From Civil War to Civil Rights

Award-winning author and syndicated columnist Rheta Grimsley Johnson reflects on her childhood in Alabama and a trail that sheds light on the state's history.

It amazes me to consider that we were, coincidentally, walking what is now called the Alabama Civil Rights Trail. We took scant notice.

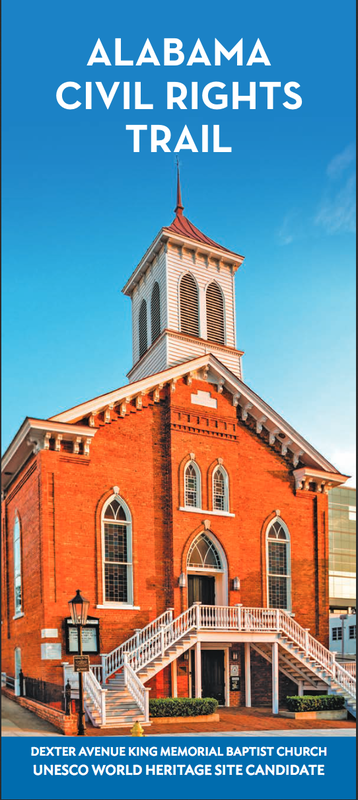

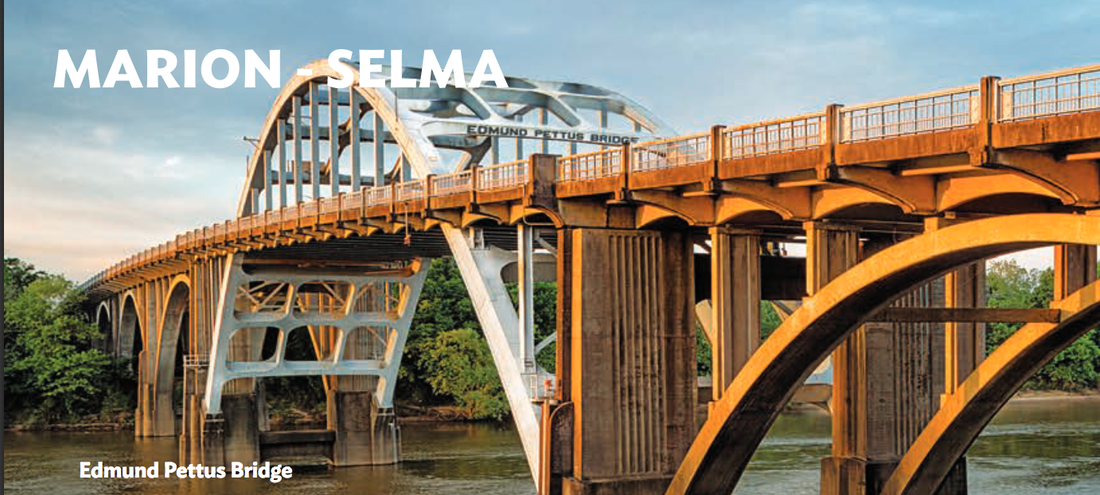

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin Luther King’s church, was a block from the capitol where we ate our noodles and looked at the bronzed spot where Jeff Davis had been sworn in as President of the Confederacy. Rosa Parks had been arrested a few more blocks away. The famous Montgomery bus boycott she had launched meant black citizens had pounded the same streets we were holiday strolling. Mother never mentioned that. History was being made in real time as we ducked and covered in our quiet suburban house and avoided downtown most of the time, except when we had company. Especially after 1965. The Selma to Montgomery March was on the Huntley-Brinkley every night for a month or so when I was 12. Bloody Sunday went down on a bridge named for a U.S. senator from Selma, Edmund Pettus. He’d been a decorated Confederate officer in the war, a Klan leader during Reconstruction and dead a long while when they named the bridge for him. There’s been a recent effort to rename the Edmund Pettus Bridge something else. But, then, you’d have to rename much of the South if you exorcised all segregationists.

When you visit Selma today, it is rare not to encounter a tourist or two walking across the bridge in a pedestrian lane. At the foot of the bridge on the east side are homemade tributes to the movement. There’s a “Tomb of the Unknown Slave” and a “Tomb of the Unknown Solider” beneath metal stars that hang haphazardly from a tree.

The National Park Service Interpretive Center is at the other end. And also the town of Selma, which, if I may speak truthfully, looks more tired than sleepy. It is full of empty storefronts and bored young people, no different from dozens of other towns in Alabama’s depressed Black Belt. The movie “Selma” must have brought excitement, and the 50th anniversary last year of the march when the President came to town. But now the movie stars and heavyweight politicians have gone away. The town is quiet. And most of us who walk the bridge are just passing through. Selma, of course, is on the official Alabama Civil Rights Trail, and any mother bent on educating her children, white or black, cannot ignore sites that UNESCO World Heritage Sites recognizes, or places with names so familiar they are part of our national subconsciousness. From Civil War to Civil Rights, the long, slow march of awareness stumbles on. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed