As the holidays draw near and infection rates break new records, the possibility of gifting the virus is a prospect we can avoid.

- by Ellis Anderson

The Mississippi Department of Health/University of MS Medical Center now offer free statewide drive-thru Covid testing. You do not need a doctor's referral. To qualify, you need to have some Covid symptoms or been exposed.

It's extremely simple to make an appointment through their online system! Click here. Want to see a snapshot of how your Mississippi county has fared with infection rates over time? Click here.

The five words of the text message captured a sense of urgency: “Please call me, it’s important.”

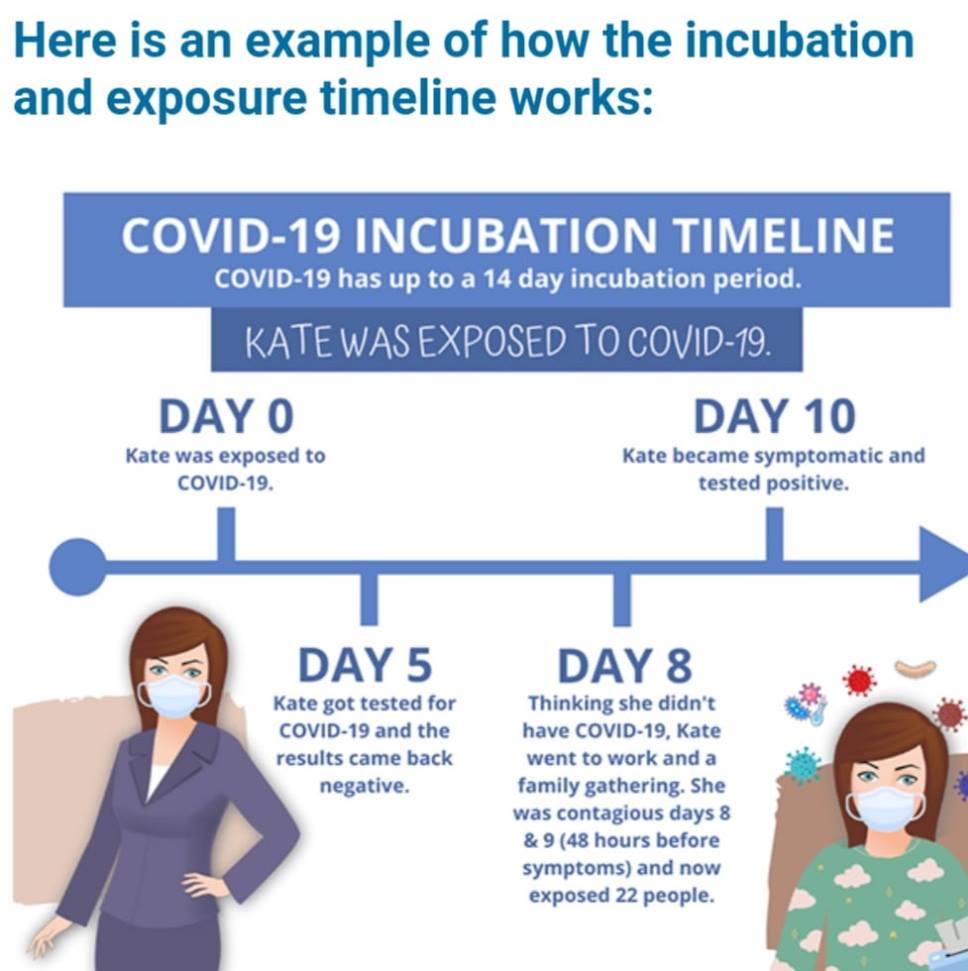

I texted my colleague/friend back, telling him I was on a tight deadline and asking if I could call him in a few hours, around 10 am. My anxiety ratcheted up when his reply popped right back. “This can’t wait. Please call.” In the moments before he answered, my mind conjured up several work-related scenarios, so I wasn’t expecting his first sentence. “I’ve just got the test results back and I have Covid.” My friend went on to explain that he wasn’t experiencing any symptoms. He’d only gotten tested after his partner hadn’t been feeling well and tested positive. He was performing his own contact tracing and thought he should let me know. I flipped back through my calendar and saw that our meeting had been 12 days before, which eased my mind somewhat. Then my friend pointed out it was impossible to pinpoint how long he’d been infected. I thought back over our meeting. We’d walked through the neighborhood then had an early dinner at a local restaurant. It had been a chilly, breezy evening. We had debated on eating inside, but stuck with our resolution to get an outside table. We’d spent a good two-hours there with our masks off, catching up and going over projects. I understood in that moment how many people’s lives may have hinged on that one little, seemingly minor decision on where to sit.

Now, it was possible that I had unknowingly infected my husband, in his 70s. And the business associates he had come in contact with during the past week.

Wait. What about the dear friend who met me for lunch, the first time we’d had a good visit in many months? We’d also eaten at an outdoor table, but had we lingered too long? Stood too closely together when I walked her to her car? What about the people at the small dinner party she attended a few days later? Oh, and there was my doctor’s appointment. The grocery store trip. The pharmacy. I’d worn a mask for all the visits, but would it have been enough if I’d actually had Covid? It dawned on me that I could inadvertently be a super-spreader.

Several trained National Guardsmen and a nurse were manning the station. I discovered I should have made an appointment online beforehand, but the kindly nurse did it for me on her own phone.

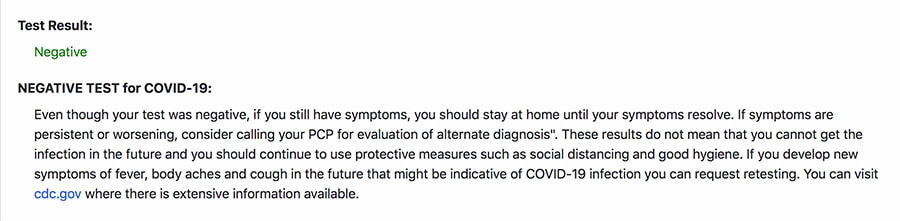

The entire process took less than 30 minutes. I pulled my car up to the testing table and two masked/face shield-wearing guardsmen with disposable gowns and gloves approached the car. One carefully explained the process. The guardsman wasn't a health care worker, but had been specially trained to perform the tests. He wore a mask and face shield and was suited up with paper scrubs pulled over his camouflage uniform. I’d be given two tests. One was a rapid result and afterward I could pull into the parking lot to wait and learn the results within 15 minutes. The second test is called a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test. I was told the state would email me results from this more accurate test within two to five days. Here’s why they give two: the rapid test is highly accurate if you test positive. However, if you test negative, you still might have the virus, because the rapid test is more likely to give a false negative. That’s why a PCR test is also administered. It detects the virus’s genetic material. The guardsman giving the tests then explained that the rapid test uses a nasal swab, but it doesn’t have to be inserted very deeply. He truthfully told me that the second test – the PCR – was "uncomfortable" for most people because it had to be inserted more deeply into your nasal cavity. He warned me that I might want to cough as a response. He was completely accurate. The first test was a breeze. I pulled down my mask and it was administered through my car window. The second test didn’t cross the line into painful, but I felt extremely “uncomfortable” for a few moments. When I reflexively started pulling my head back, the guardsman coached me to hang in there and the sample was obtained. My sinuses stung for about five minutes afterward. I pulled into a parking space and after a quarter hour, the nurse approached with my rapid results. “Negative.” I hadn’t even realized how tense I’d been until she said the word. She also stressed that there was a small chance that it might be a false negative. I should still self-quarantine until the more accurate PCR test results came back. Since this was a Thursday, she guessed the results would arrive in my in-box on Monday. However, the PCR test results arrived on Saturday morning, only two days later. Another negative. I was thrilled, as were my husband and my friend. My colleague’s relief came through on the text, “GREAT NEWS!” he wrote. I tried to imagine how I would have felt in his position, knowing that I might be the unknowing cause of someone else’s illness.

My experience underscores the reason the current spike has already overtaken the initial pandemic rates. Americans have grown weary of the limiting precautions. Yes, the percentage of deaths has fallen as the medical community has developed better and more treatment options. But the exponential increase in the infection rate is overcrowding hospitals, overworking health-care workers and making critical medical care less available for people with other major health issues.

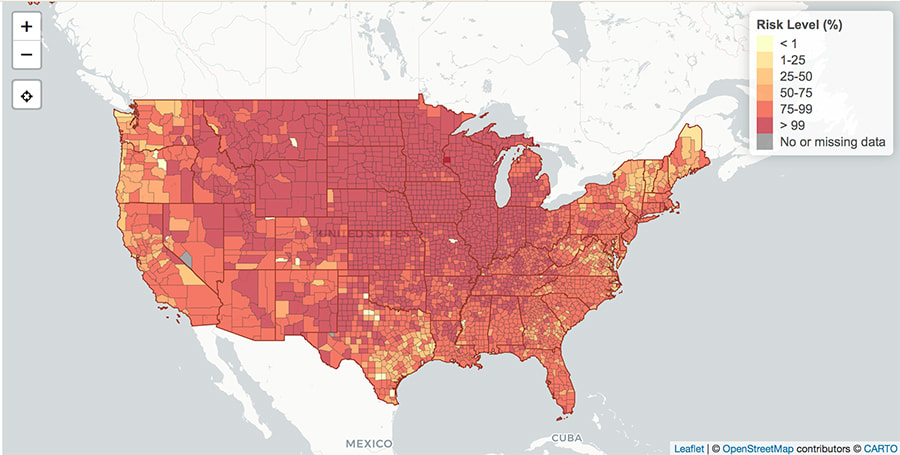

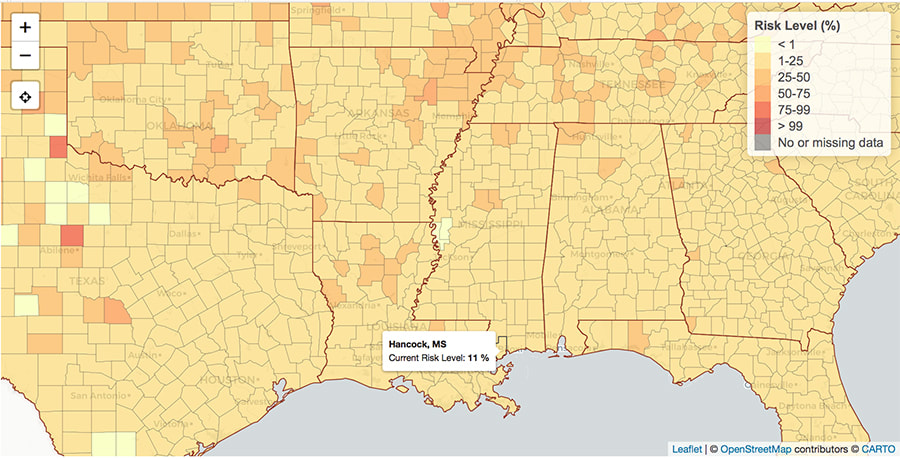

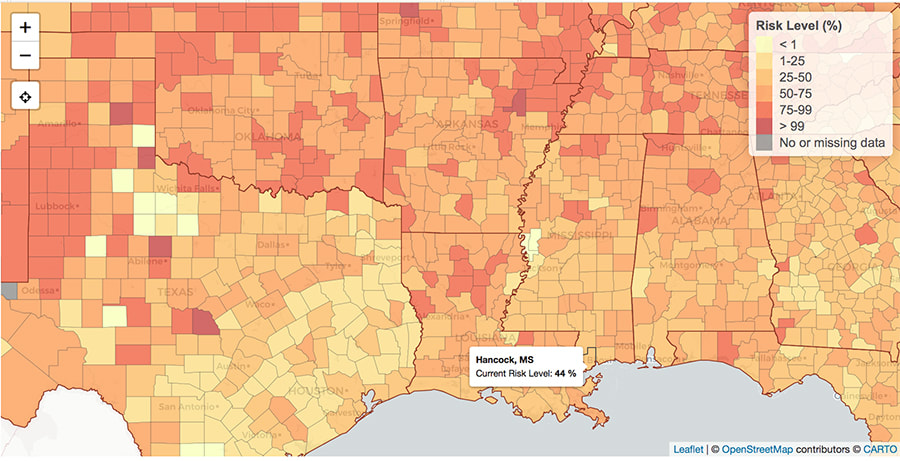

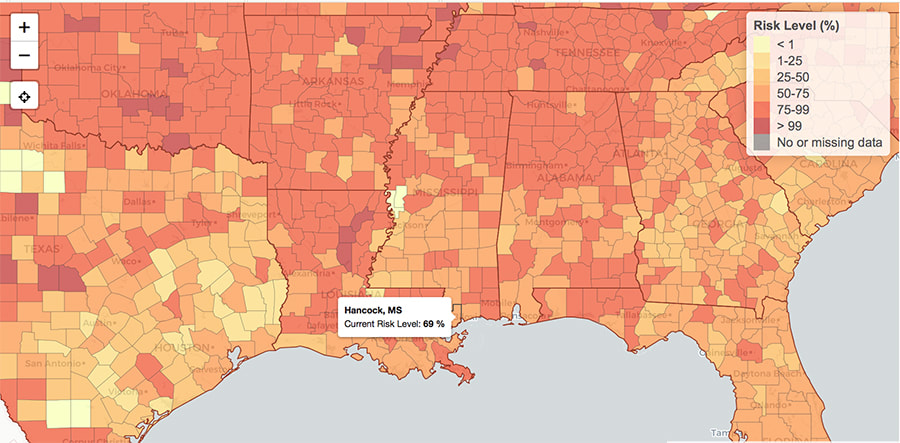

We know all that. We hear it daily. And mostly tune it out. Yet, if we as a country don’t make major behavioral changes, the approaching holidays could become doomsdays. The natural human yearning for contact - especially with those we love most - tempts us to ignore precautions. Throw in increased alcohol consumption that lowers our inhibitions and we have a Covid powder-keg. Here’s a sobering tool that can help you make plans in the upcoming months: to understand what personal risk you’re taking for a holiday gathering, this “Risk Assessment Planning Tool” by Georgia Institute of Technology is indispensable. The map allows viewers to look at every US county and see what the chances are that someone with Covid will be attending an event. The map is constantly updated, based on the most recent Covid reports. "This map shows the risk level of attending an event, given the event size and location.

The map also allows visitors to set the size of the gathering – you can choose 10, 15, 25, 50, 100, 500, 1000 and 5000. When the settings are placed at 100 guests, the national map looks red-hot.

Right now, throughout the Midwest, a majority of counties have an over 99% chance that someone will have Covid at a gathering of more than 100. Lower the setting to 50 guests and there’s still a 50 – 75% chance in much of the country.

After my first real brush with the virus, I’ve come away more determined to be more vigilant with masking, distancing and meetings. I'll weigh the risks before attending events.

While I might feel my chances of survival are good if I catch Covid, I understand that I could be responsible – unintentionally, unknowingly – of infecting others who won’t fare as well, those who might be hospitalized or even die. And some of these might be the most meaningful folks in my life. Will those people blame me? Probably not. The question is whether I’ll be able to forgive myself. One of the most comprehensive COVID resources is WorldOMeter.com. It has lots of columns that allow you to see where your state stands in infection rates, testing and deaths.Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed