Crossing paths - and then following - a snake hunting dinner in the woods sparks a contemplation on how humans can relate to other beings in our world.

- by James Inabinet, PhD

The immovables joined in; scale insects covered moist, succulent stems: goldenrod, asters, Joe-Pye weed. Spittlebugs ensconced below; basal leaves pushed back revealed frothy hide-outs. Cocoons were packed snugly inside rolled-up leaves or dangled under them.

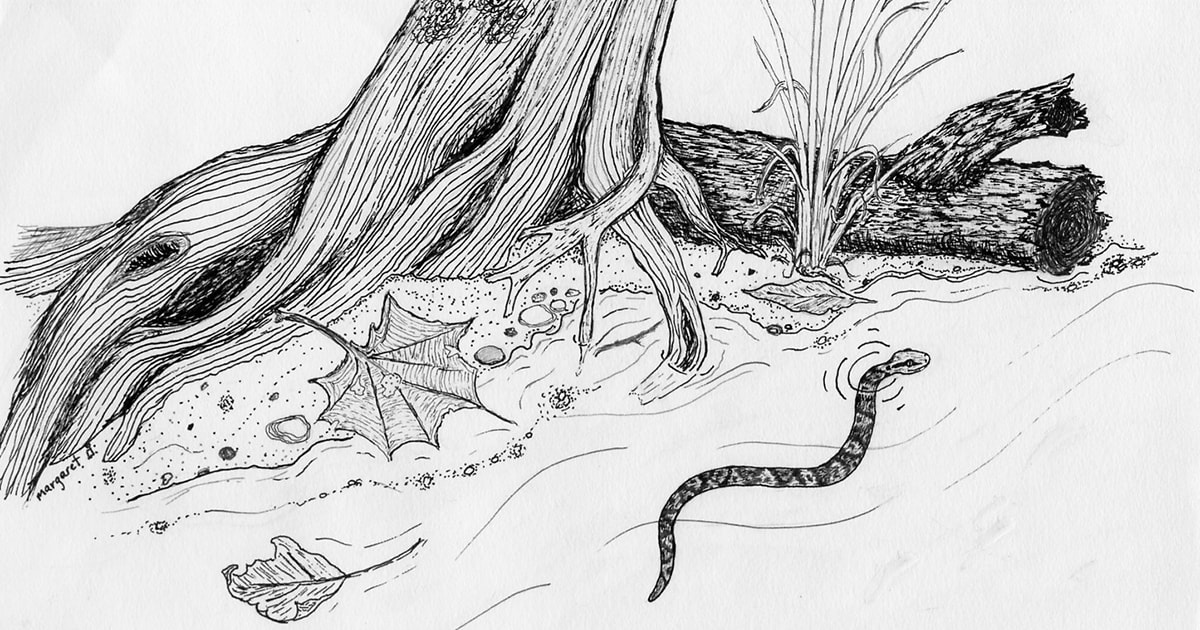

A golden silk spider web blocked the way, a micrathena orb-web right behind it, a spiny-orb weaver web next - signs of late summer. Contorting my body, I went under them. I made my way down the bluff overlooking the creek. Barefoot, I sloshed downstream on the sandy bottom; water just covered my ankles. The roar of cicadas drowned out the rippling water as I approached the confluence of bayou and creek through a tunnel of overhanging limbs and branches. A clearing signaled my approach to the bayou ahead. Movement along the bank next to the trunk of a smilax covered gallberry at the water’s edge revealed a slithering water moccasin. The poisonous snake wended his way into the bayou, hugging the edge. I followed – at a distance. Excited, I watched him slither, weaving back and forth, and then suddenly stop. Motionless except for a wagging tail, he steadied himself, apparently watching something. He remained this way for a long time, several minutes (!), and then struck blindingly fast. A frog jumped to safety, disappearing near the edge while the snake frantically searched. After a minute or so the snake resumed his journey downstream. It occurred to me that this must be the dance of a snake. I followed him, wondering what it might be like to be a snake and slither in the water in this way.

Later, I thought about: “What is it Like to be a Bat?” an essay by the cognitive scientist Thomas Nagel who famously wondered about the consciousness of creatures like bats, forms of consciousness very different from that of humans.

He surmised that there must be “something it is like” to be that organism. In order to determine “what it’s like” to be another being, humans use human points of view by imagining the other to have experiences that are similar to their own. Bats experience the world through sonar, a mode of experience profoundly unlike anything in human experience. Nagel found no reason to believe that batness is like anything “we can experience or imagine.” Concluding his thought experiment, he declared that there is simply no way to know what it is like to be a bat. I presume that knowing what it’s like to be a snake to be no different. Should I forget about the snake? This question cuts to the core of my research of the past 25 years, which is to come to know a forest ecosystem and its inhabitants deeply, even mystically, like a forest monk. The goal: to become a functioning human component within in an ecosystem, a functioning part of its wholeness - to fit in - like our snake or a bat or even a tree for that matter.

If Mr. Nagel remains distant from nature, sitting in his ivory tower armchair watching bats circle a streetlight through a window, he will never know batness and will conclude that no one else can. He could never experience a forest in the way I am seeking.

Because consciousness is subjective, all about me, the experience I have of another being, even a human one, remains difficult to describe. How can someone get to know “what it’s like” for another being? To know “what it’s like” there must be elements of experience where the one is like that of the other. There must be elements of experience we both hold in common. This is what empathy is – feeling the experience of the other. I tear up when you cry because I feel it. Nagel seems to reduce experience to thinking; indeed, he seems to elevate thinking to the order of actual experience wherein what passes for knowledge arises from thinking alone. To look at experience this way is to impose a purely “mental” form of consciousness onto humanity, leaving only a shell of experience. “Thinking” about bats becomes the only way to know about batness at all. You don’t even have to go outside and watch them. Of course, experience itself is always richer than thinking and speaking about it. Thinking about my love, for example, is one thing, but getting a hug from her is so much better. I propose that there are other valid, more experiential, ways of knowing than Nagel’s mental knowing. I propose that “body-knowing” is one of those ways. We have all felt parts of our bodies tightening up or relaxing in the face of profound experience, like the feeling of dread in a place that feels “off.” With body-knowing we know something even though we cannot say what we know - and no amount of thinking can help us to tell. Another way of knowing that I propose is what I call “heart knowing.” It’s a profoundly feeling-oriented, emotional, and empathetic way of knowing, not unlike feeling love for a partner. I have found that you can actually look at and dwell-within another being - even a non-human being - in this manner. If there is any way for humans to experience snakeness, it would seem to require one or both of these other ways of knowing. I am paraphrasing the philosopher Bruno Snell when I add that perhaps a human might never be able to experience a snake or a bat in a “human” way if she did not first experience herself - a human being[!] - in a “snake” or “bat” way. For experience to rise to that level requires more than just thinking about snakes or bats. Following Snell’s ambitious challenge, I have become determined to try a more embodied path to the experience of snakeness and see where that may lead. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed