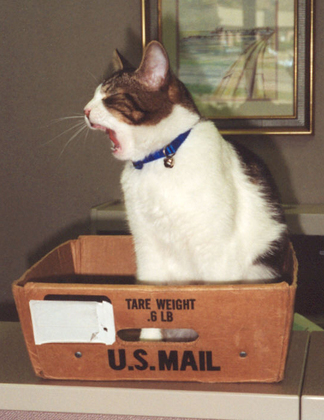

The sugary Southern tradition of baking artful - and delectable - cakes for special occasions is celebrated in this story looking back at some of the town's best bakers.

- story by Denise Jacobs

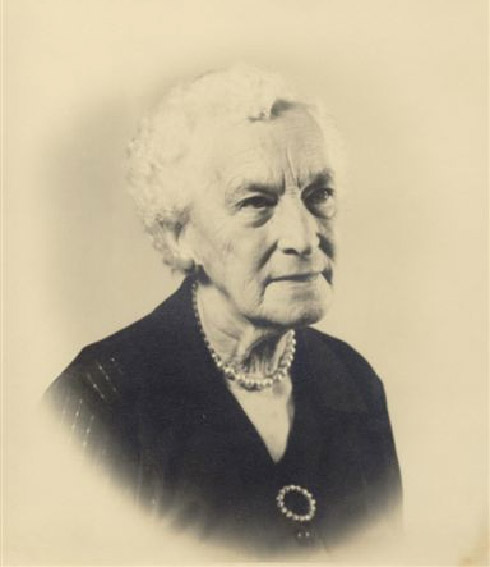

Still, beloved as she was, Ruth Thompson, owner of Ruth’s Cakery in Bay St. Louis, was just one of several cherished cake makers in the Bay St. Louis/Waveland area. And there was Inez Blaize Favre (1900-1983). In the ‘60s, Inez and daughters Udell and Inez—or “Little Inez” as she was known—baked from their house on Felicity Street. Little Inez became Inez Favre Pope. She baked from her home on Highland Drive in her retirement from the late ‘80s until Katrina destroyed the house. Rachel Pope Cross, one of Mrs. Pope’s daughters, remembers her father building a special kitchen on the back of the house to have a proper home bakery. “A delicacy was always in the oven,” Mrs. Cross said, “and friends and neighbors popped in almost every day of the year to pick up their sweet treats.” Mrs. Cross remembers her mother baking over 500 petit fours for the opening of a Biloxi casino. “It fell to me to put dots on sugar cubes to resemble dice.”  One of the red velvet cakes that the family still traditionally serves on Christmas day. Photo courtesy Danita Luttrell One of the red velvet cakes that the family still traditionally serves on Christmas day. Photo courtesy Danita Luttrell

Danita Scianna Luttrell, another of Inez Blaize Favre’s 40+ grandchildren, remembers her Aunt Udell as the master decorator. “Aunt Udell once baked a five-foot tall lighthouse for a Hancock Bank anniversary; I can still see it sitting in the lobby of Hancock Bank down on the beach.”

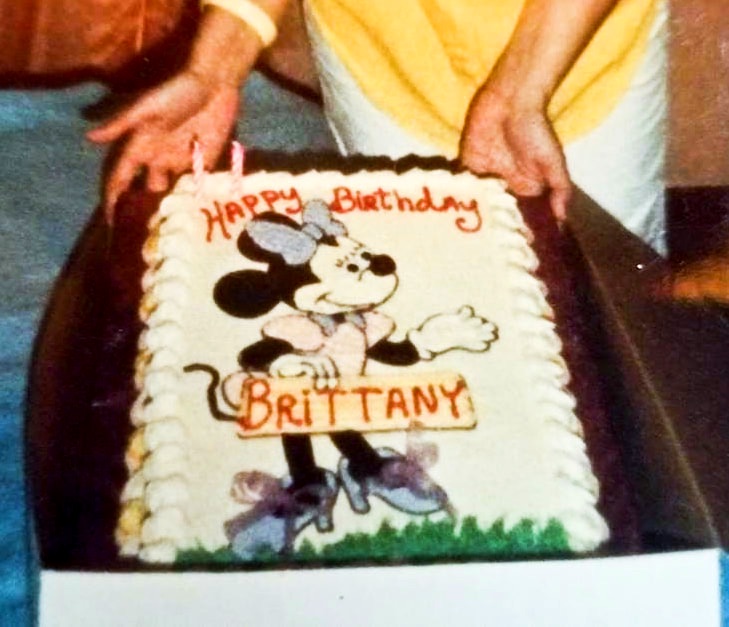

Both Luttrell and Cross remember customers bringing party-themed napkins to Little Inez and Udell. Danita or Rachel would transfer the design onto the cake with a toothpick, and the bakers would fill it in with icing or hollowed-out sugar mold designs. As the girls tell it, all the relatives got in on the act at one point or another by washing mounds of mixing bowls, delivering cakes, or answering the front door. Luttrell remembers her grandmother as an amazing cook and a woman who did everything to perfection. “She would spend more money making something perfect than she made selling it!” Luttrell attributes this to a convent-based education. “She just wanted everything to be beautiful, and she passed down all her talents, from cookery to crewel to cakery, to her children and grandchildren.”

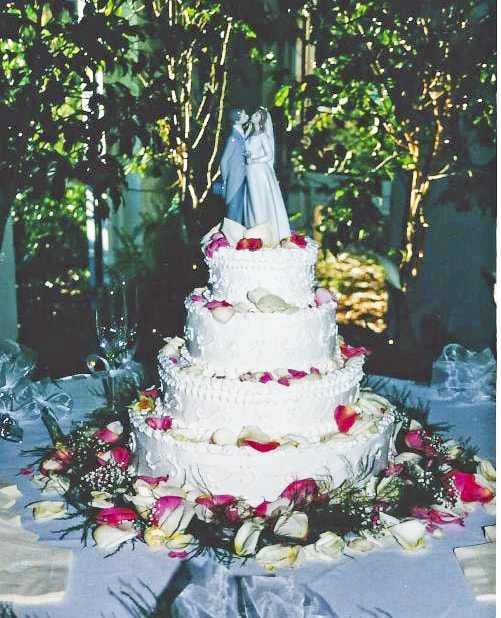

L: wedding cake by Inez Favre Pope for daughter Rachel Cross. Top R: wedding cake for Inez Favre Pope made by Inez Favre. Lower R: cake by Inez Favre Pope for Rachel Cross's daughter. Photos courtesy Rachel Cross

Other cake bakers in the Inez line include Laurin LaFontaine, daughter of one of Inez Blaize Favre’s sons. LaFontaine baked from the mid-1970s through the late ‘90s. Also, Mary Ann Benvenutti, another grandchild, began baking out of her home in the late 1980s. Benvenutti no longer bakes except for special family events. At Christmas, her red velvet cake graces the family dinner table.

Luttrell said that all the women have Inez Blaize Favre’s cake recipes but are sworn to secrecy. “The red velvet cake frosting was not the typical cream cheese type,” she says. “It was almost like a whipped cream, but it’s not whipped cream.”

More cakes by Inez Farve's descendants: Top left - Moana cake by Paul Scianna, top right, graduation cake by Mary Ann Scianna Benvenutti, Car birthday cake (center) by Mary Ann Scianna Benvenutti, lower left - chocolate cake by Laurie Benvenutti, lower right - Berry Chantilly cake by Laurie Benvenutti. Photos courtesy Danita Scianna Luttrell

Women were not the only ones working the cake angle. Other FB commenters mentioned Gregory Morreale, who is said to have made birthday, holiday, and christening cakes that were works of art.

While it is likely that Katrina washed away many photographs of cake-worthy occasions—and there were many—our fondest memories are intact, right down to the aroma of delicate vanilla and warm butter baking, a cake’s soft velvety texture, and the distinctive and delicious taste of childhood—an essence we have never quite been able to replicate.

Special thanks to "You Know You're From the Bay" Facebook page and contributors.

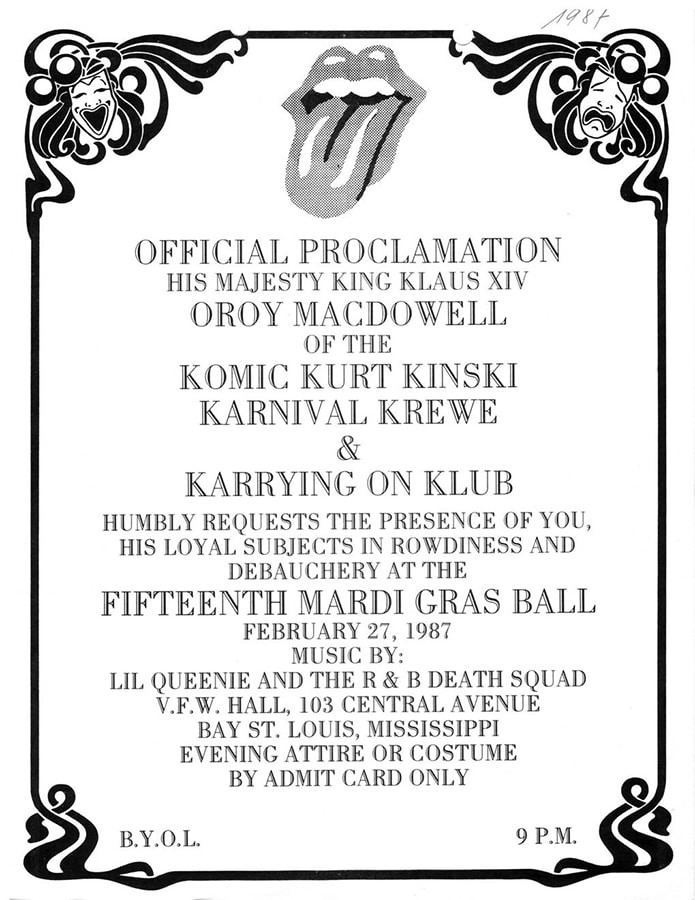

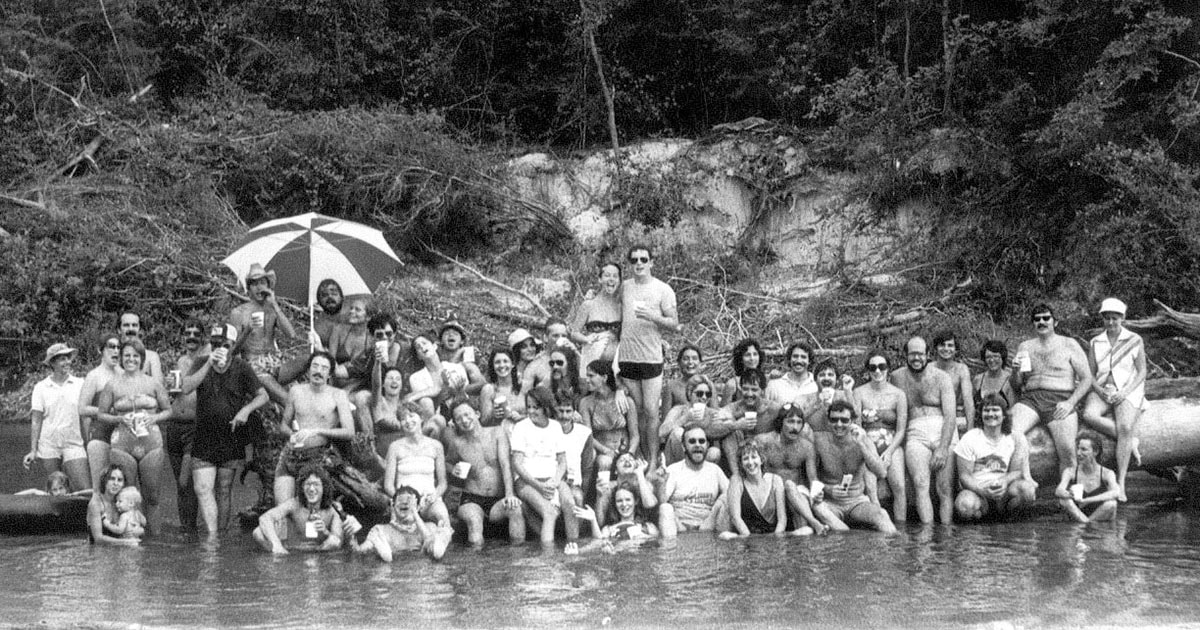

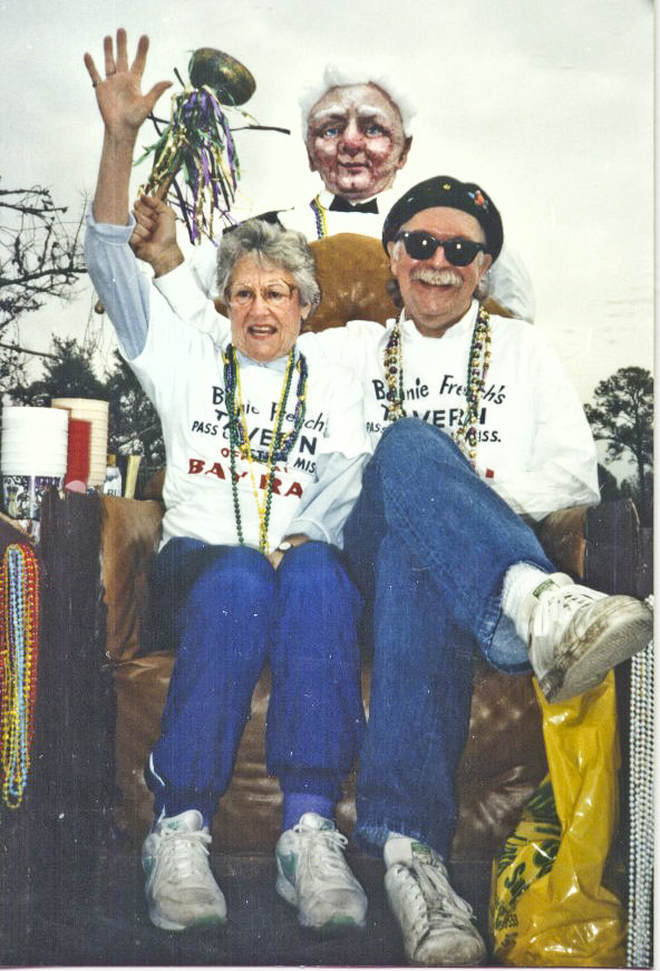

The official name of this rollicking group is the Komic Kurt Kinski Karnival Krewe & Karrying On Klub. Founding member and Bay historian Pat Murphy reveals the club's origins 46 years ago and hints at its future.

- by Pat Murphy, photos courtesy of the Kinski Krewe and Ellis Anderson

On the drive home from Gulfport that night the topic of staying close in the future resurfaced and talk of some type of social club began to swirl. Before arriving back in Bay St. Louis it had already been decided to christen the loosely conceived social organization with the name Kinski.

The idea centered around bringing old friends together at least once or twice per year for social events. While this group was never in need of an excuse to party, they felt that this organization would be a way to make sure it happened. The party, quite simply, had to go on. Over the next several months there were additional meetings held to come up with some operational rules for this loose-knit organization. These meetings were held mostly around parents’ dining room tables and included a few more friends interested in being involved as things progressed.

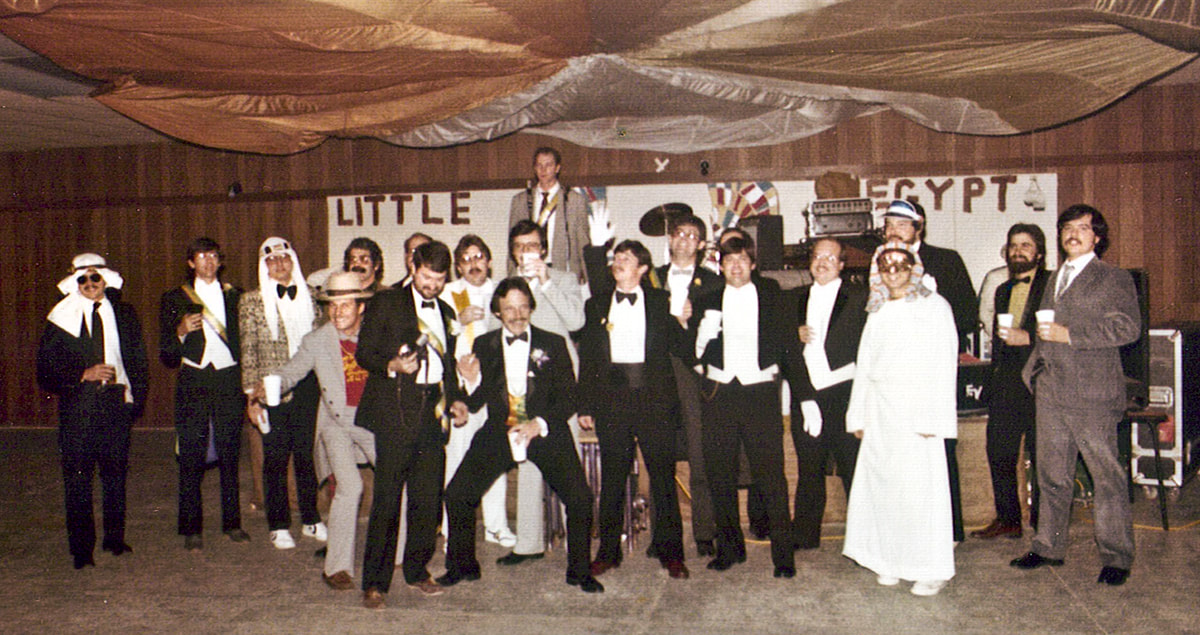

Eventually the original group was christened the "grandfathers" of Kinski. This group of "grandfathers" included Pat Murphy, Wayne Fillingame, Ronnie Genin, Michael P. Larroux, Michael Reeves, Lee J. Hayden, David Adams, Steve Benvenutti, Jimmy Wagner, Mac Hadden, John Heath and Rory MacDowell.

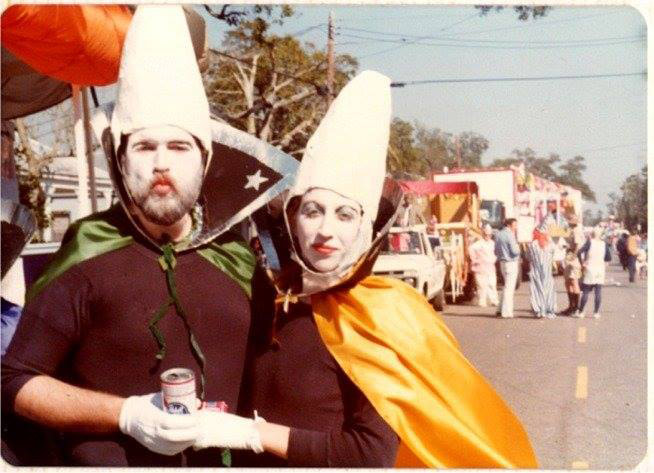

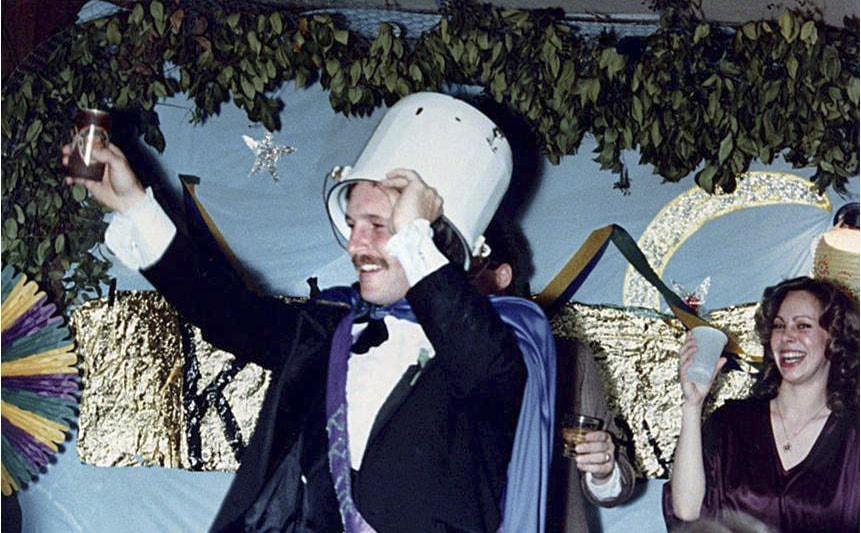

Shortly before the end of 1971, the opportunity arose to ride on a Mardi Gras float in the Pass Christian parade. David Adams' father, Howard already belonged to a group that was participating in this parade every year. Howard offered to sell the Kinski group a dilapidated old float that was laying around behind the florist's greenhouses. For the modest purchase price of $25 Kinski bought the old float from Howard and the Kinski krewe was rolling just like that. Well, not quite, because with Pat Murphy's father pulling the float in a pickup, the tongue of the float broke off in the middle of the 1972 parade and the ride had to be completed in the back of the pickup truck. However, a marvelous time was had by all and a decision was made that this parade was to be the annual event that the Krewe would be centered around. The following year Kinski held its first "Mardi Gras ball" on the Saturday night before the parade at John Heath's parents’ home (without their knowledge while they were out of town). After about two years the ball was moved to the Friday night before the Pass parade. The thinking was that this would give the members a full day and night to recuperate from the ball before riding in the Sunday parade. In a somewhat loose coronation ceremony, Pat Murphy was crowned King Klaus I. The reason for his choice will forever remain a secret within the confines of the Kinski organization and its archives. Each year a new King would be crowned when the court was announced. The King would be decided upon by the King Selection Committee made up of the previous three kings, whose duties also included naming a Queen, Dukes and Maids for the court. After the King's ride in the current year's parade, he would serve as Kaptain of the Krewe, overseeing the business of the organization until the following year. Prospective new members were only brought up for vote before the organization after they had been accepted and approved in a closed meeting of “grandfathers."

In 1979 Kinski began to have live entertainment for their Mardi Gras Ball. Through the years some stellar entertainment played for the Kinski Balls. Marcia Ball played three or four times as well as Anson Funderburgh & The Rockets, Lil' Queenie & The Percolators, A Train, Zachary Richard and John Mooney & Bluesiana to name but a few.

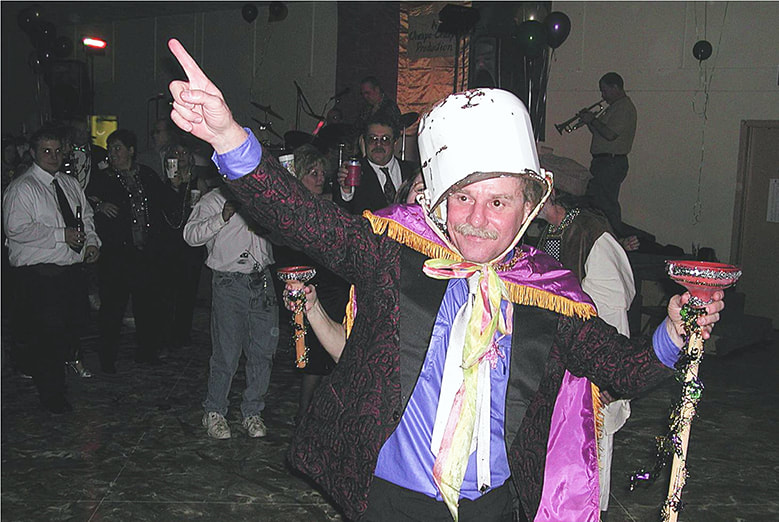

The Kinski balls were created as spoofs on the formal New Orleans Mardi Gras ball's pomp and circumstance. The King’s crown has always been dilapidated old porcelain chamber pot while his scepter was a glittered plumber's helper. Irreverence has always been the Kinski Krewe's central theme. When the organization was founded, no one thought that it would expand beyond a tight-knit circle of close friends. Through the years the circle eventually expanded to include friends of friends, younger brothers, cousins, etc. Members have come and gone. Some of the grandfathers have become inactive and no longer participate in the functions or business of the organization.

Through the years Kinski held other events in addition to the ones at Mardi Gras. Some, like The Basket of Cheer Raffles and The Spring Barbecue, were fundraisers for the group while Cat Island and Wolf River camping trips, crawfish boils and bonfires were simply social gatherings for members and guests

For a number of years the Kinski float was kept in a "den" that the group constructed on property owned by Howard Adams next to his greenhouses in Pass Christian. Later the float was moved to property belonging to the Battalora family's Pass Wholesale Supply. Both of these dens were destroyed in Hurricane Katrina and the float sustained substantial damage but was repaired and continued to roll. Eventually in 2010 the organization rode in the Pass parade for the final time and the float was brought to Waveland and a warehouse on property owned by the Markel family. Several years later in 2014, the group began to ride only in the Waveland St. Patrick's Day parade. Through the years, especially when members were a bit younger, there were some particularly spirited parade rides, especially in the Pass Mardi Gras Parade. The details of these spirited rides shall also remain within the confines of the Kinski Krewe archives. What went on back there stays back there!

Any of the original friends present at those dining room table planning sessions would tell you that it was never envisioned that the organization would continue as long as it has. Never in anyone's wildest dreams was it thought that this club would still be in existence 46 years later!

With the passage of time membership and annual participation has waned. Some of even the youngest in the group are now grandparents and many members, frankly, have other priorities today. There has been much speculation that the 2018 Waveland St. Patrick's Day Parade will have been be Kinski's Last Ride. If you attended this year's parade you saw lots of cabbage, carrots and corn being thrown from the Kinski float as well as the usual spirited irreverence toward everything! After the parade the Krewe threw a "Kinski's Last Ride" Part One celebration in the Longfellow Civic Center at the top of the Bay St. Louis parking garage. "The Garagemahal" as it is affectionately known to many, was a fitting location for the krewe party. Only a limited number of tickets were sold and the affair was a sellout. The Kinski Krewe's first king as well as twenty-first king, Pat Murphy and his band, 'Sippiana Soul played to a packed room full of dancing, partying people.

Many who had enjoyed Kinski's Mardi Gras balls and functions through the years were in attendance on the chance that the event would be sending The Komik Kurt Kinski Karnival Krewe & Karrying On Klub riding off into the sunset. Whether the event was or was not the krewe's last ride remains to be seen but regardless, what a ride it has been! Readers may want to stay tuned for possible Last Rides Part etc., etc.

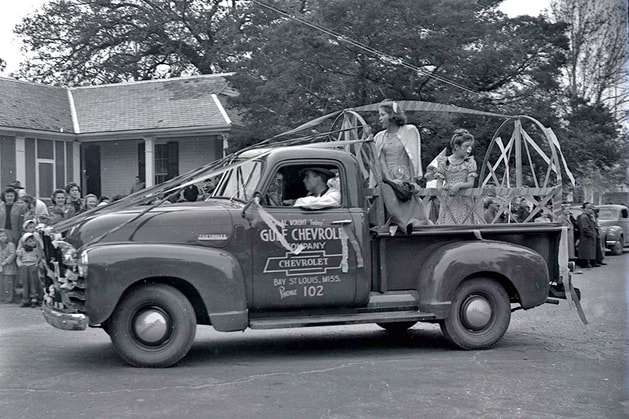

Lisa Monti takes a look back at Mardi Gras in the Bay, remembering parades, throws and the Krewe of Real People's legendary Moss Men.

- photos from the Scafidi collection at the Hancock County Historical Society and courtesy Edward Carver

Every community along the Coast fashioned its own Mardi Gras fun with balls, parades and royalty, going way back to the early 1900s in the case of Biloxi.

Mardi Gras in the Bay, Past & Present

As a kid growing up in Bay St. Louis, Mardi Gras day was the whole Carnival season. That was well before Carnival associations multiplied, their seasonal celebrations proliferated and King cakes were sold at drug stores and grocery stores. Costumes for the most part were homemade, as were Halloween costumes, sometimes becoming interchangable. Accessories were mostly rubber masks that covered the whole face or lipstick and rouge applied in excess. I can remember joining cousins of stairstep ages dressed as cowboys and Indians and gypsies, some wearing scary masks and all holding tight to our bags of throws.

We stood for what seemed like the whole day along a forgotten parade route (maybe on Necaise Avenue?) waiting for the horseback riders, police cars, marching bands and some form of humble floats.

For a time and for some unknown reason, wooden nickels were especially prized throws, though I can’t recall any redemption value. My most memorable throw came courtesy of a long forgotten bakery that provided miniature loaves of sliced bread tossed sparingly to the crowds. To a kid who was captivated by anything shrunk down to a perfect tiny replica, it was a magical possession. Someone recently asked if I remembered when Mardi Gras beads were made of glass before plastic became the favored material. Hard to imagine now that hazard waiting to happen, but so was running behind a mosquito-spraying truck and other experiences done in the name of 1950s fun. Another memorable component of Bay St. Louis Mardi Gras starting in the mid-150s was the marching Moss Men, which Bay resident Larry Lewis recalled in his Good Neighbor profile six years ago. What do Moss Men look like? “Something like a gorilla suit,” said Larry in his Shoofly interview.

I remember the Moss Men dancing in the streets but my most vivid recollection was the terror my very young niece Becky suffered when she first laid eyes on them. To this day, when we talk about anything related to Mardi Gras, the Moss Men always come up. And so do a lot of memories of large family gatherings on Mardi Gras day, homemade costumes, jumping and diving for trinkets and looking down the street for the next truck float or marching band to appear.

We never wanted the parade to end. All because it's Carnival Ti-i-ime Whoa, it's Carnival Time Oh well, it's Carnival Time And everybody's havin' fun Click here for the Shoofly Magazine's historical perspective on coast Mardi Gras celebrations. Click here to read about former Moss Man Larry Lewis in the Shoofly archives.

Although shoofly decks were nearly extinct on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, three women decide that Bay St. Louis should be home to at least one: how the town's current shoofly came into being.

- story by Ellis Anderson

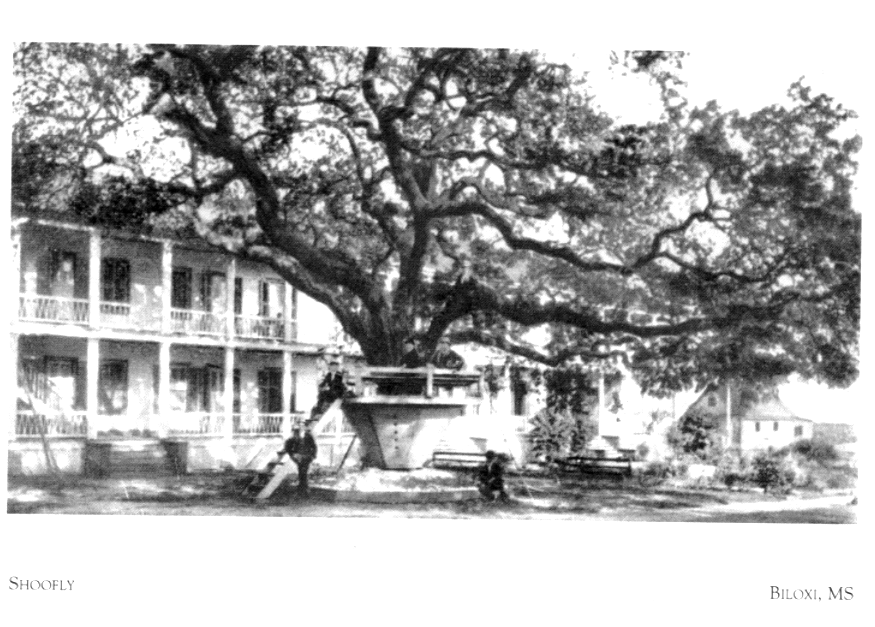

By the late 1900s, only a few remained on the entire coast. An iconic one stood in the Biloxi Green. Another had survived somewhere in Ocean Springs. Bay St. Louis had none.

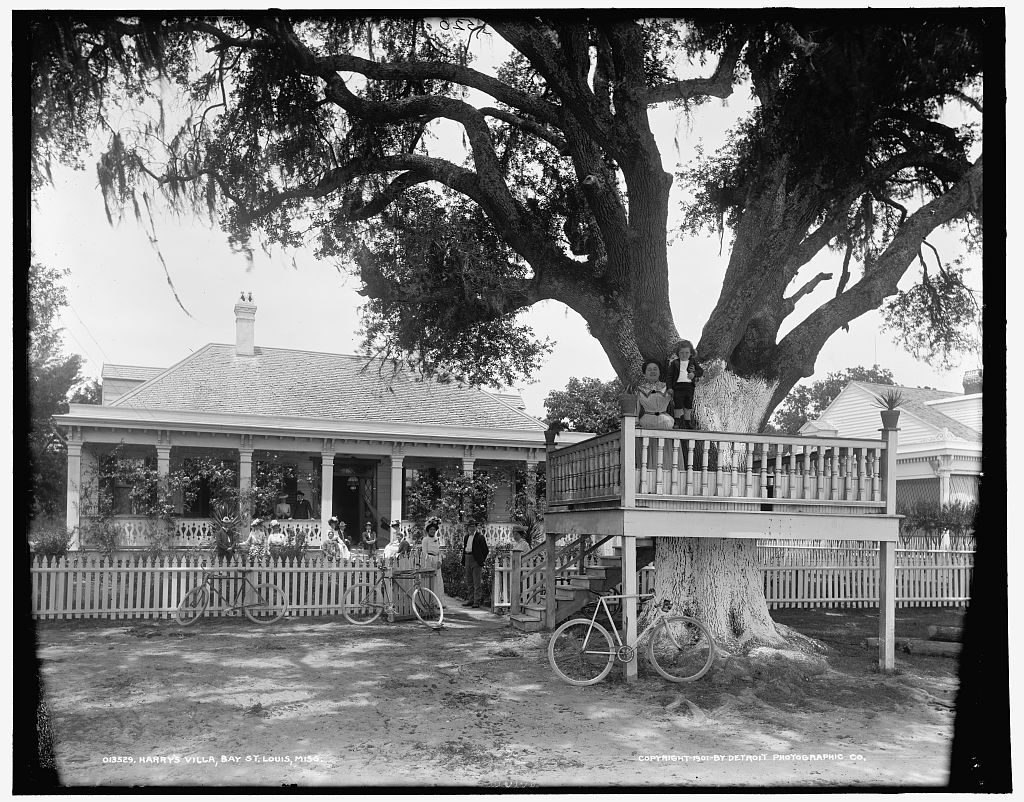

What had survived though are two astonishing photographic images preserved in the Library of Congress. Both were taken in the Bay around 1900 by a photographer named William Henry Jackson. Jackson took them for the Detroit Photographic Company, a national postcard enterprise. The images show different views of the same Beach Boulevard shoofly. Jackson took one picture from the road looking toward the house and called it “Harry’s Villa” after the first name of the owner. The shoofly is in the foreground, an elegant wood home behind it. A woman stands on the shoofly, while a boy is perched in the fork of the tree trunk, temporarily taller than the adult.

Jackson shot the other perspective from the porch of the house, pointing his camera toward the water. In the picket-fenced yard are Harry’s wife, Mrs. Boyle, their daughter and a grandchild. Several people stand on the deck of the shoofly. Judging by their hats and dress clothes, they’re probably guests at the Boyle’s boarding house.

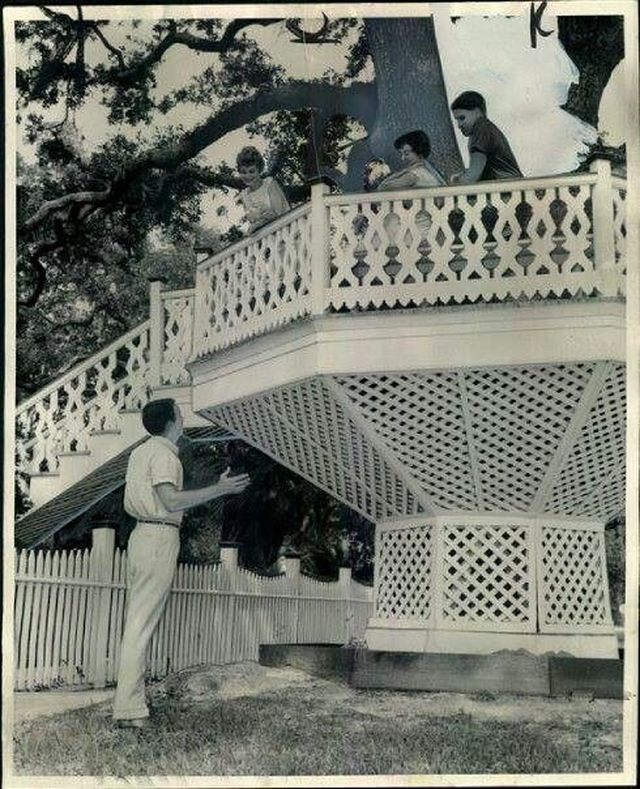

Yet, despite its historic shoofly stardom, Bay St. Louis remained shoofly-less until 1989 or ’90, when three Bay residents – Mike Cuevas, Zita Waller and Pat Cucullu – visited Ocean Springs for a home tour. Waller and Cucullu have passed away, and Cuevas tells the story. One of the featured houses – Cuevas doesn’t remember exactly where - had a shoofly in the yard. The three were enchanted and took photos.

Cuevas, who worked for the city, asked Mayor Eddie Favre, who was serving his first term, if building a city shoofly in the Bay was a possibility. “He said the same thing he always did when I asked him for something,” recalls Cuevas. “He said, ‘Sure, you raise the money and we can do it.’” The live oak on the property of the historic City Hall on Second Street was chosen to host the project. Cuevas says that later Farve himself found the funding to add to donations that came in. Architect Kevin Fitzpatrick and engineer Wayne Peterson volunteered their professional services, making the project a possibility. In the end, the cost for the shoofly construction was around $20,000, with the public works department providing the labor.

Fitzpatrick, an architect well-versed in historic preservation (he currently serves as chair on the city’s Historic Preservation Commission), remembers the project well. As a college student before Camille, he often traveled the coast, driving between Tulane University in New Orleans and his parents’ home in Florida.

“Back then, it seemed like the coast was covered with them (shooflies),” Fitzpatrick said. “I’d always admired them, so I was able to design the Bay’s pretty much from memory.” Fitzpatrick designed the railings to match the ones on the historic city hall, while engineer Wayne Peterson worked on the structural engineering. Fitzpatrick said he remembers joking with the engineer after seeing the support system Peterson devised. “I told him that we’d be able to park a locomotive on that thing,” Fitzpatrick said. “It seemed way over the top. But Wayne believed that people would assemble on the Shoofly for weddings and events, so it had to be extremely strong. And he was right.” Peterson’s other concern was for the tree itself. The deck had to be self-supporting so it wouldn’t harm the ancient oak and it had to allow plenty of room for the tree to grow. According to Peterson, “The base at the ground is close to the base of the tree, with the platform cantilevering out at the top. In addition, the structure had to be designed to support a lot of ‘weighty politicians.’ I understand that it has successfully supported a lot of those over the years.” “It’s still something when I see it,” says Peterson. “My hope is that it gives people a little of the pleasure that growing up and living on the coast has given to me.”

Of course, the Shoofly Magazine is named after the iconic town landmark - a perfect place for elevated community conversation!

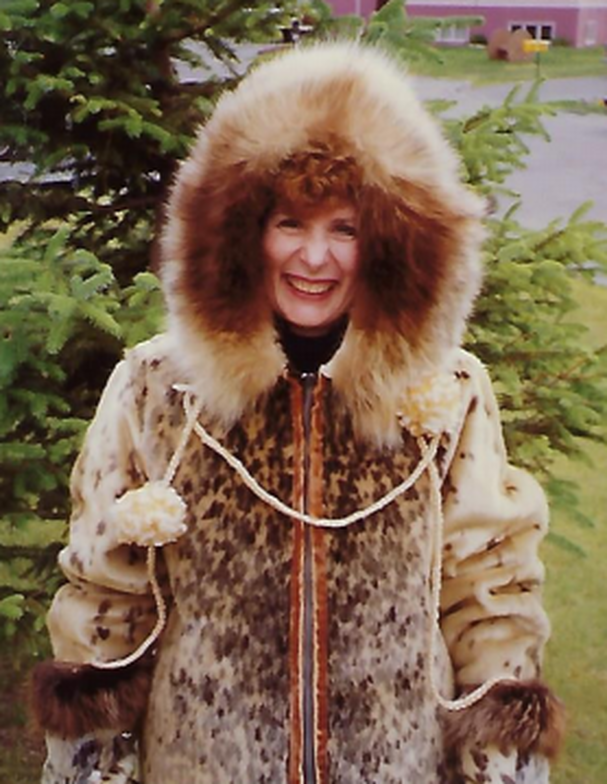

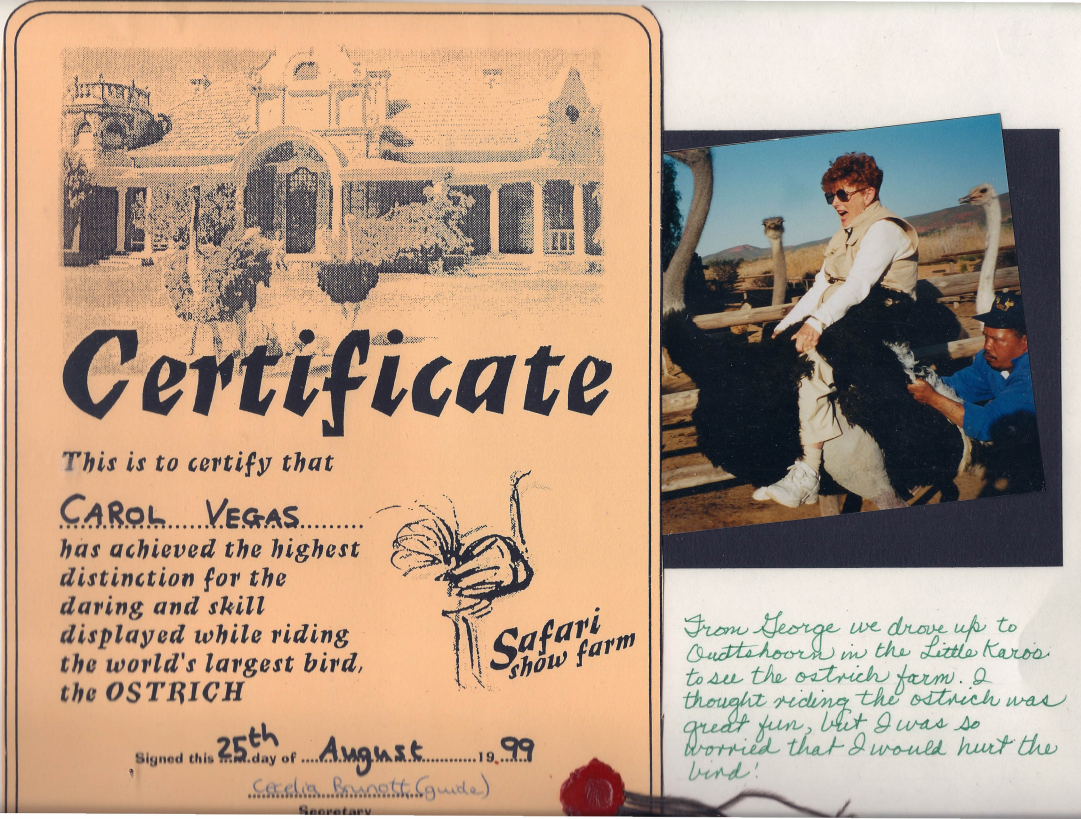

Legacy of Lovely: Carol Vegas

The park surrounding the historic Bay St. Louis City Hall and the shoofly oak is named after a woman who left a lasting legacy of loveliness.

- story by LB Kovac, photos courtesy Holly Vegas

She did missionary work with primitive Indians in the rainforest. She slowed down a little to have four kids. All of this under, as Holly puts it, “a hail of gunfire:” Guatemala was in the middle ofa brutal civil war, one that would only be settled a little before Carol Vegas’ death. But the war didn’t stop her; Carol Vegas did what needed to be done.

Carol Vegas in 1938: she came by her love of hats at a young age Carol Vegas in 1938: she came by her love of hats at a young age

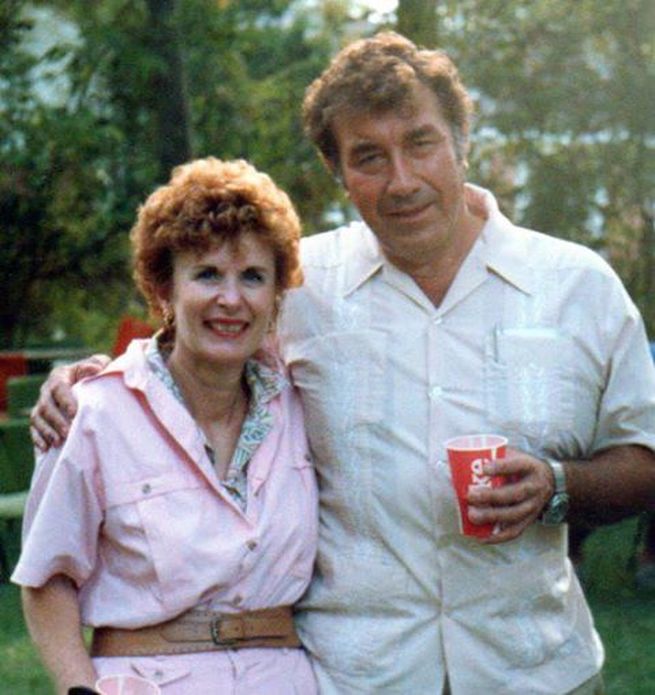

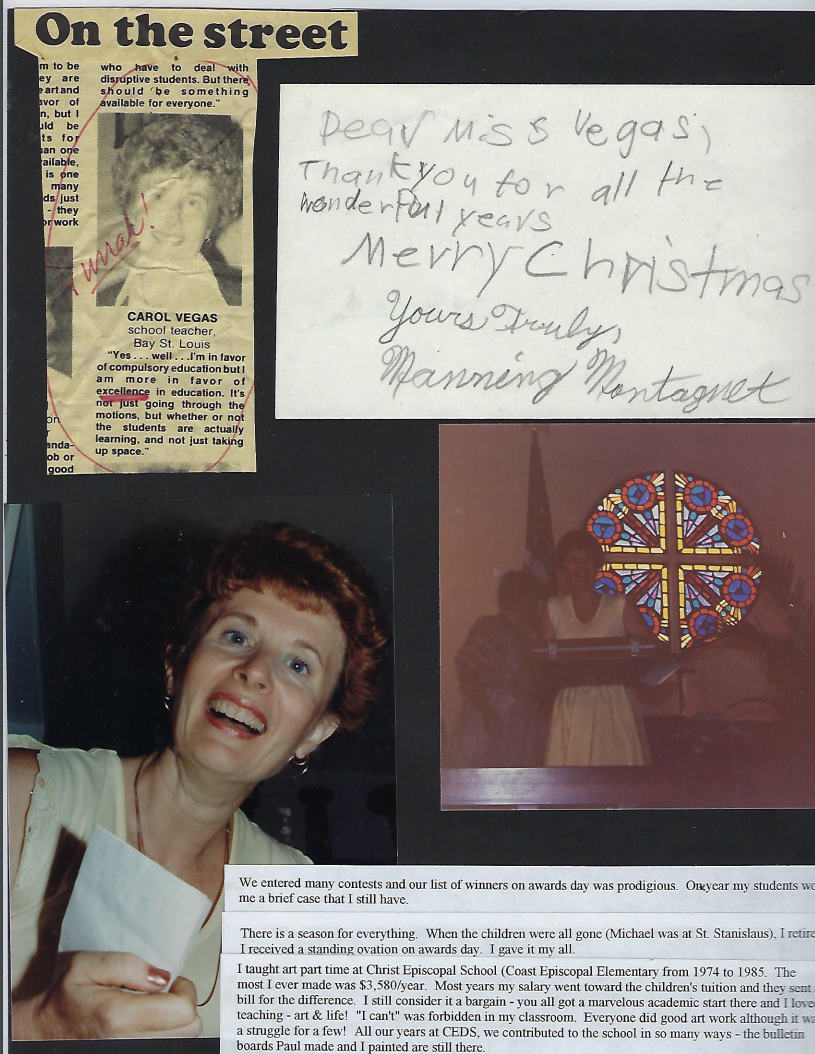

When she finally got to Bay St. Louis, she didn’t settle down into the role of quintessential Southern housewife so prevalent in the 1960s. The only hallmark of that image she retained was her penchant for hats. Holly says, “She loved her hats; any time there was a significant event, she would find a way to wear a hat.” She was 5’3” and had fire-licked hair out of a bottle, something women at the time just didn’t do.

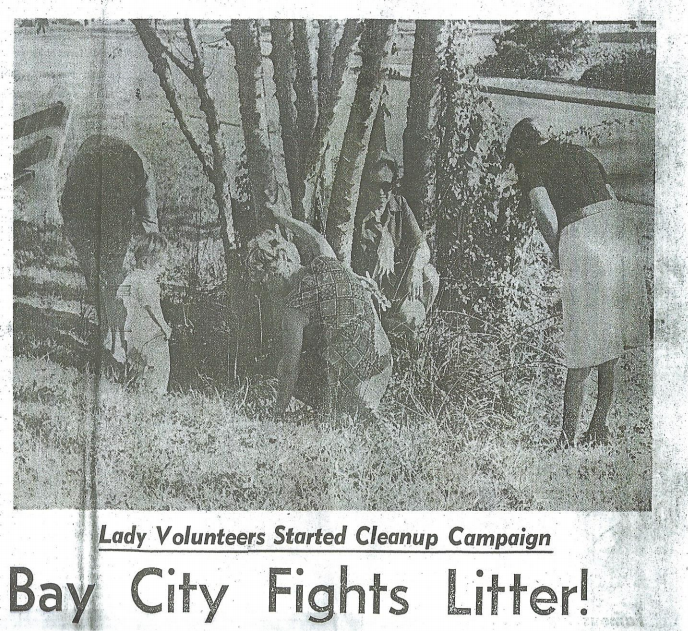

And this beautification business that Carol Vegas is now so famous for? Holly says it all started because of trash. “She was infuriated by people throwing their junk out,” she says. And, once again, she did what needed to be done. “She wanted the new place she called home to be a better place.” Carol and three other ladies organized a group of kids who would pick up trash in the mornings and on the weekends. “That’s what I remember about growing up: always being dragged around to pick up litter.” “She would never not do the right thing,” says Holly, and this strong sense of ethics is something the daughter feels she inherited from her mother. “And, if there was something to be done – a party or whatever – she would do it to the nth degree.”

It’s around this time that she met Ellis Cuevas, long-time publisher and editor of the Sea Coast Echo. The two “fell in a good friendship,” as Cuevas puts it, and, over the year’s served on many committees, boards, and task forces together. Cuevas can attest to Carol Vegas’ long list of accomplishments. “It was a hell of a journey [working with her],” he says.

“[Her] biggest project was anti-litter.” Of course, where this litter was mattered little to Carol Vegas, or Cuevas. Together they served on the Bay St. Louis Beautification Committee, the Hancock County Beautification Committee and the Marine Debris Taskforce, where they helped on numerous projects that made the neighborhoods, roads and beaches less trash-filled and more beautiful. Independent of Cuevas, Carol Vegas also served on several highway landscaping committees and city beautification projects. She’s credited with designing the Tree of Life at the Harriet Center and the rose window at Christ Episcopal Church. For her efforts beautifying the Gulfport area, Carol Vegas was awarded medals, titles, plaques and other awards too numerous to even list.

In the last years of her life, when she’d “retired” from public work, Carol Vegas did not let up. Holly shares, “Her ritual every morning was to call all of these people and just listen to them. She was a kind of therapist… That’s what caught me off guard [at her funeral] – how many people she emotionally supported… And she did it all out of this sense of purpose.”

Picking up litter certainly isn’t the glamorous side of beautification – not like designing gardens or arranging ornamental flowers – but it is important and necessary. Carol Vegas made a career out of it. If you ever see the sunlight coming over the old City Hall, casting long shadows over the swing sets or the wildflowers, think that it wouldn’t be that pristine or beautiful if it weren’t for someone seeing a piece of litter and deciding something needed to be done about it Just a few months prior to its opening, the park formerly known as City Park was a mess. No one needs reminding that Hurricane Katrina hit the area hard, and a lot was lost. But Carol Vegas Park was one of the first things in the area people came together to clean up and rebuild it. More than 500 volunteers and residents worked to clean up debris, lay the foundation and add the equipment donated by KaBoom! And, in Carol Vegas’ name, the area was left a little brighter. 1985: A Church Fair Becomes Crab Fest

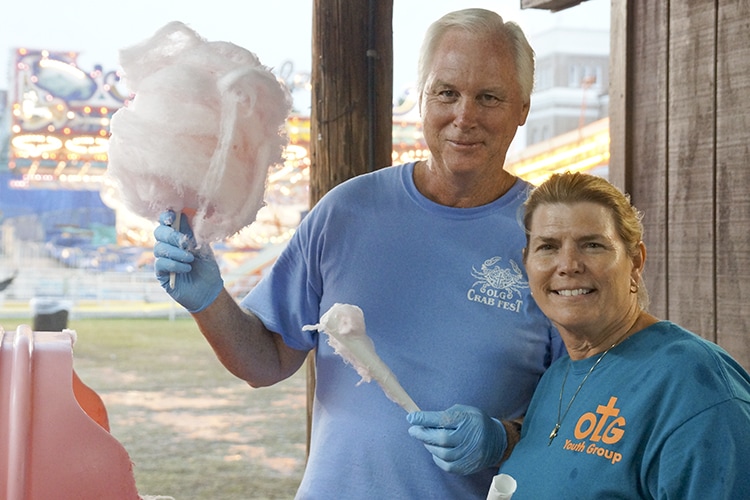

"Crab Lady" Pam Metzler and other Crab Fest veterans share the history and traditions of this favorite coast festival.

- story by Lisa Monti and Tricia Donham McAlvain, photographs by Ellis Anderson

“We don’t charge for admission so it’s impossible to know how many people come in, but it’s thousands. At night sometimes you can hardly walk,” said longtime Crab Fest chairperson Pam Metzler.

Church fairs were a big part of growing up here, and many volunteers are carrying on a family tradition. “All the local church families worked the fair,” said Metzler. “My mom worked the cake booth.” The first few years of the festival, it was held on property that celebrity clarinetist, Pete Fountain owned (near the foot of the bridge where the Chapel Hill neighborhood is now). Pat Murphy remembers playing there with his wife Candy, guitarist John Bezou and drummer Jerry L’Enfant. Metzler says the festival was moved to the church/school grounds because the shade from the live oaks gave some relief from the mid-summer heat, yet still allowed for breezes from the gulf. This year’s Crab Fest will be the 20th year Metzler has served as chairperson. In 1997, Pam, who was Hancock County's circuit clerk at the time, was approached by Father Pete Mocker, who asked if she'd take on the enormous job of chairing the event. After consulting with her family, who promised to help, she took on the job, becoming the first woman to do so. Now she's retired from the county, but not the Crab Fest. She and the other dedicated volunteers return year after year to keep the pieces and parts of this three day festival rocking along. It’s hard work, in the heat, but they enjoy it. “Everybody always has a wonderful time. A lot of volunteers aren’t even church members, they’re just members of the community or members of other churches, other denominations,” Metzler said. “Because it’s so fun.”

Just a few of the regular volunteers

(editor's note: these Shoofly Magazine photographs were taken before 2017 and a few of the folks below have passed away since then).

Metzler and others shift into Crab Fest mode in January, and a few even set up camp on the fair grounds ahead of the opening. “Six months ahead of time, they start getting ready to prepare food,” Metzler said.

Laura Piazza Griffith (editor's update: Laura passed away in 2019) makes 600 pounds of crab stuffed potatoes. Others boil 7,000 crabs and 3,500 pounds of shrimp. Some fry the seafood and make the gumbo and other items. Kevin Haas and Mike Gibbens have been boiling the crabs and shrimp since the beginning days of the festival. "Starting 15 years ago, we got it down to a science,” said Haas. “We boil the crabs and shrimp separately in big pots with baskets in water. Then we cool the crabs or shrimp in water with seasoning, in what we call "charge pots" and then they are ready to eat.” The Monti family has been involved in the Crab Fest since before day one. “The Monti brothers, Bill and Joe, had the original idea for the Fourth of July fair and carnival,” said Metzler. “They said let’s do a crab festival, it’s the Gulf Coast and there was no one doing one at the time.” The late Gene Monti (“The Sweetest Man in Town”), his wife Mary Alice and his sister Lydia Favre were long time volunteers. Gene was well known as the cotton candy man and he also handmade cast nets that were raffled off. The husband of Monti’s niece carries on the traditional of knitting crab nets that are raffled. “It’s a great, great festival and so much fun. We laugh and we work and we’re tired, I truly love it,” Metzler said. “I tell people you can’t quit the Crab Fest, you have to die to get out,” Metzler jokes. “We’ll be 80 and still be out there boiling crabs.” And for those who make it to closing, there’s even a fun tradition. “We get the band to play the second line and the die-hard volunteers who have stayed to the end dance all around the pavilion waving napkins," says Metzler. "When we throw our napkins down that means Crab Fest is officially over for the year." "Then, we go soak our feet in the [soft drink] cooler with the leftover ice," she says, laughing. The Legendary (and Non-existent) Captain Longbeard

Pirate Day is the Bay is centered around a pirate named Captain Longbeard, but it turns out that he's a shipmate of the fictional Jack Sparrow.

- story and photos by Ellis Anderson

The Krewe has created a mock-history based on the real deal, a story that’s much more colorful that the rather dry history and features a fictional character called Captain Longbeard (each year played by the current king of the Krewe).

Captain Longbeard is now taking on legendary status. John Rosetti, 2017 president of the KOTMS, says he found it hilarious last year when one television station talked about Longbeard as if he were a real historical figure. “He was just something I drew up on a napkin,” says Rosetti, laughing as he recalls how the character was created. The actual historical event at the center of all this merriment happened in 1814 as a precursor to the more famous “Battle of New Orleans.” The Sea Horse was an American schooner that single-handedly took on the British fleet in a “David versus Goliath” encounter, right in front of the Bay St. Louis shoreline. While the little ship was hopelessly out-manned, it managed to delay British forces, giving Andrew Jackson (who was commanding American forces in New Orleans) more desperately needed time to organize that city’s defense and keep control of the Mississippi River out of British hands. Since the event occurred two centuries ago, accounts of the battle vary, but as local historian Charles Gray often says, “history is lies agreed upon.” The most riveting part of Gray’s version occurred when an older woman on crutches shouted to shore-side onlookers of the battle “Will no one fire a shot in the defense of our country?” She then grabbed a lit cigar being smoked by Bay St. Louis Mayor Toulme and lighted the fuse to a cannon, which fired into the midst of the British attackers. Mayhem ensued.

The battle’s connection to pirates is very tenuous, but the Battle of the Bay did take place in 1814 when buccaneer types abounded in the area. In fact, legend has it that the real legendary pirate, Jean Lafitte, had a house on the beach near the BSL/Waveland line.

And historians do agree that a few weeks after the Bay St. Louis battle, Lafitte and his band of ruffians fought alongside Andrew Jackson in New Orleans to repel the British invaders – a battle that probably would have been lost without the pirates’ help. But don’t let the facts stop the fun. Captain Longbeard – this year played by MKOTS king Al Copeland – will be storming the town on the weekend of May 19th and 20th. If you’d like to read more, details of the actual battle can be found here on the Krewe of Seahorse’s website. Also, Charles Gray suggests reading Paul La Violette’s 2003 book, Sink or Be Sunk! The Naval Battle in the Mississippi Sound That Preceded the Battle of New Orleans. It’s available at Bay Books on Main Street. Discovered History

A Hancock County database aims to assist in search for enslaved ancestors — excerpts from the introduction to the slave database, a work in progress on historian Russ Guerin’s website.

— By Russ Guerin, with intro by Ana Balka

We encourage you to browse Russ’s entire site. The years that Russ has put into research and writing on Hancock County and Gulf Coast history are reflected in the dozens of pages and thousands of words you will find there. Thank you, Russ, for letting us reprint these selections on the slave database.

I. Slave Data Base – Hancock County, MS

by Russell Guerin

Over recent years, I have had a number of inquiries, both in person and online, by folks looking into their Hancock County forebears. Even though my website is not a genealogical oriented source, it has been fruitful to a number of people whose ancestry includes African-American lineages.

One example of success involved a professor at an eastern university who was able to identify her ancestor as having been one of the “servants” at the Sea Song plantation in Waveland, described in my article a couple of years ago. The mention of names has sometimes been included in those articles where slaves are listed in official documents such as land deeds and probate records. In the case of the example above, the source of names was in family letters. Making identification difficult is the fact that slaves were referred to by first names only, as though they had never been part of families. It is commonly known that former slaves, when freed, often took the names of their previous masters. It may be that tracing of ancestors could be substantially helped by knowing the last names of those who had held others in bondage. (Click here to read more and to see the database in-progress).

Slave Data Base – some observations

by Russell Guerin

Almost all slave mentions studied from original documents in Hancock County, Mississippi show only one name — neither first nor last, simply one. The acquisition of last names by freed slaves was an important post Civil War transition. Whether there was an official program of renaming, or whether and when choices were made and recorded, has not been found. Still, it can be observed that the changes took form in patterns.

The source of information for these observations was for the most part the census of 1870, and to a lesser degree, the census of 1880. While a presumption is made that those listed under “Race” are former slaves, it should be considered that there were no longer any identifications as “Free Persons of Color.” Names and descriptions assembled from early slave-day documents such as estate inventories and property transfers were then compared to census data. Surnames Chosen after Emancipation As was common in other areas, in Hancock County a common choice was to assume the name of a former owner. However, it has not always been possible to relate the chosen surname to a former slave’s own owner. Some of the more prominent slave owner/dealers were the following: Carver, Cowand, Johnson, Favre Amaker, Claiborne, DeBlieux, Fayard, Casanova, Cuevas, Johnston, Benois, Mitchell, Bell, Poitevent, Mitchell, Russ, Carroll, Otis, Daniels, Brown, Jordan, Dawsey, Peterson, Peters, Henry, Nicaise, Wheat, Wingate, Farr, Bird, Varnado. Another obvious choice for some was to take the name of an important person, such as Jefferson, Jackson, Washington. Even the name Lee shows up in Hancock, though it is doubtful that the former commander of the Army of Northern Virginia was the person in mind. There were also odd names, chosen perhaps for their potential symbolism: Worship, Mars, Whig, King, Christmas, President, and Absalom. A pattern that arose to the surprise of this writer but seems to stand up to investigation was the choice of transforming the former slave name to that of the surname, which then allowed for an assumption of a new first name. Those slave names that became last names that can be clearly demonstrated were Sam, Isaac, John, Moses, Monday, Martha, and Henry. Historic Tour of Old Town

Wend your way through Old Town taking in the Bay's historic gems with the paper - or the mobile - version of this popular tour.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson

The original wooden Depot was built in 1876, and was destroyed by fire approximately 50 years later. The present structure was built in 1929, in Spanish Mission style. A park surrounds the Depot and includes a walking track, a duck pond and picnic tables, all under shade provided by large live oaks. The fanciful building served as a set for the 1965 movie, “This Property is Condemned,” starring Natalie Wood and Robert Redford, directed by Sydney Pollack. It was one of Redford’s first films.

Just a block away, at 398 Blaize Avenue, stands the real star of the movie, the “Starr Boarding House.” Most of the film centered around this building, but its star status didn’t prevent it from languishing for years and nearly being demolished. Saved in a dramatic last-minute community effort, the building was meticulously restored with the help of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History post-Katrina. It now serves as home to the Bay St. Louis Little Theatre.

Some other personal favorites on the tour:

Tercentenary Park, which memorializes Bienville’s entrance into the Bay of St. Louis over 300 years ago. The park is located on the point of highest elevation on the Gulf of Mexico - 31 feet. It’s the official starting point of the tour, but one can begin anywhere and enjoy the stroll. The Palm House, close to the Depot (217 Union Street), is a West Indies Planter style house built in the 1880s. For many years, it was the home of Joan Seal, the wife of a circuit judge. Mrs. Seal was recognized as a generous philanthropist in this area and so devoted to her dogs that she left provisions for them in her will.

The Piernas House, at the corner of South Toulme and St. John Street, is a side gallery cottage, and former home Louis Piernas, a free black man who was a community leader. In 1889, he received a presidential appointment to serve as postmaster of Bay St. Louis. Piernas, who lived to be 98, also served as chairman of the Hancock County Republican Party for 65 years, even traveling to Chicago for the 1882 convention.

The Weinburg House and Cobbler’s Cottage - 112 South Second Street - was originally constructed by John Himes in 1868. Based on its hip or gable-on-hip roof and undercut gallery, the larger house is identified as a “Biloxi Cottage.” It’s now home to the popular Mockingbird Café. Next door, the eye-catching – and very diminutive – cottage served as the workshop of cobbler Manuel Maurigi for many years. One can imagine the delight of his ghost at seeing the cottage now, filled with artwork as the home of Smith & Lens Gallery.

The Railroad Street Houses are located at 125-129 Railroad Street. These Queen Anne Revival style homes were built by Eugene Ray, an African-American who was a respected local contractor and undertaker. The largest of the three houses was home to the beloved bishop who was born in Bay St. Louis, Leo Fahey.

100 Men Hall, located at 303 Union Street, isn’t on the tour’s official route, but is suggested as an “Off the Beaten Trail” destination. The blue and white clapboard building was built in 1922, and was such an important and popular site for music - and socializing - that it is included on the official Mississippi Blues Trail.

St. Rose de Lima Catholic Church (301 South Necaise Avenue) is a short hike from the 100 Men Hall and is also highlighted by the tour. The church was built in the mid-1920s, by local craftsman Joseph Labat. The “Christ in the Oak” mural behind the altar is a nationally recognized work of art.

The Old Town Biking/Walking Tour was conceptualized, written and photographed in 2008 by Ellis Anderson. Historian Charles Gray contributed stories of local lore (especially the more colorful bits) and helped with research, while graphic designer Jenny Bell of Adlib designed the brochure. Live Oak Alliance, a non-profit headed by Marcie Baria, backed the project and brought the tour to first fruition.

The first printings were completed with the help of a grant from the Mississippi Gulf Coast National Heritage Area and funding from Live Oak and other local sponsors. Currently, printings are coordinated by the Hancock County Tourism Development Bureau and are sponsored by the Bureau, the Hancock County Historical Society and Ellis Anderson Media. Myrna Greene, executive director of the Bureau, calls the tour brochure “the most effective and popular tool we have to introduce people to Bay St. Louis.” It’s updated periodically and is scheduled for a fourth reprinting in March 2017. Perhaps the most memorable part of the tour however, is the people you’ll meet along the way. When you’re taking the tour, expect the warm and friendly nature of the neighbors along the way to make the experience even more memorable. I even had someone ask me for directions to the Hancock County Historical Society. I gave them the guide. You wouldn’t want to miss Kate Lobrano’s house on Cue Street!

Note: Since several of the buildings on the tour route are private residences, the tour brochure specifies on the opening page: “While we encourage exploring our public treasures here, please respect the privacy of our residential listings.”

The Spectacular Mardi Gras Mind of Carter Church

A small Mardi Gras museum in the historic Bay St. Louis depot features samplings of the extraordinary costumes designed by the iconic Carter Church. Celebrate Nereids 50th anniversary by visiting!

- by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson

Ornate satin gowns, capes and breeches, headdresses, and beads are de rigueur at balls and on floats. During our recent visit to the Mardi Gras Museum, Susan Duffy, the Depot’s concierge, explained that a queen’s costume can take as many as 400 hours to create. Each crystal jewel is individually pasted onto the gowns and other pieces of the royal ensemble.

The dresses are special creations, fitted to each individual participant. Both royals wear high collars - iced with sparkling silver decorations, crystals jewels, and flowing with white or dyed ostrich feathers. The high collars are a modern design, typical for contemporary queens and kings. The Nereids Kings’ and attending dukes’ costumes are equally elaborate and consist of tunics, short capes, and knee-length breeches. The King’s crown is smaller than the Queen’s and is decorated with the special motif of the year - and white ostrich feathers. The other costumes in the collection were also created by Carter Church. After a brief period of rest following Mardi Gras, Church begins to design ceremonial regalia for the next Carnival season. Krewes in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama reach out to him for their costuming needs. In most cases, the theme for the next year is determined by a krewe; then, it becomes Church’s duty to create sparkling ceremonial clothing to illustrate the chosen motif. Fanciful designs, such as an alligator and swamp scene on a queen’s gown or Aztec-themed costumes intertwined with satin snakes are typical of Church’s detailed designs. Church’s original design drawings are situated in front of each display at the Mardi Gras Museum. His drawings are beautiful in their own right. His many years of experience have gained him noteworthy acclaim in the fashion industry.

In a small exhibit slightly off the main hall of the museum is the costume Carter Church wore as King of Nereids in 2013. Church said that serving as King of a the famous all-women krewe was the highlight of his life.

Also included in the display is a Queen’s collar in the Medici style. The late 16th Century fashion consists of a rigid fan worn upright behind the head of a female wearer, not the large, towering form seen in modern queens’ regalia. The Medici style collar is decorated with crystals and silver decorations. Costs for such finery can vary from nominal amounts to thousands of dollars. In the case of Kings and Queens of some krewes, the costumes will be worn the following year during the presentation ceremonies at the balls when the previous year’s royalty is presented to the new King and Queen.

One of the museums’ volunteers is Martha Franks, who has a special connection to it. Mrs. Franks is Carter Church’s sister. When the number of visitors rises during the busy seasons at the museum, or the staff is otherwise occupied, Mrs. Franks gracefully steps in and guides the guests through the display. According to Duffy, she is well versed on the royal wear and the creation of each special costume.

The museum’s collection of elaborate costumes dotted with crystals and feathers give out-of-town visitors an up-close view of the Mardi Gras celebration. According to Duffy, approximately 800 to 1,000 people stop by the Depot each month. Each visitor is welcomed with his or her own set of Mardi Gras beads. The Mission-style train depot is also home to the Hancock County Tourism Development Bureau, headed by Myrna Green. The historic building was restored after Hurricane Katrina. The depot and the grounds surrounding it are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and it is a Mississippi Landmark Property. The museum is located at 1928 Depot Way in Bay St. Louis and is open every day of the year except Sundays, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day. The second floor of the Depot is home to the nationally acclaimed folk artist Alice Moseley's museum. A Legacy of Joy

The Krewe of Nereids celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2017 and membership for some has become a treasured family tradition.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Ellis Anderson, Ana Balka and courtesy of Nereids

The krewe has 134 members; 101 are casting members who participate in the ball and parade. Of the 134 members, the krewe has 50 members who are legacy members. The genealogy of families with generations of membership is complicated, but altogether fun.

Several legacy members said that while it is an honor to be named queen, it's even better is to see one’s own children, grandchildren, sisters, and nieces join and participate in the traditions of the Krewe of Nereids. One example of family heritage in Nereids is the Ladner/Turcotte/Roche family, represented by 19 members. Four generations have served in a variety of roles at the annual ball including pages, maids, and queens. One member explained, “Most of the children are involved as they are growing up. Whether it is dancing in the balls, helping their moms with beads, floats, whatever is needed. So becoming a member is just the next natural step.”

In some social organizations, legacies (aka female family members) are given preference for membership. The Krewe of Nereids’ approach is different: applicants with family members in the krewe are reviewed for membership without favoritism.

A requirement for membership is for the woman to be 21 years old or older. Despite the age limit for membership, young people (children and grandchildren) can serve as pages. The Krewe of Nereids is a multicultural, multi-faith organization. It's not a secret how to become a member of the Krewe of Nereids. First, you complete an application, which you can get from a member of the krewe or from the website and have three members verify that you would be a good member. The krewe board will meet to approve or disapprove the request and vote whether to accept or not. Heritage is not limited to the women and girls of this all-female krewe. According to many members, “We could not do it all without the men.” Husbands, sons, cousins, and grandsons participate by preparing floats, participating in the parades, and attending the lavish balls. They also serve as pages, dukes, and kings for the ball and parade. The king is selected by the captain. Several members spoke of the exhilarating nature of parading: waving at the crowd, throwing beads, singing to the music and, altogether, enjoying the experience! “The parade is exciting," said one Nereid. "[I would] never miss the parade. I would have to be dying!”

Past Nereids parades, photos by Ana Balka and Ellis Anderson

Each year during the parade, float riders throw signature beads, cups, and doubloons. Other throws include cups, posters, doubloons, and koosies related to the theme of the year. Stuffed animals and toys are also tossed out to a delighted crowd. Since 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the Krewe of Nereids, members are working on a special throw to celebrate that milestone.

February is the apex of activities for the Krewe of Nereids: the 50th annual ball will be held on Saturday, February 4, and the krewe will parade on Sunday, February 19 at noon. For additional information on the parade route or to purchase tickets to the ball, the tableau, or after-party, go to the Krewe of Nereids website. With the hard work of the krewe members and their families, both the 50th anniversary parade and ball will be magic! Mississippi Heritage Trust

With Lolly Barnes at the helm, this organization is making enormous strides in the state, helping save our historic buildings for future generations.

- by Rebecca Orfila, photos courtesy MHT and Ellis Anderson

As in the case of Mary Helen Schaeffer’s home, MHT calls on volunteer professionals and other resources to help secure historical properties under threat of loss. In coordination with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, plus a number of state and federal funding agencies and available private and public funds, MHT strives to serve the state of Mississippi.

History and preservation are important to the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Many of the Coast’s historical landmarks and structures have been pounded by hurricanes and gales, resulting in historical homes left twisted and pushed off their foundations. Some damaged structures were abandoned. Lolly Barnes serves as Executive Director of MHT, which is supported by the MHT Board of Directors led by Doyce Deas of Tupelo. Along with Director of Programs Amber Lombardo and Special Projects Coordinator Erica Speed, Barnes is an active leader and contributor to the identification and preservation of historical properties and at-risk structures. Her team also develops educational materials and holds workshops throughout the state for preservationists, architectural historians, and historians. In recognition of her work with the Mississippi Heritage Trust, Lolly was recently awarded the Presidential Citation from John Beard, President of the Mississippi Chapter of American Institute of Architects (AIA). The award is given at the discretion of the AIA-MS President for exceptional work performed on behalf of AIA-MS.

The Mississippi Heritage Trust was established in 1992 as a non-profit organization. Its mission to save and renew places meaningful to Mississippians is accomplished by education, advocacy, and preservation. In a recent interview, Barnes said, “Informing the public of historical properties and their contribution for defining the sense of community” is an important component of MHT’s longstanding missions.

One of MHT’s biennial activities is the naming of the Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites in Mississippi. Barnes said, “The goal of the program is to raise awareness about the many threats facing our rich architectural heritage.” The first site identified on the Save My Place Program was the Biloxi Lighthouse, which was damaged by Katrina’s storm surge and high winds. It took over a year and $400K $400,000 to restore the structural and electrical components, plus the lookout windows. The restoration of the tower was complete and ready for tours in March of 2010.

In 2015, the 1929 Jourdan River School (formerly the Kiln Colored School) was added to the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites. The Top Ten Most Endangered Historic Sites is a program that serves to identify and champion the protection and restoration of important historical sites.

Other schools on the MHT list of recognition and preservation projects include the Randolph School in Pass Christian, West Pascagoula’s Colored School, 33rd Avenue School in Gulfport, and the old Pascagoula High School.

Also on the list is the Valena C. Jones Colored School in Bay St. Louis which is situated on a high point in town and received little damage during Hurricane Katrina. The Hancock County Emergency Operations adopted the structure as a base of activity. With input from MHT, the restoration of the gymnasium included new windows, reinforcement of masonry walls, and replacement of the classic curved roof of the gymnasium. Later, a Boys and Girls Club was established in the gymnasium.

The Heritage Award of Excellence for Restoration/Rehabilitation has recognized the Hancock Bank Building (Pass Christian), 513 E. Scenic Drive (Pass Christian), Beauvoir (Biloxi), Bay St. Louis City Hall, Dantzler-Fabacher-Franke House (Gulfport), and 139 Seal Avenue (Biloxi), and 123 Seal Avenue (Pass Christian), to name a few.

When asked what 2017 might bring for MHT, Barnes responded, “We will celebrate the 25th anniversary of MHT and another year of being a successful non-profit organization.” Important to the continuing life of the Trust, efforts will be made to “build out our capabilities as an organization” and to continue fundraising efforts.

On Saturday, November 19, MHT will present “Delta Drive-In” at the Burrus House in Benoit, Miss. The event celebrates the 60th anniversary of the filming of the cult classic “Baby Doll." There will be an open house to explore the exemplary restoration of the antebellum Burras House from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., followed by a screening of the film. Tickets are $75 a person, with proceeds benefiting the Burrus Foundation and the Mississippi Heritage Trust. See the Facebook event page for more details. Are you interested in attending the Delta Drive-in event or becoming a member of the Mississippi Heritage Trust? Contact MHT by email at [email protected] or phone at (601) 354-0200. St. Mary Cemetery

Walk through one of the loveliest resting places in Hancock County with Becky Orfila, who introduces some town residents who are long passed from this earth.

- by Rebecca Orfila

With evidence remaining of storms, winds, and time, this peaceful graveyard is the resting place for approximately 2,000 individuals. The cemetery is owned and managed by Our Lady of the Gulf Church in Bay St. Louis. A simple walk through this cemetery brings one closer to the resting places of many families from Hancock County.

Several graves predate the 1872 dedication date. Blanche Teresa Scull died in 1852. The 15-year-old was the daughter of Hewes Charles Scull and his wife, Louisiana Philipana Scull (they were cousins) of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Blanche was attending St. Joseph’s Open School when she died. She is buried in St. Mary Cemetery, in the northeast corner of the Sisters of St. Joseph plot. (Plot: N10-26: see how to find the gravesite by number at the end of this article). Nicolas Caron/Carron was buried in St. Mary in 1859. Nicolas was married to Ursule Justine Saucier, the daughter Phillipe Pierre Saucier, Sr. In the 1850 U.S. Census, it was reported that Caron had properties valued at $9,000, making him a member of the top five wealthiest men in Shieldsboro (N09-01). The first burials following the cemetery dedication in 1872 by Father Henry LeDuc — with the blessings of Bishop Richard Oliver Gerow, Diocese of Natchez — were for Sisters Estelle Astier (1872), St. Peter Elder (1874), Ellienna Alloid (1878), and Louise Felicity Robinson (1880). These initial interments established a dedicated plot for the Sisters of St. Joseph (N10-03). In the Bishop’s report, “Catholicism in Mississippi,” published in 1939, the Bishop refers to St. Mary Cemetery in several places.

The death and burials of the Very Reverend Florimon J. Blanc and the Very Reverend Aloise van Waeberghe are recorded in Bishop Gerow’s report. The Bishop’s statement identifies that Blanc and van Waeberghe were interred in a vault at “Calvary,” which was an underground vault and aboveground monument located at the intersection of the east/west trending cemetery road and the first right-side roadway.

One undated historical plat map has survived and a circular area is identified in handwritten script as Calvary. The circumference of Calvary measured 36 feet in circumference or 23 ft in diameter. No aboveground evidence of the Calvary remains and it is unknown whether an underground vault and burials exist. It is likely that the Calvary was destroyed by one of the major storms in the area. A familiar name in Bay St. Louis, Clement Robert Bontemp, was interred at St. Mary in 1918 following his death from battle wounds received at Chateau-Thierry, France (N02-15). His military grave record shows he was born Nov. 6, 1893, Bay St. Louis, MS and served in the sixth regiment of the U. S. Marines during World War II. The American Legion Post 139 in Bay St. Louis was founded in 1923 and named after Bontemp. The Italian Society Mausoleum has one of the largest funerary structures in St. Mary Cemetery. The Society vault is Italianate in style and marks a section dedicated to the entombments and interments of society members.

A member of the engineering and maintenance crew of the Delta Steamship Line ship, the SS Del Sud, Funston Mauffray died on April 27, 1959 (S07-23d). The ship was only 11 days out of port at the time of his death. Two weeks later, Mauffray was buried at sea (South Pacific). Mauffray was 39 at the time of his death and was a 1921 graduate of St. Stanislaus.

Jerry Costollo was a brakeman on a train of 18 loaded cars near Birmingham when the locomotive engineer failed to stop and ran into another train on the rail, killing Costollo, the engineer, and a train mechanic. The story of the railroad accident was telegraphed and published in the May 18, 1891 issue of the New York Herald. A worn memorial stone dedicated to Costollo is placed near the graves of Mary and Hanora Costollo (N08-15). A grave maker on the north side of the cemetery captures the eye in the vivid sunlight. An elegant white marble headstone marks the grave of Arsene Bontemp Estapa (N02-02). Though stained with green moss and dirt, what is unique about this headstone is the brightness of the marble and the depth of the engraving. Her place of birth is inscribed in graceful print and in the musical voice of the French language — “ne a la Baie S. Louis" (from Bay St. Louis). She died on October 10, 1875, in Hancock County, Mississippi. It goes without saying that there is an otherworldly nature to cemeteries. Whether it is based on our religious beliefs or our distance from decades or centuries of local life, the more we learn about cemeteries, the more they contribute to our understanding of the history of humans. Information regarding burials and purchasing plots in St. Mary’s should be directed to the Our Lady of the Gulf rectory at 228-467-6509. How to find a grave in St. Mary Cemetery

The Hancock County Historical Society surveyed and recorded St. Mary Cemetery, which is divided into a North and South sections, beginning with Necaise Street.

To find a gravesite, start on the main road through the cemetery and walk westward counting row numbers, beginning with #1. Based on the location data provided above, find the proper row. For example, Funston Mauffray is buried in S07-23d. To get to his grave, walk seven rows west then turn south. Counting gravesites southward, Mauffray will be buried in the twenty-third gravesite, along with other family members. Information regarding burials and purchasing plots in St. Mary’s should be directed to the Our Lady of the Gulf rectory at 228-467-6509. The Saucier-Post Tragedy

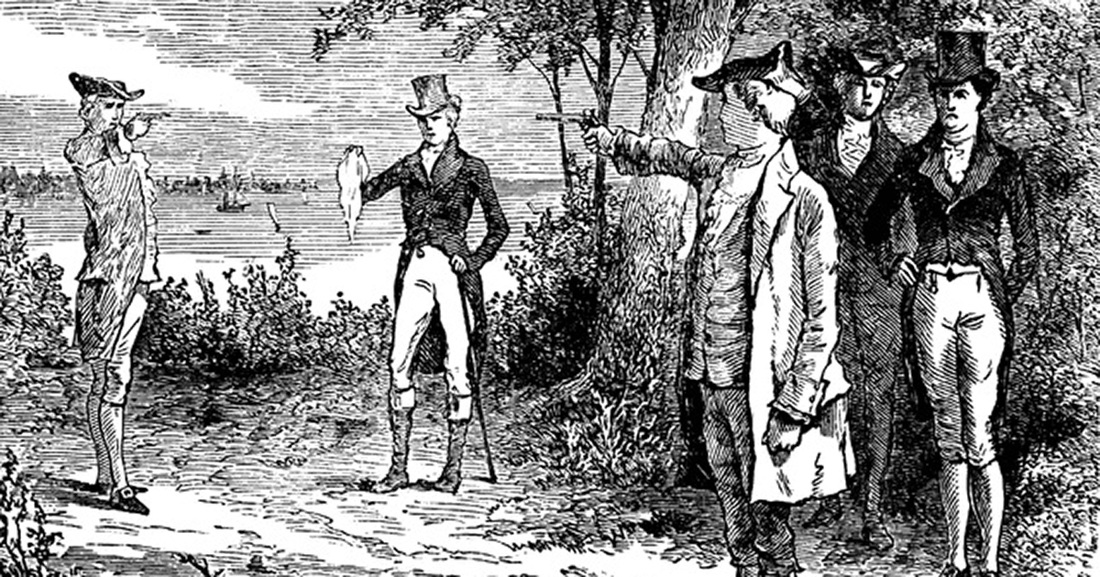

Opening a cold case from Bay St. Louis history leaves us with the lesson that the truth is hard to pin down.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photo Library of Congress

Excusing herself to leave and sit overnight with her ill mother, Madeleine Josephine Toulme Saucier left the Crescent Hotel to make the trek into the mid-spring night. The evening was slowly turning dark as Madeleine faded, unescorted, into the night. Her mother, Victoire Uranie Saucier, had been ill for weeks. After two hours, Madeleine’s husband Evariste Valerian Saucier became concerned, particularly since he had heard rumors of a relationship between his wife and a local doctor.

The cast of characters in this conflict echoes the names of well-established local families in Bay St. Louis and Shieldsborough during the 1800s. According to a bulletin from the New Orleans Advertiser reprinted on page one of the April 18, 1870 New York Commercial Advertiser, the lady involved in “improper relations” was the daughter of John B. Toulme. Mr. Toulme was a town leader, successful merchant, and landowner, and the original founder and manager of the Crescent Hotel (also known as the City Crescent Hotel) located at 200 South Beach Boulevard. A short walk from the train station, the Crescent was a popular stop for passengers and visitors to the shore. Evariste Saucier took over management duties of the hotel following a stint (1867–1869) as the U.S. Postmaster for Bay St. Louis. Church records show that the lady and her husband married October 1, 1851 with a 3-degree dispensation from consanguinity (they were second cousins who shared the same great-grandparents). She was 18 and her husband was 37. During their marriage, the couple had several children, the last born in 1868. Dr. Christopher Columbus Post (b. 1844) was an 1861 graduate of Tulane University Medical School. After serving his time in college-related duties, he relocated to Bay St. Louis to practice apothecary science. He married well to Irene Whitfield (b.1850), daughter of William Alexander Whitfield, owner of Shelly Plantation. The plantation was located on the plot of land where the DuPont plant is now located. As related in the New York and New Orleans newspapers, on the evening in question Mr. Saucier, along with a friend, went directly to his mother-in-law’s home and was told the lady had not been at the home that evening. Next, they walked to Dr. Post’s office, where they knocked on the locked door. The doctor answered the door and told Saucier and his friend that he was otherwise engaged. He closed the door without further discussion. Undeterred, Saucier and his friend stayed in the neighborhood and watched as Saucier’s wife exited the building and headed in the direction of the hotel. A few days later, Saucier challenged the doctor to a duel, which Post accepted. Local law enforcement stepped in and arrested both men. Peace was kept for a few days. The 1832 Mississippi state constitution strictly forbade dueling by “any rifle, shotgun, sword, sword-cane, pistol, dirk, bowie-knife, dirk-knife, or any other deadly weapon.” Seconds and physicians would be fined a sizeable sum and be imprisoned for three months. If a duelist was killed, the offending man would be arrested and tried on grounds of murder. Upon their release from the local jail, Saucier and Post returned to their lives and homes; however, the unanswered matter of honor weighed heavily on Saucier. Within a few days, he communicated with Post and told him to leave town or face the consequences. Post ignored the ultimatum and maintained his presence in the community. The Commercial Advertiser and New Orleans Bee reported that on April 7 around 7 p.m., Saucier waited and watched as the doctor exited the apothecary shop and walked down the street. Saucier surprised Post with several pistol shots in his direction. Post managed to get off one shot that hit Saucier’s hip before Post collapsed and died in the street. All of Saucier’s bullets had hit the mark. The prognosis for Saucier was unknown following the street battle. According to the New Orleans Daily Picayune, Saucier died on April 12 of his wounds. Regarding the death notices and obituary published in several national and local newspapers, Mr. Saucier’s death was met with deep sorrow, while Post’s death notice was simply acknowledged in the New Orleans papers. Following the deadly altercation, Mrs. Saucier moved her family to her father’s home in Pass Christian. In 1872, she married John Anthony Breath, a judge in the Hancock County judicial system. As with all historical research, some questions cannot be answered. In question is the location of the street duel: some newspapers reported that the night’s events took place in front of the Saucier home, while others suggested the street in front of the Crescent Hotel, or the Masonic hall, or Post’s apothecary shop. As to the accusations against Mrs. Saucier and Dr. Post, we find no published confession by either. Madeleine is buried in the Toulme family plot at Cedar Rest Cemetery in Bay St. Louis (Madeline Toulme Saucier Breath, Plot: S11-08). John Anthony Breath was buried in Masonic No. 1 in N.O. Post is also buried in New Orleans, in the Greenwood Cemetery (Plot 56, Cypress Hawthorne Cedar). No one knows Saucier’s final resting place. Valena Cecilia McArthur Jones

A church and two schools bear her name: Valena C. Jones. Her life wasn't a long one, but she left a lasting legacy.

- by Rebecca Orfila

Following her matriculation, Jones was named principal of the Bay St. Louis Negro School where she taught until 1897 when she accepted a position in New Orleans at McDonough School #24. During the McDonough teaching period, 1897 to 1901, Jones was voted the most popular black teacher in the city. When she married Rev. Robert Elijah Jones of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1901, her career as an educator ended. Married women were not allowed to teach in public schools at that time.

After her marriage, Valena helped her husband edit and publish the Southwestern Christian Advocate, a periodical of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Three years following her death in 1917, Rev. Robert E. Jones, Valena’s husband, was elected Bishop of the New Orleans Area (central Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas). Three centers of education and spirituality were named in her honor since her death: Valena C. Jones School in New Orleans and Bay St. Louis, and the Valena C. Jones United Methodist Church on Sycamore Street in Bay St. Louis.

Beginning in 1910, a citizens group in New Orleans 7th Ward saw the need in their community for a neighborhood school. Between fundraisers like dinners and dances, the group was able to purchase four acres for the construction of a small school. The first school was destroyed by weather events in 1916 and was replaced by a new structure built in 1918 near the intersection of Annette Street and North Miro Street.

The 1918 school was the first structure named in honor of Valena Jones. Due to its growing enrollment, the small school was replaced in 1929 with an impressive brick, three-story structure. According to the Chicago World issue of November 2, 1929, the school was “named after Mrs. Valena MacArthur Jones, formerly a teacher in the public school system in recognition of her outstanding ability as a teacher and for her uplifting influences among the people of her race.” Back in Bay St. Louis, St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church provided religious education to the black population and was originally located on Washington Street in Bay St. Louis. The first structure was replaced in 1922 with a larger church. Built in 1880 to provide religious education and support for blacks in the area, growing attendance levels required the construction of a larger church in 1922.

The influence of Valena McArthur Jones did not stop at the conclusion of her life or with the construction of the buildings that carry her name. In an oral history conducted by the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, Alonzo Merdis Daniels recollected excitement as a youngster for attending school “with the other fellows in our community.”

Daniels waited impatiently until he turned six to attend Valena C. Jones Public School in Bay St. Louis. Daniels attended from first through tenth grades, the highest level attainable at the school. Following Jones School, he attended St. Rose and completed his high school graduation with the class of 1931. While reminiscing, he praised his English teacher, Grace Claudia Jones Minor, one of Valena Jones’ daughters. Mrs. Jones died in New Orleans in 1917. She was interred in Greenwood Cemetery. The grave is unmarked but can be found in Plot 515, Pine Cedar Aloe, Daughters of Louisiana, Gravesite 5. If anyone has more information about Valena C. Jones and would like to add to the historical record of her life, please contact us at [email protected]. Hancock County Historical Society: Volunteer Driven

A crackerjack group of volunteers keeps the energy humming at one of the most respected historical societies in the country.

- story by Rebecca Orfila, photos by Rebecca Orfila and Ellis Anderson

The HCHS volunteer cohort consists of individuals with a love for history or a desire to give back to their community. Gifted with various talents and interests, each volunteer is invited to work in their area of interest or, with the assistance of the volunteer staff, match their skills with new or unfinished projects. With a smile, Charles Gray, the Executive Director of HCHS, confirmed that volunteers are provided a wide berth on their volunteerism and schedule: “Whatever works for you, works for us.”

Volunteers can serve in many ways at HCHS. Several professional and avocational historians contribute quality articles to the monthly newsletter, The Historian of Hancock County. During a post-luncheon chat with a few of the volunteers, James Keating spoke of being inspired by Eddie Coleman (the editor of The Historian) to pursue his interest in the economic history of this area. Keating, a New Orleans native and retired physician, has been published in The Historian several times, most recently in the April 2016 issue with his article “The Turpentine Industry in Hancock County.” Other well-known contributors to The Historian include Coleman, Scott Bagley, and Russell Guerin. According to Coleman, submissions for The Historian are invited. If you are interested in submitting an article, contact the Society via the address or number listed below.  Scott Bagley Scott Bagley

Historical societies gather, organize, and share information with researchers, genealogists, visitors, and other interested parties by making paper or digital documents available to the public. HCHS maintains documents and indexes of local cemetery records, for example. These resources — and much more — are available to the general public at the Lobrano House in downtown Bay St. Louis and on the Society’s ever-expanding website, where the cache of digitized records available for research increases every day.

Through the efforts of volunteer researchers, writers, computer aficionados, organizers, and “boots on the ground” folks, the Society continues to add to their collection. Many local and New Orleans families have donated records and images, which are scanned for archival and research purposes. Personal materials, including private letters, tell stories and even provide details on confidential matters. According to Gray and Coleman, the Society does not censor when asked for information. No matter what the contents of a letter, album, or image, any donation will be made available to the public. “We don’t want any secrets,” Gray said. The amount and accessibility of resources at the Hancock County Historical Society has raised the bar for other county and city societies to provide research materials and educational events to the interested public. As noted by Gray, “Our ultimate goal is to consign all the written documents on Hancock County history that we can gather into a database that will provide instant access to information being sought.”

“We all learned a great deal from Katrina,” recalled Coleman. The hurricane was a major impetus for increased focus on digitizing.

Over the years, HCHS has received and cataloged thousands of primary (original papers, images, and maps) and secondary (books, annuals, and reproduced images) resources. Cataloguing documents takes a great deal of time. A collection of photographic negatives from Anthony Scafidi, a prolific Bay St. Louis photographer of the late 1940s through the early ’60s, for example, took multiple volunteers an entire year to clean, scan, and print for conservation purposes. Marianne Pluim, volunteer webmaster and computer pro, shared her thoughts on digitizing materials for public access and archival protection. According to Ms. Pluim, having access to cemetery, marriage, divorce, and land records online has made it possible for researchers at a distance to find key elements to their genealogical or historical research. Also, between 125 and 150 people actually visit the HCHS each month for research purposes, and having the digitized materials helps to make research time less lengthy. It also secures these important resources in case of natural disaster. Volunteer Beth Weidlich, like Marianne, is interested in saving a large quantity of materials for posterity. A regular Tuesday volunteer, Beth is deep into a project to scan materials located in the vertical files for uploading. Ana Balka works alongside Weidlich on the resources archive project, and recognizes the importance of history to county residents, but also to newcomers to the area. A transplant herself, Ana sees opportunities to expand our understanding of history in Hancock County by researching for example, the economic ebb and flow of businesses before and after catastrophic weather events, or for deepening our understanding of African American history in the county.

Dot Larroux Kersanac, another volunteer, is working on her own project. She is crusading to gain a Magnolia Marker for Cedar Point, where her family has had a presence for many years. A former teacher and respiratory therapist, her work-in-progress began in October 2015.

The Historical Society is concerned with more than paper documents. The Society and the Bay-Waveland Garden Club work together to register Hancock County’s oldest live oak trees, with volunteer Shawn Prychitko at the helm of those efforts. Read in-depth stories from the Cleaver about live oak registration here and here. Jim Thriffiley, 1st Vice President, is in charge of scheduling the monthly speakers. When asked what qualities a speaker should have, Thriffiley responded, “Warm, receptive, and clever.” Eddie Coleman said that people from many countries and states have contacted the Historical Society for assistance in research or genealogy. Between in-person visitors, telephone calls, and email inquiries, the daily workings and research fill the day for volunteers. The HCHS Board of Directors are all volunteers: Board President is Marco Giardino; Jim Thriffiley is 1st Vice President; Jackie Allain 2nd Vice President; Lana Noonan, Secretary; Georgie Morton, Treasurer. Scott Bagley, Publicity Chairman; John Gibson, Historian; and Ames Kergosien, Member-at-Large. This year on October 31st, the Society will hold its 23rd annual cemetery tour in Cedar Rest Cemetery. According to Gray, the event needs many volunteers every year to be successful: 10-12 to portray historical figures buried in the cemetery, another 10-12 to serve as guides, and several to welcome visitors to the Lobrano house, where guests are invited after the tour. As noted on the Society website, “All talents are welcome. No experience required.” Come join in the fun and help preserve Hancock County history. For more information on volunteering, possible submissions to the newsletter, or research, contact HCHS at 228-467-4090 or [email protected]. Lost Childhoods

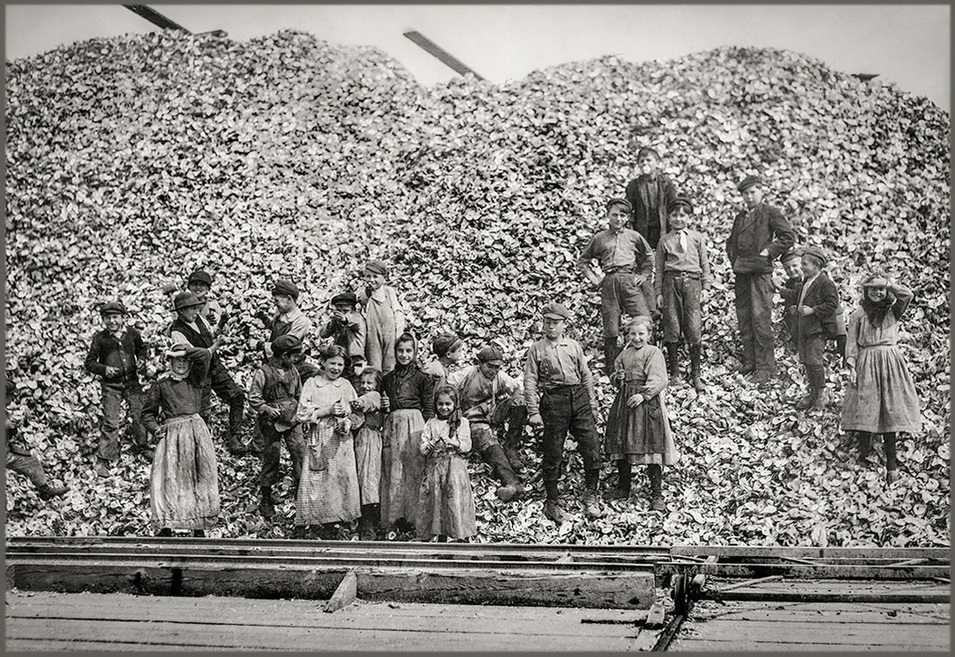

A restored collection of historic images by legendary documentary photographer Lewis Hine tells the poignant story of children who worked in the Mississippi coast seafood industry.

- story by Ellis Anderson, photos by Lewis Hine and Joe Tomasovsky

But Sadie is better off than some of the other children Hine has photographed. She is wearing shoes. They’re battered, but they provide some protection from the acid of the shrimp that eats holes in leather soles. Some of her young friends work with bare feet.

The images recall an era when profit was the unabashed king of the country. Compassion for one’s fellow man was the province of church ladies, not serious businessmen. Attempts to establish regulations to protect workers’ lives were scorned by wealthy tycoons. Burdensome bureaucracy and government meddling, they called reform measures. How can we provide jobs if we’re hamstrung by regulations? Some of the cheapest sources of labor were children. No matter the industry or its location in the country, profit margins soared by paying desperate adults starvation wages. They went up even further if the family’s children worked as well. Children were paid a fraction of the pittance the adults earned. They were nimble, too, their small fingers able to perform often-dangerous tasks that adults could not.  Lewis Hine Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine was a teacher so moved by the plight of child workers that he left his job and went to work for the National Child Labor Committee, a private, nonprofit organization founded in 1904. According to the book “Kids At Work” by Russell Freedman, Hine became an investigative photographer in 1908, concocting ruses to get onto jobsites with his camera. It was dangerous work, and he risked beatings and worse to tell the visual story of childhoods lost to greed:

“If people could see for themselves the abuses and injustice of child labor, surely they would demand laws to end those evils. His pictures of sooty-faced boys in coal mines and small girls tending giant machines revealed a shocking reality that most Americans had never seen before.”

Joe Tomasovsky, a retired photography teacher who lives Bay St. Louis, restored digital files of Hine’s original work, which can be found in the Library of Congress. The library contains over 7000 images of children at work that Hine shot during his career.

Joe, who grew up in Gulfport, had taught Hine’s work to his Florida photography students for years before his retirement, but only recently discovered that Hine had taken pictures on the Mississippi coast. He felt the images needed a wider audience and began the restoration project as part of his work with the Mississippi Gulf Coast Museum of Historical Photography (MOHP). According to Joe, the digital files in the Library of Congress are scans of contact prints made from Hine’s original glass 5-by-7-inch negatives. He sifted through the thousands of available images Hine took in his travels to find ones relevant to the Gulf Coast and the seafood industry.

While the quality of the images has suffered from age, poor processing, and repeated duplications, Joe spent hours meticulously restoring each one of the digital files to more accurately reflect the original quality. He then printed the files in large sizes (up to 24 by 38 inches) onto archival canvas, allowing the images to be viewed without a barrier of glass.

“These people that Hine photographed in this series were mostly immigrants,” says Joe. “They were known by the derogatory term ‘shrimp pickers.’ They dressed differently and they couldn’t speak English, but they had an incredible work ethic and earned a lot of respect. Many of their descendants are still here on the coast today.