What's in the Water?

by Janet Densmore -

The waters off our beaches are monitored weekly by MDEQ for certain bacteria. You'll learn why and also find out how to check water reports with your smartphone - before you swim.

You have likely noticed the signs depicting a graphic outline of a swimmer on a post next to the beach sidewalk that links our two towns. There are 4 stations posted along the beach in Waveland and Bay St. Louis; there's another one on Henderson Point in Pass Christian too, and all along the Mississippi coast.  painting by Janet Densmore, author of this article painting by Janet Densmore, author of this article

These are sampling stations with graphic indicators of when it is safe to swim and when it may not be the wisest choice. If you see the sign card depicting the graphic of a swimmer with a red strike line across it - don't panic, this is meant as a warning and does NOT mean you will fall ill or be poisoned.

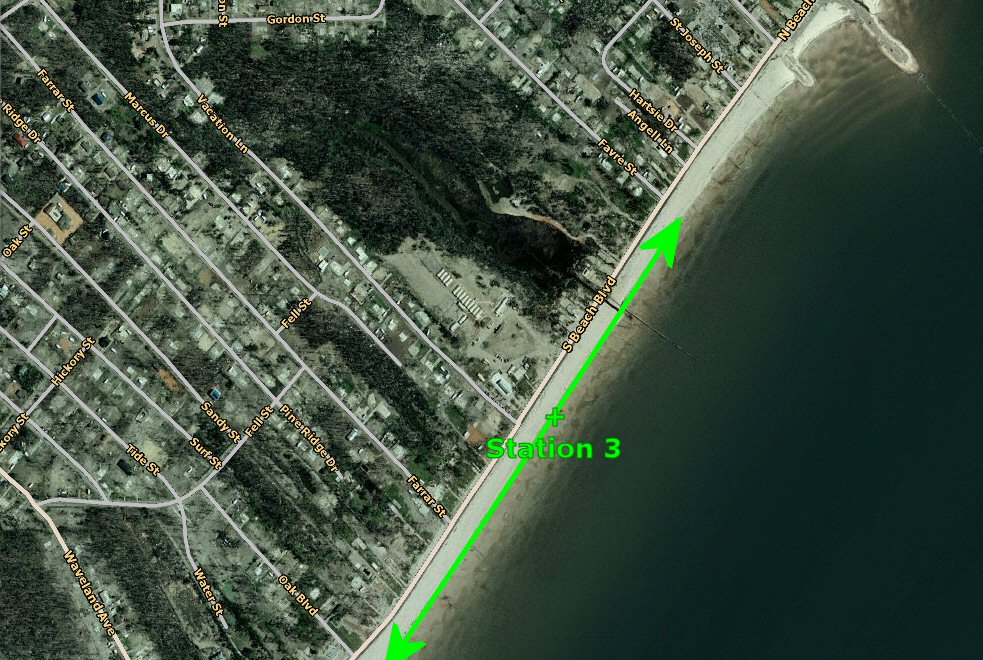

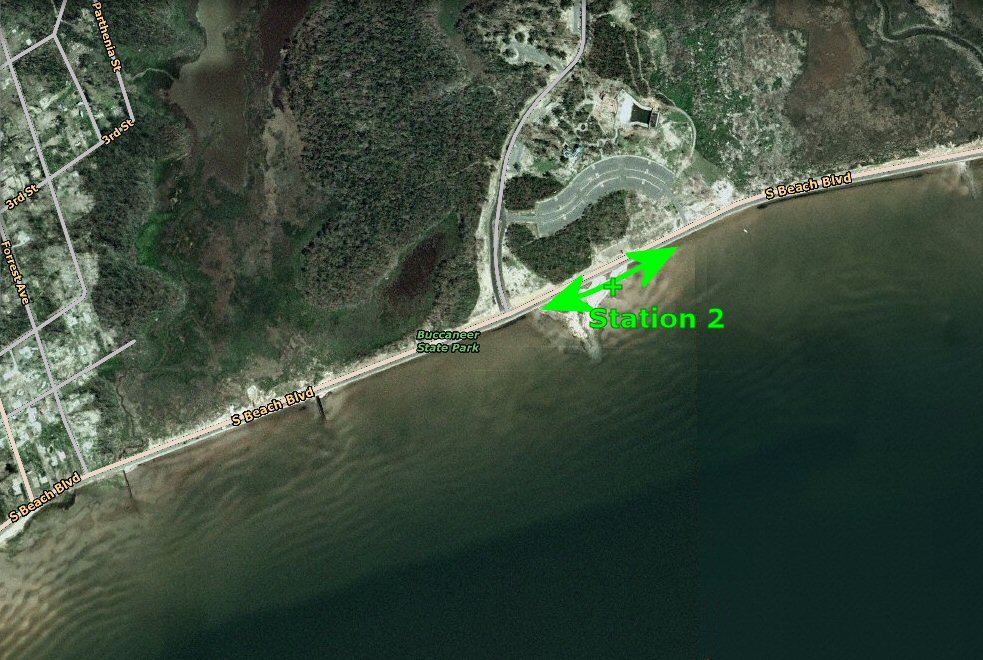

You will find the monitor signs posted in the following locations: Tier 1 is on Lakeshore Drive; Tier 2 is at Buccaneer State Park Beach near State Park Road; Tier 3 is near Vacation Lane / St. Clare Catholic Church; Tier 4 is near St. Charles Street, Bay St. Louis. Editor's note: See maps at end of this article. The Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality monitors the beach water at these sites to keep us safe from biological pollutants, namely bacteria and viruses. Easy to remember is a standing notice from DEQ recommending that "swimming not occur during or within 24 hours of a significant rainfall event." A "significant event is 1-inch or more rain." Runoff from storm drains with this amount of rainfall automatically triggers a warning because more bacteria spill into the beach waters mostly from animal waste or failed septic systems. After 24 hours of sunshine and UV radiation, bacteria dissipate back to the safe range. I spoke with Emily Cotton from DEQ who broke it down for me. Cotton explained that DEQ's Beach Task Force tests our shoreline at the monitoring stations weekly year round. What exactly do they test for? Indicator bacteria. These are benign bacteria called enterococci (enterococcus if singular) who are always present in the water.

Much like the canaries in the coal mine, these little guys are a signal of water conditions which are favorable to other bacteria/viruses which you might not want to encounter. The bad guys are also always present in the water, but not in large enough numbers to bother about most of the time - like stingrays or sharks. Beach monitoring of enterococci indicates when conditions are ripe for greater concentrations of the bad guy viruses and bacteria. So who are they and how do we best protect ourselves from them?

On the short list: the vibrio family of organisms and parahemoliticus found on raw oysters can be nasty. Emily Cotton reminds me that certain groups of people are also most vulnerable: toddlers and people who have weakened immune systems, and we should always be mindlful to protect the vulnerable among us. On the positive side, there are some good vibrio creatures who eat up oil - we love that idea. When dispersants broke down BP's massive oil spill into small droplets throughout the water column of the Mississippi Sound the vibrios multiplied- the good ones and the bad ones. There's vibrio cholera causing havoc in third world countries with poor sanitation like Haiti and India. We don't have a problem with cholera stateside. In Mississippi, (Louisiana, and Alabama) you may recall warnings not to pick up tar balls because of vibrio vulnificus - the worst bad guy of the vibrio family. The vulnificus is more commonly known as the "flesh eating" bacteria. Maybe you have read news stories of people who become infected and with vulnificus. Fishermen sometimes fall prey to such attacks. Any wound that breaks the skin opens the door to vibrio vulnificus (and any other bacteria/virus) when concentrations of these organisms are high. That's why the beach monitoring program helps protect us.

There are all kinds of bacteria - e-coli for example - present in the water. These become dangerous only when higher concentrations of them are present. Sample rates over 104 show an increased risk for illness at a rate which might translate something like this: Of 10,000 bathers 36 people might actually get sick. How sick? More than likely, a little stomach trouble or diarrhea, which would be over fairly soon.

For little kids and people with weakened immune systems the story is a bit different. For instance, if you eat a raw oyster with parahemoliticus and you're healthy, you'll probably be fine. However, if your constitution is impaired - you may be sickened enough to die. This is why doctors warn people with certain illnesses, vulnerabilities, or undergoing certain treatment regimens to avoid eating raw oysters entirely, thus preventing any potential of risk. Or you could cook them first. As for the bad vibrio vulnificus, fortunately, doctors along southern beaches are onto this one, but diagnosis is difficult. These guys are hard to test for. So what does one do about a scratch at the beach, or a prick from fish or crab? Good old soap and water! Remarkably, Emily Cotton told me, the anti-bacterial gels, hand sanitizers and sprays will go after bacteria but are not as effective against all viruses. To kill both viruses and bacteria, good old soap and water is your best bet. If you get a wound, clean it right away with soap and water. Don't go in the water during warning days if you have an open cut or sore.

Finally, if you have been in or on the water recently and you have a wound that turns red (indicating infection) be vigilant. Any red line extending out from that wound, any fever, means you should seek medical attention immediately, particularly when the warnings from DEQ are in effect. Things can go bad quickly with these organisms.

When I checked the DEQ websites' historical data I found the last warning about high concentrations of sentinel bacteria for our beaches was on February 6-10 of 2015 for Waveland Beach near Vacation Lane extending from Oak Blvd. eastward to Favre Street. The year before, (2014) from April 18 to May 7 there was a warning near St. Charles Street from the box culvert eastward to Ballantine Street, as well as Long Beach near Trautman Ave. from Oak Gardens Ave. eastward to S. Girard Ave. To make it easy to find out: you can have beach advisories sent directly to your email or you may text "MDEQbeach" to 95577 to receive beach advisories by text to your cell phone. Of course you may always check the website at: www.deq.state.ms.us; you will find links with MDEQ on Facebook and you may follow on Twitter as well. In the interest of full disclosure, this author has been known to go kayaking and swimming at Waveland beach only to discover later that the red line across the graphic swimmer on the monitoring sign warned against it - and absolutely nothing bad happened to me. I hope this information has encouraged you to know that our beach is safe and we can always check to be sure of it. Hancock County Beach Monitoring Areas

Click on maps for larger versions on the MDEQ site!

This article is based on information gathered from various governmental resources. It is written in good faith to make the general public more aware of monitoring methods and signage. It is not meant to be a full guide to bacteria that may be present in gulf waters. Please see the MDEQ site for more details. If this sounds like a disclaimer, that's because it is.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed