Who to Believe?

|

|

I recently went shopping with friends to a number of our favorite thrift shops and found a long linen coat, a sweater, two shirts and three dresses. All of the items fit and I bought them.

For non-thrift store afficianados, the first piece of advice I have for you is to avoid shopping by size. You may miss some great buys that way. The coat I bought was a size 6, the sweater was a medium; one shirt was an XS, and the other a large. The first dress I bought was a 6, the second was a 2, and the third was a 0. Really? A zero? That is absurd. This is Deena Shoemaker. She is a teen counselor and a frustrated buyer of women’s clothing. These are the photos she posted on her Facebook page to illustrate a point. Clothing sizes make no sense. Her travails were written up the in Business Insider. |

Mind, Body, Spirit

|

How did we get in this predicament?

Before ready-to-wear, there was made-to-measure. Measurements were made, patterns cut and sewn, and clothing fitted. Who knew or cared what “size” they were? In 1939, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) began a yearlong study titled “Women’s Measurements for Garment and Pattern Construction.”

Working with the Bureau of Home Economics under a federal grant, they studied the weight and 58 body measurements of 14,698 women across seven states in the U.S. Once the final data was collated, statisticians analyzed the results and determined that five measurements were sufficient to determine the size and shape of a woman: weight, height, bust girth, waist girth and hip girth.

Weight was quickly dismissed as a measurement, analysts reasoning that “retail stores and homes frequently do not have scales and it is conceivable that women would object to telling their weights more than to giving, say, their bust measurements.”

Just a few of the biases included limiting the USDA study to white women, and the suggestion, after all the work was done, to recommend that mass manufacturers only produce every second clothing size. The study was completed in 1953 and published as “Commercial Standard (CS) 215-58.”

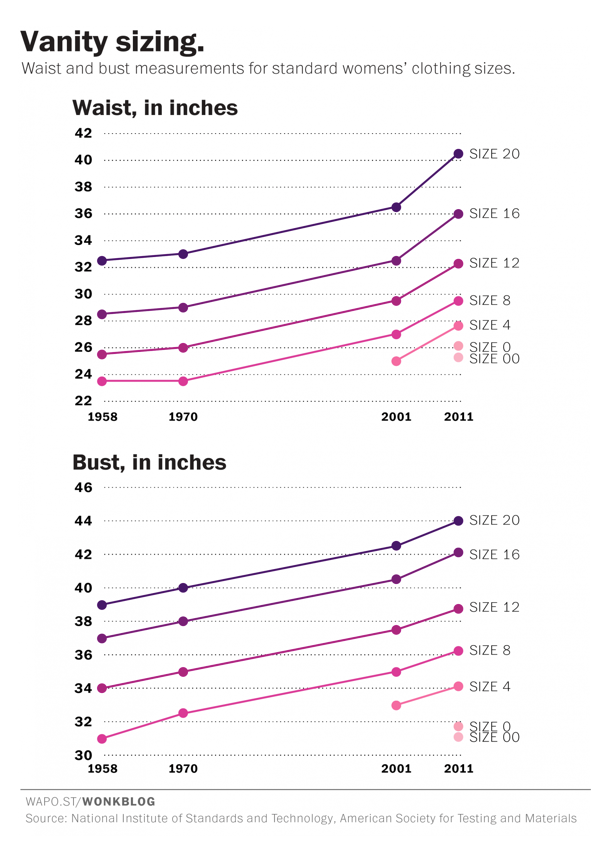

In 1970 the commercial standards were updated, partially in recognition that few women actually had an hourglass shape. In 1939 it was estimated that many women fit this mold, maybe due to restrictive undergarments, and now the percentage is about 8 percent. The new standards were voluntary for manufacturers.

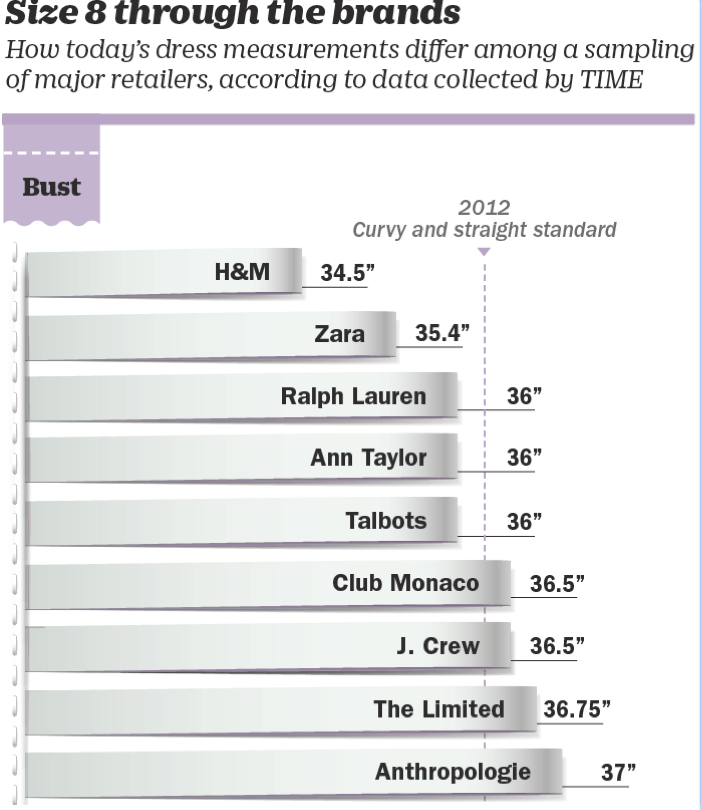

With no real restrictions, retailers were limited only by their imaginations, and garments started to be labeled with smaller sizes. By 1983 the voluntary standards were gone, and all that is left is size numbers.

Categories

All

15 Minutes

Across The Bridge

Aloha Diamondhead

Amtrak

Antiques

Architecture

Art

Arts Alive

Arts Locale

At Home In The Bay

Bay Bride

Bay Business

Bay Reads

Bay St. Louis

Beach To Bayou

Beach-to-bayou

Beautiful Things

Benefit

Big Buzz

Boats

Body+Mind+Spirit

Books

BSL Council Updates

BSL P&Z

Business

Business Buzz

Casting My Net

Civics

Coast Cuisine

Coast Lines Column

Day Tripping

Design

Diamondhead

DIY

Editors Notes

Education

Environment

Events

Fashion

Food

Friends Of The Animal Shelter

Good Neighbor

Grape Minds

Growing Up Downtown

Harbor Highlights

Health

History

Honor Roll

House And Garden

Legends And Legacies

Local Focal

Lodging

Mardi Gras

Mind+Body+Spirit

Mother Of Pearl

Murphy's Musical Notes

Music

Nature

Nature Notes

New Orleans

News

Noteworthy Women

Old Town Merchants

On The Shoofly

Parenting

Partner Spotlight

Pass Christian

Public Safety

Puppy-dog-tales

Rheta-grimsley-johnson

Science

Second Saturday

Shared History

Shared-history

Shelter-stars

Shoofly

Shore Thing Fishing Report

Sponsor Spotlight

Station-house-bsl

Talk Of The Town

The Eyes Have It

Tourism

Town Green

Town-green

Travel

Tying-the-knot

Video

Vintage-vignette

Vintage-vignette

Waveland

Weddings

Wellness

Window-shopping

Wines-and-dining

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

June 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

August 2014

January 2014

November 2013

August 2013

June 2013

March 2013

February 2013

December 2012

October 2012

September 2012

May 2012

March 2012

February 2012

December 2011

November 2011

October 2011

September 2011

August 2011

July 2011

June 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed