Way Back When

Most people know Nan Parati as one of the creative forces of Jazz Fest and owner of Elmer's, an iconic New England restaurant. Here's the little-known backstory of her first creative enterprise.

- by Ellis Anderson

I found that out back in high school, when we were assigned seats next to each other in orchestra class. Nan and I had actually met when we were 12. We didn’t like each other at first. Then we went to different schools for a few years and by the time we met up again in 10th grade, the friendship stuck.

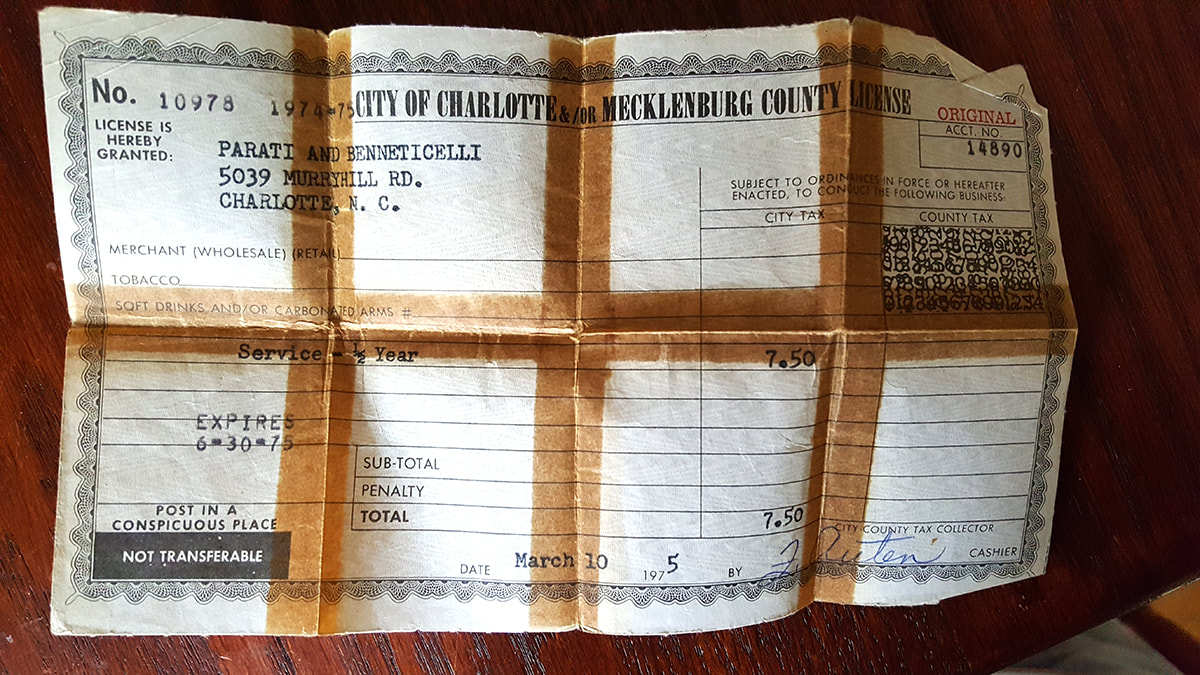

She became my first business partner in 1975, when we were high school seniors in Charlotte. We had a good reason for becoming early entrepreneurs. Nan had spent the summer before as an exchange student in France. She proposed the majestic plan of the two of us going back to France on our own – unsupervised and unchaperoned. We’d travel during the summer between graduation and college. We’d backpack. We’d buy Eurail passes and travel all across Europe and sleep in hostels and train stations and on the trains themselves. I was in. I’d written down my life’s goal at age 15: to be an adventurer. Nan’s vagabonding-across-Europe scheme seemed the perfect way to start. Our parents were less than enthused. My parents were older, very conservative and frankly horrified. Even Nan’s hip, liberal, artsy parents expressed reservations, which was surprising to me. They’d practically been beatniks and had campaigned for Eugene McCarthy. We came to suspect later that the four parents secretly conspired. They even used some of the same expressions when they talked to us about our aspirations. Each set of parents (individually and oh, so casually) told us that we were welcome to go. After all, they couldn’t prevent us. We’d be 18 and legally adults. They’d send us off with their blessings. All we had to do was raise the money for the trip. It must have seemed a foolproof approach to our parents. That was in January. We planned to go in June. But in Nan’s mind, their stance represented a challenge, not an impossibility. We opened our own business. Since Nan had the interesting Italian name and I’d been born with the lackluster English one — Bennett — I took liberties on the business license that we went downtown to purchase. I wrote “Parati and Bennicelli” on the application. I still remember riding down in the elevator in that tall government building with that amazing document in our hands, the one that validated our dreams. We were giddy with giggles. A stodgy businessmen who rode down with us arched his eyebrows and moved toward the opposite corner. We laughed harder. Our business motto became “We Do Anything Legal.” Nan hand-lettered a flyer with that slogan as the heading. Below, tasks that we felt qualified to take on were listed in two columns. While the business license and an original flyer were lost in Hurricane Katrina thirty years later, we still remember several items from that list: Washing houses. Baking cakes. Cutting hair. This last one gives me shivers now, but we actually had hippie friends who allowed us to take scissors to their long locks and then gave us money. We did all of those things and more. In the mornings, Nan taught me French in school stairwells during class breaks, then in afternoons, we collected soft drink bottles from park garbage cans; they could be turned in for a few cents apiece back then. We babysat, while calling the toll-free numbers of airlines incessantly to compare ticket prices. I even got a job selling popcorn at a local movie theatre. But our big moneymaker, the legal thing we did that paid for the lion’s share of our tickets that spring, was painting house numbers on curbs. Do they do that anymore? Probably not, with the rise of GPS. But back in the seventies, we were able to sell it as a safety feature. “It’s often difficult for firemen or policemen to find your house in the dark,” we’d say to any hapless homeowner who answered the knock on their door. “If your house number is painted on your curb, there’s never any confusion.” It seems inconceivable now in these days of every child having a cell phone "just in case," and the understanding that mass murderers could lurk behind any ranch house door. Yet, we went house to house, armed only with our naïveté. We’d ring a bell and launch into our pitch. Nan would canvass one side of a street while I took the other. Nan had lettered a sign on a piece of plywood and we took it with us to prove our legitimacy as a business. On one side was our business name. We’d flip it over to reveal a house number sample.

I remember we charged $2 per house. Nan remembers $3. Even then, it wasn’t much, but we had competition. Serious, adult-run companies that used stencils. However, we had an engaging pitch and would point out our advantages. We hand-lettered our markers so they were more artistic (although the homeowners on my side of the street probably suffered buyer’s remorse). We used quality paints that would last (I know because the one I painted at my folks’ house was still visible, 40 years later).

Many afternoons that spring, we kneeled on the asphalt and painted, concrete as our canvas. Afterward, we would take our earnings — mostly in coinage — to the First Union bank on Park Road, where we opened a savings account. The tellers soon came to know us by name and took an interest in our far-fetched project. They were probably taking bets on the side. Could those reality-challenged girls actually earn enough money for a trip to Europe? Somehow, with Nan as a partner, my faith never wavered. I had no doubts. We sent those sweet tellers postcards from Europe that summer, from at least three of the 13 different countries we traveled to on our Eurail passes. I still have my journal from that trip, with illustrations by Nan. It’s filled with the wacky episodes of two innocents abroad. For instance: at one point, we boarded a night train bound for Berlin. European trains back then had compartments, like we’d seen in old mystery movies. This one was packed. People stood in compartments where every seat was already filled. The only empty compartment had a sign written in German hanging on it. Being youthful and brash, we ignored the sign, entered, and closed the door behind us. We shucked off our packs and sank down with relief into the padded seats. Maybe we’d even get to sleep on the long trip. Then we noticed Germans stopping outside the compartment in the passageway. They’d look through the glass doors at us and then at the sign. And then back at us again. They’d frown. They’d pass without entering. As the train gathered speed and this trend continued, we began to be concerned. Nan, who’d studied German all through high school tried to interpret the sign. The long compound word wasn’t in her German dictionary. The best she could figure was that it meant “heavily damaged.” Alarmed, we examined the floor to see if it showed signs of caving in. We checked the windows, wondering if one would pop out. Finally, overcome with fatigue, we pulled the compartment curtains and slept soundly through the night. In Berlin, German friends of Nan’s family met us at the station. Later, when I asked, they were able to solve the mystery. “Let’s see,” said one. “In English? I think a good interpretation of the sign would be the word ‘quarantined.’”

At the end of the summer, when I came back to the states, I was a different person. Thanks to Nan, I believed that anything was possible if I set my mind to it. If I imagined something, it could be manifested with determination and hard work.

Of course, that hasn’t turned out to be completely true. Through the years, both Nan and I have worked toward many goals that never came to fruition. But at least they were always interesting goals. A few years after the European trip, I moved to New Orleans and Nan visited me there. It wasn’t long before Nan ended up adopting the city herself. We were both convinced it was the most vibrant place in the United States. To me, the historic buildings of the Quarter were like transformers, with creative energy emanating from them with a sizzling electrical force. I could actually see its glow on some nights. No wonder Tennessee Williams, one of my literary idols, lived in the neighborhood. I was sure he could see it too. Nan and I both pursued creative endeavors. She eventually worked for the very first Whole Foods store that ever existed, on Esplanade Avenue. In charge of their marketing and advertising during those seminal years, Nan set a bar that three decades of corporate chain management has been striving to top ever since. I still see the Stamp-Of-Nan whenever I’m shopping one of the chain’s many stores, no matter which city I’m in. If you’ve been to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival at any point in the last 32 years, you’ve seen Nan’s work up there on stage with some of the world’s greatest musicians. She and Bill Darrow are the festival's stage and décor designers. Nan’s is also the hand behind every sign that identifies the hundreds of musicians and artists each year. The signs have become prized memorabilia trophies. Nan’s lettering - which I often think of as having being honed painting house numbers on curbs - is sometimes referred to as the official Jazz Fest font.

And if you live in the state of Massachusetts, you’ve probably heard of Elmer’s Store in the teeny village of Ashfield. Nan happened to be visiting friends there when Katrina struck. Since she couldn’t go home to New Orleans, she bought a defunct general store and turned it into a restaurant that’s become a regional symbol of creativity. Reading the breakfast menu alone would have been reason enough to visit (note: Nan sold Elmers in 2018).

If I happen to meet someone from the Northeast, I’ll mention Elmer’s to them. Chances are they’ve been there at one point in the last decade, or at least heard about the restaurant. It’s an experience, they’ll say. That woman has created an amazing center of community, they’re also likely to say. When I tell them that woman was my best friend in high school, they’re inevitably impressed. I suddenly become a person of potential interest because of my connection to Nan Parati. They don’t know the details of our North Carolina partnership or of our New Orleans adventures, or the night spent in the quarantined train compartment. Yes, I tell them. I knew her way back when.

Nan Parati is also our guest columnist this month. Click here to read her thoughts about Bay St. Louis!

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed