In the century since it'd been constructed, the building had served as a school, a community center and a place for healing broken lives. But no one had ever called it "home."

- by Ellis Anderson

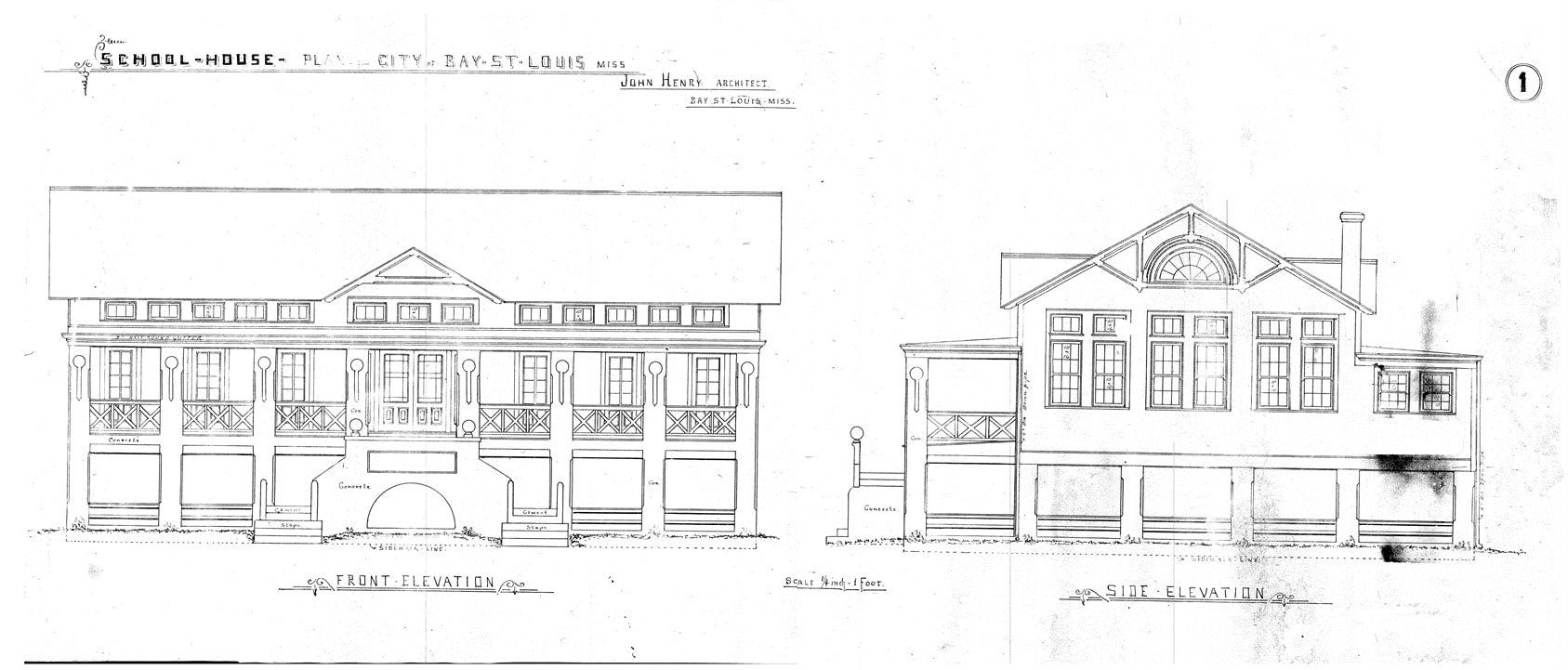

Like the day I first saw Webb School. Biking up Citizen from the beach, at the second stop sign, I came to a dead halt. The white building across the intersection seemed more windows and porches than walls. It looked like some decrepit West Indies plantation house, with the main living area on the second floor. Eight windowed doors opened up onto the deep veranda. How had it landed in this neighborhood of modest historic cottages and ‘60s ranch style homes?

The white building beckoned me onto the property, and I stood under the boughs of three giant oaks looking up at it. After a while, it became clear the place hadn’t been built as a house. It had a civic feel to it. Maybe a city hall? A school? On the concrete facing to the front steps, “Rebos” had been painted in bright blue. The place seemed abandoned, so I walked up the front steps. Curtains blocked the windows on doors, so I couldn't see in to confirm. I biked back to Main Street, and began asking my neighbors. Yes. It’d been an elementary school, built in 1913. Starting in the 1960s, it’d become a community center of sorts, with city offices, and space for programs like scouting and art classes. In the early ‘90s, it’d been bought by a non-profit that used it for 12-step group meetings. Everyone had started calling it Rebos House. Those in the know explained that Rebos was “sober” spelled backwards.

I biked over often after that, approaching from either the Depot or the beach, my heart lifting a bit whenever the school came into view. I had carved out a small efficiency in the gallery building on Main, but in a few years I planned to buy a real home in Bay St. Louis. Something historic. A place that I could lavish with love for the rest of my life.

But the school didn’t seem logical. Even if I could scrape together the money to buy the building, I’d done enough renovation projects in New Orleans to know the scope of this one would be gargantuan. I’d be going it alone since I was single. And a working artist. It’s a career path that demands nerves of steel. Graph an artist’s income and it usually resembles the path of a bungee jump. Off a very high bridge. The years passed. Offers I made on other houses in the Bay didn’t go through for one reason or the other. But in 2002, when I heard that Rebos House might be coming up for sale, instead of approaching the owners and making an offer myself, I tried to persuade a friend of mine to buy it. By that time I’d turned 45 and some common sense was finally starting to take root. When my friend passed on Rebos, a wild idea took hold in my mind. It grew rampantly overnight like a jack-in-the-beanstalk seedling, feeding off my longtime dream like Miracle-Gro. Overnight, the thick leaves of possibility smothered the straight new shoots of sensibility I’d been nurturing. Still, I called my long-time accountant in the morning. “I know it’s crazy, but I want to make an offer on that place,” I said. I expected Gina to talk me off the cliff. Instead, she pushed. “You drove me by there eight years ago and told me that building was going to be your home someday. You gotta do it.” So I made an offer. The non-profit’s board accepted. I shook in my boots. I drove my old boyfriend by to see the vast, ramshackled building. “Aren’t you glad we’re not together anymore?” I asked after a quick tour. I was joking. “Hell, yes!” he said, not joking at all.

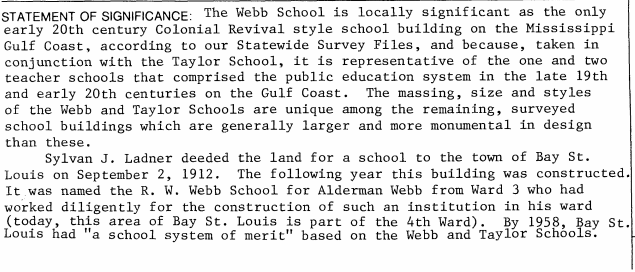

The Rebos board cautioned me that the building had some deed restrictions, something to do with "historic stuff." They didn’t know exactly what. So I rooted around in the courthouse to find details. I discovered the building’s original name, Webb School. The deed had terms I didn’t understand. Designated Historic Landmark. Permanent Easement.

I decided to call Mississippi Department of Archives and History and find out more before the closing the following week. But I’d be cagey. I wouldn’t let them know what building I was buying. After all, I might not want state officials looking over my shoulder during the renovation, right? I didn't yet understand their job as stewards of the irreplaceable assets of the state. After a few pass-alongs, I was connected to a man named Richard Cawthon. I introduced myself. “I’ve got a contract to buy a historic building on the coast, and the deed says it’s a Historic Landmark. What does that mean exactly?” I said. “Which one is it?” Cawthon asked, not bothering with pleasantries. Nervous suddenly, I hedged. “Uh, I’d rather not say right now. But it’s somewhere in Hancock County.” “That means it’s one of five buildings,” Cawthon said without pause. “It’s either the courthouse or the train depot, the Second Street School, the Old City Hall or Webb School. Which is it? I presume you’re not buying the courthouse.” Busted. I came clean. I found out that a Landmark is the highest architectural designation that can be bestowed by the state. At the time, there were only about 500 in the entire state. The program works to save the most important buildings for future generations of Mississippians as part of our shared heritage. The designation came with restrictions. Mississipppi Department of Archives and History even has a say with what happens to the inside of landmarks. Every major change would have to go through the state for consideration. “Will you allow me to make the interior changes needed to make it livable as a house?” I asked. I was told I’d have to submit scale drawings. The Mississippi Landmarks board would approve or deny. Although they only met once a month, I was in luck. The next board meeting was in three days. The closing was the following week. And I couldn't close on a building I couldn't make into a home. That gave me seventy-two hours to come up with plans. I wasn’t married to an architect then. So I took a tape measure to the school and measured and imagined and drew up sketches on graph paper I normally used to design jewelry. Those days are a blur now, I didn’t sleep much.

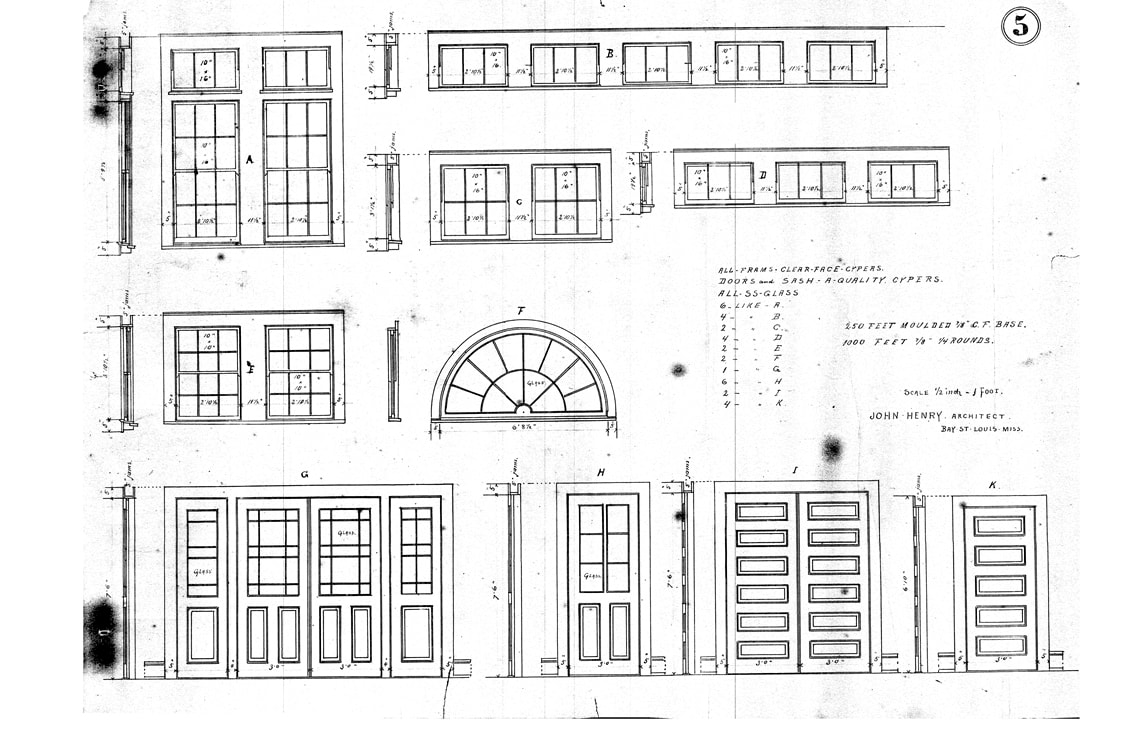

The MDAH guidelines stated that they wanted the character of the building to remain intact. Chopping the space up by creating lots of permanent interior walls was forbidden. I'd learn later, after architect Larry Jaubert became my husband, how much of a wonder Webb School is. The ingenious architect John Henry had used a support system that made the building incredibly strong without walls or columns to break up the huge, high-ceilinged classrooms.

So I sat in the middle of those old schoolrooms at Webb for hours and tried to listen. It was a happy building, generations of children’s laughter and song embedded in the walls. A lot of the windows were boarded over, but the light still was magnificent. Why would I want to change that? Why would I try to remake it into the average suburban house? On my sketchpad, the two grand classrooms became two large apartments. I'd live in one and rent out the other. The two cloakrooms in the back became kitchens. The central hall, a library accessible from my side. The former schoolrooms would become loft-style living areas – with plenty of room on each side for dining, living and and a partitioned off bedroom area. On the morning of the meeting in Jackson, I faxed several graph paper sheets of scale drawings to the MDAH office. I knew the board would be expecting formal architectural renderings. I imagined them snickering at my amateur efforts and then shaking their heads. I saw the eye-rolls. I imagined the different ways they’d tell me “no.” But since they’d been gracious thus far, I guessed they’d at least be polite about rejecting my plans. The call came finally. “We voted. It was unanimous,” the official said. I sighed with disappointment. On some level, I’d known it all along. “Yes,” he said. “We all voted yes.” to be continued.... Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed