A Newcomer's Reconciliation

Learning to see the invisible net of community - woven from both past and place - enriches the life of one suburban transplant.

- by Ellis Anderson

I was baffled. After being a part-time Bay resident for years, I’d just moved over full-time from “the city.” In New Orleans, one attended the grand opening of a business expecting to receive, not to give.

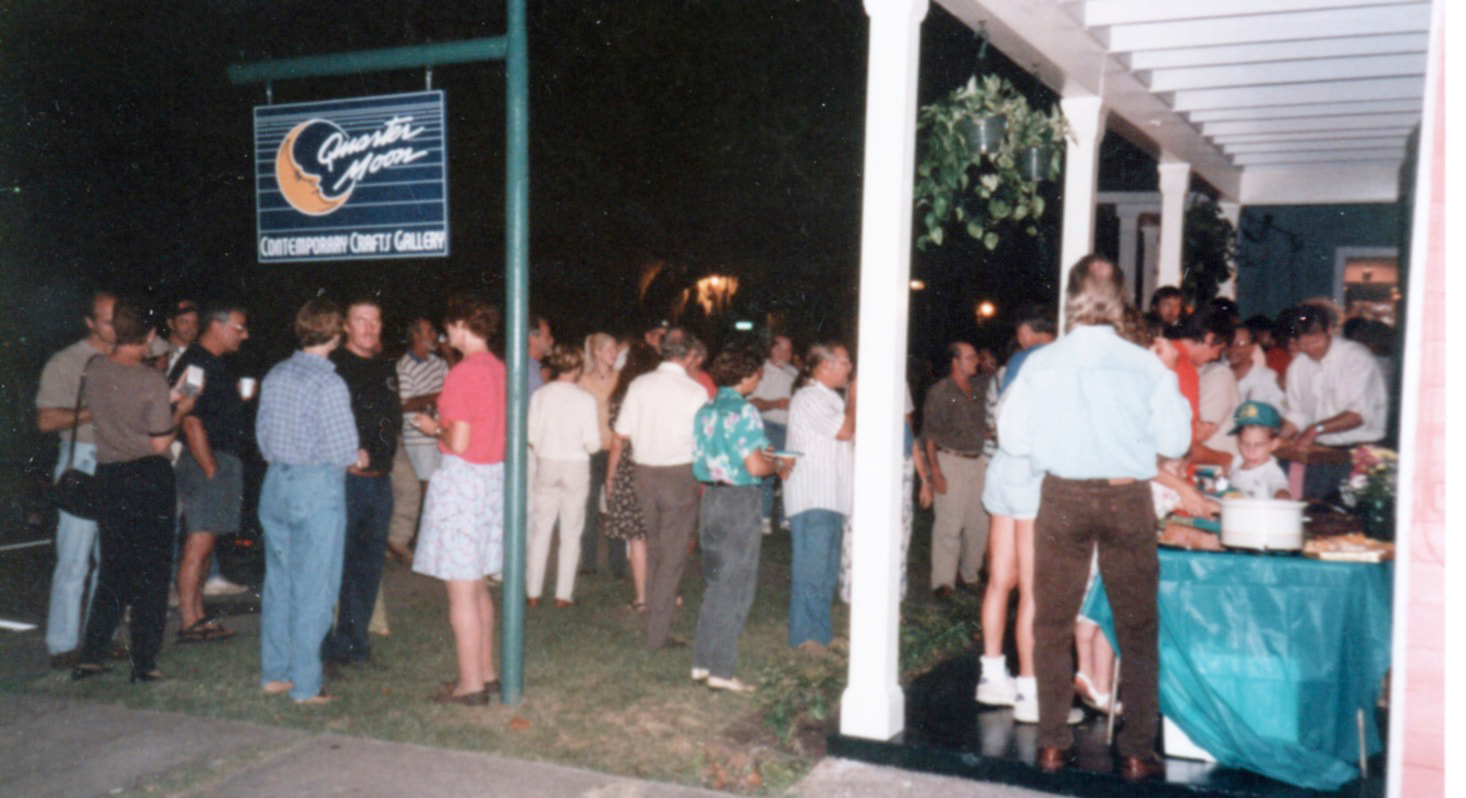

But since I’d blown my party budget by hiring a great band, there wasn’t much left to spend on refreshments. So my answer was, how about bringing a little snack, like potato chips or pretzels? On the designated night, hundreds of people – or at least it seemed like hundreds to me – streamed down the sidewalks toward the gallery, plates of food held before them. Friends had to fetch more folding tables to hold the feast. Soon every available surface on the gallery’s porch was filled with casseroles and cakes, shrimp pastas and sandwiches, salads and brownies. At one point in the party, an astonished friend who’d driven over from the city asked who my caterer was. “They are!” I said, gesturing toward the crowd gathered on the gallery’s front yard and dancing in the driveway. Tears sprang to my eyes several times that night. I’d never imaged such a generous a community could exist. I felt embraced, like the new member of an extraordinary tribe.

But I didn’t know enough local history then to understand that I’d always be the new kid on the block. Being a real local is an accident of birth. While newcomers may live here for decades, if someone in Bay St. Louis or Waveland says that they’re a native, it’s likely their ancestors settled here two centuries ago. Or longer.

A short time after my gallery opening, one local startled me by saying his family had been residing in Hancock County for nearly 300 years. That’s a good example of hyperbole, I thought. Then he explained that his direct ancestor had been one of D’Iberville’s crew members when the explorer claimed the territory for France. In 1699. Later, I’d see censuses from the early 1800s, filled with names of my neighbors. Like Dubuisson and Dedeaux, Morain and Ladnier, Labat and Socier. Necaise, Quaves, Garcia, Lafontaine, Baribino and Seal. While the spelling and pronunciation of the names may have changed a bit over the centuries, for the most part, the families’ attachment to this place has not. I try not to be jealous. My own heritage is more free-floating, although I did trace one ancestor back to the 1700s. My multiple-great grandfather, Isaac Anderson, fought in the Revolutionary war. Then the Scotch-Irish immigrant homesteaded as far from civilization as he could, settling in a remote corner of North Carolina’s Appalachia. But the Great Depression scattered his descendants from that Blue Ridge cove. By the 1960s, only one of my mother’s six siblings still lived in Ashe County. My parents landed in Charlotte, where I grew up. In just a few hours we could drive to my mom’s hometown of Crumpler (which boasted one general store/gas station/post office) – but it was light-years from the city. Charlotte’s population was exploding at the time. To further entice developers, the city sold its birthright: thousands of irreplaceable historic buildings were razed, ones that graced its streets and served as emotional anchors to its citizens. Residents swung in and out of Charlotte's teeming ranch-house neighborhoods so fast the Welcome Wagon had to chase them. I graduated from a newish high school 100 times the size of Crumpler. Its 1,500 students were pulled from a 10-mile radius. Our most popular community gathering spot on the weekends? The mall. I moved away for good in 1976. While I missed my parents, I never once felt homesick. That particular malaise requires connection to a place. While Charlotte’s got a lot going for it, endearing it’s not. Many millions of suburbanites like myself have been raised without a stabilizing core of long-term residents in their neighborhoods. In cloned and characterless landscapes jammed with strip malls and billboards, gas stations and fast food joints, we find nothing to cherish.

Then, there’s life on the Mississippi coast.

It seems everyone who grew up in Bay St. Louis has their favorite childhood fishing spot, or tree, or place on the shore where they have watched sunrises. They experienced their first kisses on the porch swing of their aunt’s house, or the steps of the old city hall. They can point to just about any cottage in town and reel off the names of those who grew up within those walls, who was born in the back bedroom or married in the yard. They might transport you with a story about camping in that very attic with other rambunctious kids, determined to catch a ghost. Longtime locals can stand before an empty lot and perhaps see a three-story house that no longer exists – and its roofline their grandmother walked across as a girl, just to satisfy a dare. Or they can gesture to the spot on the beach where their daddy launched a sailboat he and his brothers built over an idyllic summer. Coast natives see threads of continuity running everywhere through the landscape. They can pick up an end anytime they choose and follow it back generations. These ties are invisible to newcomers at first, but I can see more every year I live here. Each story told by a local reveals another strand that’s woven into an astonishing, yet invisible net of fellowship. While it may not be my family's net, simply knowing it exists imparts a certain kind of peace. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed