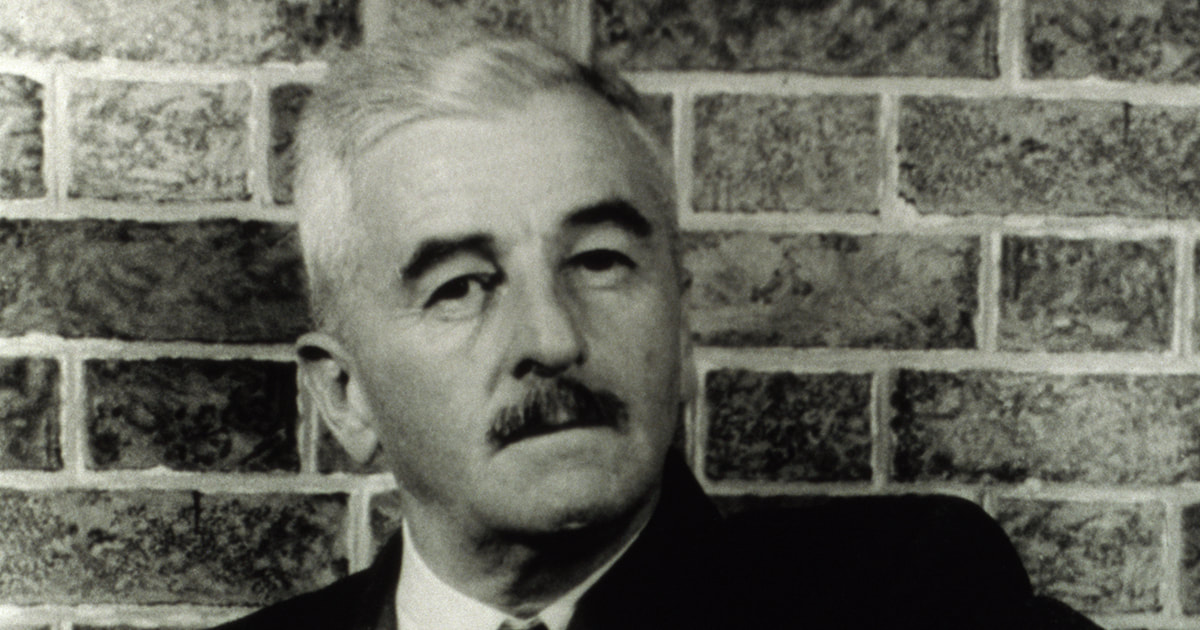

As a professor, writer Scott Naugle taught more than literary criticism; he allowed his students to read for the sheer joy of the written word - even Faulkner.

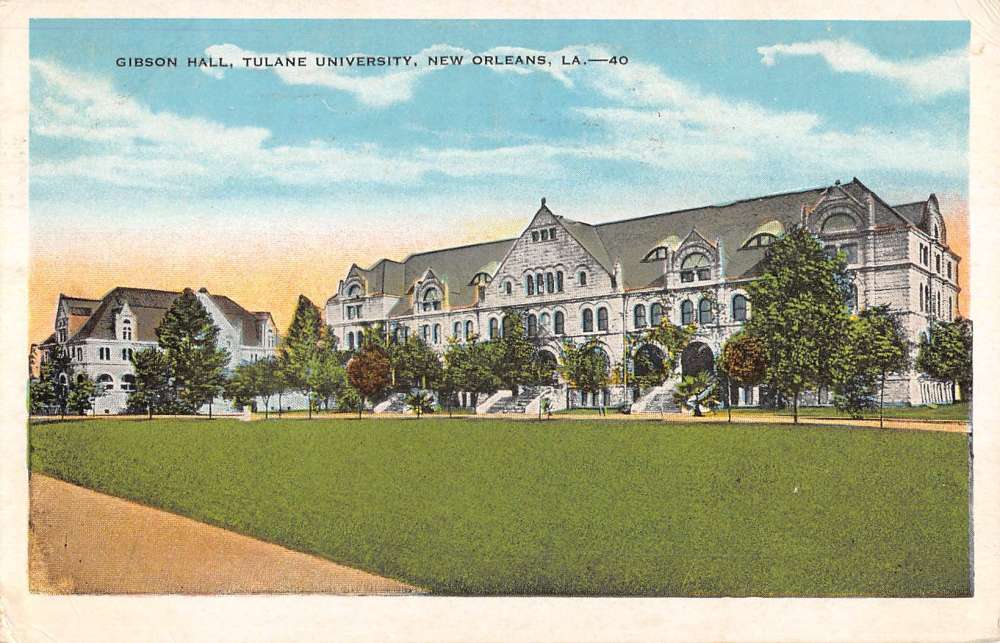

Through a clerical oversight, I’m sure, my “Reading the Modern South” class was scheduled in Gibson Hall. Gibson Hall faces St. Charles Avenue overlooking Audubon Park.

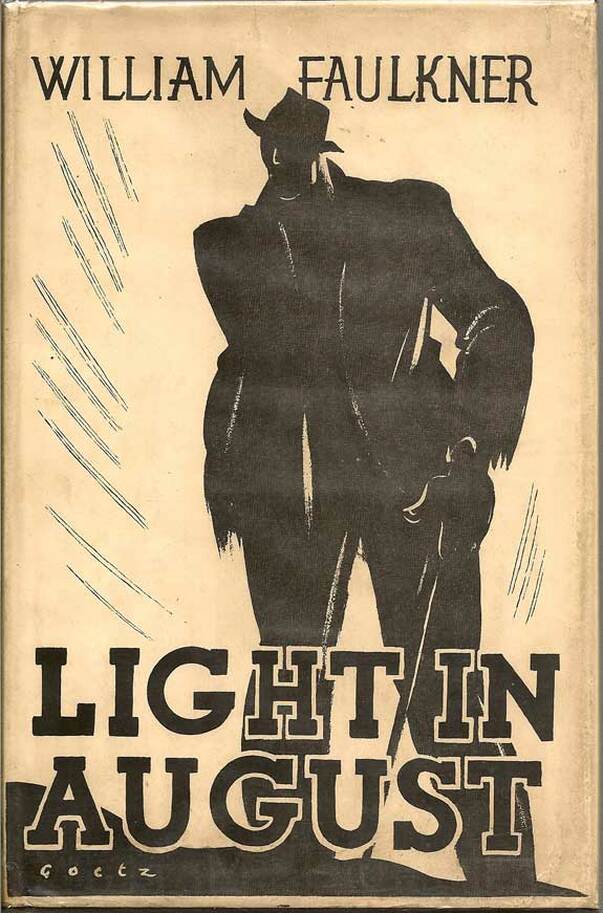

The oldest structure on campus, it was built in 1894 in the Richardsonian Romanesque style. Thousands of massive chiseled stones create an impressive façade exuding intellectual gravitas. The office of the university president and his staff occupy the lower floors of the building. The students arrived on time for the first class. Several carried clean, crisp notebooks while the remainder snapped open laptops. There was an almost equal number of men and women, nine in total, all either juniors or seniors, anxious survivors of the undergraduate milieu. We bantered a bit, I believed it important that they be relaxed with me, and then I handed around the course outline. Streetcars slid by outside the large windows, the clattering barely audible. Here is what I wrote in the syllabus and read aloud that evening: I commit to work with you in developing a set of critical analysis skills as you read literature. These skills include close reading, methods to critically analyze the text, comfort with literary vocabulary and terms, identification of historical and cultural issues, and several tools to interpret texts. You are encouraged to speak your mind in class and to write beautifully and convincingly in support of your thoughts. On that hot, humid night in early June as I discussed the course novels and supporting material we would read and write about, there was an audible group groan when I mentioned the inclusion of William Faulkner’s Light in August. Silence. And then I asked why. “We’ve read Faulkner in another class and the professor couldn’t explain the novel, but acted as if he could, and talked a lot. It was torture. No more Faulkner, please.” All shook their heads in agreement looking directly at me to gauge my response wondering, I assume, if they had crossed a line.

***

I experienced a flashback at that moment to two years earlier when I was a graduate student in a class on literary theory. We read Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, a beautiful and haunting novel if left unmolested by forced interpretations through various lenses of theoretical conjecture.

Literary theory attempts to offer avenues to understand a work of fiction through culture, historical forces, or the functioning of the psyche, among other approaches. Specific types of criticism include New Criticism, Structuralism, Deconstruction, Feminist Theory, and Marxism, among a salad of many others. The professor, let’s call him Dr. Wheezy, coached us each week to view Bronte’s work through a specific type of theory. It was Feminist Theory one week and then Cultural Materialism the next. Rather than enrich the reading of the novel, it became a series of weekly calisthenics in reductivism, marginalizing a beautiful work of literature into a constricted cardboard box. As an example, a weekly assigned reading was Terry Eagleton’s Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontes. The novelist Francine Prose, in Reading Like a Writer, recalls her experience in a graduate seminar as a student, “That was when literary academia split into warring camps of deconstructionists, Marxists, and so forth, all battling for the right to tell students that they were reading ‘texts’ in which ideas and politics trumped what the writer had actually written.” I vowed at that moment, should I ever be fortunate to teach, that I would work with students to read with delight, insight, and to marvel in the beauty of the written word.

***

In contemplating the syllabus for the course, my desire was to show different ideas and cultures within what is mistakenly perceived as a stagnant, singularly-minded South. We studied Thomas Hal Phillips’ The Bitterweed Path, about gay love in the mid-twentieth century rural South. Phillips was a closeted Mississippian and Republican political operative.

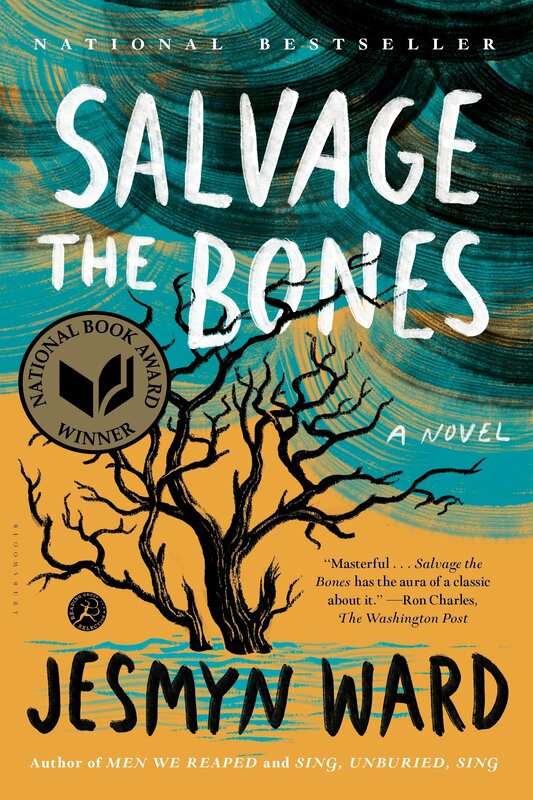

Uncle Tom’s Children by Richard Wright was included as a window into the hatred of the last century and the different, yet still as vigorous, forms it takes today. Shirley Ann Grau’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Keepers of the House was a springboard for discussion about our changing values and the hypocrisy of racism. To bring the readings into the present day, we read the marvelous Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning Salvage the Bones. I don’t know how and even if it is possible to measure success, but several students voluntarily wrote their end of semester research papers on Light in August. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed