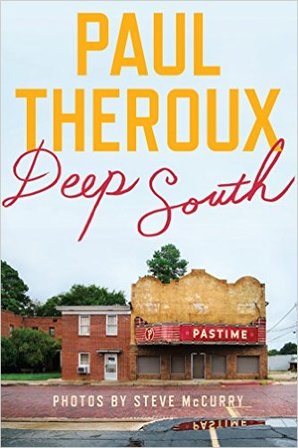

Theroux's “Deep South”

An iconic travel writer treads some old roads.

- by Carole McKellar

His latest nonfiction book, “Deep South,” was sent to me in October by Parnassus Books in Nashville, Tennessee. As a member of their First Editions Club, I receive a signed first edition twelve times a year. I almost always love the selections, but I was skeptical of a travel book about the south written by a curmudgeon like Theroux. I was pleasantly surprised by his appreciation of the landscape’s beauty and southerners' warmth.

Theroux writes, “After having seen the rest of the world, I had planned to take one long trip through the South in the autumn, before the presidential election of 2012, and write about it. But when that trip was over I wanted to go back, and I did so, leisurely in the winter, renewing acquaintances. That was not enough. I returned in the spring, and again in the summer, and by then I knew that the South had me, sometimes in a comforting embrace, occasionally in its frenzied and unrelenting grip.” In “Deep South,” Theroux drove through some of the poorest sections of the rural South — the Low Country of South Carolina, Alabama’s Black Belt, the Mississippi Delta, and the Arkansas Ozarks. He intentionally avoided the most prosperous areas, usually the cities where there is “wealth and stylishness and ease.” He instead favored small towns, most of which seemed like ghost towns with abandoned houses and boarded up stores. Jobs in these areas are hard to come by due to mechanization, lack of quality education, or industrial shut-downs. While the main reason for the journey was a curiosity about the Southern poor, Theroux found that the good will of southerners “was like an embrace.” People he encountered were kind and generous. Lucille, a woman in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, told Theroux, “Ain’t no strangers here, baby,” before driving miles out of her way to show him the way to a local church. In the Mississippi Delta, Theroux found the people “not just approachable but unpretentious and friendly to strangers, glad to talk, and especially to talk about the past because they were uncertain about the future.” Churches are important to the story because they are the social center of community life. Theroux felt that “poverty is well dressed in churches” and everyone welcomes strangers. He has an ear for dialogue and seemed to relish chance encounters. Conversations in churches, on street corners, in convenience stores, and in small cafes with names like “O Taste and See” are the heart of the book. He found southerners to be talkers who enjoy telling their stories. Theroux visited several gun shows during the course of the year. A sign on an Alabama shop that said JESUS IS LORD — WE BUY AND SELL GUNS connected two of the book's recurring themes. Theroux felt that the gun shows were less about shooting guns and more about the self-esteem of white males who feel defeated and persecuted. Theroux has a novelist’s eye for setting. His descriptive powers are displayed frequently in such passages as, “The cold mist and the gray sky seemed to flatten the Delta and make the road bleaker, the muddy fields beside the long straight road, raised like a levee, the chilly wind from the river that tore leaves from the trees. In its nakedness the Delta had a stark beauty and simplicity.” The book is divided into four parts depicting seasonal visits. Theroux included chapters he called "Interludes" between the seasons. The first is a treatise on the history and use of the N-word. Later, he analyzes Faulkner and other Southern writers. I enjoyed reading about Southern fiction, but felt the interludes were an interruption of the narrative. The relationship between races, both past and present, is a major theme of this book. Theroux was drawn more to the stories of African Americans than rural whites. The characters he met in black churches, cafes, and barber shops were engaging and remarkable. The poverty of both races stunned Theroux, who compared the American South to the poorest areas of Africa and Asia. Theroux spices the book with humorous anecdotes. Describing Southern eateries, he wrote of “a deep tray of okra, as viscous as frog spawn, next to a kettle of sodden collard greens looking like stewed dollar bills.” His experience in Tuscaloosa during a University of Alabama football weekend was of a stranger in a strange land. “Deep South” was an enjoyable road trip through my native land. I learned things about my home state — some embarrassing, but some a source of pride. The South’s greatest strength is the resilience and warmth of its people. I’m not surprised that Paul Theroux felt the pull to return to the South again and again. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed