Lost Childhoods

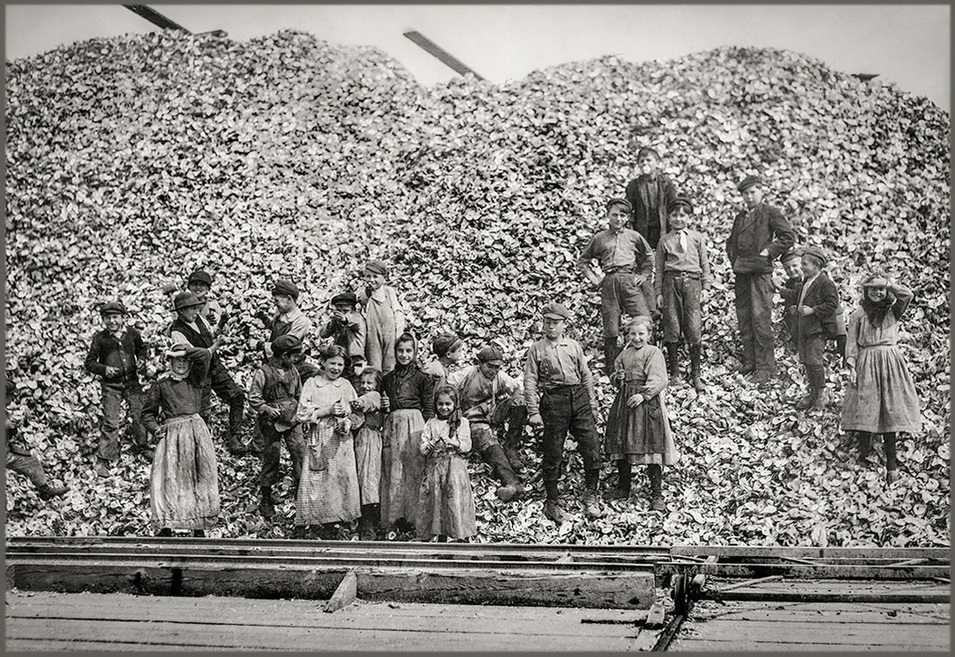

A restored collection of historic images by legendary documentary photographer Lewis Hine tells the poignant story of children who worked in the Mississippi coast seafood industry.

- story by Ellis Anderson, photos by Lewis Hine and Joe Tomasovsky

But Sadie is better off than some of the other children Hine has photographed. She is wearing shoes. They’re battered, but they provide some protection from the acid of the shrimp that eats holes in leather soles. Some of her young friends work with bare feet.

The images recall an era when profit was the unabashed king of the country. Compassion for one’s fellow man was the province of church ladies, not serious businessmen. Attempts to establish regulations to protect workers’ lives were scorned by wealthy tycoons. Burdensome bureaucracy and government meddling, they called reform measures. How can we provide jobs if we’re hamstrung by regulations? Some of the cheapest sources of labor were children. No matter the industry or its location in the country, profit margins soared by paying desperate adults starvation wages. They went up even further if the family’s children worked as well. Children were paid a fraction of the pittance the adults earned. They were nimble, too, their small fingers able to perform often-dangerous tasks that adults could not.  Lewis Hine Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine was a teacher so moved by the plight of child workers that he left his job and went to work for the National Child Labor Committee, a private, nonprofit organization founded in 1904. According to the book “Kids At Work” by Russell Freedman, Hine became an investigative photographer in 1908, concocting ruses to get onto jobsites with his camera. It was dangerous work, and he risked beatings and worse to tell the visual story of childhoods lost to greed:

“If people could see for themselves the abuses and injustice of child labor, surely they would demand laws to end those evils. His pictures of sooty-faced boys in coal mines and small girls tending giant machines revealed a shocking reality that most Americans had never seen before.”

Joe Tomasovsky, a retired photography teacher who lives Bay St. Louis, restored digital files of Hine’s original work, which can be found in the Library of Congress. The library contains over 7000 images of children at work that Hine shot during his career.

Joe, who grew up in Gulfport, had taught Hine’s work to his Florida photography students for years before his retirement, but only recently discovered that Hine had taken pictures on the Mississippi coast. He felt the images needed a wider audience and began the restoration project as part of his work with the Mississippi Gulf Coast Museum of Historical Photography (MOHP). According to Joe, the digital files in the Library of Congress are scans of contact prints made from Hine’s original glass 5-by-7-inch negatives. He sifted through the thousands of available images Hine took in his travels to find ones relevant to the Gulf Coast and the seafood industry.

While the quality of the images has suffered from age, poor processing, and repeated duplications, Joe spent hours meticulously restoring each one of the digital files to more accurately reflect the original quality. He then printed the files in large sizes (up to 24 by 38 inches) onto archival canvas, allowing the images to be viewed without a barrier of glass.

“These people that Hine photographed in this series were mostly immigrants,” says Joe. “They were known by the derogatory term ‘shrimp pickers.’ They dressed differently and they couldn’t speak English, but they had an incredible work ethic and earned a lot of respect. Many of their descendants are still here on the coast today.

“Hine believed he could use photography as a political tool to bring about change for these people. He was part of what’s now known as the Progressive Movement.” The George Washington University website defines those early Progressives as “people who believed that the problems society faced (poverty, violence, greed, racism, class warfare) could best be addressed by providing good education, a safe environment, and an efficient workplace… They concentrated on exposing the evils of corporate greed, combating fear of immigrants, and urging Americans to think hard about what democracy meant.” Lewis Hine lived long enough to see his work have a major impact. In 1938, Franklin Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act into law, a federal mandate that prohibited children under 16 from working in manufacturing and mining. Hine died in 1940, before the law was strengthened in 1949 to include other types of jobs. But child labor is still a major issue worldwide today (including in the United States) so the work of Hine continues to be relevant, generations later.

Joe explains how Hine’s final years were spent as a pauper, cut off from financial support for his work by the powerful figures he’d exposed through his photography.

“But no one could diminish the power of his work. This exhibit is a tribute to what one man was able to accomplish using the lens of his camera.” The Bay St. Louis Library plans to host part of the Hine exhibit sometime later in 2016, focusing on images from Bay St. Louis and Pass Christian. Keep on eye on our Upcoming Events page; details will be posted there as soon as they’re available. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed