Rheta Grimsley Johnson believes she was privileged to know a few of the old-school, legendary reporters from 'way back when print ruled journalism. One of them was Mississippi's Bill Minor.

Editor's Note: There's a free showing at the documentary about Bill Minor Rheta refers to in this story on Thursday, April 12, 2018, at the Gulfport Westside Community Center, 4006 8th Street, Gulfport. There's a reception at 5pm and the screening starts at 6pm. It's sponsored by the Historical Society of Gulfport.

In George Wallace’s Montgomery, I grew up on Ray Jenkins’ liberal editorials, the “Ask Andy” science feature and the comics. Especially the comics. I must admit that Brenda Starr might have had more to do with my career choice than Huntley, Brinkley and Ray Jenkins combined.

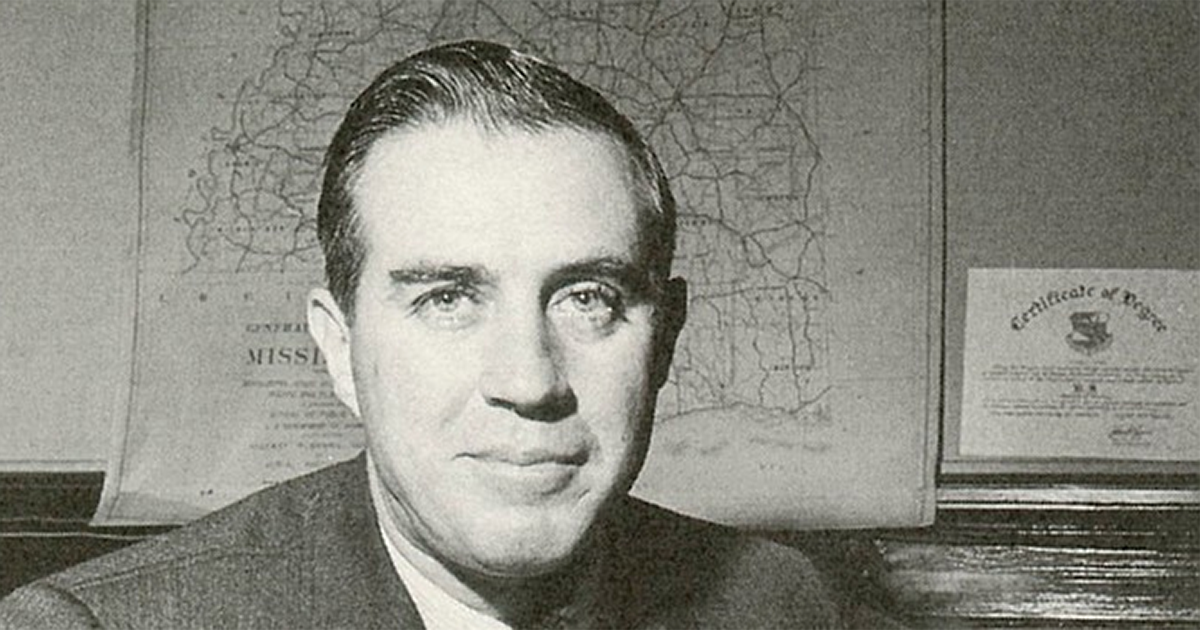

Not to disparage today’s working press – enough unfounded criticism twiddled and Tweeted lately – but I miss the staccato rhythm of the old-fashioned newsroom and the disposition of old school reporters. They never expected to be liked, for one thing, which is probably why they sometimes were idolized. Two things happened recently to satisfy my nostalgic longings for solid, shoe leather journalism out of the Damon Runyon mists. One was the movie “The Post,” which celebrated the guts it took for The Washington Post to publish the Pentagon Papers. I went to the movie not expecting to like Tom Hanks as Ben Bradlee, though I like Tom Hanks. I simply didn’t think he could reach the gravitas bar that Jason Robards set so high in “All the President’s Men.” But Hanks did. He exhibited the sardonic wit and passion for truth that characterizes the best in the trade. If your mother says she loves you, check it out. The second surprise was local, a documentary screening in the Pass Christian library of “Bill Minor, Eyes on Mississippi; The most essential reporter the nation has never heard of.” The room was full. In the film the late, great reporter Bill Minor pretty much narrates his own story, drawn out by the questions of Ellen Ann Fentress, producer and director. Ellen Ann was hired by Bill when for several years he ran a liberal alternative weekly in Jackson, The Capitol Reporter. In all, Louisiana native Bill Minor wrote from Mississippi for 70 years, beginning with Theodore Bilbo’s funeral in 1947. His long career of civil rights reporting began then, writing for The Times Picayune until that New Orleans paper closed its Mississippi bureau. In his last decades, he wrote syndicated columns that did what they could to keep the state’s politicians accountable and honest. Throughout his long reporting career, Bill Minor made enemies, the right enemies, and was threatened and sued and maligned. Our paths crossed in the early 1980s in the Capitol Newsroom in Jackson. Minor was introduced to me as the dean of Mississippi journalists, a title he earned. He also was a really nice guy. As a reporter for Jackson’s struggling United Press International, I quickly learned that Bill was the man to see if you had a question about anything to do with the state’s byzantine politics. He had the key to the vault of institutional knowledge. And he didn’t mind sharing. I last saw Bill in Athens, Ga., at an annual gathering of old civil rights reporters given an ironic lofty title, the Popham Fellowship. It was named for John Popham, a celebrated New York Times reporter who traveled the South to the tune of 50,000 miles a year. His race reporting was the gold standard. I was there to write a column in 1999, the year Popham died. The decision had to be made whether to continue the yearly gathering. It was an emotional, inspirational scene. I’ll never forget the arrival of one of my professional heroes, Bill Emerson, formerly of Newsweek, holding his portable oxygen apparatus in one hand, his whiskey bottle in the other. I can’t remember how the vote went about future meetings, but I will remember till I die roaming the halls of the unremarkable chain hotel amongst the giants of our print trade, including Bill Minor, Claude Sitton, Joe Cumming and the aforementioned Ray Jenkins. The war stories were from the front line. The wit and stamina was legendary. An era was winding down, but not quietly. When Chet Huntley retired from The Huntley-Brinkley Report in 1970, the network gave him a horse because he was moving home to Montana. Huntley lived only four years after retiring. Bill Minor died last year at age 94, still reporting and writing until almost the end, when he became too ill. His last columns were among his best; there was a lot that needed saying. He never left Mississippi or abandoned his hope that race relations and hearts here could change. I am not alone in missing him.

Find out more about Rheta's books at RhetasBooks.com. Rheta's gallery/shop, Faraway Places, is located at 102 West Front Street, Iuka, Mississippi.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed