No-Man's Land

The letters of one pioneer family who lived in west Hancock County in the late 1800s paint a vivid history of our rural county during the Civil War. Meet the Koches.

- by Marco Giardino, Ph.D.

Marco Giardino, Ph.D., is a retired archaeologist who worked with NASA at the Stennis Space Center in Hancock county, Mississippi. In that capacity, he has studied extensively the people and communities that preceded NASA's presence in the area. He makes his home in Bay St. Louis. Russell Guerin is a retired insurance executive who found new opportunity to pursue his passion for local history when he bought a home in Hancock County ten years ago. Having spent his summers there as a child and long weekends in his working years, he had become aware of the rich history of the area. His retirement made it possible to research the early settlers and their stories.  Click here to view on Amazon. Also available at Bay Books on Main Street, and the Hancock County Historical Society on Cue Street Click here to view on Amazon. Also available at Bay Books on Main Street, and the Hancock County Historical Society on Cue Street

Christian Koch was a prominent citizen of Logtown in the mid-1800s. He was a Danish Sea captain who first visited the area around Pearlington in the early 1830s. In his diary, Koch described Pearlington as a small, insignificant town, where the only trade was in wood and cotton with New Orleans. He commented that it was situated “in the midst of a large pine forest owned mostly by the government.”

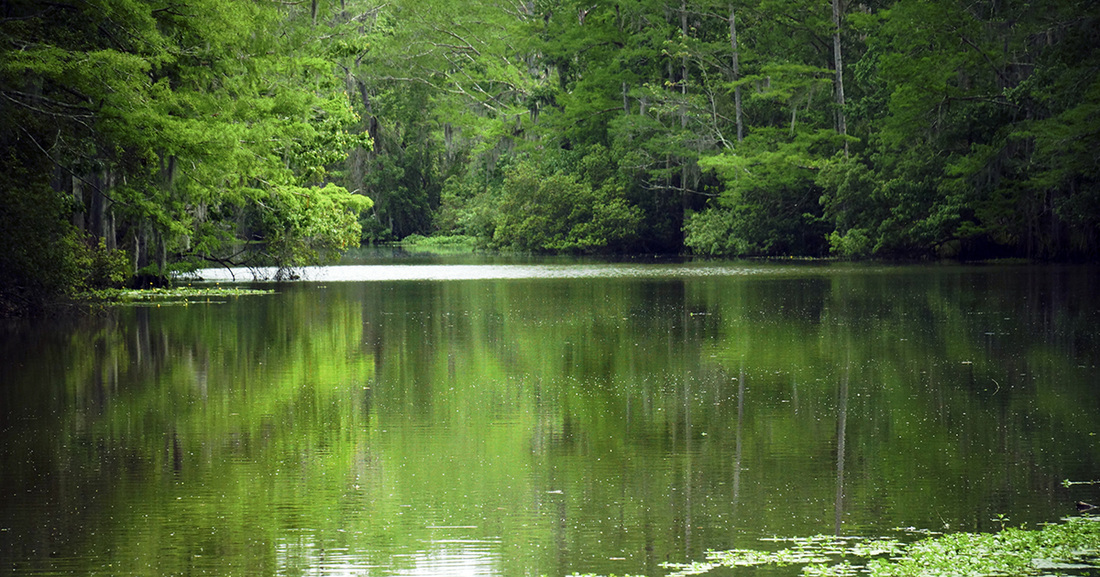

In 1841, Christian married Annette Netto of Bay St. Louis, and in 1854 they settled in Logtown, on Bogue Houma bayou, which bounds Logtown on the north. The Koches were letter writers. Hundreds of these letters covering a period from 1829 to 1883 are housed in the Hill Memorial Library at Louisiana State University. Many of these letters date from the Civil War, when Christian and his schooner, The Experiment, were embargoed by Union troops at Fort Pike while Annette struggled to raise their 12 children and to keep their Logtown farm running. Koch had no sympathy for the Confederate cause; in fact, in a letter from 1854, he noted that there was more liberty in Denmark than in the southern states. When Federals seized his schooner in 1862, he wrote to Annette that he expected $15 a day for its use. Despite working for the Union, he was often unable to get passes to breech blockades and visit his family in Logtown. The ugliness and hardship of the Civil War dominates the correspondence between the Koches. A letter from Annette to Christian from April 1863 describes conditions: “The Yankees burned all the schooners on Mulatto Bioue... There is talk that the government will take all the cattle, they put price down to 10 cents pound and if not ok, government will take anyway.” Annette continued to describe a litany of problems: merchants would not take Confederate dollars; trees were hard to find and birds caused corn to be replanted four times. She had tried unsuccessfully to forestall an infestation of worms by spraying pepper tea, and the hogs filled the place with fleas. Also of concern was the threat of conscription for their two oldest sons—Elers, 18, and Emil, 16. Christian wrote to Annette, September 10, 1862, saying, “If they [Confederates] have not yet taken Elers, send him for God’s sake... let him stay in the swamp with J. Parker.” Elers did end up fighting for the Confederates by early 1863. In April he wrote from Camp Johnson, in Lawrence County, Mississippi. “They are pretty strict here they make a fellow tow the mark they drill us from 2 to 6 hours a day on horseback, we have not got any tents only 4 tents in the company… We have enough for our horses to eat barely, when you write to me leave some blank paper for me to write back again.” Conditions were not better back home in Logtown. Annette wrote to Christian, who was still embargoed at Fort Pike, on April 21st and informed him that they had not had meat and coffee since he had left except for one sheep. She added that she had been trying to help (neighbor) “Old Jacks” by offering work. Annette, like many other citizens of Hancock County at that time, did all she could to assist those less fortunate. She wrote, “As long as he [Old Jacks] is here I will try to feed him and his family. They are poor, poor. Mary [his wife] looks like an old woman.” Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed