Ecology of a Cracker Childhood

How author Janisse Ray captured the essence of a Southern rural lifestyle in a book that's becoming a classic.

- by Carole McKellar

He was a kind-hearted man who took in injured animals and helped less fortunate neighbors and strangers. He too suffered from mental illness and spent a period of time in the state mental hospital. Ms. Ray’s mother is fondly portrayed as a selfless woman devoted to her family. She worked beside her husband in the junkyard in addition to taking care of the home and children.

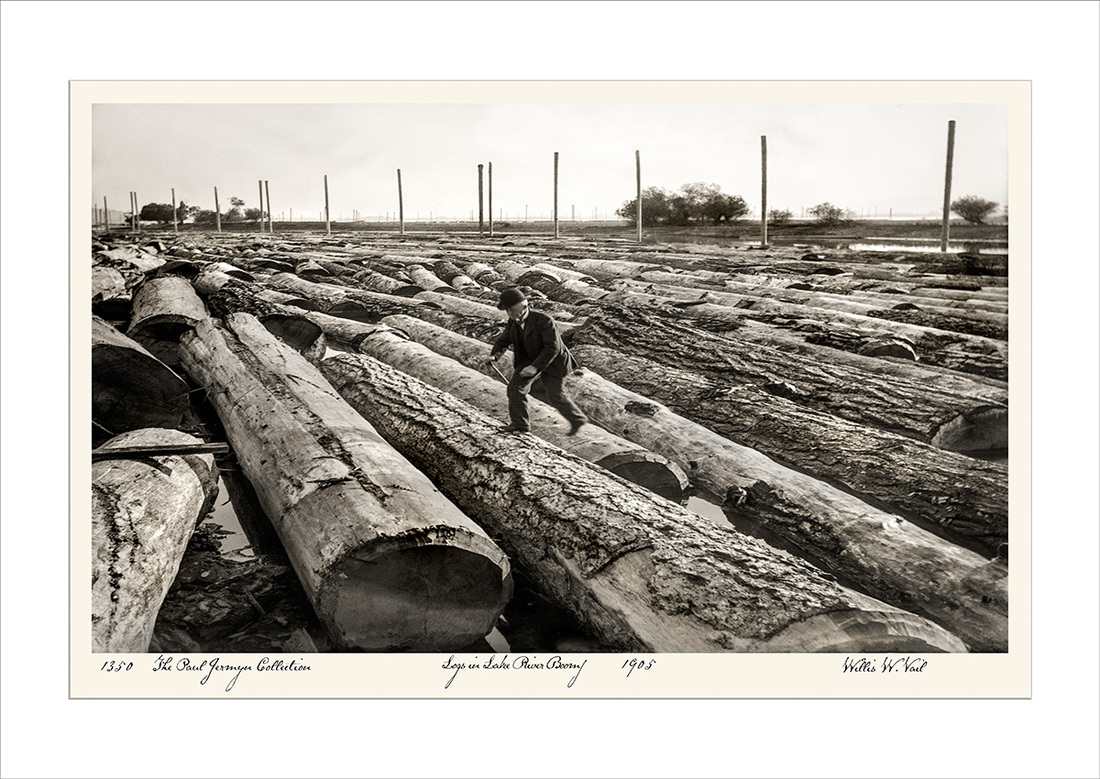

This book as memoir alone would be worth the read. It’s funny and filled with insights into rural southern life. The best of the book, however, lies in the natural history of south Georgia. The longleaf pine forests once covered 85 million acres in the southern United States: from Virginia to Florida, and west past the Mississippi River. Today less than 10,000 acres of virgin longleaf remain, about 200 of which still exist in Mississippi. The longleaf pine trees are spaced far apart and allow sunlight to nurture a wide variety of plant and animal life, most of which are threatened or endangered. Ms. Ray vividly describes what we have, as well as what we have lost.

Chapters titled “Bachman’s Sparrow” and “Indigo Snake” may sound like they came from an old biology textbook, but don’t be fooled. The stories of these species are spiced with anecdotes. Once an indigo, the largest snake in North America, got loose in the house and was found, after several days, wrapped around the freezer coils. Ms. Ray provides such an intimate portrait of our environment that I felt like driving to the nearest forest for a hike. Her pride of place awakens me to the natural beauty that surrounds me. Each time I read this book, I listen more closely to bird songs and delight in the smallest flowers.

The history of the people is as interesting as the landscape. Due to the remoteness of south Georgia, it was an ideal environment for settlers from the borderlands of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. They were clannish herders and farmers accustomed to remote environs. The term ‘Cracker’ refers to poor Southern whites and is possibly derived from words meaning boaster, braggart, liar. Shakespeare wrote, “What cracker is this same that deafes our ears with this abundance of superfluous breath?” Some think the term “cracker” refers to the crack of the whip over oxen or mules. Cracker speech is called Southern highland or Southern midland. Patterns of pronunciation which would be recognizable to any native southerner include ‘young-uns’ for children, ‘Toosdy' for Tuesday, ‘fixin to’ for getting ready to, and ‘honey’ as a term of endearment. Ms. Ray accepts the cracker as kin when she describes her ancestors. My kin lumbered across the landscape like tortoises. Like raccoons we fought and with equal fervor we frolicked. Because we needed room, our towns sat far apart, often thirty miles. Accustomed to poverty, we made use of assets at hand, and we did not think much of prosperity. Like our lives, our speech was slow. We remained a people apart. More than anything else, what happened to the longleaf country speaks for us. These are my people; our legacy is ruination.

v

The book ends with a list of extinct and endangered species of plants and animals. These lists are followed by resources working to assist longleaf pine forests. Readers will finish this book with an intention to appreciate and conserve our natural resources.

Janisse Ray returned home to rural Georgia after college. She earned an MFA in creative writing from the University of Montana. She lives on a family farm in Baxley near where she grew up. She has published five books of literary nonfiction and a collection of nature poetry. Ecology of a Cracker Childhood was her first book. She has contributed to a long list of periodicals, as well as to public radio. I watched a speech she delivered at the 2014 Forum on Ethics & Nature and welled up with emotion when she said: We’re desperate for thinkers, not consumers. We’re desperate for people of courage, people willing to take responsibility for their own actions, willing to live in service to something bigger than their own desires. It seems fitting that creatures of privilege, gifted beings able to use language to pass messages across geographies and generations should speak and act on behalf of those who cannot. Life is unendingly fascinating, unbearably beautiful, and utterly fragile. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed