The Making of a Book

The publication and printing of a book is a complicated process. Shoofly book writer, Carole McKellar, demystifies the process.

The back cover is reserved for favorable comments about the book or a previous book by the same writer. A recommendation by a famous author or media outlet like The New York Times Book Review can make a big difference in a book’s sales. The front flap of the cover has a brief synopsis of the book with information that may also appear in abbreviated form on the back cover. The back flap is reserved for a picture of the author and some biographical information.

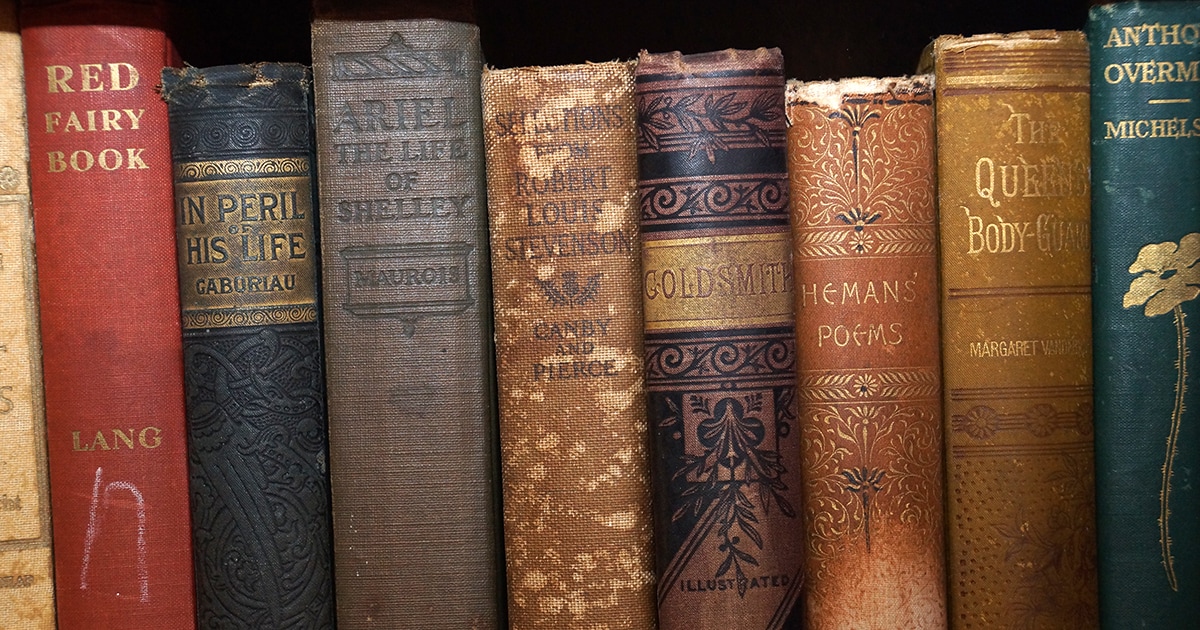

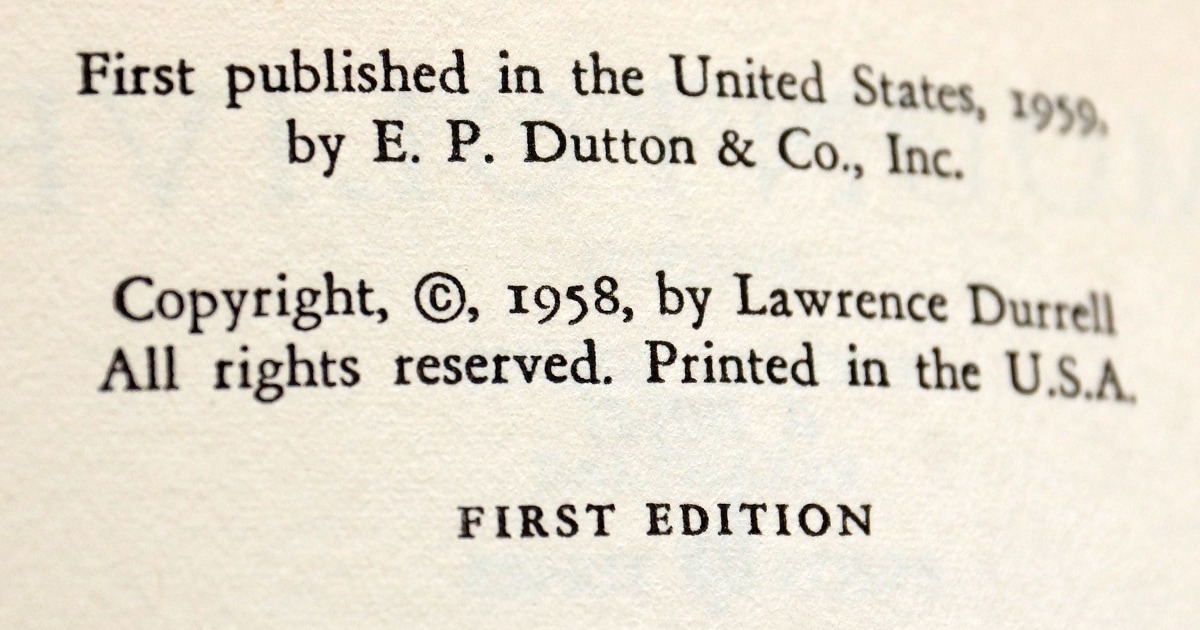

The interior of most books follows a certain order. The end papers, or leaves, are the blank pages in the front and back of a book. Some end pages are plain paper, but many contain graphics such as maps or drawings related to the contents. The half-title page contains only the book’s title followed on the next page by other books by the author. The title page states the author’s and the publisher’s name in addition to the title. The copyright page, on the back of the title page, contains the year the copyright was issued for publication, the publisher’s address, the ISBN (International Standard Book Number), the printing numbers, and the =Library of Congress catalogue information.

Writers apply for a copyright to ensure that their work is protected from theft or unlawful use. The U.S. Copyright Office requires a written application, a filing fee, and a copy of the book. The copyright, once issued, endures for 70 years after the author’s death. After that date, the book becomes part of the public domain. Since the works of Shakespeare and Jane Austen are in the public domain now, we are free to quote them without paying money to their estate. Visual arts, performing arts, and digital content are also eligible for copyright protection. My current favorite book, “Upstream” by Mary Oliver, published by Penguin Press, has a noteworthy motto on the copyright page: Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

The United States authorizes a private agency to issue ISBNs to books to facilitate tracking and distribution. Without an ISBN, books cannot be sold to bookstores or libraries. Once the application is made, a 13 digit ISBN number is issued for each edition of a book including e-books, international editions, and audiobooks. Books published prior to 2007 have 10-digit ISBN numbers while those published later have 13 digits. Books may be registered with the Library of Congress, but registration is only necessary if the book will appear in libraries. Many self-published books aren’t registered. The U.S. Copyright Office is housed within the Library of Congress building in Washington, D.C, so all copyright records are stored there. As I mentioned in a previous column I joined the First Editions Club of Parnassus Books in Nashville. They send me a signed first edition of their choosing each month. Some books have “First Edition” printed on the copyright page, but that’s not true of all first editions. The printing numbers on the bottom of the page are more reliable indicators of edition number. Some numbers are in order 1-10, but frequently there is a nonsensical arrangement of numbers.That really doesn’t matter because you only need look at the lowest number to determine the print edition of your book. In the front of my book, “A Gentleman in Moscow” by Amor Towles, the printing numbers read like this: 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2. I knew that I had a true first edition because of the number 1. Another first edition in my collection, “My Name is Lucy Barton” by Elizabeth Strout, had the numbers arrayed this way: 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1. A friend recently gave me a copy of “Paris to the Moon” by Adam Gopnik which was first published in 2000. I know it was a popular book because the printing numbers were 34 36 38 39 37 35, which meant that I had the 34th edition of the book.

The dedication page allows the author to acknowledge people important to them. Few dedications explain the reason for the dedication and only state names. One of my favorites was the dedication in “Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin,” a collection of essays and stories by humorist, Calvin Trillin. It reads, “My wife, Alice, appears as a character in many of these pieces. Before her death, in 2001, even the pieces that didn’t mention her were written in the hope of making her giggle. This book is dedicated to her memory.”

Acknowledgements may come at the beginning or end of the book and provide a place for the author to thank people who were helpful with the book. They may include family, friends, agents, and/or professional colleagues. The end of the book may contain a glossary, bibliography, index, and/or appendix, but these are usually found only in nonfiction books. An item that often appears in the back of the book is ‘A Note About Type’ which explains the typeface and can be pretentious as in the following from “Paris to the Moon”: The book was set in Fairfield, the first typeface from the hand of the distinguished American artist and engraver Rudolph Ruzicka (1883-1978). In its structure Fairfield displays the sober and sane qualities of the master craftsman whose talent has long been dedicated to clarity. It is this trait that accounts for the trim grace and vigor, the spirited design and sensitive balance, of this original typeface.

The “Big Five” book publishers in the United States contain multiple divisions, or imprints, which can seem like a maze to the average reader. Below are the “Big Five” and some of the imprints within them:

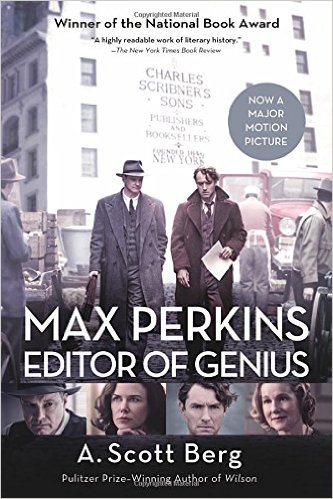

• Hatchette Book Group - Little, Brown, and Company; Orbit • Harper Collins - William Morrow; Avon Books; Broadside Books; Ecco Books; It Books; Newmarket Press • McMillan Publishers - Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Henry Holt and Company; Picador; St. Martin’s Press, • Penguin Random House has nearly 250 imprints and publishing houses. Some of the most well-known are: Random House Publishing Group, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group; Crown Publishing Group; Penguin Group U.S.; Dorling Kindersley (DK) • Simon & Schuster - Scribner; Touchstone; Atheneuum In addition to the big publishing houses, there are small presses that publish writers who may not otherwise get accepted by the larger houses. Many small presses, like Milkweed Editions and McSweeney’s, are nonprofit organizations that publish new and emerging writers. Coffee House Press, another nonprofit press, has published more that 300 books, with over 250 still in print. Coffee House is a favorite of mine because they have the most interesting and artful book covers. Without small presses, talented writers would not receive the opportunity for discovery. More than 300,000 books were published in the United States in 2013, the last year I could find statistics. The information was provided by The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which monitors the number and type of books published per country each year as “an important index of standard of living and education, and of a country’s self-awareness.” Many more books are self-published, but those are not often found in bookstores or libraries. According to the Association of American Publishers, almost $28 billion in revenues were generated by the sales of books in all formats. Unit sales of print books rose 3.3% in 2016 over the previous year, so the book is far from extinct. According to Nielsen BookScan, which tracks about 80% of print sales in the U.S, total print unit sales reached $674 million, marking the third straight year of growth. We read books for many reasons. Whether we read to learn more about the world and our place in it or simply for entertainment, understanding what goes into the making of the book adds to the experience. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed