If you're excited about the possibility of restored passenger rail service in Bay St. Louis, find out how it all began.

- by J. Michael Dumoulin

Close your eyes and imagine that you are 160 years or so in the past. You’re standing next to the live oak tree that was holding your swing. The tree, now only about 40 years old, has yet to grow the venerable, horizontal branches there today. The other park benches and the bandstand won’t be in place for another 130 years.

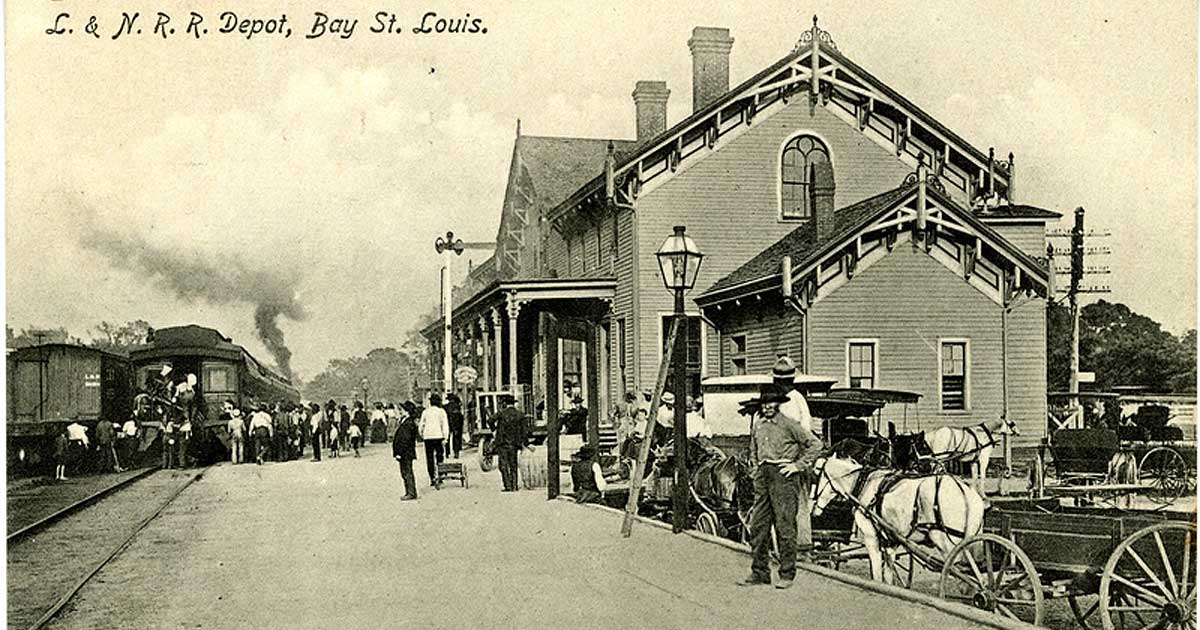

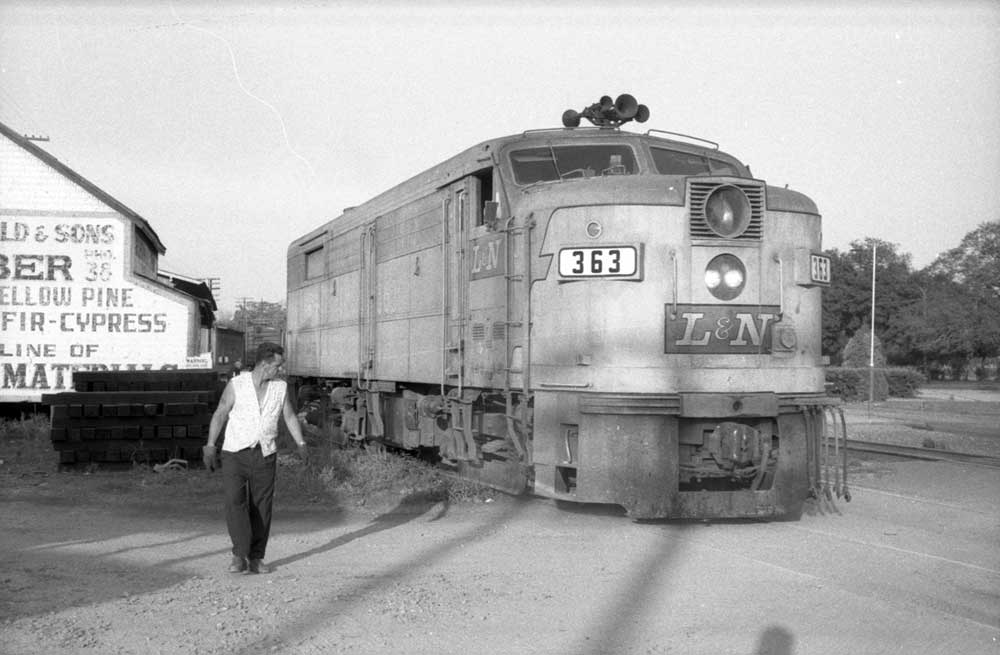

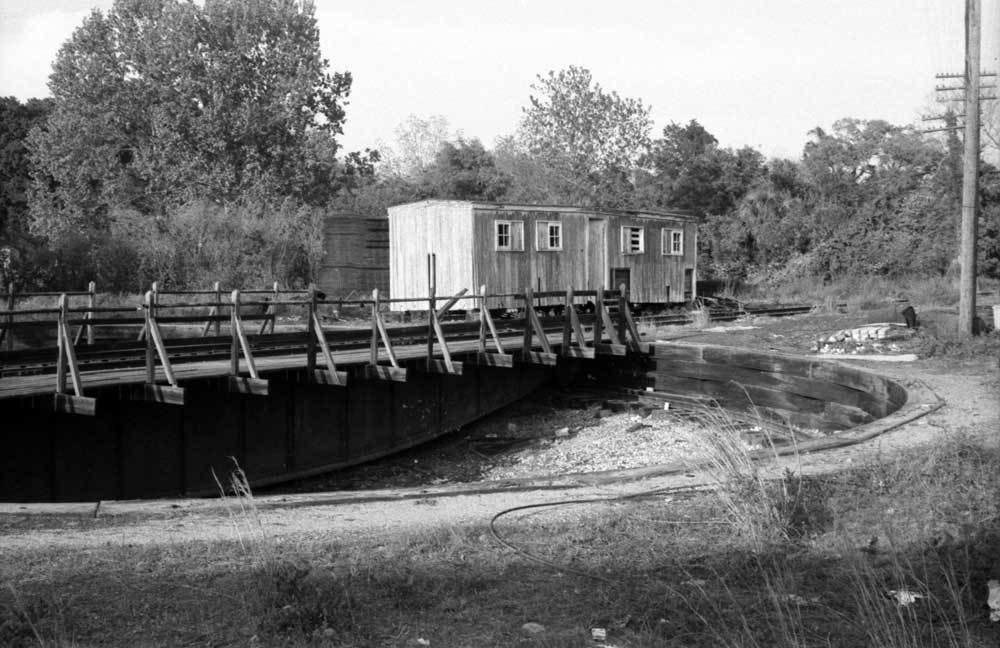

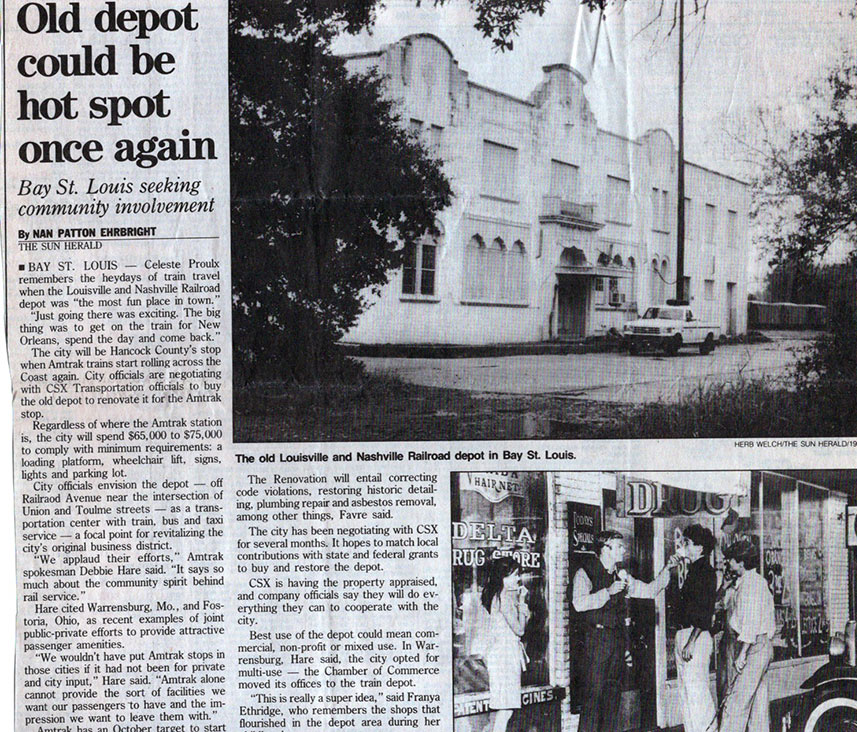

It’s 1862, and you’re standing at the fence line of a field in a patch of cotton, under the small oak, too young even to serve as a witness tree. Although an 1862 map of southern states’ railroads and stations in the Library of Congress shows that a rail line ran over the Saint Louis Bay, running from Mississippi City, across the Rigolets to New Orleans, here there’s no railroad, no depot, in sight. Back then, a rail line that passed through Bay Saint Louis was just wishful thinking. But in 1869, the newly-formed New Orleans, Mobile & Chattanooga Railroad made it a reality. They began berming swamps and cutting timber for rail ties, finally completing a 140-mile stretch of narrow gauge track from New Orleans to Mobile in late 1870. A year later, the company changed its name to the New Orleans, Mobile & Texas Railroad, presumably to focus on expanding the tracks to tap into opportunities further west. Opening a railway in the 1800s was as lucrative as starting a bank. Anyone with enough capital to buy the land and hire a rail crew could essentially open their own, exclusive toll road of rails and ties to connect their spur to someone else’s. Steam ship lines connecting the string of pearls of beach resorts that New Orleaners referred to as their “watering places” – Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi City, Gulfport, Biloxi, Ocean Springs, and Pascagoula – had already proven that money could be made here, so a group of entrepreneurs incorporated in Alabama and set their sights on profits from a direct passenger and freight line between Mobile Bay and the Mississippi River. By 1880, the connection proved profitable enough to attract the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. The L&N signed a lease to use the tracks and a year later bought the rail segment outright for $6 million in a mortgage foreclosure after the NOM&T defaulted on $4 million of interest payments to its bondholders (JXCO, Ms. Land Deed Bk. 5, p. 299). Almost immediately, the L&N converted the tracks from narrow to standard gauge, improving the ride and making the stretch compatible with other sections it owned. Over the next four years, the NOM&T Railroad built a number of stations along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Travelers could debark just over the Louisiana state border at Look Out, Claiborne and Toulma before reaching Wave Land (sic), Ulmanville, and Bay Saint Louis (listed as a major stop). Passengers heading farther east would then proceed past platforms at Henderson Point and Pass Christian, before traveling through Scott, Mississippi City and Beauvoir to Biloxi. To capture some of the traffic steaming out of New Orleans, Bay Saint Louis constructed and opened a train depot in 1876. It was a year of hope, the country’s centennial. The elegant BSL Depot soon became a favorite step-off for the Southern Pacific’s Sunset Limited and the New Orleans Commuter. Station vendors offered ice, oysters, pralines, and sandwiches to hot and hungry passengers. It was a hopping place: Locals would grab their parasols and put on their Sunday suits to meet the train just to people-watch. The BSL depot loaded coal into hungry locomotives and packed freight cars with everything from lumber and block ice to racing pigeons and locally bottled Crystal Ice soda pop. From its loading docks, the new depot and its rail yard operated a roundhouse, setting BSL up as a destination, not just a pass-through. In fact, the Bay Saint Louis depot kept its turntable operating well into the 1960s, when other L&N warehouses and smaller depots were already showing signs of wear or had been torn down. Like every public building in an era of segregation, the depot was divided. People were forced to queue up at separate white and colored ticket counters and stand in segregated waiting areas. Each passenger train traveling from New Orleans to Mobile hauled at least two passenger cars so that black and white travelers wouldn’t share bathrooms or closets or even store luggage next to each other. The segregation was barbaric and dehumanizing, but the brutal Jim Crow laws held sway across the South. If you wanted to travel by train, you had no choice but to comply – there was only one railroad. With such a monopoly, or perhaps because of it, the NOM&T could afford to double its passenger fare, and it 1877 they did so, by as much as a nickel a mile. It was big news; railway robbery! Up to that point, a New Orleans “commuter” could expect to pay $5 for a round trip to Pascagoula, $2.25 to BSL, and $2 to Mobile. (The Star of Pascagoula, April 6, 1877, p. 1) But just as railroads had decimated steamship traffic decades before, rail service eventually began to lose revenue to the automobile and motorized lorries, especially after the Old Spanish Trail highway (see “Old Spanish Trail, Gulf Coast Region,” by Dan Ellis, 2017) was paved in the 1910s. What started out as a marketing slogan for a group of highway segments, the Old Spanish Trail became U.S. Highway 90 in 1925, a two-lane ribbon of tar and concrete running from Jacksonville, Fla., through San Antonio to San Diego, Calif. Travelers now had a practical alternative to the Pullman punch ticket. In general, though, across the country “the rails” continued to be a relatively stable institution until the mid-20th century. By then, national airlines and the interstate highways had chipped away too many of the railroads’ passenger and cargo customers, forcing small railroads to merge into the few mega-rail companies we see today. L&N and the Seaboard Coast Line conglomerated a hundred years after acquiring the NOM&T and became Seaboard Systems in 1982. By the end of the 1980s, Seaboard Systems and a host of other railroads in turn had been gobbled up by an even larger rail system, Chessie Seaboard Consolidated, or CSX. You’ll see those initials on many of the train engines and rail cars that pass through the Bay Saint Louis station today. Daily passenger service to Bay Saint Louis ceased altogether in 1970, partly due to the Sunset Limited’s reputation for late arrivals (see “Gulf Coast Revival?,” Bob Johnson, Trains Magazine, September 2015), but mostly because of its lower ridership numbers and profitability. When Amtrak was born a year later as a national rail service, the New Orleans-to-Jacksonville segment just didn’t make the cut. Waveland and Bay Saint Louis passenger stations, already deteriorating, were all but abandoned. Then, in 1991, as an investment to attract tourists and re-invite New Orleans commuters, Bay Saint Louis purchased the depot and much of its surrounding property from CSX. The city began to aggressively redevelop the Depot District, completing repairs to the depot building itself in 1996.

Amtrak reestablished passenger services here in 1993, extending its Los Angeles-to-New Orleans Sunset Limited train route through Mississippi and Alabama to Jacksonville. But, alas, that service ceased in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina significantly damaged rail lines and bridges.

Open your eyes. You’re back sitting on that swing, or standing in the gazebo by today’s station. That whistle you hear is a CSX freight train passing down the tracks. Possibly as early as next year, rail passengers from New Orleans and Mobile are expected to begin visiting Bay Saint Louis once again. Two trains will probably arrive and leave the city’s depot every day. People probably won’t get those old-fashioned punch tickets and the fare will be more than $2.25 to step off the train and onto the platform, but I’m sure the locals will make it worth whatever the ticket will cost. Who knows, people around here might even grab their parasols and put on their Sunday best just to meet the train. Townspeople certainly did in 2016 when an Amtrak inspection train stopped at the depot! Great changes are afoot at the station – and across the street along Depot Row – as the city gears up for renewal of passenger rail service.

Part Two next month opens near the same swing bench and goes back in time, but with a twist, literally. With an over-the-shoulder glance, we’ll look across to Blaze Avenue and the Depot District, exploring how Bay Saint Louis’s once-commercial hub has changed since the 1880s

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed