The Origins of Literacy and Its Significance Today

A coffee-break length trip through 40,000 years of history, to understand how books came into being and influenced Western culture.

- story by Carole McKellar

The Greeks adopted and refined the Phoenician alphabet by adding vowels to existing consonants and choosing to write from left to right. The Greek alphabet is the basis of all western scripts.

During the Greek Classical period between 500 and 323 B.C.E., literacy increased and was believed to be as high as 60 percent for men and 40 percent for women. The philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle promoted intellectual life, and libraries flourished, both public and private. Many works of art of that period portray men and women reading and writing. In the first century, the format of books shifted from scroll to codex, which resemble the books we know today. The first bookbinders were in India, where Hindi scribes bound palm leaves etched with religious texts between two wooden boards using twine. The technique became popular in the Middle East and eastern Asia, and spread to the Romans. There is evidence that many ancient Romans were literate. Early Roman libraries were private, and most consisted of Greek texts seized during war. Julius Caesar planned to open public libraries in Rome, but his assassination cut short his plan. Later emperors realized his dream, and Rome was estimated to have 28 libraries by the end of the fourth century. With the fall of the Roman Empire, libraries closed and literacy declined. The Middle Ages in Europe are generally thought of as a time of intellectual and cultural deterioration. They are pejoratively referred to as the Dark Ages. Literacy during the Middle Ages was primarily the domain of the Church. The introduction of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-fifteenth century allowed the mass production of books and paved the way for the Renaissance, Reformation, and the Age of Enlightenment. Literacy rates in Europe began to rise as books were increasingly printed and distributed.

My interest in the history of literacy and books comes largely from reading “The Swerve: How the World Became Modern” by Stephen Greenblatt. This book, winner of the 2011 National Book Award, opens with the story of the greatest book hunter of the Renaissance, Poggio Bracciolini. In 1417, Bracciolini set out for a distant monastery in search of old manuscripts. His journey predates the Gutenberg press, so books were still written and copied by hand. He was particularly searching for classical texts from Greece and Rome.

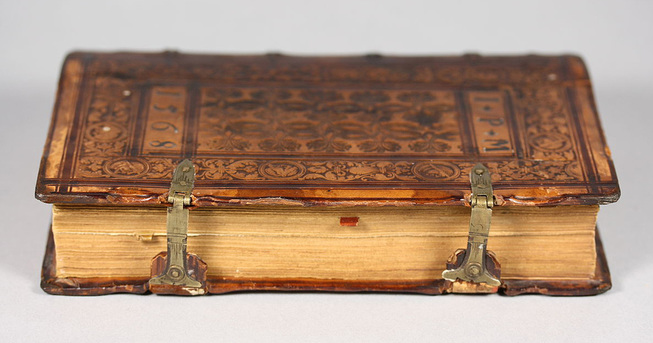

Monasteries were the largest known repositories of manuscripts during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Virtually all monks were literate, and the Benedictine order required reading aloud at meals. Greenblatt states that “Monks became principal readers, librarians, book preservers, and book producers of the Western world.” The description of the work in scriptoria, the workshops where monks copied books, is fascinating. Since paper didn’t come into general use until later, scribes wrote on animal skins. Copying manuscripts could be slow, monotonous work, usually done in silence. Sometimes they wrote in the margins such complaints as, “Thank God, it will soon be dark.” One weary monk wrote, “For Christ’s sake give me a drink.” As Christian literature became available, secular Greek and Latin classics lost favor with the church and were not copied at all. Because writing surfaces were so valuable, new books were copied over classics by Virgil, Ovid, Cicero, Seneca, and Lucretius. Sometimes, the older manuscripts were still decipherable under newer texts. The sole surviving copy of Seneca’s book on friendship was discovered beneath an Old Testament from the sixth century. Bracciolini's greatest discovery was a copy of Lucretius’s epic poem, “On the Nature of Things.” Lucretius wrote the poem in the first century B.C.E. to explain the philosophy of Epicurus to his Roman contemporaries. Epicurus believed that the highest good is pleasure, which he interpreted as freedom from fear and pain. He taught that the way to obtain happiness is to live modestly and limit one’s desires.

Epicurus is key to the development of modern science because of his insistence on empirical evidence rather than blind belief. He was an atomist, believing that the basic constituents of the world are atoms. The Church denounced Epicurus and purposefully mischaracterized his philosophy as the rampant pursuit of pleasure.

“On the Nature of Things” shaped our modern world by influencing Shakespeare, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, and Albert Einstein. Stephen Greenblatt wrote to describe the influence of Lucretius, “There are moments, rare and powerful, in which a writer, long vanished from the face of the earth, seems to stand in your presence and speak to you directly, as if he bore a message meant for you above all others.” Thomas Jefferson shaped our nation in the manner of Lucretius by including in the Declaration of Independence the unalienable rights of citizens to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” In answer to a question about his philosophy of life, Jefferson wrote to a correspondent, “I am an Epicurean.” He owned five copies of “On the Nature of Things” in Latin, along with translations of the poem in English, French, and Italian. Literacy rates in early America rose significantly during the Industrial Revolution as increased production of paper reduced the price of books. The standard of living improved for many Americans, and recreational reading became a popular leisure activity. The National Endowment for the Arts began polling Americans in the 1920s on their recreational reading habits. Reading levels increased from 1920 to 1980, but only 95 million Americans were reading literature at least once per year in 1982. The total population at that time was 231 million, so that means only 41% of Americans read a work of literature annually. From 1982 to 2002, that percentage fell by 10 percent. These statistics are disheartening to me since reading has been my passion since childhood. I am hopeful humans will increasingly feel the urge to communicate through writing. Words are powerful agents providing a window into our shared condition. My life is richer because I love to read. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed