|

Arts Alive! Oct/Nov 2017

Creating portraits by embroidering can take up to a year to complete a single piece, but as she works, Ruth Miller is redefining tapestry - one thread at a time.

- story by LB Kovac, photos courtesy Ruth Miller

But they aren’t stately. By choosing domestic scenes and incorporating elements of African art, Miller is redefining tapestry, one thread at a time.

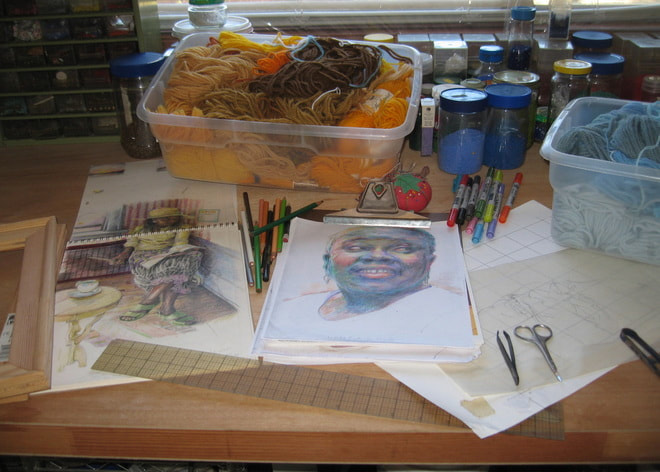

Ruth Miller herself is an unexpectedly quiet woman. On the phone, she has a sweet voice. She’s easy to talk to and laughs a lot. I imagine her smiling all the time. At home in her studio she says, when she’s working on a piece, she listens to audio books. “I need my mind to wander in two different directions when I’m working,” she says. “But it’s like driving—you get to a point where you don’t remember that you’re going somewhere, and then you’re there.”

But Miller didn’t learn embroidery there. She learned it where most girls of her era did: at home, from her female relatives, especially her mother and her aunt. “It was the end of those times where kids were universally taught sewing and embroidery.”

She recalls riding the subway to school and someone crocheting in a seat next to her. It would be an odd scene today, with ready-made textiles being so readily available, and so few people attempting such time-consuming art forms.

Miller says that she was inspired to think of embroidery as an art form by a Senegalese weaver. He produced tapestries that included abstracted and figurative art.

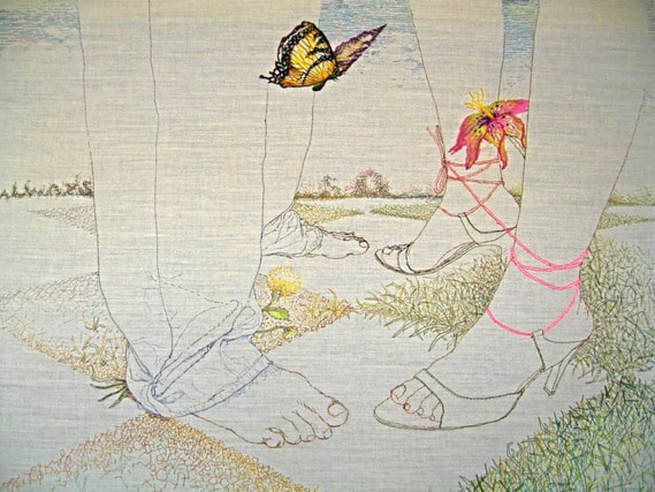

“I didn’t warm to paint at school, but I liked the cleanliness of textile art.” This weaver had a big impact on how she saw her own art. “He influenced my early attempts at style.” This is evident in pieces like “The Evocation and Capture of Aphrodite,” where a pattern that starts in background drapes before covering the back of the young girl’s shirt, or “Our Lady of Unassailable Well-being,” in which a smiling woman’s face is framed by a colorful pattern. For much of her life, Miller lived in the northern states, but she recently moved to Mississippi for two reasons: “I was looking for a place and time to make art,” and “I was looking forward to getting to know my family.” Miller’s mother was born in Meridian, and she herself had lived here once in the 1970s, before going back to New York. In a studio in an unincorporated area of Hancock County, Miller makes her art. The change of pace from fast, breath-taking New York to easy-going rural Mississippi no-doubt contributes to her art.

Miller’s works do have one major thing in common with Romanesque tapestries: time. Art historians estimate that the Bayeux Tapestry took ten years to produce.

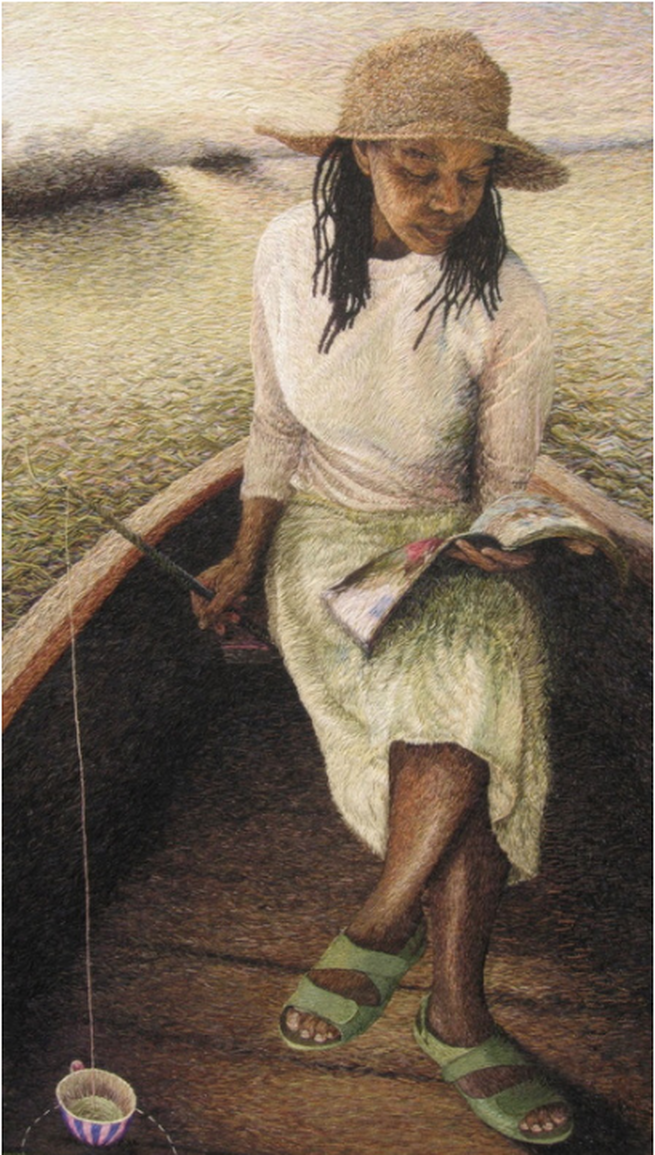

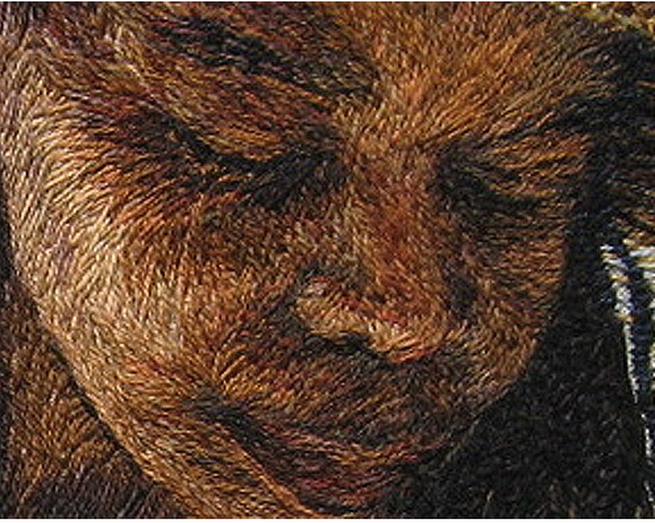

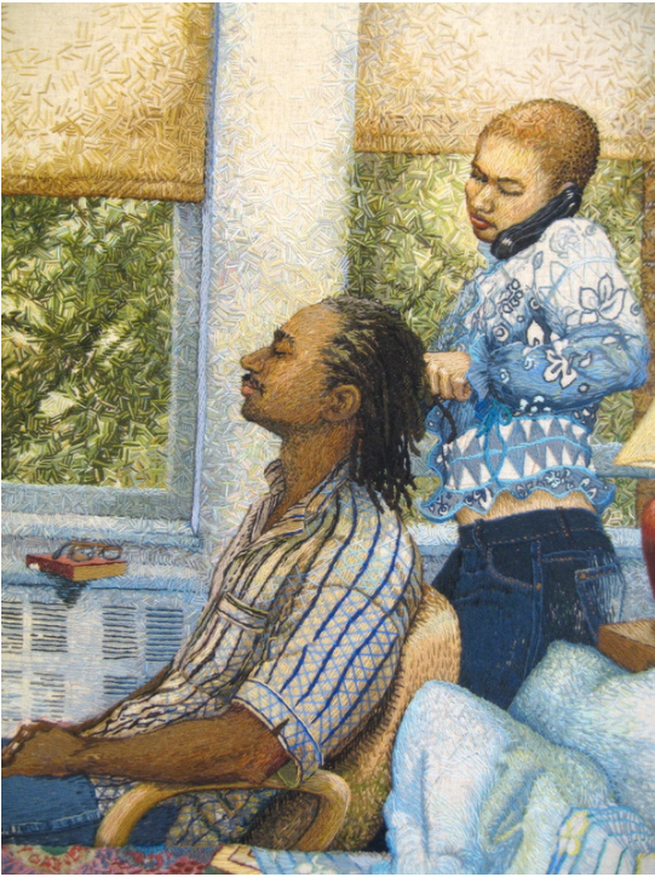

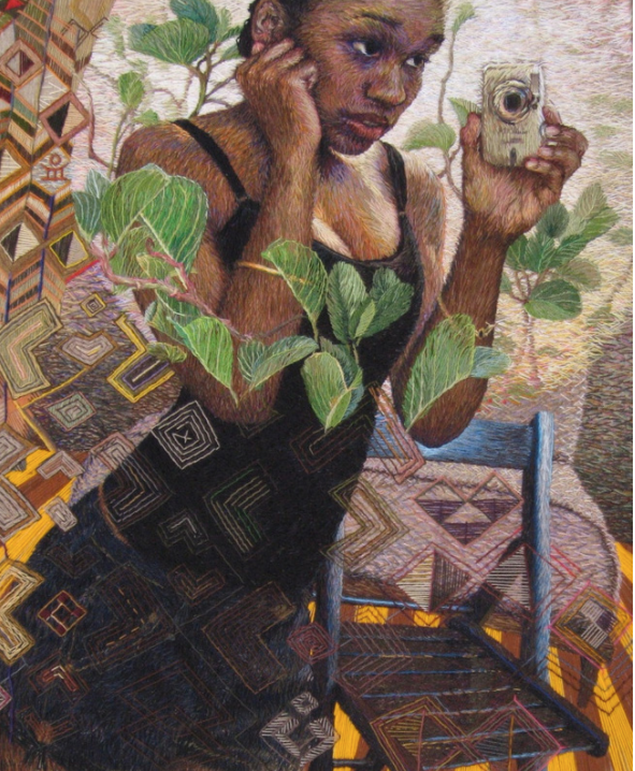

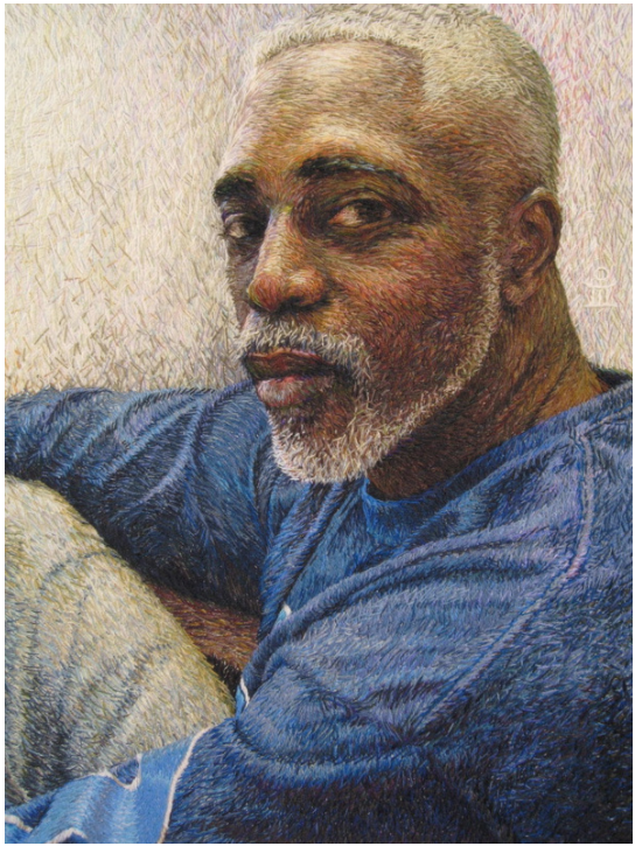

Miller’s pieces don’t take quite that long, but she does profess that the average piece takes 9 months to produce, and she spends as long as a year and a half on the larger ones. That’s with a schedule of sewing about five hours a day, five days a week. “If I thought about how long it would take, I probably wouldn’t do it,” she says. “It’s like doing a puzzle; you don’t think about how long it will take you. You just think about the thrill of the search.” It’s a much longer “search” than the average artist in other art forms—painting, drawing or writing. Because every tapestry takes such a long time to make, subjects take on a focused air. The artist was committed, for quite a length of time, to capturing a moment. In the Bayeux Tapestry, it’s the Battle of Hastings, a moment important to the Norman Conquest of England. It’s the moment when the English monarchy, still intact today, began. It’s easy for us to see why the artist wanted to share that moment with generations to come. What makes Miller’s works all-the-more interesting are her subjects. She doesn’t embroider battles or knights or princesses. She focuses on people. People combing hair, people talking on the phone, people glancing at something outside of frame. Miller says, “I thought about my own interior life… I’m addressing it for myself, and it happens universally.”

She finds inspiration in a young girl capturing a photo, a woman drinking tea, a laugh, a smile. These simple gestures take on a grand importance, a gravity even, that just isn’t tangible in a painting or a sketch. The works feel much more intentional, much more purposeful, if only because we realize how much time the artist spent making them.

Miller’s thread art has a pulse. Skin tones take on a feathery quality, making the subjects feel alive. In pieces like “The Impossible Dream is the Gateway to Self-Love,” where Miller has to carefully choose where each color goes, you can be surprised what colors jump out. She works from a palette that numbers in the thousands of hues. It makes them feel alive. In amongst the chocolates and charcoals and beiges, there might be a stray blue thread. They have a soul. The constraints of embroidery mean that Miller will never be as prolific as Picasso, but that doesn’t matter to her. Her art is simply a way of sharing her views with the world. “I want people to see that art is a way to life itself… Whatever grabs you about a singer, they’re making their heart visible to you.” Ruth Miller’s works hang in private collections and museums across the United States. You can find one of her pieces, "The Path to Enlightenment" on display at the Smith & Lens Gallery through October 22, 2017. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed