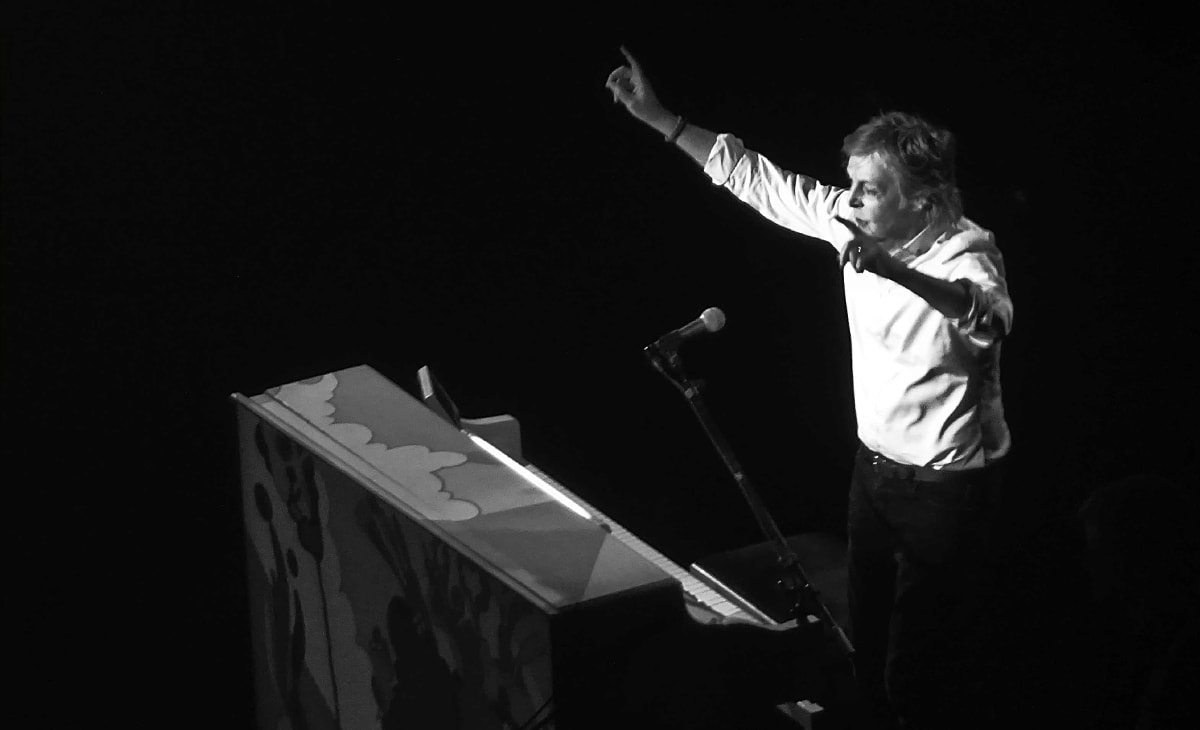

After fifty years of adoration, a Paul McCartney fan shares an intimate moment with him - along with 18,000 other fans.

- story by Ellis Anderson

While my dad was a church elder, he was a lively 42 years old in 1964 and possessed an extremely curious nature - and a love of puns. The band’s name caught his fancy as much as their advanced press. I could tell he was looking forward to seeing the Beatles as much as me and my older sister, Diane. My family didn’t live very far from the church, but Daddy drove faster than usual. He turned on our clunky console set as soon as we got in the front door.

My mom served us all pound cake and milk before settling on the sofa next to Daddy. Hailing from deep Appalachia, she generally viewed any new trend like the Beatles with suspicion; if something was fun it was likely to be an instrument of Satan. Like rock n’ roll. And mini-skirts. On the other hand, she felt a great fondness for Elvis. One of the Jordanaires who backed up Elvis was Ray Walker and Ray was a leading member of our denomination. That fact completely offset Elvis’s devilish hip-swiveling routines. Mom was sure Ray would convert Elvis any day now. She could just tell by Elvis’s rendition of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” that he’d eventually choose the straight and narrow path – ours. The one where any dancing at all was a sin. Diane, seven years older than me and an actual teenager, possessed reams of Beatles knowledge she reeled off while we waited for the show to start. John was married with a son while the rest were single. There’d been an earlier drummer before Ringo, Pete Best. By the way, Ringo’s real name was Richard Starkey.

She and I nested on the floor right in front of the TV, ignoring our mom’s warning that the radiation would zap us blind if we sat that close. At the time, no one realized I was already legally blind. From sofa distance, all I could see on the TV screen were grey blobs moving around. I thought the world was blurry for everyone, and that while the extra radiation made things clearer on TV when I sat close, it was a dangerous habit. That night, the risk seemed worth a lifetime of darkness. When the Beatles began playing against a backdrop of shrill screams, the bright sounds that flooded my ears were unlike any I’d heard before. The supremely simple songs weren’t overwrought with croons and warbles and horns and back-up singers. Yet the music kicked up its heels, unlike the time-worn tunes by the forlorn folk singers I admired. The four cute boys on stage wearing preppy suits and jumbo-bowl haircuts performed their songs with unpretentious energy and merry spirits. I sat mesmerized, wanting the music never to end.

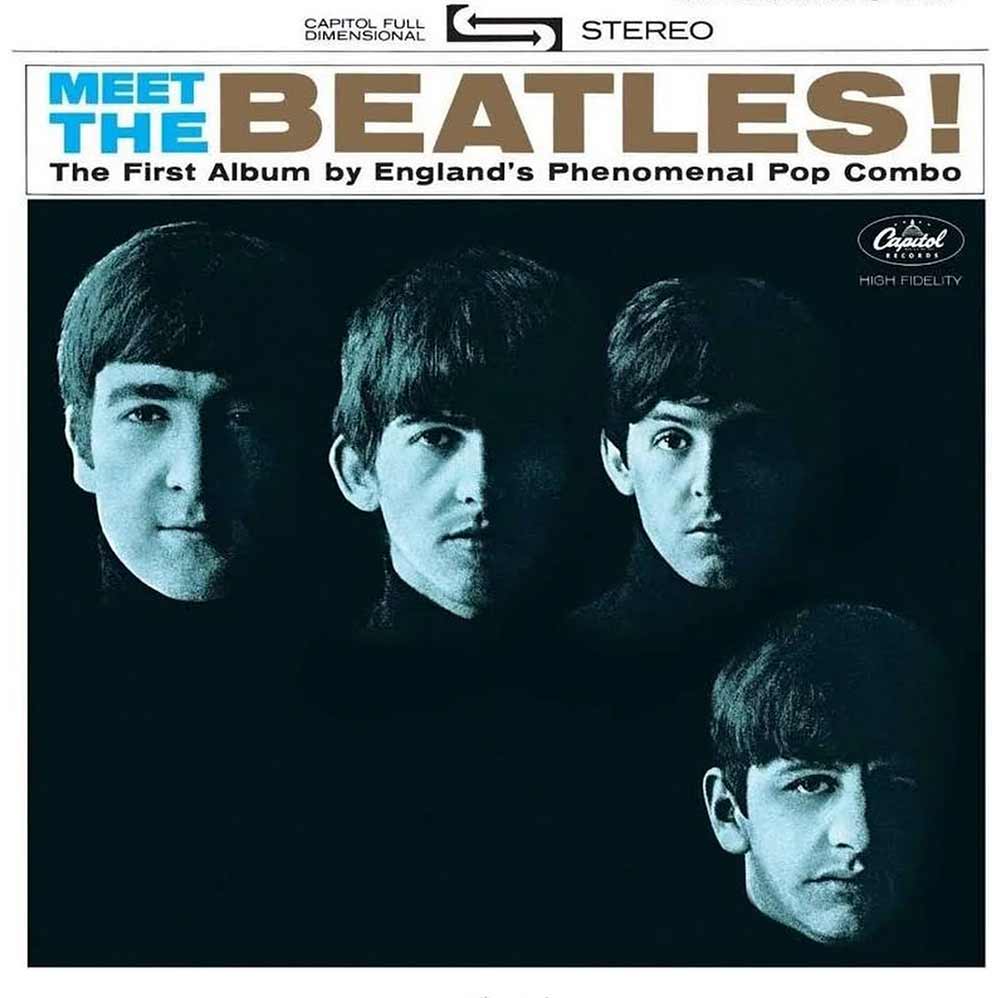

My sister helped make that happen. She used some of her baby-sitting money the following week to buy the Brits’ first album, “Meet the Beatles.”

Passion overtook me one afternoon while I listened to the album alone, mooning over the stark blue tinted faces on the cover. I circled the handsome head of my beloved and wrote – in ballpoint pen – “I Love You, Paul!”

Diane was apoplectic when she saw it a few days later.

“You idiot!” she screamed. “You not only ruined the album cover, you wrote on John’s picture!” She was right. I’d gotten the two singers confused. My embarrassment lasted until the album was lost in a move decades later. “I haven’t forgotten,” Diane says now when I remind her of the incident. “But I have forgiven you.” There’s a little edge in her voice that makes me wonder. After the album cover incident, Diane’s attraction to the Beatles faded. Her devotion to Elvis redoubled as his acting career soared. So my sister never learned of more serious damage to her album. Since my school let out hours before hers, I’d spend afternoons quietly playing the album in her room on her portable record player. Over and over and over. I learned the words to every song. While I adored the songs, there was a greater purpose to my memorization. Somehow, at some point in the future when I was an actual woman, Paul and I would have a chance meeting. The details were fuzzy in my fantasy, but he’d invite me to sing with him. Our voices would harmonize perfectly on every tune, our tones becoming twins. His heart would instantly be mine forever. That was my destiny. I just knew it. But by the time I'd learned all the songs, word for word, deep grooves in the vinyl distorted the sound. The crackle and hiss of scratches marred those clear, dear voices. I repeated the same crime 15 years later.

As a college student learning to play the song “Blackbird” in my little studio apartment in Nashville, I played the White Album song repeatedly. After finding one of the fingerings on the neck of my guitar, I’d put it aside, stand up and go to the record player, pick up the stylus and move it back. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Forty years later, the price of a new album seems a small price to have paid for learning the song that’s brought me so much joy, so many times. With that mysterious musicians’ alchemy, my hands seem to have brains of their own when I play it. They move independently, without conscious direction from me. Sometimes I watch as if they’re someone else’s hands. The left hand scoots up and down the guitar's fretboard, putting pressure on this string and that, while the right hand plucks the proper strings at a precise moment needed to create Blackbird’s melody. How do they do that? I don’t know. Playing an instrument eventually becomes a miraculous process that by-passes the ego, connecting the player’s soul directly to a universal power. I believe all musicians feel this. It gives us a joy like no other. It’s the reason we’re always encouraging kids to take up an instrument. Paul and I never did meet and Linda snatched him up before I made it out of middle school. The only time we’ve been in the same room – if you can call it that – is when he played in New Orleans this May. A nosebleed seat turned out to be a great advantage, giving me a stupendous overview of the event. We didn’t need front row seats to catch the good will the former Beatle radiated. And I finally got my invitation to harmonize with Paul. Along with 18,000 other people, I lifted my voice as he led us all in song. I hadn’t been the only one wearing out the albums. We all knew the words. The intensity of the show wrung tears from my friend and me several times. Glancing around, I saw tissues dabbing at eyes everywhere. And then Paul played Blackbird. Alone on a darkened stage, he fingered the acoustic guitar with utmost confidence. He knew the brains in his hands were not going to falter. I struggled not to sob because it’d shake my own hands that held a phone, capturing the moment for me. Crisp and pure, each perfect chording became a sweet spear that pierced my heart. When Paul finished the song and the roars had died back, he asked the audience, “How many of you tried to learn how to play Blackbird?” A surprising number of hands shot up all across the stadium. Maybe one in ten. Paul laughed. “And you never got it quite right, did you?” he asked. We all laughed with him. It was true. Even though I’d worn out a record learning, I had caught a few notes in the songwriter’s performance that differed from my own version. But "Blackbird" isn't a song about perfection. It's about having broken wings and still being able to fly.

Dedicated to Jeannette Bolte, who made the experience possible (and was the perfect concert companion), and to Bill Morrison, who sacrificed his own concert ticket to me in the interest of journalism!

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed