What Katy Did

Award-winning author Rheta Grimsley Johnson introduces a moving new book by noted journalist John Branston.

“Watch out for snakes!” I warned.

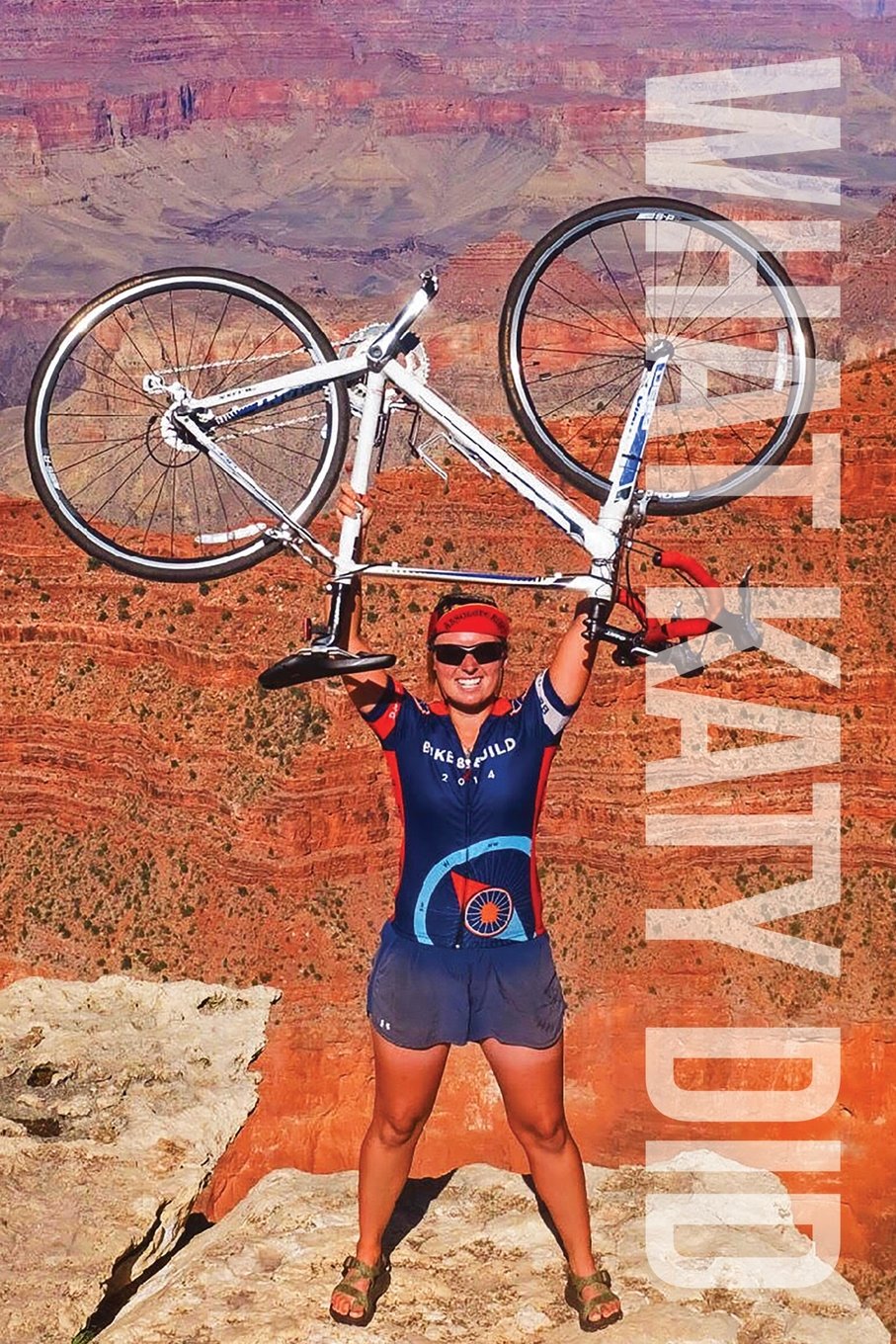

“Kaboom!” yelled the dam-destroyers. They were fearless. That’s where I’ll keep Katy Branston. In the hollow, in the branch, in the box of faded snapshots under the bed. For somewhere there is a photograph I took of her that dam-building day. She is standing with her father, mother and brother, on the side deck where I’d line them all up each annual visit. The Branstons, a handsome couple, had such beautiful children that you felt compelled to document their big eyes and pinch-able cheeks. I once tried to sell my publisher on a photograph of Katy’s brother Jack for a book cover. I am talking cute. In 2014 I received an email from Katy announcing she was leading a bike tour across America to raise money for something called “Bike and Build.” It was a fundraising scheme for affordable housing that involved pedaling nearly 4,000 miles in 75 days. Once again, I marveled at time’s swift passage. Little Katy was grown and gone, already graduated summa cum laude from North Carolina’s Elon College and living near her brother in Montana. For a while that year I was current. Katy blogged about the trip, and I saw a few photographs and read well-written accounts of her adventures. She made it safely with her 32 charges to the Pacific Ocean. Still fearless, I thought. But this past November when Katy’s father, John, called to tell me she had taken her own life, I refused to believe Katy was age 29; it simply could not be. She was the small girl in overalls. Now, because life is so damn tough, there’s a book you should read, as close to the bone as anything ever written. Titled What Katy Did, it also is what John did after his daughter died. He wrote, same as he’s done every day of his adult life. Katy had started writing a book and wanted to share it with friends and family when she turned 30, which should have been this month. John finished it for her.

John and Jenny Branston have been in my life since 1981, when John and I worked in a small bureau for United Press International in Jackson. No, we didn’t deliver packages in a brown truck as many assumed. UPI, not UPS. We were reporters -- young, driven, competitive. He was a Michigan Yankee. I was Deep South. But we were good friends.

We even took jobs with the Memphis newspaper the same day, sharing the ride up from Jackson for our respective interviews. We both eventually left that paper, but print journalism had its hooks in us. The Branstons named their firstborn, Jack, after Jack Burden, the reporter in All the King’s Men. John, an exceptionally fine writer, authored a well-received book, worked for Memphis magazine and, for years, the alternative city paper. I have seen the Branstons more lately than I have in decades. John had retired, was a bit restless, and he and Jenny visited us in the Pass. They fell in love with the place. It happens. Before we knew it, they bought a second home on Second Street previously owned by a lady named Gisela who grew up in Nazi Germany and survived Kristallnacht. The Branstons started giving the house the clever decorating touches that Jenny is famous for in Memphis. John rejoiced in doing some physical work for a change. Then they lost Katy, who never saw the new family home in the Pass. She never saw Cat Island in the distance, or up close, the siren sight that convinced her father to locate here. I knew for certain that John, living through the worst imaginable thing any parent could face, would write something. He would have to. It is how writers work through everything, joyful or bleak. Especially for reporters, it isn’t real until it appears on the page in short declarative sentences. “This is a short book that can be read in an hour or two,” John writes, “which is fine because that’s about all I have in the tank and Katy wouldn’t want us moping around. Katy believed in living true….” It may be short, but it is perhaps the most profoundly heart-breaking story of struggle I’ve ever read. Written by a seasoned journalist, it is full of evocative, but never maudlin, details that make Katy as real to me as she was that day in the branch. She taught herself to play the ukulele. She worked for Habitat for Humanity in Whitefish, Montana. She faced down a mountain lion. She missed her folks. Using his own words, Katy’s words, her friends’ countless tributes, John has managed to lasso his sorrow into what may be the single best profile I’ve ever read. “It is possible to have a life after horror and loss,” John concludes. “Gisela lived 77 years after escaping the Nazis. Walter Anderson was most productive after escaping from the state mental hospital. Pass Christian completely rebuilt itself after deadly hurricanes in 1969 and 2005. I have hopes.” He is following his daughter’s example. Living true. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed