When writer/bookstore owner Scott Naugle begins to pack his library, he finds he's not the only book-lover to be transported by the task.

- by Scott Naugle

When the writing, fiction or nonfiction, connects with me at the deepest intellectual and emotional levels, often decades ago, so too does memory include the physical surroundings, the room, the chair, the palpable sense of reading that specific book.

A book is not read in a vacuum, but rather it is a sticky, intellectual syllabic immersion into the limbic region of the brain, where memory is stored, dense and nuanced with smell, touch, sight, and sounds.

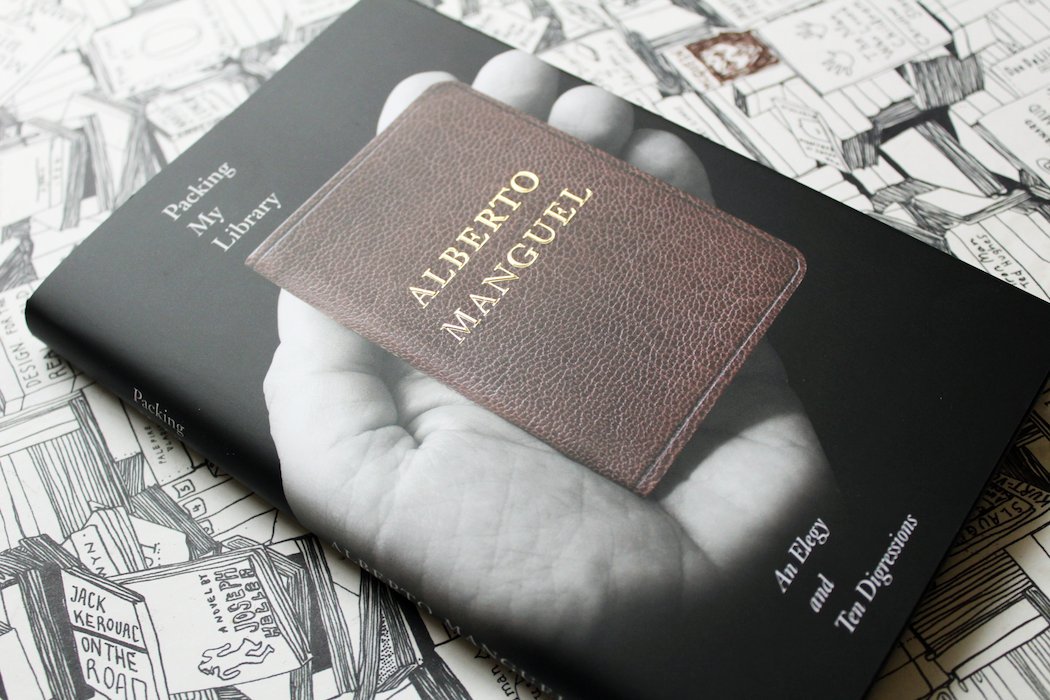

In Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions, Alberto Manguel notes a similar cognitive connection: “The books most valuable to me were private association copies, such as one of the earliest books I read, a 1930’s edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Many years later, memories of my childhood drifted back whenever I turned the yellowed pages.”

In the year 2000, Manguel and his partner purchased a medieval presbytery in the Poitou-Charentes region of France, renovating it into a personal library and home. In 2016, he was named director of the National Library in his native Argentina, necessitating the crating and moving of his extensive collection.

A few months ago, at an age when I should be downsizing rather than upsizing, we purchased a home, originally constructed in 1885, meticulously renovated to its original state, heart pine floors, beadboard ceilings, and white porcelain doorknobs, with, of course, the necessary 21st century upgrades including oversized bathrooms and a gas stove top (I’m staying away from the contraption) with enough jets to launch a small aircraft. Manguel writes elegantly and passionately about packing and shipping 35,000 books overseas. I only moved 5,000 books less than two miles down East Second Street in Pass Christian. I’m a minnow to his white whale.

To carefully box for the short journey, I pulled a four-volume set of Edgar Allan Poe from the shelf. It was already old and loose in its binding when I purchased it for a few dollars at a flea market over forty years ago.

“There are few persons who have not, at some period in their lives, amused themselves in retracing the steps by which particular conclusions of their own minds have been attained,” wrote Poe in The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Rereading it in the present, I was transported back to Somerset County, Pennsylvania, on a snowy January evening. Pushing midnight, I was sitting upright in bed on top of the tan and blood red striped bedspread in my bedroom, the fingers of the frigid winter air creeping in through the loose wooden window frame, rattling it when the snowy wind whooshed against it. The room was illuminated by the single bulb in my gooseneck reading lamp, casting menacing shadows on the far wall, as I turned the pages. Downstairs, the late local television news was droning on, the imperceptible words of the stern newscaster like a distant wailing. Again Poe, “Madmen are of some nation, and their language, however incoherent in its words, has always the coherence of syllabifaction.”

A few weeks ago, during our humid August, I packed several books by and about Toni Morrison. In The Bluest Eye, I had marked this passage, “Each night, without fail, she prayed for blue eyes. Fervently, for a year she had prayed. Although somewhat discouraged, she was not without hope”

I was transported to my study in Jackson, Mississippi, first reading this novel twenty-five years ago, sitting in a green leather recliner, the white Berber carpet contrasting sharply with the blue walls. Beignet, my small black poodle, was sleeping against me. It was a Sunday afternoon and I just finished several hours of working in the yard. The sun beamed through the double window at an angle with the effect that one half of my study was brightly lit while the other half remained in dusky blackness. It was as if a solid impenetrable line separated the two parts of the room into opposing worlds. Morrison’s use of language, the subtext, and how subtext overwrites a facile and simple interpretation of a story, captivated me. It was as if I was learning to read again for the first time. As Morrison explains in a series of essays, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, I would discover years later, “In other words, I began to rely on my knowledge of how books get written, how language arrives; my sense of how and why writers abandon or take on certain aspects of their project… of a kind of willful critical blindness.” From The Bluest Eye: “Outside, the March wind blew into the rip in her dress. She held her head down against the cold. But she could not hold it low enough to avoid seeing the snowflakes falling and dying on the pavement.” Every reading of this passage then and now is weighted with my guilt at not doing enough to destroy the unfairness thriving in our world.

I’m in the present, late October, relaxing for the first time in the upstairs library, early evening, in our new home. The two poodles, Gonzo and Snopes, are asleep. Glancing around the room, my eye snags every few seconds on a title, memories of how the book made me feel in a time and place of the past, how each informs my sense of self.

Jorge Luis Borges’ Collected Fictions rests behind me on a high shelf. From his short story The Library of Babel: “When it was announced that the Library contained all books, the first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure.” Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed