continuation of her efforts to preserve the group that helps preserve the city. In the first few weeks after establishment, the group garnered 400 followers/members as word spread about its Facebook page (see BSL Historic District Supporters) and website. The Bay St. Louis Historic District Supporters (BSLHDS) website calls historic Bay St. Louis the place “where good things come together.” The group connects the dots between economic development, quality of life and community heritage engendered by the district. There are no dues and no meetings. Information is relayed to members as threats to the district or positive news about the district occurs. The website encourages citizens to attend the public meetings by posting the schedule and agendas. Basic information about the district itself is also made available so people can learn more about this valuable city asset. “Property values in the historic district of Old Town Bay St. Louis are the highest and most desirable along the coast,” said Terie Velardi, a group member and a state certified appraiser. Velardi was also instrumental in helping create the district and served on the HPC for several years. “Historic preservation is a significant component in support of property values and the character of Old Town,” said Velardi. “The blending of the old and thoughtful new development protects and enhances the interest and value of all properties.” Lolly Rash agrees that new development can complement the historic district. “By setting the bar high, you get better development,” Rash said. “Bay St. Louis is not a blank slate. It has a unique character. If you’re smart about developing, you are respectful of that fabric.”

The city charges the volunteers of the HPC to oversee all building within the district. Applicants for most building permits within the district also submit applications to the HPC. The HPC is an advisory board that meets monthly and oversees about 150 applications each year. New building projects – whether restorations or new construction within the district - are brought before the commission while they’re still in the planning phase.

At the monthly public meetings, the commission refers to the written, adopted design guidelines while inspecting the plans. The majority pass through without issue. A few are passed with stipulations. On rare occasions, a property owner will disagree with the commission’s decision and appeal to the city council. In the past five years, only six property owners have opted to appeal the commission’s decisions.

The supporters’ website credits this less than one percent appeal record on the fact that the BSL HPC “has a long-standing reputation for ‘going by the book.’ Decisions are based on written guidelines adopted by the city, not politics or the personal preferences of commissioners.” The BSLHDS website also points out that the Historic District Design Guidelines are akin to the covenants property owners must adhere to when they buy into upscale neighborhoods. Property values are protected from unsightly/inappropriate development, which offsets any minor inconvenience at having to apply for an additional permit. While property values and economic development are the backbone benefits of historic preservation districts across the country, honoring community heritage plays a part as well.  Lolly Rash, executive director of Mississippi Heritage Trust Lolly Rash, executive director of Mississippi Heritage Trust

Rash recalled post-Katrina Bay St. Louis as a place where residents were determined to preserve the remaining historic buildings that had survived the devastating hurricane (the city lost hundreds during the storm). “I remember very vividly the lead-up to the original ordinances and how passionate the community was on these historic priorities,” Rash said. “But citizens need to continue to let elected officials know how important their community character is.” She continued, “It can be discouraging when you feel like you don’t have a voice or you feel like you’re being dismissed, but you have to step up and stand for what you believe is important in your community.”

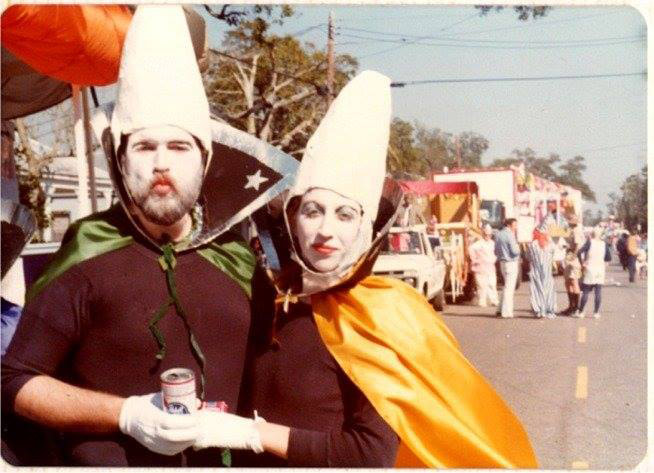

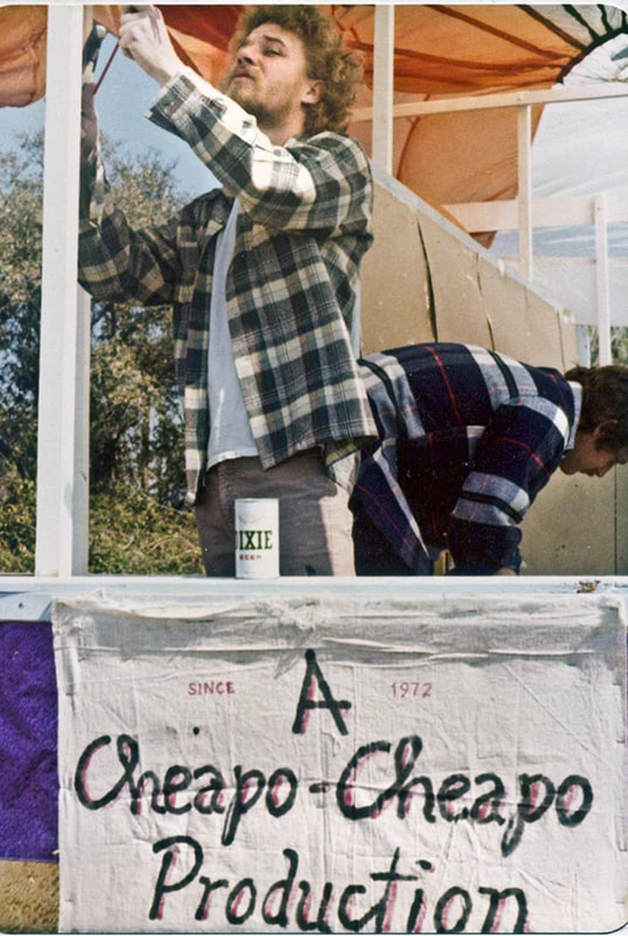

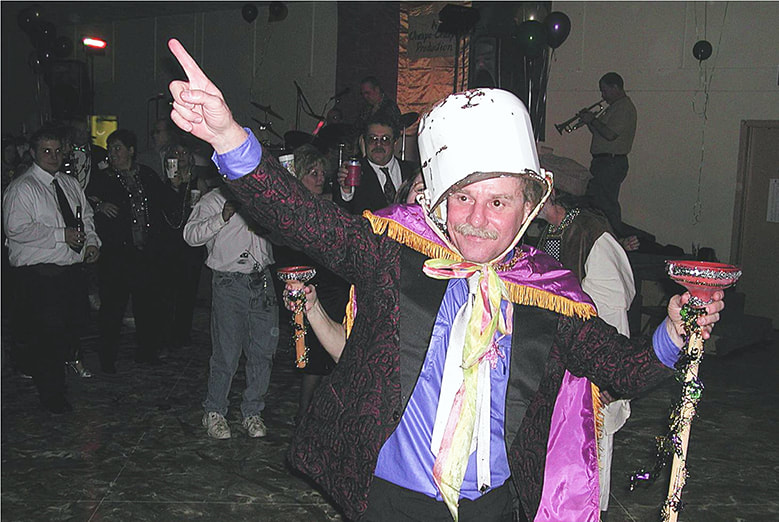

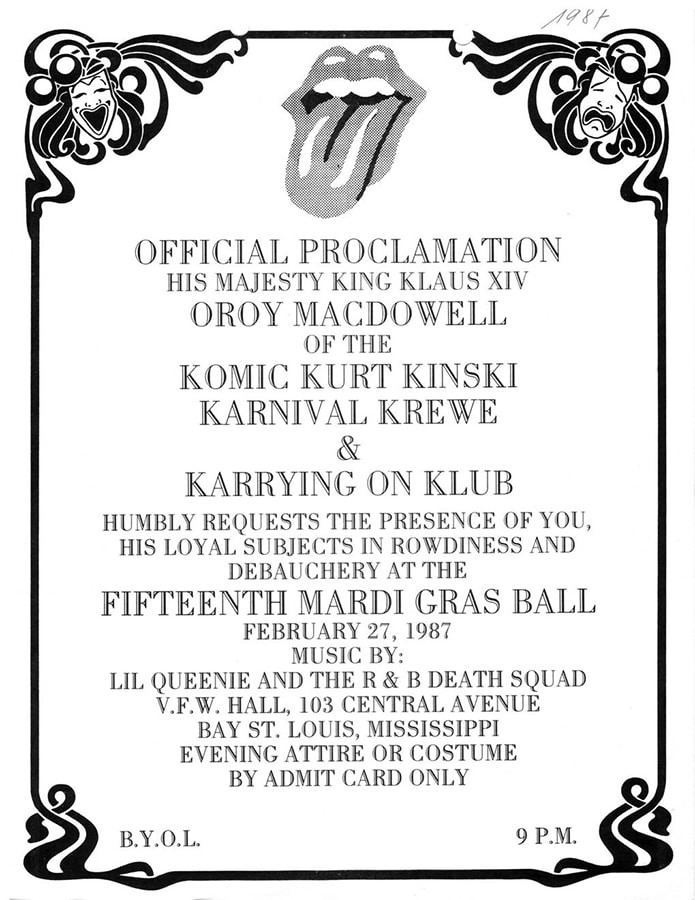

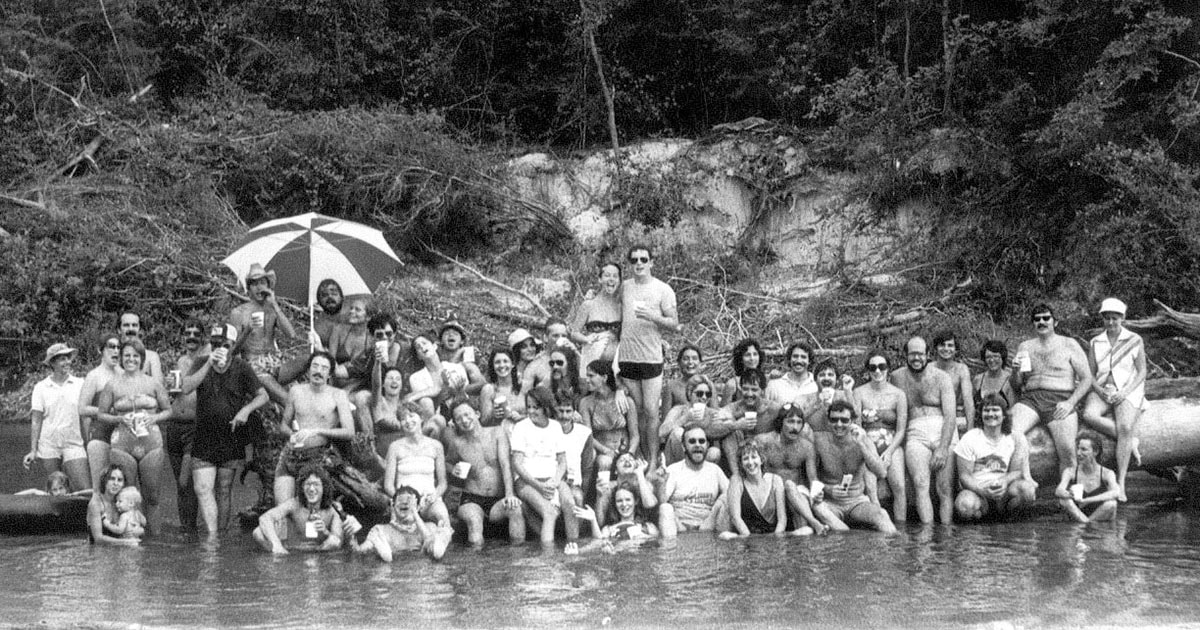

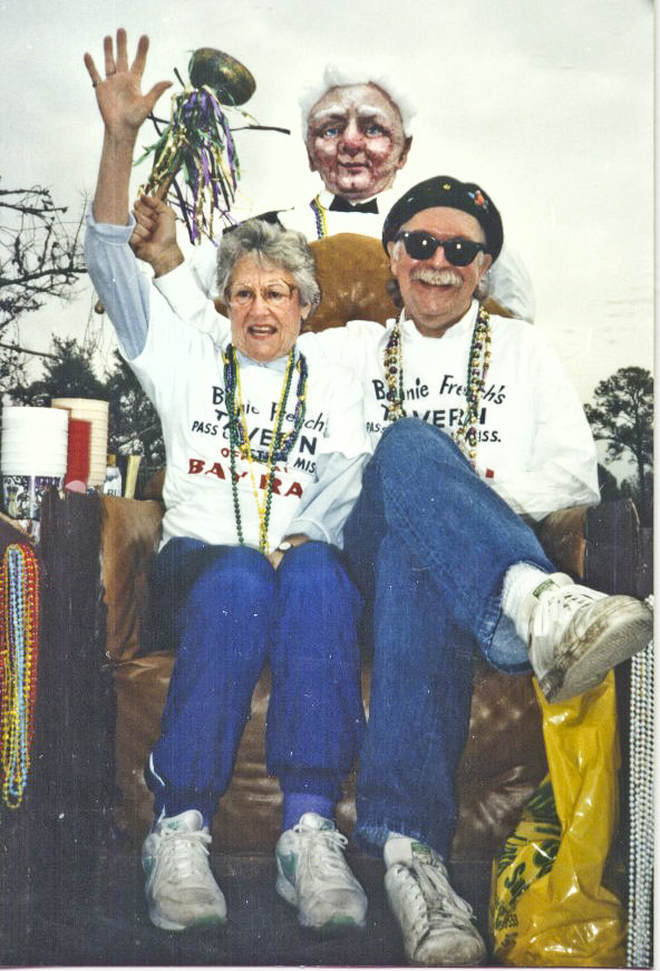

The official name of this rollicking group is the Komic Kurt Kinski Karnival Krewe & Karrying On Klub. Founding member and Bay historian Pat Murphy reveals the club's origins 46 years ago and hints at its future.

- by Pat Murphy, photos courtesy of the Kinski Krewe and Ellis Anderson

On the drive home from Gulfport that night the topic of staying close in the future resurfaced and talk of some type of social club began to swirl. Before arriving back in Bay St. Louis it had already been decided to christen the loosely conceived social organization with the name Kinski.

The idea centered around bringing old friends together at least once or twice per year for social events. While this group was never in need of an excuse to party, they felt that this organization would be a way to make sure it happened. The party, quite simply, had to go on. Over the next several months there were additional meetings held to come up with some operational rules for this loose-knit organization. These meetings were held mostly around parents’ dining room tables and included a few more friends interested in being involved as things progressed.

Eventually the original group was christened the "grandfathers" of Kinski. This group of "grandfathers" included Pat Murphy, Wayne Fillingame, Ronnie Genin, Michael P. Larroux, Michael Reeves, Lee J. Hayden, David Adams, Steve Benvenutti, Jimmy Wagner, Mac Hadden, John Heath and Rory MacDowell.

Shortly before the end of 1971, the opportunity arose to ride on a Mardi Gras float in the Pass Christian parade. David Adams' father, Howard already belonged to a group that was participating in this parade every year. Howard offered to sell the Kinski group a dilapidated old float that was laying around behind the florist's greenhouses. For the modest purchase price of $25 Kinski bought the old float from Howard and the Kinski krewe was rolling just like that. Well, not quite, because with Pat Murphy's father pulling the float in a pickup, the tongue of the float broke off in the middle of the 1972 parade and the ride had to be completed in the back of the pickup truck. However, a marvelous time was had by all and a decision was made that this parade was to be the annual event that the Krewe would be centered around. The following year Kinski held its first "Mardi Gras ball" on the Saturday night before the parade at John Heath's parents’ home (without their knowledge while they were out of town). After about two years the ball was moved to the Friday night before the Pass parade. The thinking was that this would give the members a full day and night to recuperate from the ball before riding in the Sunday parade. In a somewhat loose coronation ceremony, Pat Murphy was crowned King Klaus I. The reason for his choice will forever remain a secret within the confines of the Kinski organization and its archives. Each year a new King would be crowned when the court was announced. The King would be decided upon by the King Selection Committee made up of the previous three kings, whose duties also included naming a Queen, Dukes and Maids for the court. After the King's ride in the current year's parade, he would serve as Kaptain of the Krewe, overseeing the business of the organization until the following year. Prospective new members were only brought up for vote before the organization after they had been accepted and approved in a closed meeting of “grandfathers."

In 1979 Kinski began to have live entertainment for their Mardi Gras Ball. Through the years some stellar entertainment played for the Kinski Balls. Marcia Ball played three or four times as well as Anson Funderburgh & The Rockets, Lil' Queenie & The Percolators, A Train, Zachary Richard and John Mooney & Bluesiana to name but a few.

The Kinski balls were created as spoofs on the formal New Orleans Mardi Gras ball's pomp and circumstance. The King’s crown has always been dilapidated old porcelain chamber pot while his scepter was a glittered plumber's helper. Irreverence has always been the Kinski Krewe's central theme. When the organization was founded, no one thought that it would expand beyond a tight-knit circle of close friends. Through the years the circle eventually expanded to include friends of friends, younger brothers, cousins, etc. Members have come and gone. Some of the grandfathers have become inactive and no longer participate in the functions or business of the organization.

Through the years Kinski held other events in addition to the ones at Mardi Gras. Some, like The Basket of Cheer Raffles and The Spring Barbecue, were fundraisers for the group while Cat Island and Wolf River camping trips, crawfish boils and bonfires were simply social gatherings for members and guests

For a number of years the Kinski float was kept in a "den" that the group constructed on property owned by Howard Adams next to his greenhouses in Pass Christian. Later the float was moved to property belonging to the Battalora family's Pass Wholesale Supply. Both of these dens were destroyed in Hurricane Katrina and the float sustained substantial damage but was repaired and continued to roll. Eventually in 2010 the organization rode in the Pass parade for the final time and the float was brought to Waveland and a warehouse on property owned by the Markel family. Several years later in 2014, the group began to ride only in the Waveland St. Patrick's Day parade. Through the years, especially when members were a bit younger, there were some particularly spirited parade rides, especially in the Pass Mardi Gras Parade. The details of these spirited rides shall also remain within the confines of the Kinski Krewe archives. What went on back there stays back there!

Any of the original friends present at those dining room table planning sessions would tell you that it was never envisioned that the organization would continue as long as it has. Never in anyone's wildest dreams was it thought that this club would still be in existence 46 years later!

With the passage of time membership and annual participation has waned. Some of even the youngest in the group are now grandparents and many members, frankly, have other priorities today. There has been much speculation that the 2018 Waveland St. Patrick's Day Parade will have been be Kinski's Last Ride. If you attended this year's parade you saw lots of cabbage, carrots and corn being thrown from the Kinski float as well as the usual spirited irreverence toward everything! After the parade the Krewe threw a "Kinski's Last Ride" Part One celebration in the Longfellow Civic Center at the top of the Bay St. Louis parking garage. "The Garagemahal" as it is affectionately known to many, was a fitting location for the krewe party. Only a limited number of tickets were sold and the affair was a sellout. The Kinski Krewe's first king as well as twenty-first king, Pat Murphy and his band, 'Sippiana Soul played to a packed room full of dancing, partying people.

Many who had enjoyed Kinski's Mardi Gras balls and functions through the years were in attendance on the chance that the event would be sending The Komik Kurt Kinski Karnival Krewe & Karrying On Klub riding off into the sunset. Whether the event was or was not the krewe's last ride remains to be seen but regardless, what a ride it has been! Readers may want to stay tuned for possible Last Rides Part etc., etc.

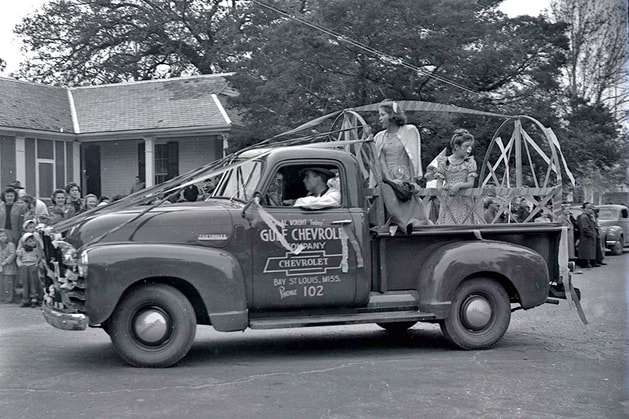

Lisa Monti takes a look back at Mardi Gras in the Bay, remembering parades, throws and the Krewe of Real People's legendary Moss Men.

- photos from the Scafidi collection at the Hancock County Historical Society and courtesy Edward Carver

Every community along the Coast fashioned its own Mardi Gras fun with balls, parades and royalty, going way back to the early 1900s in the case of Biloxi.

Mardi Gras in the Bay, Past & Present

As a kid growing up in Bay St. Louis, Mardi Gras day was the whole Carnival season. That was well before Carnival associations multiplied, their seasonal celebrations proliferated and King cakes were sold at drug stores and grocery stores. Costumes for the most part were homemade, as were Halloween costumes, sometimes becoming interchangable. Accessories were mostly rubber masks that covered the whole face or lipstick and rouge applied in excess. I can remember joining cousins of stairstep ages dressed as cowboys and Indians and gypsies, some wearing scary masks and all holding tight to our bags of throws.

We stood for what seemed like the whole day along a forgotten parade route (maybe on Necaise Avenue?) waiting for the horseback riders, police cars, marching bands and some form of humble floats.

For a time and for some unknown reason, wooden nickels were especially prized throws, though I can’t recall any redemption value. My most memorable throw came courtesy of a long forgotten bakery that provided miniature loaves of sliced bread tossed sparingly to the crowds. To a kid who was captivated by anything shrunk down to a perfect tiny replica, it was a magical possession. Someone recently asked if I remembered when Mardi Gras beads were made of glass before plastic became the favored material. Hard to imagine now that hazard waiting to happen, but so was running behind a mosquito-spraying truck and other experiences done in the name of 1950s fun. Another memorable component of Bay St. Louis Mardi Gras starting in the mid-150s was the marching Moss Men, which Bay resident Larry Lewis recalled in his Good Neighbor profile six years ago. What do Moss Men look like? “Something like a gorilla suit,” said Larry in his Shoofly interview.

I remember the Moss Men dancing in the streets but my most vivid recollection was the terror my very young niece Becky suffered when she first laid eyes on them. To this day, when we talk about anything related to Mardi Gras, the Moss Men always come up. And so do a lot of memories of large family gatherings on Mardi Gras day, homemade costumes, jumping and diving for trinkets and looking down the street for the next truck float or marching band to appear.

We never wanted the parade to end. All because it's Carnival Ti-i-ime Whoa, it's Carnival Time Oh well, it's Carnival Time And everybody's havin' fun Click here for the Shoofly Magazine's historical perspective on coast Mardi Gras celebrations. Click here to read about former Moss Man Larry Lewis in the Shoofly archives.

In the century since it'd been constructed, the building had served as a school, a community center and a place for healing broken lives. But no one had ever called it "home."

- by Ellis Anderson

Although shoofly decks were nearly extinct on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, three women decide that Bay St. Louis should be home to at least one: how the town's current shoofly came into being.

- story by Ellis Anderson

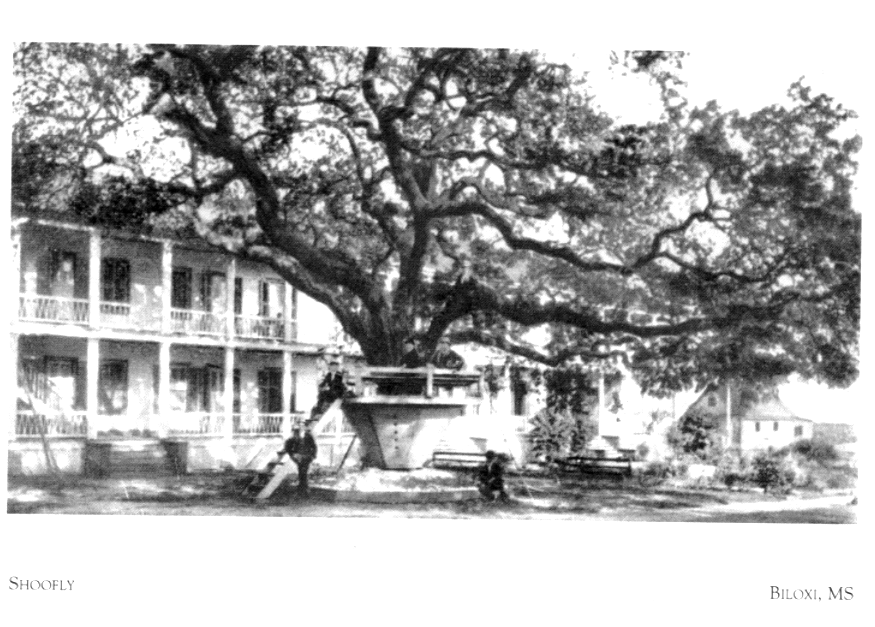

By the late 1900s, only a few remained on the entire coast. An iconic one stood in the Biloxi Green. Another had survived somewhere in Ocean Springs. Bay St. Louis had none.

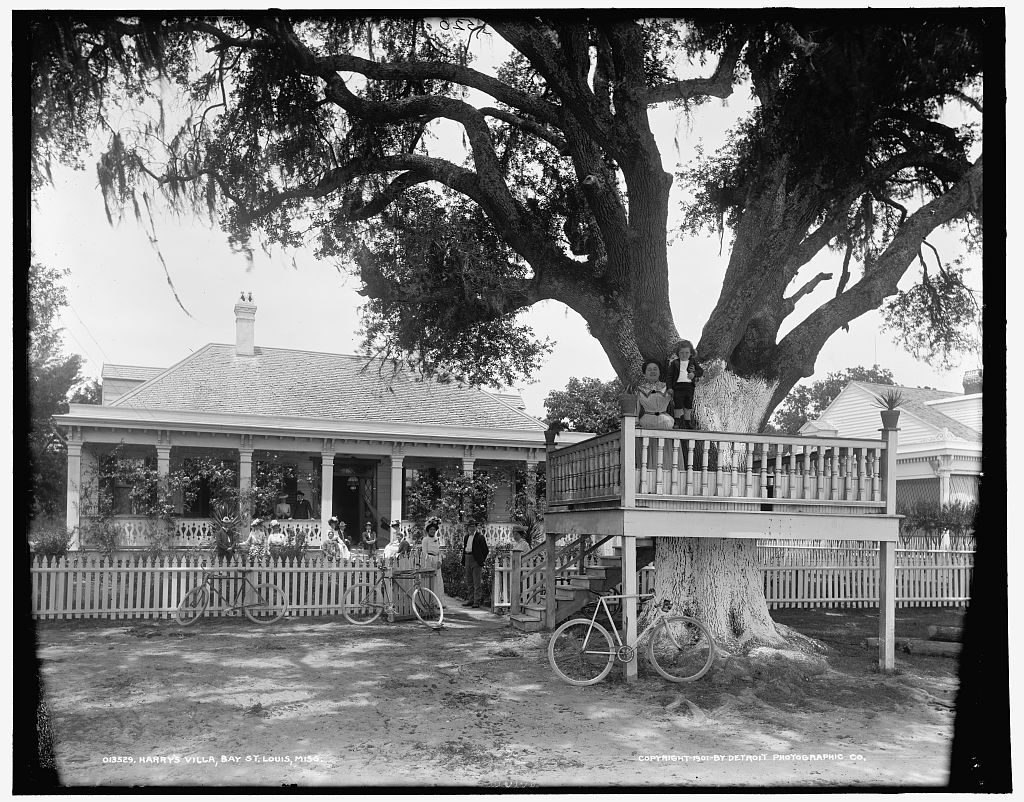

What had survived though are two astonishing photographic images preserved in the Library of Congress. Both were taken in the Bay around 1900 by a photographer named William Henry Jackson. Jackson took them for the Detroit Photographic Company, a national postcard enterprise. The images show different views of the same Beach Boulevard shoofly. Jackson took one picture from the road looking toward the house and called it “Harry’s Villa” after the first name of the owner. The shoofly is in the foreground, an elegant wood home behind it. A woman stands on the shoofly, while a boy is perched in the fork of the tree trunk, temporarily taller than the adult.

Jackson shot the other perspective from the porch of the house, pointing his camera toward the water. In the picket-fenced yard are Harry’s wife, Mrs. Boyle, their daughter and a grandchild. Several people stand on the deck of the shoofly. Judging by their hats and dress clothes, they’re probably guests at the Boyle’s boarding house.

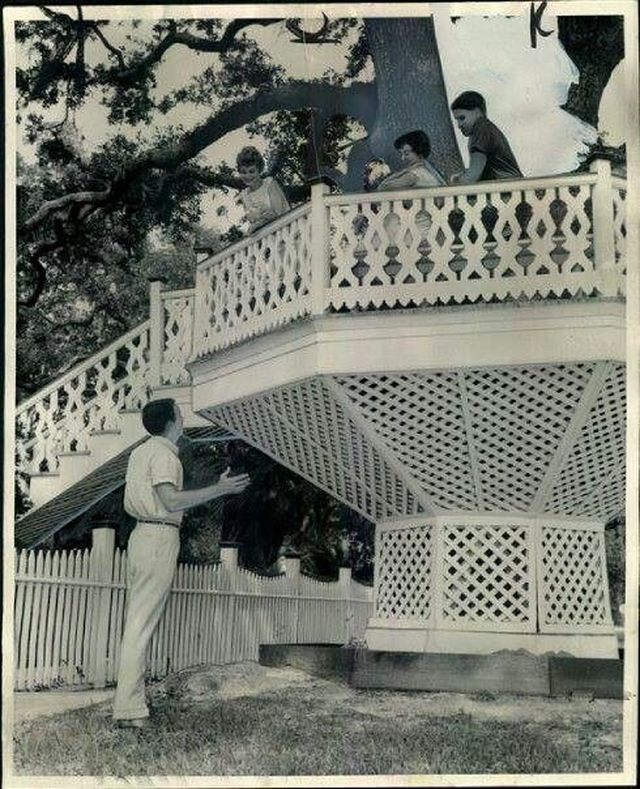

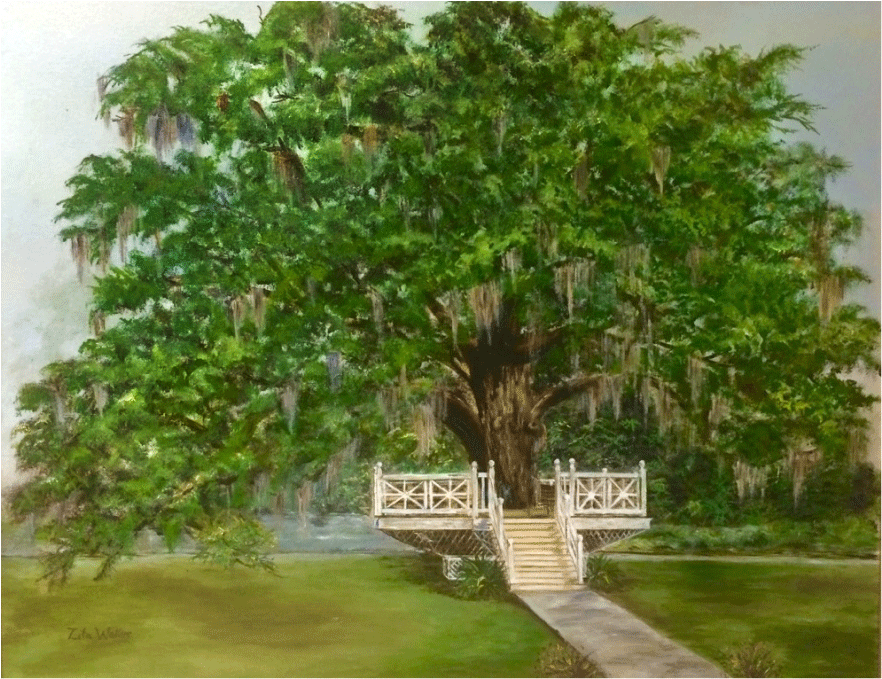

Yet, despite its historic shoofly stardom, Bay St. Louis remained shoofly-less until 1989 or ’90, when three Bay residents – Mike Cuevas, Zita Waller and Pat Cucullu – visited Ocean Springs for a home tour. Waller and Cucullu have passed away, and Cuevas tells the story. One of the featured houses – Cuevas doesn’t remember exactly where - had a shoofly in the yard. The three were enchanted and took photos.

Cuevas, who worked for the city, asked Mayor Eddie Favre, who was serving his first term, if building a city shoofly in the Bay was a possibility. “He said the same thing he always did when I asked him for something,” recalls Cuevas. “He said, ‘Sure, you raise the money and we can do it.’” The live oak on the property of the historic City Hall on Second Street was chosen to host the project. Cuevas says that later Farve himself found the funding to add to donations that came in. Architect Kevin Fitzpatrick and engineer Wayne Peterson volunteered their professional services, making the project a possibility. In the end, the cost for the shoofly construction was around $20,000, with the public works department providing the labor.

Fitzpatrick, an architect well-versed in historic preservation (he currently serves as chair on the city’s Historic Preservation Commission), remembers the project well. As a college student before Camille, he often traveled the coast, driving between Tulane University in New Orleans and his parents’ home in Florida.

“Back then, it seemed like the coast was covered with them (shooflies),” Fitzpatrick said. “I’d always admired them, so I was able to design the Bay’s pretty much from memory.” Fitzpatrick designed the railings to match the ones on the historic city hall, while engineer Wayne Peterson worked on the structural engineering. Fitzpatrick said he remembers joking with the engineer after seeing the support system Peterson devised. “I told him that we’d be able to park a locomotive on that thing,” Fitzpatrick said. “It seemed way over the top. But Wayne believed that people would assemble on the Shoofly for weddings and events, so it had to be extremely strong. And he was right.” Peterson’s other concern was for the tree itself. The deck had to be self-supporting so it wouldn’t harm the ancient oak and it had to allow plenty of room for the tree to grow. According to Peterson, “The base at the ground is close to the base of the tree, with the platform cantilevering out at the top. In addition, the structure had to be designed to support a lot of ‘weighty politicians.’ I understand that it has successfully supported a lot of those over the years.” “It’s still something when I see it,” says Peterson. “My hope is that it gives people a little of the pleasure that growing up and living on the coast has given to me.”

Of course, the Shoofly Magazine is named after the iconic town landmark - a perfect place for elevated community conversation!

Common Ground

A small shrine to Our Lady of the Woods has become a touchstone for two girls' schools - together spanning more than a century and a half.

- story by Ellis Anderson

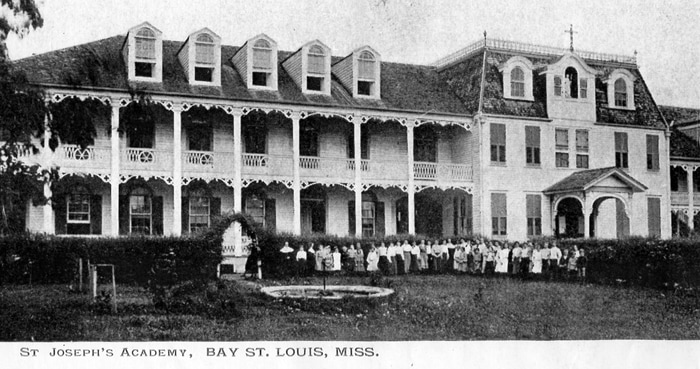

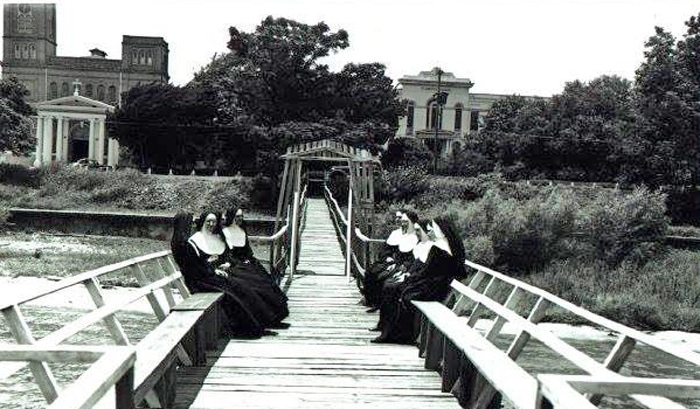

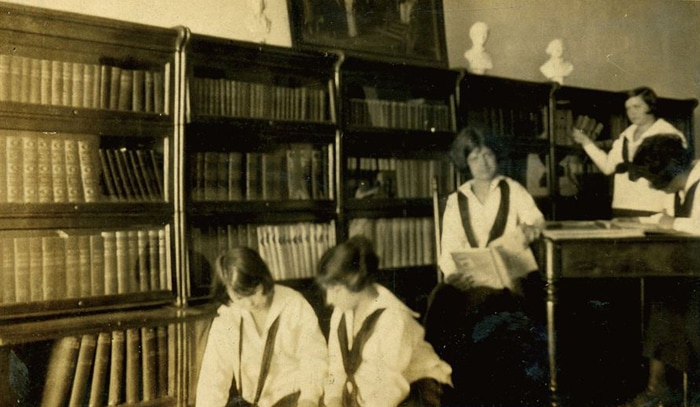

The grotto was built in the 1860s on the grounds of St. Joseph’s Academy, a parochial girls’ school that was just a few years old at the time. St. Joseph’s was started by three hardy French nuns who made the journey across the Atlantic for just that purpose. Classes filled immediately.

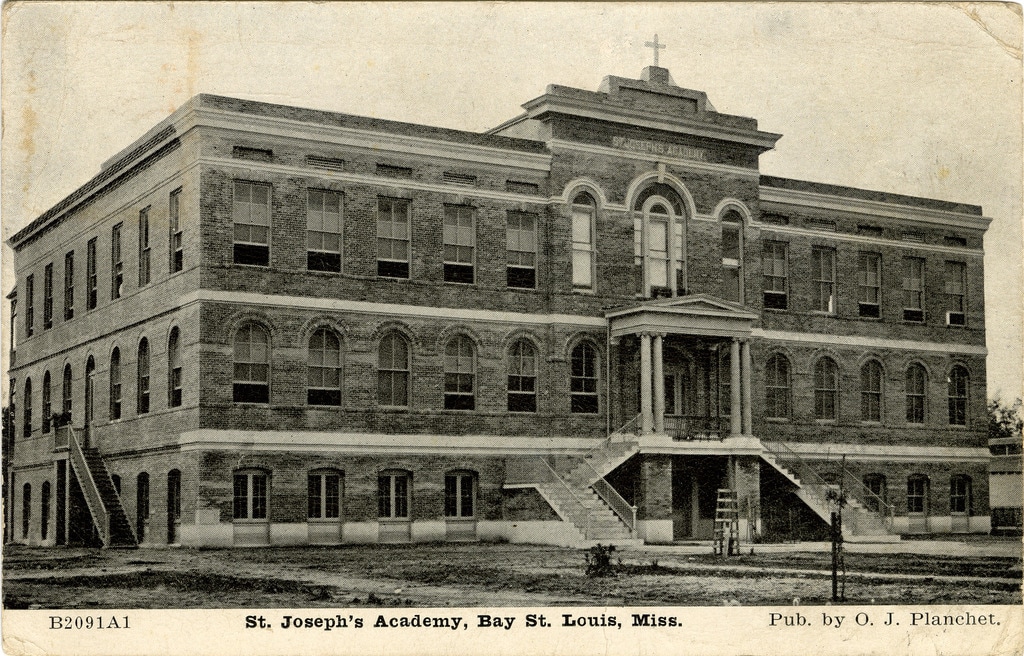

According to an excellent article on the Hancock County Historical Society’s website, the presence of the nuns heartened Father Buteux, the pastor of Our Lady of the Gulf Catholic Church. He wrote about their arrival with great enthusiasm in his 1855 diary. Bay St. Louis then was a primitive village. Living conditions would have been Spartan, even by standards of the day, without conveniences like electricity or running water. Yellow fever and other diseases were always a threat. Yet three more nuns arrived the following year. By the 1860s, when the shrine was built, the school began to offer boarding facilities. Board, tuition and washing (of clothes, presumably, not students), cost parents $220 annually in 1867. The grotto was built after a perilous trip Father Buteux made, sailing from France back to the States. Caught in a violent storm that sheered the mast from the schooner, the priest promised to build a memorial to the Blessed Mother if she would spare the ship and its passengers. In those early days of the city, the shrine was set deep in the surrounding woods. St. Joseph’s Academy continued to grow through the years, gaining a national reputation for scholastic excellence. Unfortunately, an enormous fire ravaged much of the town and destroyed the school and the church in 1907.

The plucky nuns rallied with wholesale community support and found funding to build a new school. They and their students moved into an elegant new three-story building in 1908. In 1924 a companion two-story brick building was constructed. Referred to as the gymnasium, it was used for music and other classes as well.

The ultimate demise of St. Joseph’s came from a scarcity of teaching nuns rather than a diminishing student body. The front building that had been built in 1907 was torn down after the school was closed in 1967. According to one graduate, it was an act that came as a shock to the town’s residents and the alumni who cherished the architectural treasure. The gymnasium was destroyed by another fire a few years later. Hurricane Camille in 1969 scoured the grounds. The Our Lady of the Woods shrine was all that remained. A campus that had been one of the prides of the coast no longer existed. And local parents who wanted a parochial education for their daughters had to look elsewhere.

Then, in the aftermath of Camille, a local attorney with four daughters kick-started a drive to establish a new girls’ school at the site of the former. The late Michael D. Haas teamed with the pastor of OLG, the late Msgr. Gregory J. Johnson and Brother Lee Barker, who was principal of St. Stanislaus College prep school at the time.

Haas’s wife, Myrt, calls herself the original naysayer of the project. When the idea was first discussed, she found it difficult to believe such a grand dream could be brought to fruition. But her enthusiasm quickly caught fire. She remembers that the concept had instant “wholesale community support.” Many obstacles had to be surmounted. For instance, the group discovered the new school couldn’t receive accreditation without a science lab, a library, or language courses – things that seemed out of reach with their limited funds. But Father Lee offered to share the facilities at St. Stanislaus, an unprecedented move. Co-educational programming between the all-boys school and the female students at St. Joseph’s had never before been considered. “Our girls learned a lot from the experience,” says Myrt, laughing. “For one, they learned to put on lipstick before they went over to the St. Stanislaus campus.” Myrt says that the main reason the school succeeded was the good attitude of the early students. In those early days, they didn’t have the resources that the public schools did. For example, there was no cafeteria, considered a school basic. “I give the students credit for sticking with it and making it work,” Myrt says. “Those girls made it happen as much as the parents and teachers.”

Current OLA principal Darnell Cuevas, who’s been at the school’s helm for two years, says that the school’s enrollment is nearly up to pre-Katrina levels now, with more than 250 students. The students are excelling academically as well. In 2017, 38 graduates scored in the top tier on standardized college entrance tests and were awarded nearly $5 million in scholarships.

The Our Lady of the Woods grotto has become a historical and spiritual tie between the two academies. It’s a favorite place for group photographs of students, teachers and St. Joseph’s graduates, who reunite often. In May of this year, more than 40 students and teachers from the final class of 1967 gathered for their 50th reunion. The grotto was a favorite meditative spot for Cuevas, even before she began as principal, and she’s eager to see that her younger charges learn the history of the shrine. Both Myrt and Cuevas speak fondly of the legendary caretaker of the shrine, Sister Albertine, who kept the grotto tidy and with a candle burning at its base around the clock, throughout the year, for decades. Myrt tells the tale of wartime sacrifice that kept Sister Albertine from performing her duties. “During World War II, enemy submarines were patrolling the waters of the gulf,” says Myrt. “We had blackouts every night. Lights had to be turned off in houses and buildings. Even cars couldn’t drive the coast roads with headlights.” “The Coast Guard came to St. Joseph’s, saying that they could see the candle at the foot of the shrine more three miles out in the gulf. Sister Albertine had to stop lighting the candle. But just for the time being.” 1985: A Church Fair Becomes Crab Fest

"Crab Lady" Pam Metzler and other Crab Fest veterans share the history and traditions of this favorite coast festival.

- story by Lisa Monti and Tricia Donham McAlvain, photographs by Ellis Anderson

“We don’t charge for admission so it’s impossible to know how many people come in, but it’s thousands. At night sometimes you can hardly walk,” said longtime Crab Fest chairperson Pam Metzler.

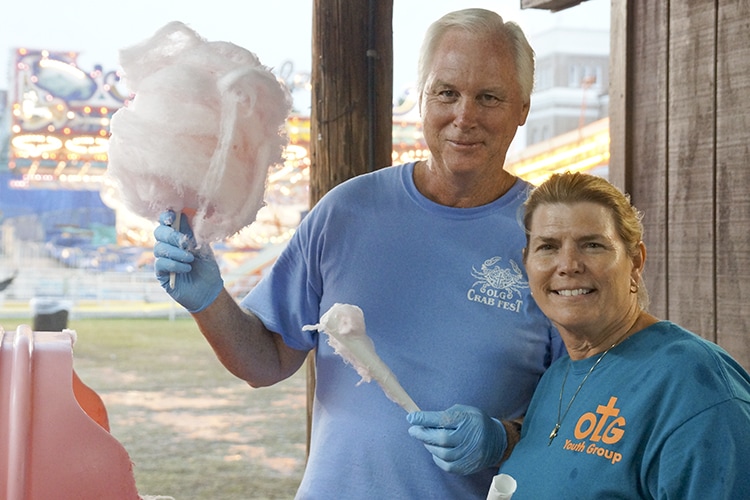

Church fairs were a big part of growing up here, and many volunteers are carrying on a family tradition. “All the local church families worked the fair,” said Metzler. “My mom worked the cake booth.” The first few years of the festival, it was held on property that celebrity clarinetist, Pete Fountain owned (near the foot of the bridge where the Chapel Hill neighborhood is now). Pat Murphy remembers playing there with his wife Candy, guitarist John Bezou and drummer Jerry L’Enfant. Metzler says the festival was moved to the church/school grounds because the shade from the live oaks gave some relief from the mid-summer heat, yet still allowed for breezes from the gulf. This year’s Crab Fest will be the 20th year Metzler has served as chairperson. In 1997, Pam, who was Hancock County's circuit clerk at the time, was approached by Father Pete Mocker, who asked if she'd take on the enormous job of chairing the event. After consulting with her family, who promised to help, she took on the job, becoming the first woman to do so. Now she's retired from the county, but not the Crab Fest. She and the other dedicated volunteers return year after year to keep the pieces and parts of this three day festival rocking along. It’s hard work, in the heat, but they enjoy it. “Everybody always has a wonderful time. A lot of volunteers aren’t even church members, they’re just members of the community or members of other churches, other denominations,” Metzler said. “Because it’s so fun.”

Just a few of the regular volunteers

(editor's note: these Shoofly Magazine photographs were taken before 2017 and a few of the folks below have passed away since then).

Metzler and others shift into Crab Fest mode in January, and a few even set up camp on the fair grounds ahead of the opening. “Six months ahead of time, they start getting ready to prepare food,” Metzler said.

Laura Piazza Griffith (editor's update: Laura passed away in 2019) makes 600 pounds of crab stuffed potatoes. Others boil 7,000 crabs and 3,500 pounds of shrimp. Some fry the seafood and make the gumbo and other items. Kevin Haas and Mike Gibbens have been boiling the crabs and shrimp since the beginning days of the festival. "Starting 15 years ago, we got it down to a science,” said Haas. “We boil the crabs and shrimp separately in big pots with baskets in water. Then we cool the crabs or shrimp in water with seasoning, in what we call "charge pots" and then they are ready to eat.” The Monti family has been involved in the Crab Fest since before day one. “The Monti brothers, Bill and Joe, had the original idea for the Fourth of July fair and carnival,” said Metzler. “They said let’s do a crab festival, it’s the Gulf Coast and there was no one doing one at the time.” The late Gene Monti (“The Sweetest Man in Town”), his wife Mary Alice and his sister Lydia Favre were long time volunteers. Gene was well known as the cotton candy man and he also handmade cast nets that were raffled off. The husband of Monti’s niece carries on the traditional of knitting crab nets that are raffled. “It’s a great, great festival and so much fun. We laugh and we work and we’re tired, I truly love it,” Metzler said. “I tell people you can’t quit the Crab Fest, you have to die to get out,” Metzler jokes. “We’ll be 80 and still be out there boiling crabs.” And for those who make it to closing, there’s even a fun tradition. “We get the band to play the second line and the die-hard volunteers who have stayed to the end dance all around the pavilion waving napkins," says Metzler. "When we throw our napkins down that means Crab Fest is officially over for the year." "Then, we go soak our feet in the [soft drink] cooler with the leftover ice," she says, laughing. The Legendary (and Non-existent) Captain Longbeard

Pirate Day is the Bay is centered around a pirate named Captain Longbeard, but it turns out that he's a shipmate of the fictional Jack Sparrow.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

The Krewe has created a mock-history based on the real deal, a story that’s much more colorful that the rather dry history and features a fictional character called Captain Longbeard (each year played by the current king of the Krewe).

Captain Longbeard is now taking on legendary status. John Rosetti, 2017 president of the KOTMS, says he found it hilarious last year when one television station talked about Longbeard as if he were a real historical figure. “He was just something I drew up on a napkin,” says Rosetti, laughing as he recalls how the character was created. The actual historical event at the center of all this merriment happened in 1814 as a precursor to the more famous “Battle of New Orleans.” The Sea Horse was an American schooner that single-handedly took on the British fleet in a “David versus Goliath” encounter, right in front of the Bay St. Louis shoreline. While the little ship was hopelessly out-manned, it managed to delay British forces, giving Andrew Jackson (who was commanding American forces in New Orleans) more desperately needed time to organize that city’s defense and keep control of the Mississippi River out of British hands. Since the event occurred two centuries ago, accounts of the battle vary, but as local historian Charles Gray often says, “history is lies agreed upon.” The most riveting part of Gray’s version occurred when an older woman on crutches shouted to shore-side onlookers of the battle “Will no one fire a shot in the defense of our country?” She then grabbed a lit cigar being smoked by Bay St. Louis Mayor Toulme and lighted the fuse to a cannon, which fired into the midst of the British attackers. Mayhem ensued.

The battle’s connection to pirates is very tenuous, but the Battle of the Bay did take place in 1814 when buccaneer types abounded in the area. In fact, legend has it that the real legendary pirate, Jean Lafitte, had a house on the beach near the BSL/Waveland line.

And historians do agree that a few weeks after the Bay St. Louis battle, Lafitte and his band of ruffians fought alongside Andrew Jackson in New Orleans to repel the British invaders – a battle that probably would have been lost without the pirates’ help. But don’t let the facts stop the fun. Captain Longbeard – this year played by MKOTS king Al Copeland – will be storming the town on the weekend of May 19th and 20th. If you’d like to read more, details of the actual battle can be found here on the Krewe of Seahorse’s website. Also, Charles Gray suggests reading Paul La Violette’s 2003 book, Sink or Be Sunk! The Naval Battle in the Mississippi Sound That Preceded the Battle of New Orleans. It’s available at Bay Books on Main Street. Historic Tour of Old Town

Wend your way through Old Town taking in the Bay's historic gems with the paper - or the mobile - version of this popular tour.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson

The original wooden Depot was built in 1876, and was destroyed by fire approximately 50 years later. The present structure was built in 1929, in Spanish Mission style. A park surrounds the Depot and includes a walking track, a duck pond and picnic tables, all under shade provided by large live oaks. The fanciful building served as a set for the 1965 movie, “This Property is Condemned,” starring Natalie Wood and Robert Redford, directed by Sydney Pollack. It was one of Redford’s first films.

Just a block away, at 398 Blaize Avenue, stands the real star of the movie, the “Starr Boarding House.” Most of the film centered around this building, but its star status didn’t prevent it from languishing for years and nearly being demolished. Saved in a dramatic last-minute community effort, the building was meticulously restored with the help of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History post-Katrina. It now serves as home to the Bay St. Louis Little Theatre.

Some other personal favorites on the tour:

Tercentenary Park, which memorializes Bienville’s entrance into the Bay of St. Louis over 300 years ago. The park is located on the point of highest elevation on the Gulf of Mexico - 31 feet. It’s the official starting point of the tour, but one can begin anywhere and enjoy the stroll. The Palm House, close to the Depot (217 Union Street), is a West Indies Planter style house built in the 1880s. For many years, it was the home of Joan Seal, the wife of a circuit judge. Mrs. Seal was recognized as a generous philanthropist in this area and so devoted to her dogs that she left provisions for them in her will.

The Piernas House, at the corner of South Toulme and St. John Street, is a side gallery cottage, and former home Louis Piernas, a free black man who was a community leader. In 1889, he received a presidential appointment to serve as postmaster of Bay St. Louis. Piernas, who lived to be 98, also served as chairman of the Hancock County Republican Party for 65 years, even traveling to Chicago for the 1882 convention.

The Weinburg House and Cobbler’s Cottage - 112 South Second Street - was originally constructed by John Himes in 1868. Based on its hip or gable-on-hip roof and undercut gallery, the larger house is identified as a “Biloxi Cottage.” It’s now home to the popular Mockingbird Café. Next door, the eye-catching – and very diminutive – cottage served as the workshop of cobbler Manuel Maurigi for many years. One can imagine the delight of his ghost at seeing the cottage now, filled with artwork as the home of Smith & Lens Gallery.

The Railroad Street Houses are located at 125-129 Railroad Street. These Queen Anne Revival style homes were built by Eugene Ray, an African-American who was a respected local contractor and undertaker. The largest of the three houses was home to the beloved bishop who was born in Bay St. Louis, Leo Fahey.

100 Men Hall, located at 303 Union Street, isn’t on the tour’s official route, but is suggested as an “Off the Beaten Trail” destination. The blue and white clapboard building was built in 1922, and was such an important and popular site for music - and socializing - that it is included on the official Mississippi Blues Trail.

St. Rose de Lima Catholic Church (301 South Necaise Avenue) is a short hike from the 100 Men Hall and is also highlighted by the tour. The church was built in the mid-1920s, by local craftsman Joseph Labat. The “Christ in the Oak” mural behind the altar is a nationally recognized work of art.

The Old Town Biking/Walking Tour was conceptualized, written and photographed in 2008 by Ellis Anderson. Historian Charles Gray contributed stories of local lore (especially the more colorful bits) and helped with research, while graphic designer Jenny Bell of Adlib designed the brochure. Live Oak Alliance, a non-profit headed by Marcie Baria, backed the project and brought the tour to first fruition.

The first printings were completed with the help of a grant from the Mississippi Gulf Coast National Heritage Area and funding from Live Oak and other local sponsors. Currently, printings are coordinated by the Hancock County Tourism Development Bureau and are sponsored by the Bureau, the Hancock County Historical Society and Ellis Anderson Media. Myrna Greene, executive director of the Bureau, calls the tour brochure “the most effective and popular tool we have to introduce people to Bay St. Louis.” It’s updated periodically and is scheduled for a fourth reprinting in March 2017. Perhaps the most memorable part of the tour however, is the people you’ll meet along the way. When you’re taking the tour, expect the warm and friendly nature of the neighbors along the way to make the experience even more memorable. I even had someone ask me for directions to the Hancock County Historical Society. I gave them the guide. You wouldn’t want to miss Kate Lobrano’s house on Cue Street!

Note: Since several of the buildings on the tour route are private residences, the tour brochure specifies on the opening page: “While we encourage exploring our public treasures here, please respect the privacy of our residential listings.”

A Legacy of Joy

The Krewe of Nereids celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2017 and membership for some has become a treasured family tradition.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson, Ana Balka and courtesy of Nereids

The krewe has 134 members; 101 are casting members who participate in the ball and parade. Of the 134 members, the krewe has 50 members who are legacy members. The genealogy of families with generations of membership is complicated, but altogether fun.

Several legacy members said that while it is an honor to be named queen, it's even better is to see one’s own children, grandchildren, sisters, and nieces join and participate in the traditions of the Krewe of Nereids. One example of family heritage in Nereids is the Ladner/Turcotte/Roche family, represented by 19 members. Four generations have served in a variety of roles at the annual ball including pages, maids, and queens. One member explained, “Most of the children are involved as they are growing up. Whether it is dancing in the balls, helping their moms with beads, floats, whatever is needed. So becoming a member is just the next natural step.”

In some social organizations, legacies (aka female family members) are given preference for membership. The Krewe of Nereids’ approach is different: applicants with family members in the krewe are reviewed for membership without favoritism.

A requirement for membership is for the woman to be 21 years old or older. Despite the age limit for membership, young people (children and grandchildren) can serve as pages. The Krewe of Nereids is a multicultural, multi-faith organization. It's not a secret how to become a member of the Krewe of Nereids. First, you complete an application, which you can get from a member of the krewe or from the website and have three members verify that you would be a good member. The krewe board will meet to approve or disapprove the request and vote whether to accept or not. Heritage is not limited to the women and girls of this all-female krewe. According to many members, “We could not do it all without the men.” Husbands, sons, cousins, and grandsons participate by preparing floats, participating in the parades, and attending the lavish balls. They also serve as pages, dukes, and kings for the ball and parade. The king is selected by the captain. Several members spoke of the exhilarating nature of parading: waving at the crowd, throwing beads, singing to the music and, altogether, enjoying the experience! “The parade is exciting," said one Nereid. "[I would] never miss the parade. I would have to be dying!”

Past Nereids parades, photos by Ana Balka and Ellis Anderson

Each year during the parade, float riders throw signature beads, cups, and doubloons. Other throws include cups, posters, doubloons, and koosies related to the theme of the year. Stuffed animals and toys are also tossed out to a delighted crowd. Since 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the Krewe of Nereids, members are working on a special throw to celebrate that milestone.

February is the apex of activities for the Krewe of Nereids: the 50th annual ball will be held on Saturday, February 4, and the krewe will parade on Sunday, February 19 at noon. For additional information on the parade route or to purchase tickets to the ball, the tableau, or after-party, go to the Krewe of Nereids website. With the hard work of the krewe members and their families, both the 50th anniversary parade and ball will be magic! Bonfires on the Beach

One of the best loved traditions on the Mississippi coast - a bonfire on the beach to welcome in the new year.

- story by Rebecca Orfila

As the party reached the midnight hour, Clay draped his dress coat over Lucy’s shoulder and led her outside to his family’s bonfire. With the fire blazing and sparks flying in the wind, Clay kneeled and asked the young woman in the navy dress to be his wife in the new year. The year was 1927. The bonfire proposal apparently made a good impression: Clay and Lucy were married for forty years.

In this country today, many traditions celebrate the new year. The ball falls at Times Square, resolutions are made, kisses are shared, fireworks burst in bright colors in the sky. On the Mississippi coastline, the bonfires still burn brightly. People have lit bonfires in celebration or for sacred events for as long as we have used fire: funeral pyres, sacred rites, and even attempts to stave off plague have all led humans to light big fires. Louisiana’s River Road and bayous to guide Papa Noel have bonfires on Christmas Eve, the Epiphany, July 4, Mardi Gras, Good Friday, and New Year’s Eve. Here on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, we often light fires to celebrate those important holidays and other special days. Bay St. Louis is no exception; a January 1, 2006 MSNBC feature showed a bonfire on the beach across the street from Buccaneer State Park. It had been created by tired relief workers. Dozens of the volunteers celebrated the New Year with songs and prayers for a smoother 2006. They came back the next day to clear the burned remains of the fire and return to clearing more of the rubble left by Hurricane Katrina. The beaches in Hancock County now host more bonfires than ever before. In 2015, Waveland joined Bay St. Louis in allowing bonfires on beaches within city limits. Both cities require permits and deposits (see details below). And since fireworks are legal most years (they're sometimes locally banned because of drought conditions), the bonfires become a hub for families celebrating the incoming year with a little razzle-dazzle. Too much trouble? In Harrison County, there's even a new service that will build one for you, and even clean up afterward. But if you're not invited to a bonfire gathering on New Year's Eve and you're not up to building your own, don't mope. This is one coast tradition that's easily appreciated, even from a distance. As midnight approaches, take a walk along the beachfront for a memorable - and brightly burning - welcome to another year.

You'll find complete information about city regulations re. bonfires at the following links: The Bay St. Louis bonfire regulations and the Waveland bonfire ordinance.

Mississippi Heritage Trust

With Lolly Barnes at the helm, this organization is making enormous strides in the state, helping save our historic buildings for future generations.

- by Rebecca Orfila, photos courtesy MHT and Ellis Anderson

As in the case of Mary Helen Schaeffer’s home, MHT calls on volunteer professionals and other resources to help secure historical properties under threat of loss. In coordination with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, plus a number of state and federal funding agencies and available private and public funds, MHT strives to serve the state of Mississippi.

History and preservation are important to the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Many of the Coast’s historical landmarks and structures have been pounded by hurricanes and gales, resulting in historical homes left twisted and pushed off their foundations. Some damaged structures were abandoned. Lolly Barnes serves as Executive Director of MHT, which is supported by the MHT Board of Directors led by Doyce Deas of Tupelo. Along with Director of Programs Amber Lombardo and Special Projects Coordinator Erica Speed, Barnes is an active leader and contributor to the identification and preservation of historical properties and at-risk structures. Her team also develops educational materials and holds workshops throughout the state for preservationists, architectural historians, and historians. In recognition of her work with the Mississippi Heritage Trust, Lolly was recently awarded the Presidential Citation from John Beard, President of the Mississippi Chapter of American Institute of Architects (AIA). The award is given at the discretion of the AIA-MS President for exceptional work performed on behalf of AIA-MS.

The Mississippi Heritage Trust was established in 1992 as a non-profit organization. Its mission to save and renew places meaningful to Mississippians is accomplished by education, advocacy, and preservation. In a recent interview, Barnes said, “Informing the public of historical properties and their contribution for defining the sense of community” is an important component of MHT’s longstanding missions.

One of MHT’s biennial activities is the naming of the Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites in Mississippi. Barnes said, “The goal of the program is to raise awareness about the many threats facing our rich architectural heritage.” The first site identified on the Save My Place Program was the Biloxi Lighthouse, which was damaged by Katrina’s storm surge and high winds. It took over a year and $400K $400,000 to restore the structural and electrical components, plus the lookout windows. The restoration of the tower was complete and ready for tours in March of 2010.

In 2015, the 1929 Jourdan River School (formerly the Kiln Colored School) was added to the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites. The Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites is a program that serves to identify and champion the protection and restoration of important historical sites.

Other schools on the MHT list of recognition and preservation projects include the Randolph School in Pass Christian, West Pascagoula’s Colored School, 33rd Avenue School in Gulfport, and the old Pascagoula High School.

Also on the list is the Valena C. Jones Colored School in Bay St. Louis which is situated on a high point in town and received little damage during Hurricane Katrina. The Hancock County Emergency Operations adopted the structure as a base of activity. With input from MHT, the restoration of the gymnasium included new windows, reinforcement of masonry walls, and replacement of the classic curved roof of the gymnasium. Later, a Boys and Girls Club was established in the gymnasium.

The Heritage Award of Excellence for Restoration/Rehabilitation has recognized the Hancock Bank Building (Pass Christian), 513 E. Scenic Drive (Pass Christian), Beauvoir (Biloxi), Bay St. Louis City Hall, Dantzler-Fabacher-Franke House (Gulfport), and 139 Seal Avenue (Biloxi), and 123 Seal Avenue (Pass Christian), to name a few.

When asked what 2017 might bring for MHT, Barnes responded, “We will celebrate the 25th anniversary of MHT and another year of being a successful non-profit organization.” Important to the continuing life of the Trust, efforts will be made to “build out our capabilities as an organization” and to continue fundraising efforts.

On Saturday, November 19, MHT will present “Delta Drive-In” at the Burrus House in Benoit, Miss. The event celebrates the 60th anniversary of the filming of the cult classic “Baby Doll." There will be an open house to explore the exemplary restoration of the antebellum Burras House from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., followed by a screening of the film. Tickets are $75 a person, with proceeds benefiting the Burrus Foundation and the Mississippi Heritage Trust. See the Facebook event page for more details. Are you interested in attending the Delta Drive-in event or becoming a member of the Mississippi Heritage Trust? Contact MHT by email at [email protected] or phone at (601) 354-0200. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed