A day-trip to Biloxi nets a rich catch of history, culture and delicious meals - seafood, of course!

- story by Karen Fineran, photos Karen Fineran and courtesy Visit Mississippi Gulf Coast and the Mississippi Gulf Coast Museum of Historical Photography

Biloxi Maritime and Seafood Industry Museum

The museum, site of the former Mississippi Naval Coast Guard Base, was established in 1986, was completely reconstructed after it was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, and was then reopened on its original site in 2014.

The Maritime Museum documents the history of Biloxi’s seafood industry, through hundreds of one-of-a-kind exhibits and artifacts about shrimping, oystering, recreational fishing, wetlands, managing marine resources, marine blacksmithing, boat building, net-making, harvesting techniques and technology and seafood marketing - all the while telling the tale of over 300 years of Gulf Coast history, culture and heritage. Sharing the spotlight is the history of recreational boating, the shipbuilders who still work the craft, and Katrina and other hurricanes that changed the landscape, but not the resolve of people to live near the water. Set next to the pristine park and festival ground of Point Cadet, the three-story museum creates an imposing first impression, with its triangular wall of glass windows facing the Bay. We were surprised at the size of the museum. An easy way to see the entire museum without missing anything is to start on the third floor and work your way down. An added benefit is that the views of the Biloxi Bay Bridge through the glass windows are breathtaking. There are indoor blue lights that shine upon the Nydia at night, and when you’re coming back to Biloxi from Ocean Springs, you can look over the bridge and see the ship through the glass walls. It seems almost like she’s sailing in the evening light.

Displays and text commentary bring to life other aspects of the industry, including cleaning, packing and shipping the seafood, and the environmental impacts of weather and pollution upon the seafood industry.

My friend and I particularly enjoyed exhibits that showed how hard labor (and rusty oyster buckets) eventually gave way to new technologies and machinery that make working in the industry easier. For example, the shrimp-peeling machine, introduced in the 1970s, can peel about 1,000 pounds of shrimp in just one hour. That replaced the work of about 150 workers.

Another impressive item on display is the Ship Island Lighthouse lens. This Fresnel lens was made in the late 1800s in Paris, and was in the old museum when Katrina hit in 2005. The lens is made of several prisms, and the prisms scattered after the storm. Eventually, every prism was found and the lens was restored, keeping the scratches and chips that the hurricane left on the prisms as “battle scars.”

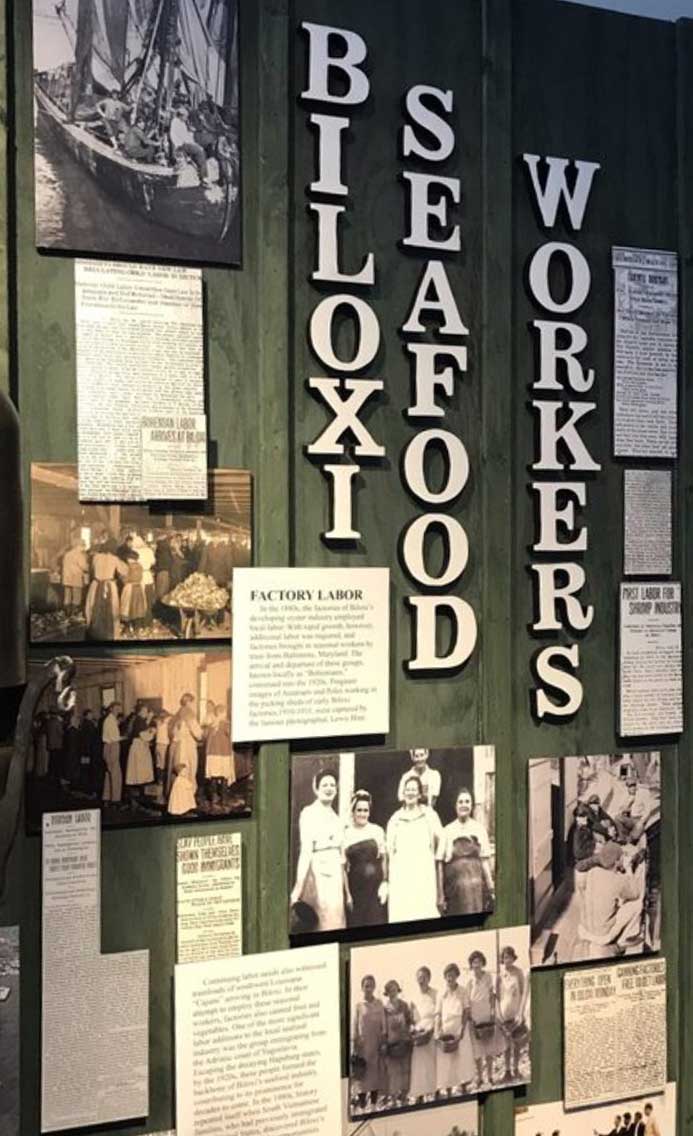

The museum’s unrivaled collection of vintage photos tells the heritage of the seafood story from the time of the first Indian settlement through generations of immigrants whose journeys contributed to the Coast’s melting pot culture.

Photographs, anecdotal stories, video clips, and theater movies give insight into the seafood workers’ lives, their hard work and their inventiveness. Their weary, sweat-drenched faces bring home just what a laborious occupation the seafood industry was and is. Historically, the success of the seafood harvest was dependent on the entire family. The male members of a household were boat owners or fishermen, while women and children of the family usually worked in the factories. Young children worked alongside adults, until a 1908 Mississippi law made it illegal to hire children under age 12 to work in factories.

Like any place where hard work could yield fortune, Biloxi’s seafood industry attracted immigrant labor – first the Polish (by way of Baltimore), then the Croatians and Cajuns, and more recently, the Vietnamese, who were first brought here by local fishermen in the 1970s. In time, these ethnic groups were able to buy their own boats and make their own business, cultural and culinary contributions to Biloxi.

A new exhibit dips deeply into the history of the Croatians, Yugoslovians, French, Vietnamese and other immigrants who came to work in the seafood industry. Their more than 400 stories are told in a permanent exhibit on five computers set up in a dedicated room on the second floor of the museum. Icons on the computer screens display various categories of individuals and companies that have been inducted into the Maritime Hall of Fame which recognizes outstanding citizens and their contributions to the seafood industry. Visitors can choose to view any story that piques their interest.

Don’t miss the “hurricane gallery,” with its continuously running informational movie about the devastation of hurricanes on the Coast. And take the time to walk around the outside grounds, where, among other things, you can take a walk around a World War II submarine and the beautiful Golden Fisherman statue.

The new seven-foot bronze Golden Fisherman statue was erected and dedicated just this spring on the lawn of the Maritime Museum, casting his famous net toward Biloxi Bay.

Crafted in Parma, Italy, before being shipped to Biloxi, the Golden Fisherman stands on a 6-foot granite base with plaques naming more than 800 seafood industry families. The base also includes the names of the kings and queens from the annual Biloxi Shrimp Festival and Blessing of the Fleet.

The story of the original statue which it replaced is an interesting one. Erected in 1977, that statue was much larger, at fifteen feet high, casting a twenty-foot net, and weighing in at a ton. In 2002, the monument was moved from the Vieux Marche Mall to Point Cadet near the museum, where the statue cast his net toward Biloxi Bay.

When Hurricane Katrina struck in August 2005, the storm surge broke the Fisherman's foot and he toppled, falling upside down. (The museum, a couple of miles from the statue, washed away.) Only a week after the city moved the Fisherman to the former museum location, someone stole the statue in June 2006. Rewards of up to $15,000 were offered. The headless statute was found days later in a creek in Mobile County, Alabama. The fisherman's body had been dismembered, but the parts couldn't be sold as scrap because the statue was made of an alloy. The thief was arrested, and the Fisherman's remains returned to Biloxi. Because the damage from the hurricane and the theft made it impossible to save the original statue, parts of it will be used for ornamental work that will be placed in a fountain to be built in the next phase of the Golden Fisherman project.

A visit to the Maritime Museum makes for a fairly full morning. In fact, if they watched all the videos and read all the placards, a family could easily spend two to three hours here. At $10 for adults, $8 for seniors and military or AAA, and $6 for children, we thought this attraction was really worthwhile for visitors and locals alike!

The Maritime Museum, a testament to the strength and resilience of the people who have made the Gulf Coast what it is today, is open every day, Monday through Saturday from 9am to 4:30pm and Sunday from 12pm to 4:30pm. A Dash of History of the “Seafood Capital of the World”

Before Biloxi was known as a casino play-land, it proudly wore its crown of Seafood Capital of the World, a place of communities built on shrimp nets and oyster dredgers. Gulf Coast residents have always enjoyed the bounty of the seafood harvest, but it took awhile to spread its wealth outside the Gulf Coast.

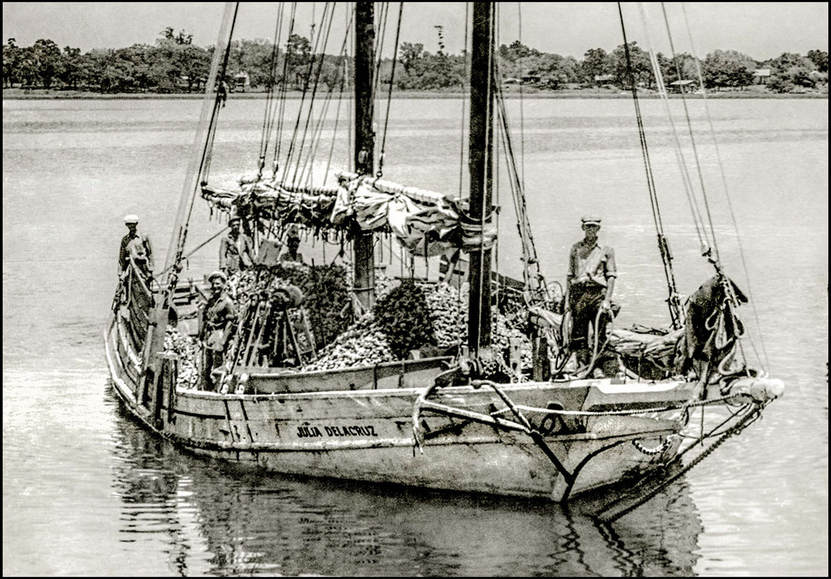

In the nineteenth century, the Biloxi seafood industry supplied only local markets with its succulent shrimp and oysters. Seafood would spoil before it could be shipped far inland. All the same, with the burgeoning tourist trade from New Orleans, there was a ready market in wait. The opening of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad line in 1870 connected the cities of New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, and made it possible to ship seafood out and bring more tourists in. And finally, artificially created ice had been invented in the mid-19th century, so that broader commercialization of Biloxi’s seafood industry could finally become possible. The first oyster packing enterprise in Biloxi was the Lopez, Elmer & Company seafood plant, which opened at the foot of Reynoir Street in 1881, on Back Bay Biloxi. It canned oysters and shrimp and offered raw oysters in bulk. Biloxi factory owners began turning their eyes toward Baltimore, Maryland, an already booming seafood processing area, to learn about its new and revolutionary oyster and shrimp canning methods. Upon visiting Baltimore, they discovered that the factories there used a seasonal labor pool, the “Bohemians” or Polish workers. Upon returning to Biloxi in the 1890s, the factory owners initiated many of the new techniques, and brought in many workers of the migrant Bohemians from Baltimore. Rows of shotgun clapboard houses at Point Cadet, collectively referred to as camps, had been built by the factories’ owners to lodge the seasonal workers, christened by locals as “Hotel d’Bohemia.” Biloxi’s population doubled with the workers who came to process the plentiful catches of shrimp and oysters at the factories. The workers’ wages were extremely low, since the cost of their transportation to Biloxi from their original homes was deducted from their wages. The seafood industry continued to expand in Biloxi as fishermen heavily harvested the bounty of the gulf, bays and bayous. By 1902, Biloxi’s seafood catch numbers were skyrocketing, and by 1903, Biloxi, with a population of approximately 8,000, was referred to as “The Seafood Capital of the World.” According the Mississippi History Now website, “Seafood cannery owners sent out their boats, beautiful “white-winged” Biloxi schooners and others, to ply the waters for their bounties… The seafood workers who packed the catches and the fishermen who caught the shrimp and tonged the oysters were usually not able to afford their own boats, therefore, factory owners owned and controlled the fleets and harvests." You can read more about the history of Biloxi’s fishing industry here. Although much has changed through the century, the seafood industry continues to play an important role in Biloxi’s local economy. Worldwide demand for fresh and processed seafood, especially shrimp, continues to grow, and it is unlikely that, even given the influence of unexpected natural or manmade disasters like the 2010 BP oil spill, we will ever see the end of the shrimping industry here on the Gulf Coast. A Restful Seafood Lunch

After so much time on our feet, Amy and I were ready for a lunch break, and decided upon the nearby Wentzel’s Seafood, at 1906 Beach Boulevard. I had heard that the executive chef had been mentored by Chef Bill Vrazel of Vrazel’s Restaurant in Gulfport, and that the French, Creole and Italian food at Wentzel’s –in particular the lunch specials – was worth checking out.

Our server Pam could not have been more friendly or attentive, as she brought us crusty French loaves with soft butter. We each got a frosty pint of IPA and picked our entrees from Wentzel’s special lunch menu, with all of the entrees priced at between $10 and $14. My friend stuck with our day’s shrimp theme, and her shrimp poboy arrived stacked high with crisp hand-battered shrimp, served with a Caesar salad. I was drawn to the New Orleans styled “select entrees,” finally settling upon the Flounder La Crab – a paneed portion of flounder, generously topped with huge lumps of jumbo crabmeat, served with grilled broccolini, and all topped with a beurre blanc sauce. It might have been a little bit rich for the middle of the day, but I wasn’t complaining. Our Seafood Education Continues on the Water

What could be a better finale to a day dedicated to shrimp than to take the “Biloxi Shrimp Boat Tour” with the Biloxi Cruise Company, and its founder and owner Captain Mike Moore.

You’ll find the Biloxi Shrimp Boat Tour at the Biloxi Small Craft Harbor on Highway 90, east of the Commercial Docking Facility and the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino. The Harbor houses many other smaller commercial boats that engage in charters and tours, a boat ramp, public restroom and showers, plenty of parking and over 140 boat slips.

Reservations are recommended for the Shrimp Boat Tour, but if there is space, you will be warmly welcomed aboard by Captain Mike or Captain David, and the boat mascot, a friendly and peppy black Labrador named “T.J. the Boat Dog.”

T.J. greets all the guests, wanders up and down the stairs between the two boat levels, and, in cooler weather than this day’s, wears a little vest filled with water, sodas and beers. T.J. is the bartender that sells beverages to the guests onboard, after they slide their money into his vest.

Captain Mike Moore bought the 1953-built tour boat in 2006 and, for the last 12 years, he has operated a continuously-running educational shrimping tour, that leaves three times a day for seven days a week. Before buying the boat, Moore came from a commercial shrimping and seafood family and was a charter boat captain for fifteen years.

The 70-minute tour takes place inside the Mississippi Sound, so the boat never actually heads out into open water. The water is protected by Deer Island and oyster reefs and the ride isn’t at all choppy. Being the end of July, the weather was more than a bit warm, but the crew slid open the windows below for cooling breezes, and invited passengers to climb to the upper level (sun hats are recommended). Seagulls swirl and dive behind the boat the entire way.

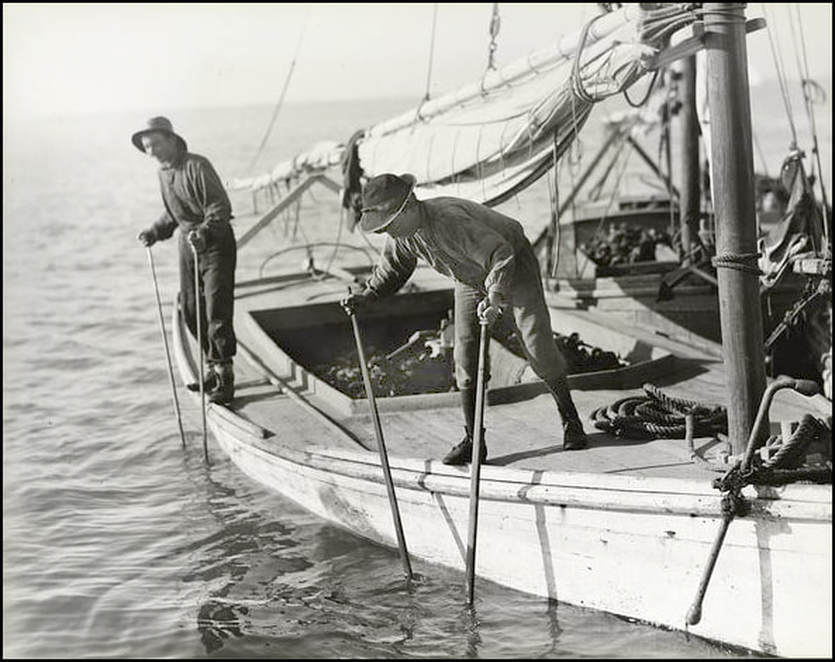

As the boat chugs out for about half an hour dragging a net (a “try trawl,” a smaller sized net stretched across a trawl board), the Captain and crew explained various facets of shrimping, including the types of shrimp, shrimp seasons, migratory patterns, and anatomy.

For example, we learned that shrimp migrate about 400 miles in a circle. We also learned that shrimp can smell with their antennas, can see 360 degrees with each of their eyes, and they only live about two years because of the amount of predators in the waters – but that’s okay, because they can lay up to a million eggs per shrimp. We learned also that the cost of fuel generally accounts for about half of the costs to operate a shrimping vessel. About 75 percent of Mississippi’s shrimp harvest is brown shrimp, which are usually most abundant from May to August. They congregate in water between 15-120 feet deep and are caught mostly at night. When the brown shrimp season comes to an end, the sweeter-tasting white shrimp move in and take over in the fall, from around September through the end of the year (or whenever it first freezes). Found in shallow water, usually no deeper than 90 feet, white shrimp are caught mostly during daylight hours.

After Captain Mike pulled up the net, he sifted through and examined about two pounds of shrimp and various small sea creatures that the net had pulled up, describing and explaining the significance and features of each animal.

This is the same method, Moore explained, that data analyst specialists from the state use to determine when shrimp season should open, except that they are required to go out much further and to pull up a new “try trawl” every 15 minutes or so to examine its contents.

Our catch on this day was interesting and varied. In addition to (surprise) some shrimp, we also pulled in a variety of small fish such as pinfish, flounder, a pufferfish, tang fish, surgeonfish, speckled trout, catfish, sheepshead, skipjack, kingfish, whitings, blue crabs, a hogchoker and even a squid.

I got a kick out of learning about the hogchoker, which is a small brown “trash” flatfish traditionally used as hogfeed, but would unfortunately choke and suffocate the very pigs trying to eat their bony bodies. After the net was emptied and sifted through, the creatures were put into an onboard aquarium for further view. We were invited to get up close to peer inside the tank and view the animals, one by one, as they were pulled out of the tank and explained to us. The Captain demonstrated how to squeeze the black ink out of a squid to pour over his hands and into the tank, before revealing the hard plastic-like quill that made up its innards. Many of the kids enjoyed handling and touching some of the more non-harmful creatures.

Once the small creatures are adequately perused by the passengers, they are all thrown back alive into their watery home. Captain Mike explained that, because it is a tour boat, they are not permitted to keep any shrimp or fish that they catch (on a typical day, he may bring up 10-15 pounds per drag, and on some days, he has brought up to 100 pounds per drag).

This is a very kid-friendly tour, and in fact, even pets are allowed (as long as they’ll get along with T.J.) Being geared toward families with children, we felt the tour packed enough educational value about the shrimping industry that it was a good value at $16 per adult and $11 per child. Tours leave at 10:30am, 1:30pm and 3:30pm every day of the week. Reservations are recommended. Thinking back upon the day’s outing, it struck me that life on the Mississippi Coast comes with its advantages – and nobody can say that Gulf Coast shrimp ain’t one of them. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed