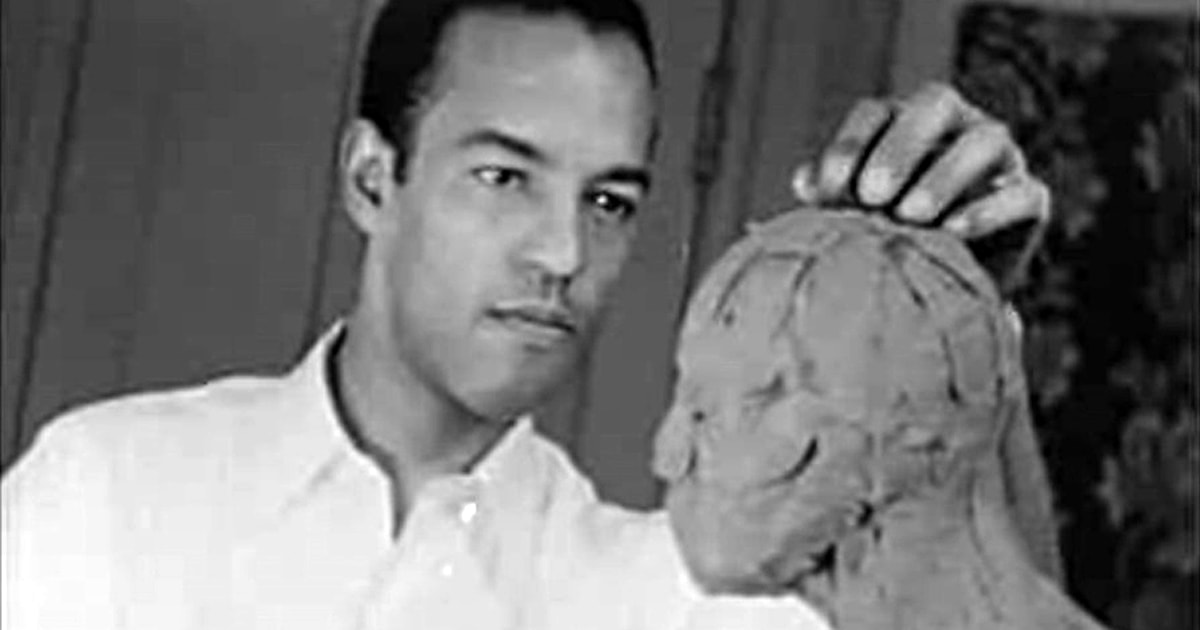

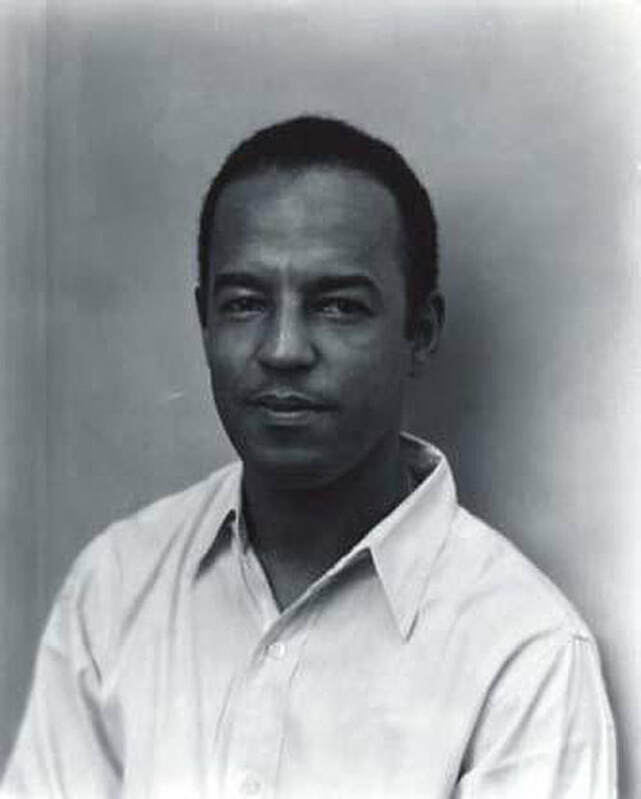

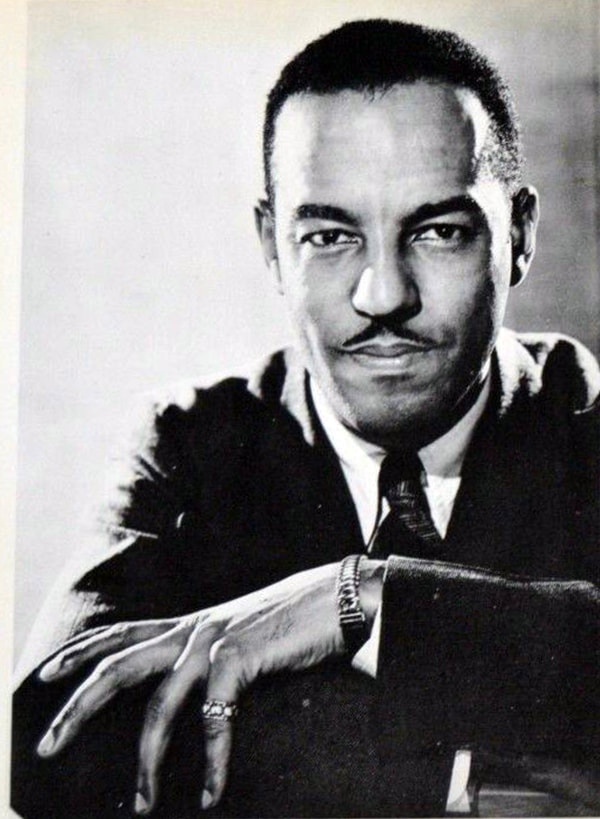

Richmond Barthé left Bay St. Louis at age fourteen. He became one of 20th century America’s greatest sculptors of the human form - and Mississippi’s preeminent artist in the field.

- story by Edward Gibson

According to Celestine Labat, in the oral history preserved by Lori Gordon, Barthé was pronounced like “hearth.” His mother, the Creole Clemente’ Rabateau, hailed from a family of craftsmen, and his father, Richmond Barthé, an “American” as the Creoles disparaged, was a dark-skinned, grey-eyed African-American. The elder Richmond died within months of Jimmy’s birth.

Jimmy enrolled at the newly formed St. Rose school where he met Celestine Labat’s sister, Inez Labat. The teacher Labat recognized Jimmy’s talent for drawing and encouraged him with both praise and a supply of pencils and paper. Inez Labat encouraged the young artist throughout his life. Jimmy’s talent for portraiture soon drew the attention of the town, and the Pond family from New Orleans hired the young boy to work at their summer home. In the early twentieth century, African Americans could go only so far in school and when Jimmy completed the eighth grade, he moved with the Pond family to New Orleans. Through the Ponds, Jimmy met Lyle Saxon, editor of the Times-Picayune, and future biographer of Jean Lafitte. Saxon, hardly ten years Jimmy’s senior, purchased Jimmy’s first oils and canvas. Barthé’s biographer, Margaret Rose Vendryes, in “Barthé: A Life in Sculpture,” hypothesizes that the two shared an intimate relationship, though there is no certain evidence to support this. Saxon sent Jimmy on false errands to Delgado where he could view the school’s classical art collection, a collection not generally available to people of color. At twenty-three, Jimmy Barthé rendered a portrait of the Savior for a church bazaar which impressed Saxon. He attempted to have Jimmy enrolled in Delgado College - without success. Undeterred, and with the assistance of the local parish, Jimmy Barthé applied to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago accepted him. Had Barthé attended the Pennsylvania school, he would have matriculated with Walter Anderson. With a modest fellowship from the parish in New Orleans, Barthé took up residence in the home of his Aunt Rose in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. He attended night classes at the Art Institute and turned his attention to sculpture by accident. He was facing difficulties capturing the third dimension in his painting and an instructor suggested sculpting in clay. Classmates sat as models and Barthé created two busts. The transformation was complete. He was no longer Jimmy Barthé but Richmond Barthé (pronounced “bar-tay”). In 1927, Richmond Barthé exhibited in a show called The Negro in Art Week. Critics panned the show, but praised the success of Richmond’s two busts, and he drew the attention of Chicago’s philanthropists, notably Julian Rosenwald. With their encouragement, Richmond established a studio in Bronzeville and created the first of many opuses, among them “Tortured Negro” (1929) and “Black Narcissus" (1927). The former was modeled on the classical pose of St. Sebastian, who was tied to a tree/post and pierced with many arrows. The piece has been lost, according to Vendryes: “dimensions and location unknown.”

Inez Labat visited the Bronzeville studio in 1929. According the Celestine, Inez found Richmond Barthé eating canned beans and the “soles of his shoes were flapping.” Labat took the impoverished young Barthé to a cobbler and “gave him some change.” In gratitude Richmond sculpted Inez Labat, “La Mulatresse” (1929), in plaster and gave it to her.

That year Richmond Barthé received the first of two Rosenwald fellowships. With this money and funds he received from a successful one-man show, Richmond Barthé moved to New York City and into the heart of the thriving Harlem Renaissance. There, he met African American luminaries such as Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Alaine Locke and Ralph Ellison. In New York, he became simply Barthé. Over the next twenty years, from studios in Harlem and in Greenwich Village, Barthé created his body of work and enjoyed success that the Jimmy Barthé could have only imagined. Barthé sold pieces to the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art as well as to wealthy collectors. He crafted “Blackberry Woman” (1930), his first major piece after moving to New York.

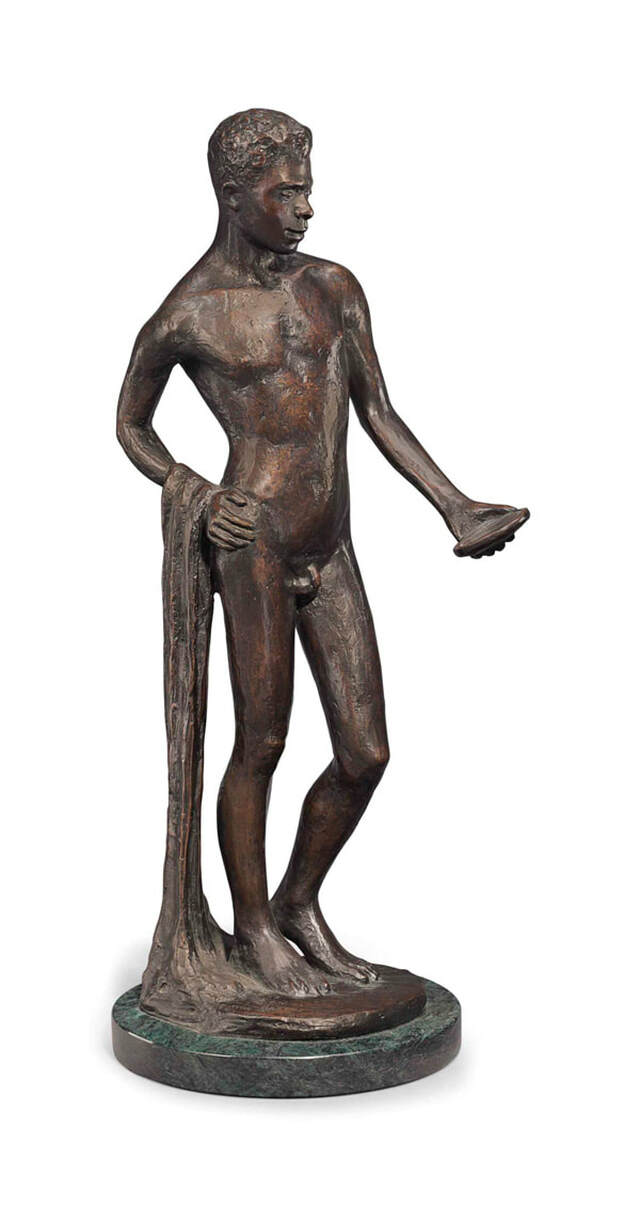

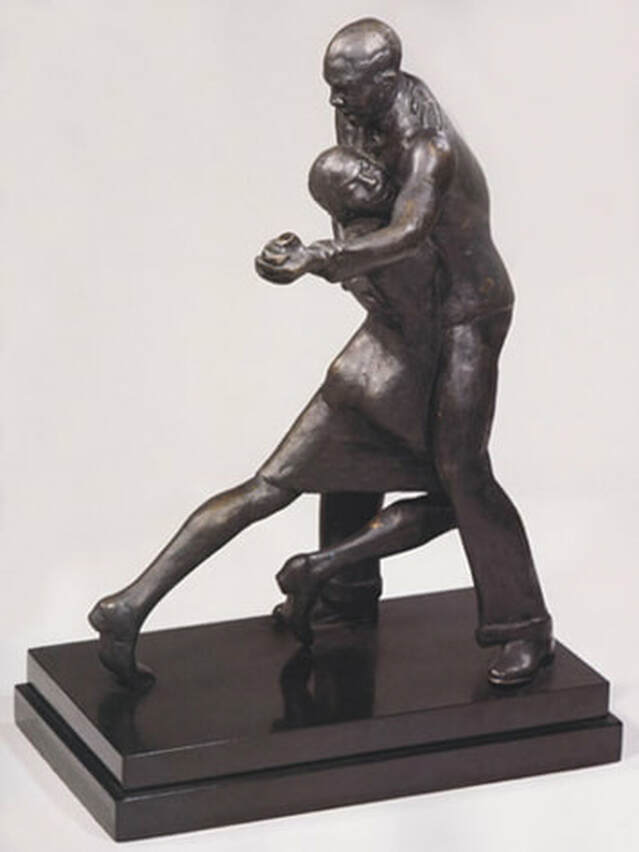

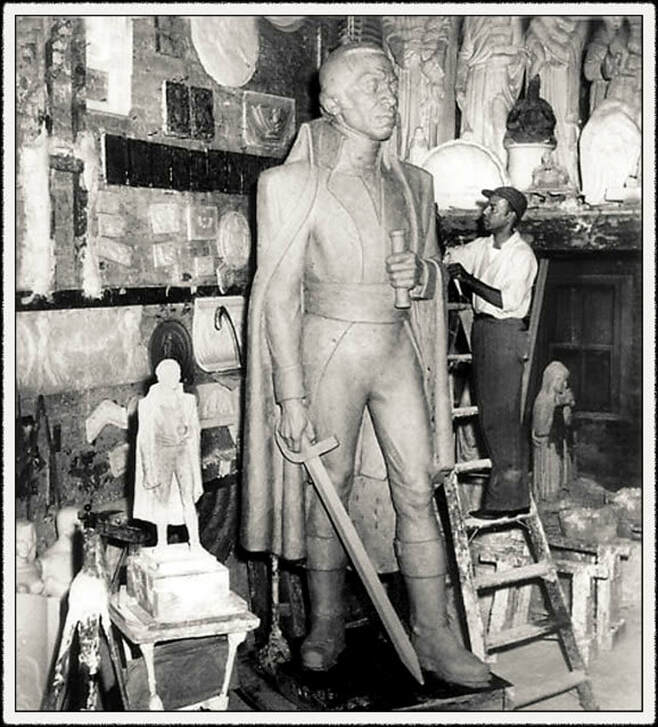

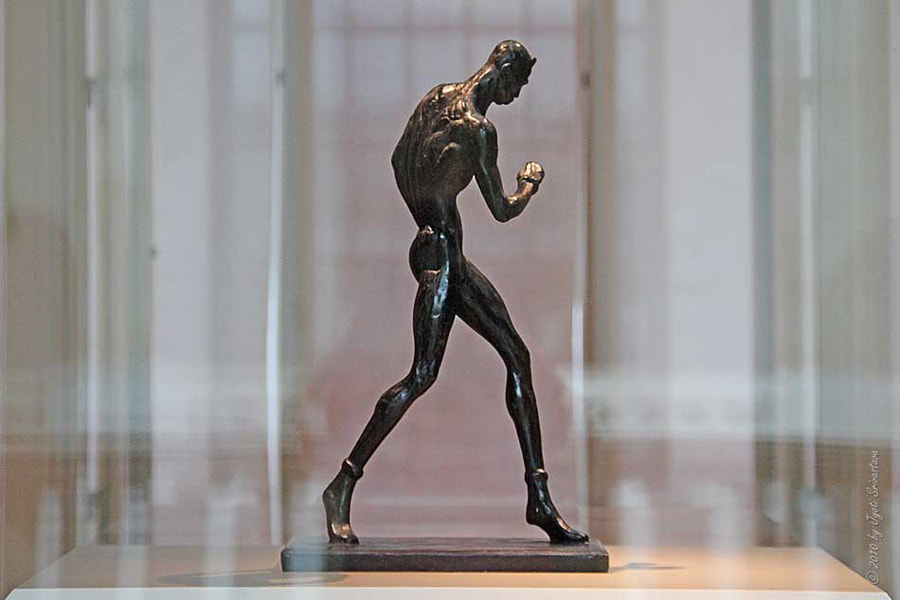

In 1935, Barthé exhibited at the Rockefeller Center alongside Matisse and Picasso. His sculptures, including “Feral Benga” (1935), “African Dancer” (1933), and “Wetta“ (1934), received more praise from critics than his more well-known contemporaries. Also in 1935, Barthé crafted his most political work to date. “The Mother” depicted a women holding the lifeless body of her son, the noose still hung about his neck. Sadly, Barthé, never comfortable as a dissident, later destroyed the piece. Barthé installed several public commissions, including a frieze in Harlem, “Exodus and Dance” (1940) and works for the James Weldon Thomas House. Dance and the music of the Savoy Club inspired much of his work, including “Rugcutters” (1930) and “Kolombwan” (1934). He also crafted several religious pieces, including a life-size statue of the Savior, “Come Unto Me“ (1947), commissioned by the St. Jude School in Montgomery, Alabama. In New York, Barthé also felt less confined in his sexuality. He crafted the homoerotic pieces “The Stevedore” (1937) and “Boy With a Flute” (1939). For reasons unclear, Barthé abandoned New York in 1949. He traveled with the wife of philanthropist Robert Lehman to her winter home in Jamaica, and shortly afterwards, he purchased an estate there, Iolaus. His time in Jamaica was unproductive. He tried to paint without success. He completed his two largest pieces, “Toussaint L’Ouvreture" (1952) and the equestrian “Dessaline" (1954), for the Haitian government’s sesquicentennial celebration, but he accomplished little else during his time in Jamaica. Iolaus was without power or telephone and his expatriate neighbors fled the hot and rainy summers. Loneliness and the slow pace of island life exacerbated an underlying depression. In 1961, he entered a hospital, first in Jamaica and then later in New York’s infamous Bellevue Hospital. Doctors diagnosed him with schizophrenia and he received shock treatment. He recovered enough to return to Jamaica but sold Iolaus in 1964. Unsure of where to turn, Barthé came home briefly, visiting his old teacher, Inez Labat. He received the keys to the city from then-Mayor Scafidi. Barthé spent several years in Florence, Italy, in the shadows of the Renaissance masters who had inspired his life’s work. Perhaps overwhelmed by the magnitude of Michelangelo, he could not work. He again became sick, and after a convalescence with friends in Lyon, France, arranged for return passage to the states. Penniless and ill, Barthé landed in Pasadena, California. He became the benefactor of patrons such as James Garner and Bill Cosby, although he ultimately sued the latter for casting statues without his permission. The City of Pasadena recognized the national treasure, and a street there is named for him. In the final photograph of the Vendryes biography, Barthé holds the street sign bearing his name. He smiles. Barthé died March 6, 1989, from complications related to cancer. St. Rose conducted a celebratory Mass and the bells rang in his honor. Barthés artistic legacy is complicated. Many African Americans disparage him as an “Uncle Tom,” for his many busts of famous men, including his last known piece, a bust of his patron, James Garner. He destroyed his most overtly political piece The Mother and may very well have destroyed Tortured Negro. He declined to permit the former to be displayed in the 1934 show, An Art Commentary on Lynching. The Creole Barthé was too high-minded, too formal for overtly political artists, such as Marcus Garvey. His formalism also set him apart from other modern sculptors. His work was too representational, too linked to the Renaissance to fit neatly among moderns such as Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. His harshest critics simply decry Barthé as an imitator, notable only for rising above the oppressive racism of his times. Vendryes, however, rightly notes that a Creole homosexual sculpting nude Africans and African-American models overtly challenged a white audience so fearful of African-American virility that they would (and often did) resort to violence to suppress it. Where Walter Anderson’s muse was the natural world and Ohr’s musen was pure form itself, Barthé reveled in the human body. He was not, as detractors argue, an apologist for whites in the separatist country of his birth. He longed for integration and advocated for it. However, politics was not his medium. It was the dancer, boxer, worker and the dying man. He treated them with dignity. Barthé, the artist said, “black is a color, not a race.” There is little remaining in Bay St. Louis to memorialize our greatest artist. A large pre-Katrina mural paying homage to the great artist was painted on the side of a county office building (on the corner of Second and Main Street), but the building was damaged by the storm and later demolished. The Bay St. Louis library houses a bust he gave to the city in 1964. Celestine Labat mentions a street off of Bookter named in his honor, but there is no Barthé or Barthe street found on the county’s Geoportal. Celestine Labat tells a story in Lori Gordon’s oral history. It is unclear when, but according to her, “Jimmy” Barthé was visiting one year at Christmas. A reveler came, and deep into his cups, the drunk man dropped and broke the plaster bust of Barthés first benefactor, Inez Labat. According to Labat, “We heard a crash from the parlor, and Barthé didn’t say anything, he just put his head in hands.” Years later, Celestine came into some money, and she sent Barthé the shards. He cast the piece, "La Mulatresse," in bronze and sent it to her, recouping only material costs and the foundry’s bill. Sources Vendryes, Margaret Rose, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture. University Press, 2008. Gordon, Lori K. “Oral History of Celestine Labat” Univ. of Southern Mississippi Oral History Project, 2003. Vertical Files, Hancock County Historical Society. Various Articles, Sun-Herald Archive. The Amistad Project. Tulane University. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed