In the writer's open letter to the author of this compelling book, he explains why he cannot review it.

- story by Scott Naugle, photos by Patrick O'Connor

Dearest Margaret,

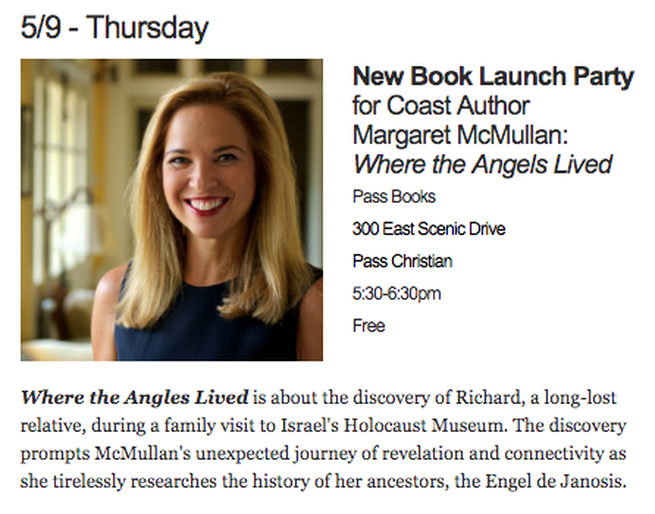

It was almost fifteen years ago that I first reviewed and wrote about one of your books, “How I Found the Strong,” for a literary magazine. Your family’s history, on your father’s side, was the impetus for the young adult novel. While we were friends at the time, we’ve become closer. I consider your family an extended family – your mother Madeleine, husband Pat, and your son James, whom I still can’t believe the years have passed so quickly that he is graduating from college next weekend. You’ve hung up on me during phone conversations and slapped a cellphone out of my hand when I was texting and driving (you were right to do this, even underscoring it with adult language). For these reasons, I struggled with whether I would have the professional distance to review and discuss “Where the Angels Lived”. How could I pass judgement on the intensely personal and compelling work of a close friend? Transparency is always the correct approach, so if I am asked to review your most recent work, I’ll be transparent about our long friendship. I wanted you to know this. Your love for your family, past and present, and their histories appear to be a consistent motivation for your intellectual work. “How I Found the Strong” was inspired by a long-lost manuscript, “The Life and Times of Frank Russell.” Frank Russell was the great-uncle of your grandmother on the McMullan side and dictated his remembrances of life in Smith County, Mississippi. As you recollected in the novel’s afterword, “the part of Frank’s story that interested me the most, however, was what he did not talk about.” A historical detective, you used the facts at hand and created the story of the young fictionalized Frank Russell into an award-winning novel. A few years later, in 2008, you visited the Holocaust Museum and learned of a relative you had never heard of – “Richárd.” The museum archivist looked at you and declared, “Look at me, you are the first to ask about him. Do you understand? No one has ever asked about this man, your relative, Richárd. No one ever printed out his name. You are responsible now. You must remember him in order to honor him.” As the curious and impassioned intellectual I know you to be, you had no choice but to learn more about Richárd Engel de Jánosi. Like the nonfiction manuscript of Frank Russell that you spun into a beautiful novel, you were presented again with a previously unknown, and hidden, piece of your family’s history. The story of Richárd Engel de Jánosi is so incredible, though, that a nonfiction exhumation of your family’s story through research is the appropriate platform. Life is stranger, and far more brutal, than fiction. But against what may be the safe or prudent thing to do, in a Hungary that remains deeply anti-Semitic, you traveled to ask questions about a Jewish uncle that you never knew existed nor was ever acknowledged in any way. You met resistance, both official and subtle. As I turned the pages of the advance copy of “Where the Angels Lived” that you were kind enough to give me a few months ago, I feared for your safety. As you recollect in “Where the Angels Lived”, “Never heard of him,” your mother snaps when you ask about Richard. “You must have it wrong. I don’t have time for this.” Madeleine McMullan hangs up.

Richárd was the son of your great-grandfather, Adolf, as your research in Hungary revealed. Adolf created a vast business empire of land-holdings, lumber, and coal by his mid-thirties. He started without a penny and succeeded despite the anti-Jewish legislation in Hungary. He had to pay “tolerance taxes.” You speculate, “Maybe he was granted immunity as a Jew because he took such good care of his mostly Catholic workers. He built them homes, schools, bathhouses, and churches. He paid for their teachers and priests.”

All of this began to fall apart in the years leading up to 1944. And while many members of the Engel de Jánosi family sent their money to Swiss bank accounts, converted to Catholicism, changed their names, or took the opportunity to leave the country early, Richárd, strong and quietly defiant, resisted. One of the most beautiful passages in your book is when you use your considerable talents as a novelist to bring Richárd to life for us from the few facts about him: “He looks to be the kind of relative I would have loved – tall, distant, cool. The quiet type, pensive and precise. I would have tried to make him laugh… He looks so sure of himself, even a little defiant, stubborn. Maybe too proud. Maybe he believed too much in his own decency, maybe that’s what got him killed.” What you later learn is that your mother, at the age of ten in April 1939, was spirited from Hofzeile, the family estate, at night with her mother, your grandmother, Carlette. “My mother wore a dark blue coat several sizes too big so that she could grow in to it. My mother had the red measles, which had spread into her eyes. [My grandmother] told my mother not to look back, to never look back.”

Later, as the train was stopped at the border crossing, “the German fear of germs” prevented the officers who boarded the train from entering the cabin where your mother suffered. “Carlette slid the papers under the door… They kept their gloves on… held the documents at the corners” and quickly stamped them.

Learning all of this was too much for you. Against your grandmother’s advice to your mother eighty years ago, you had looked back. “Sitting there in the pew carved of Moravian oak, I start to shake. I curse every last Hungarian who deported or murdered my family. See, Look at me. My mother got out and she had me and I had a son. You didn’t end us.” Richárd, as you learned, stayed and administered the family businesses until he was met at his front door “by a black car with swastikas on the doors.” He was loaded onto a cattle car and taken to the concentration camp in Mauthausen. Your mother never discussed the Hungarian side of the family, instead selectively acknowledging the French lineage of her mother’s side. You found and communicated with the only other living member of the Engel de Jánosi family of your mother’s generation, Anna Stein. Recovering from your father’s death and healing from a new hip, your mother was willing to return to Europe in 2013. As your mother and Anna meet, you reflect that “Keeping secrets kept them alive, but that’s also how they lost contact with their families… They both know how to suffer and they both know how to worry… It’s the living they sometimes have trouble with.” After the visit with Anna Stein, you boarded a bus with your mother and she begins to cry, “Her weeping becomes guttural, the same sound she made the day my father died. Her slight shoulders shake and she puts her head into the crook of my arm. She is crying for everything and everyone – her dead husband, her father, her mother, her lost family and country. She is crying for herself and for all those in her family she knew and never knew.” And this Margaret, my dear friend, is what I have to tell you in this long letter – I won’t be able to review “Where the Angels Lived” if asked. It’s too close. It’s emotional – and yet, in the end filled with hope and love and leaves me with a sense of a future for humanity because of what you did. I cannot add words or commentary to something so beautifully lived and written. With much love, -Scott

“Where the Angels Lived: One Family’s Story of Exile, Loss, and Return”

By Margaret McMullan Calypso Editions ISBN: 9781944593087 $19.95

Books may be ordered (and shipped, if requested) here.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Shoofly Magazine Partners

Our Shoofly Partners are local businesses and organizations who share our mission to enrich community life in Bay St. Louis, Waveland, Diamondhead and Pass Christian. These are limited in number to maximize visibility. Email us now to become a Shoofly Partner!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed